Constitutional Right to Trial in Bankruptcy Discharge: The Japanese Supreme Court's 1991 Stance

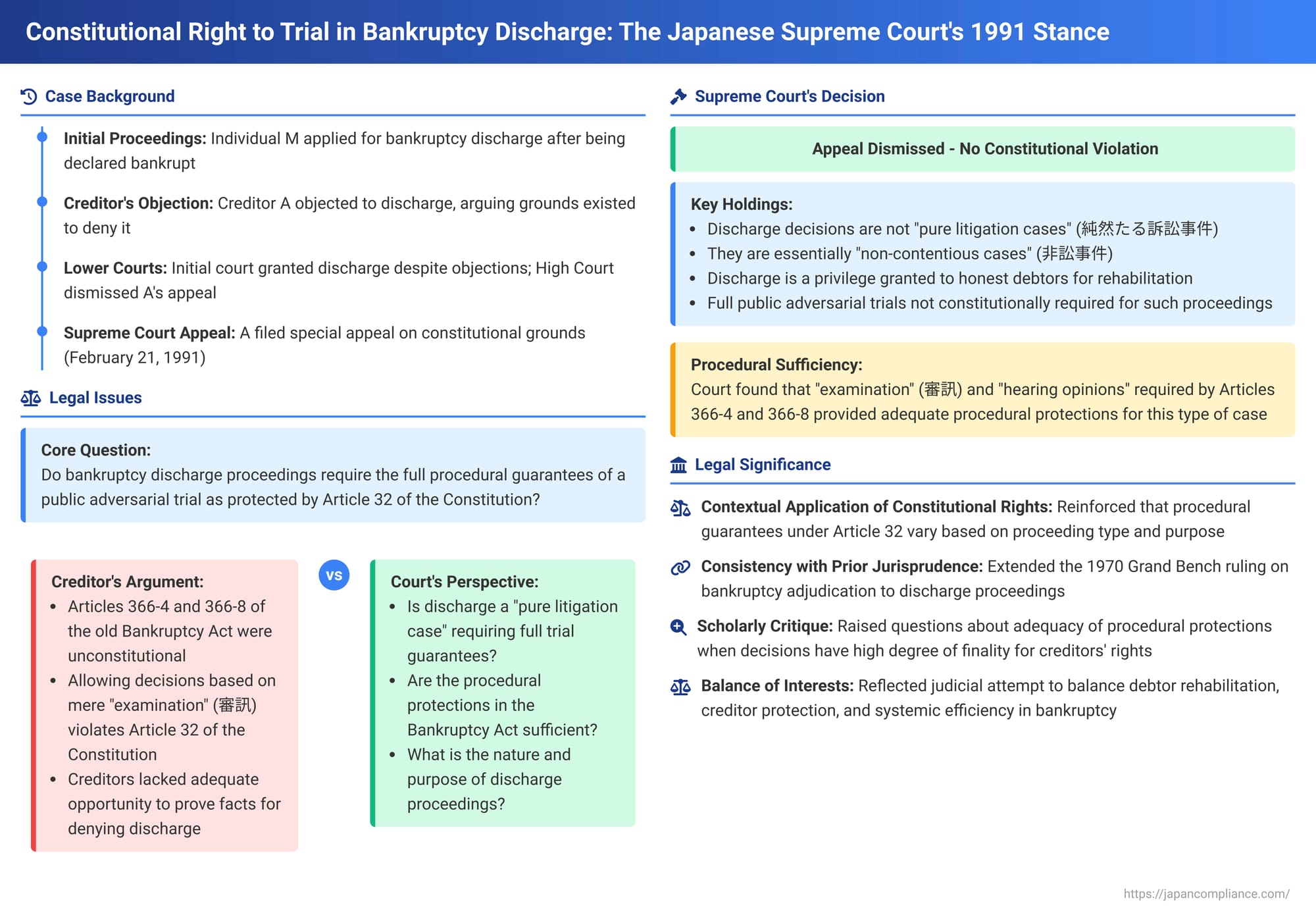

On February 21, 1991, the Third Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan issued a decision in a case concerning a creditor's challenge to a bankruptcy discharge order. This judgment further clarified the Court's position on the application of constitutional rights to a trial, particularly Article 32 of the Japanese Constitution, within the specialized framework of bankruptcy proceedings. Echoing earlier jurisprudence, the Court found that discharge decisions, due to their specific nature, do not necessitate the full procedural guarantees of a public, adversarial trial typically associated with "pure litigation cases."

Background of the Discharge Dispute

The case arose after an individual, M, who had been declared bankrupt, applied for a discharge from outstanding debts under the provisions of the (now-repealed) Bankruptcy Act. A, a creditor of M, formally objected to this discharge application, asserting that grounds existed which should disqualify M from receiving such a discharge. These grounds often relate to dishonest conduct by the debtor, such as fraudulent bankruptcy or dissipation of assets.

Despite A's objections, the initial court granted the discharge order to M. This order would effectively release M from the legal obligation to pay most remaining debts that were not satisfied through the distribution of the bankruptcy estate. A appealed this decision to the Tokyo High Court, reiterating the arguments that grounds for denying discharge were present. The High Court, in a decision dated December 19, 1989, dismissed A's appeal.

