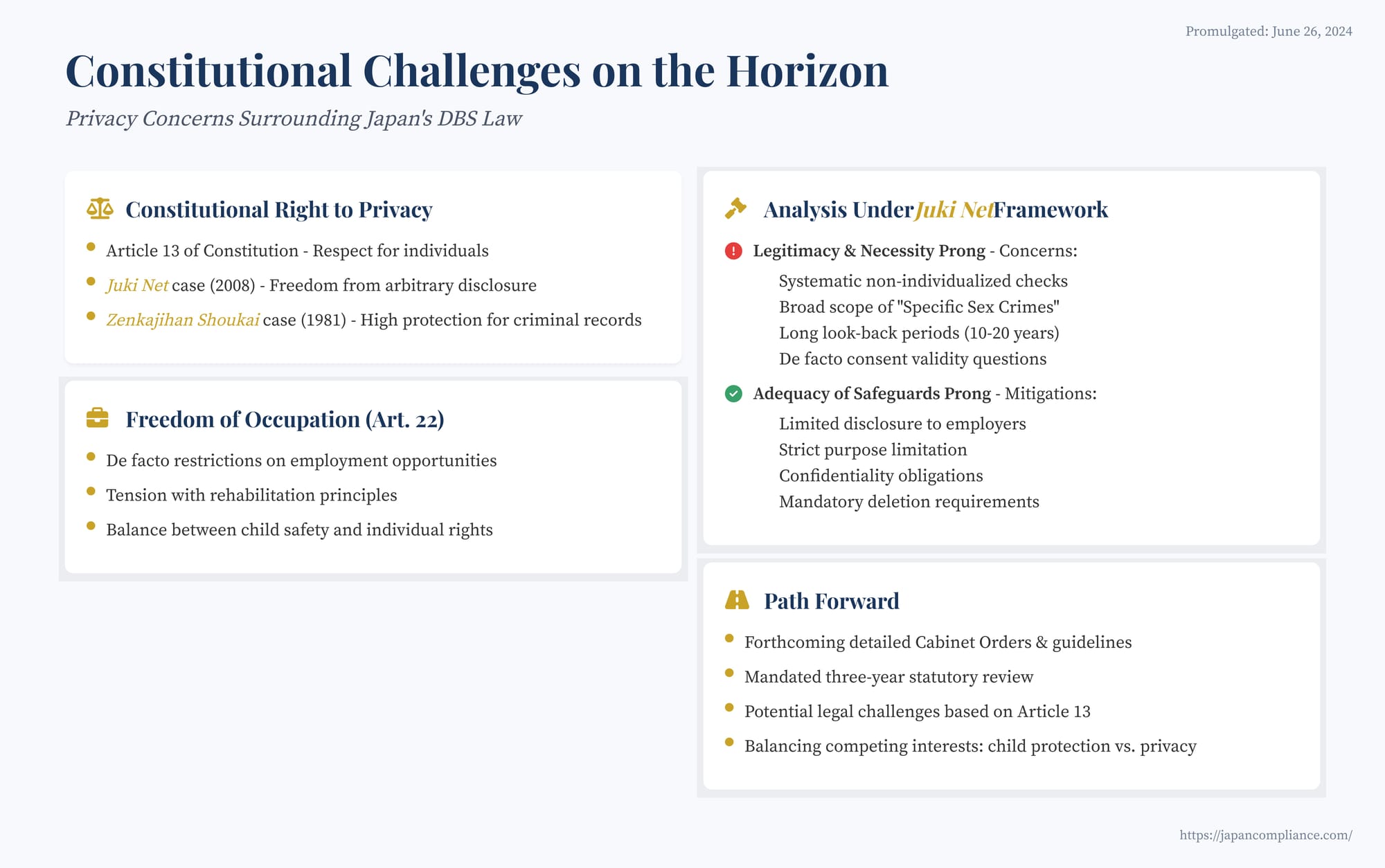

Constitutional Challenges on the Horizon? Privacy Concerns Surrounding Japan's DBS Law

TL;DR: Critics say Japan’s DBS Law risks over-collection and indefinite storage of criminal records, potentially violating Article 13 privacy rights. Constitutional challenges will likely hinge on proportionality, purpose limitation, and due-process safeguards. Businesses should prepare for stricter data-handling obligations and possible injunction scenarios.

Table of Contents

- Introduction: Balancing Child Safety and Privacy

- Japan’s Constitutional Privacy Framework

- Proportionality Analysis: Is the DBS Law Too Broad?

- Due-Process Concerns and Remedies

- Business Implications and Risk Mitigation

- Conclusion

Introduction

Japan's enactment of the "Act on Measures for the Prevention, etc. of Child Sexual Abuse by School Establishments, etc. and Private Education/Childcare Providers, etc." (Act No. 69 of 2024), commonly known as the "Japanese DBS Law," marks a significant step