Persisting in the challenge, A filed a special appeal with the Supreme Court of Japan, bringing constitutional questions regarding the discharge process to the forefront.

The Creditor's Constitutional Challenge to the Discharge Process

In the special appeal, the appellant creditor, A, contended that certain provisions of the old Bankruptcy Act governing the discharge procedure were unconstitutional. Specifically, A targeted:

- Article 366-4 of the old Bankruptcy Act: This article allowed the bankruptcy court to make a discharge decision based on an "examination" (審訊 - shinjin) procedure. A shinjin is generally a less formal hearing process than a full oral argument in open court.

- Article 366-8 of the old Bankruptcy Act: This article stipulated that if an objection to discharge was filed (as A had done), the bankruptcy court was required to hear the opinions of the bankrupt debtor and the objecting creditor(s).

A argued that these provisions violated Article 32 of the Constitution of Japan, which guarantees the right to a trial (often interpreted as the right of access to courts and a fair hearing). The core of A's assertion was that these statutory procedures deprived creditors of an adequate opportunity to prove facts that would constitute grounds for denying discharge, such as allegations of fraudulent bankruptcy or culpable failure to preserve assets. A implied that the "examination" and "hearing of opinions" were insufficient substitutes for a more formal trial where evidence, including testimony, could be fully presented and contested.

Additionally, A raised a claim that Article 366-9 of the old Bankruptcy Act, which detailed the grounds for denying discharge, was in violation of Article 29 of the Constitution (guaranteeing property rights). However, the Supreme Court swiftly dismissed this part of the appeal. It noted that its own established precedent (specifically, a Grand Bench decision from December 13, 1961) had already determined that the statutory provisions for bankruptcy discharge do not contravene Article 29. Thus, this particular argument was deemed to be without merit. The main focus of the Court's decision, therefore, was on the Article 32 challenge.

The Supreme Court's Reasoning on Discharge Orders and Article 32

The Supreme Court ultimately dismissed A's appeal, finding no violation of Article 32. Its reasoning was multifaceted, centering on the unique nature and purpose of the bankruptcy discharge system.

- Purpose of the Discharge System:

The Court began by reiterating the fundamental objective of the bankruptcy discharge system under the (then-operative) Bankruptcy Act. It described discharge as a privilege granted to honest bankrupt debtors. The system's aim is to release such debtors from the legal responsibility for debts that could not be satisfied from the bankruptcy estate (with certain exceptions for non-dischargeable debts, like some taxes or damages from torts committed with malicious intent). This release is intended to facilitate the debtor's economic rehabilitation and fresh start. This perspective frames discharge not as an absolute right of the debtor or a simple adjudication of existing claims, but as a specific statutory measure with a socio-economic goal. - Reaffirmation of the "Pure Litigation Case" Doctrine:

Central to the Court's decision was its reliance on the established constitutional doctrine distinguishing different types of judicial proceedings. The Court stated that a discharge decision is not a "pure litigation case" (純然たる訴訟事件 - junzen taru soshō jiken). As established in prior jurisprudence (including the landmark 1970 Grand Bench decision concerning bankruptcy adjudication), "pure litigation cases" are those judicial proceedings whose primary purpose is the definitive determination of substantive rights and obligations between contending parties. Such cases, according to the Supreme Court, are the ones to which the full procedural guarantees of Article 82 (public trial) and, by extension, the robust aspects of Article 32, most directly apply. - Characterization as "Non-Contentious":

Building on this, the Court explicitly characterized the nature of a discharge decision as being essentially that of a "non-contentious case" (非訟事件 - hishō jiken). Non-contentious matters in Japanese law generally involve judicial intervention or supervision in situations that are not primarily adversarial disputes over legal rights in the same way as typical lawsuits. Instead, they often concern the creation or alteration of legal statuses, the administration of affairs, or the granting of specific statutory benefits or reliefs, where the court exercises a degree of discretion and a more inquisitorial role. Examples often come from family law (e.g., appointments of guardians) or corporate matters. By classifying discharge decisions this way, the Court signaled that the procedural requirements could legitimately differ from those applicable to standard civil litigation. - No Violation of Article 32:

Given this characterization, the Court concluded that the fact that discharge decisions could be made without a full, public, adversarial hearing (公開の法廷における対審 - kōkai no hōtei ni okeru taishin) in open court did not mean that Articles 366-4 and 366-8 of the old Bankruptcy Act violated Article 32 of the Constitution. The procedural safeguards inherent in the concept of a "trial" under Article 32, when applied to non-contentious matters, do not necessarily mandate the same level of formality or adversarial structure as in pure litigation. - Reliance on Precedent:

The Supreme Court explicitly stated that this conclusion was clear in light of its existing body of precedent. It specifically cited several earlier decisions, including the pivotal Grand Bench decision of June 24, 1970 (Showa 41 (Ku) No. 402). That 1970 case had established that even the initial bankruptcy adjudication order was not a "trial" in the Article 82 sense, and therefore did not constitutionally require a public oral hearing for its issuance. The 1991 Court found the reasoning in those precedents applicable to discharge decisions as well.

The remainder of A's arguments in the appeal were dismissed by the Court as being, in substance, mere allegations of ordinary statutory violations or errors by the lower court, rather than qualifying as grounds for a special appeal on constitutional issues.

Procedural Guarantees in Discharge Proceedings: A Closer Look

While the Supreme Court found the discharge process constitutionally adequate, legal commentary has explored the implications of not guaranteeing full oral arguments for decisions that significantly impact creditors. A discharge order, by releasing a debtor from most debts, directly affects the financial interests of creditors who may see their claims become largely unenforceable.

The old Bankruptcy Act, under Article 366-8, did provide some procedural involvement for creditors. It mandated that if a creditor filed an objection to the discharge application, the bankruptcy court was required to hear the opinions of both the bankrupt debtor and the objecting creditor. Furthermore, Article 366-4 referred to an "examination" (shinjin) procedure. Legal practice under the old law indicated that such shinjin hearings were flexible and their specific format was largely left to the court's discretion; they could even be conducted based on written submissions without a formal court session. This means that while parties' views were considered, the process lacked the guarantees of publicity, direct confrontation, and oral presentation inherent in a formal oral argument (口頭弁論 - kōtō benron).

The Supreme Court's 1991 decision implies that these procedures—the court's examination and the hearing of opinions when objections are raised—were deemed constitutionally sufficient for a matter classified as "non-contentious." The reasoning aligns with a broader judicial approach where the level of procedural formality is tailored to the nature of the judicial act.

However, a point of critique highlighted in legal analysis concerns the underlying justification often used by the Supreme Court for not extending full trial rights to non-contentious matters. This justification is that parties typically retain the opportunity to have their substantive rights definitively determined in a separate "pure litigation case". For instance, in the 1970 bankruptcy adjudication case, the Court noted that the existence of a debt itself could be conclusively litigated in a claim determination lawsuit.

Legal scholars have questioned whether this rationale seamlessly applies to discharge decisions. If a discharge is granted, and a creditor's claim is thereby declared discharged, it becomes difficult for that creditor to subsequently initiate a lawsuit to meaningfully establish the existence or enforceability of that debt. The discharge order itself would likely lead to the dismissal of such a suit or a judgment that the debt is no longer legally enforceable (perhaps subsisting only as a "natural obligation" without legal teeth, depending on the prevailing theory of discharge's effect). This suggests that the discharge decision itself has a more final impact on the creditor's substantive rights than some other "non-contentious" decisions, raising questions about whether the procedural safeguards within the discharge process itself are robust enough. If the primary opportunity to contest the debtor's eligibility for discharge (and thus preserve the claim's enforceability) lies within the discharge proceeding, and that proceeding lacks full trial guarantees, a potential tension arises.

Distinction from Bankruptcy Adjudication but Similar Constitutional Rationale

This 1991 Supreme Court decision on discharge orders shares a fundamental constitutional rationale with the earlier 1970 Grand Bench decision on bankruptcy adjudication orders, despite addressing different stages of the bankruptcy process. The 1970 case dealt with the initiation of bankruptcy proceedings, while the 1991 case concerned the conclusion of the process for an individual debtor via discharge.

In both instances, the Supreme Court prioritized the specific nature and objectives of the bankruptcy system when interpreting constitutional procedural rights. For bankruptcy adjudication, the Court emphasized its role in initiating a collective procedure for asset administration and distribution. For discharge, the Court highlighted its character as a privilege for honest debtors aimed at rehabilitation. Both decisions concluded that these judicial acts are not "pure litigation cases" designed for the definitive settlement of bilateral substantive rights disputes, and thus do not constitutionally mandate a public, adversarial oral hearing as a prerequisite for their validity.

This approach allows for more streamlined and potentially quicker judicial action in these specialized areas, which involve multiple interests and distinct policy goals compared to ordinary civil litigation.

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court's February 21, 1991, decision reinforces the classification of bankruptcy discharge proceedings as "non-contentious" matters, thereby placing them outside the scope of judicial acts that constitutionally require full, public, adversarial trials under Article 32 of the Japanese Constitution. This classification implies that fewer procedural guarantees are mandated compared to "pure litigation cases," reflecting a balance between the debtor's interest in rehabilitation, the creditors' rights to their claims, and the overall efficiency of the bankruptcy system.

The judgment rests on the premise that the procedural opportunities available within the discharge framework under the old Bankruptcy Act—such as the court's examination and the requirement to hear opinions from objectors—were sufficient to meet the constitutional threshold for this type of judicial decision. It underscores a consistent theme in Japanese constitutional jurisprudence: the interpretation of rights like the "right to a trial" is often contextual, varying with the nature and purpose of the specific legal proceeding in question. While this provides flexibility, it also invites ongoing discussion, particularly from the perspective of affected parties like creditors, regarding the adequacy of procedural safeguards when significant financial interests are at stake and the decision itself has a high degree of finality regarding those interests.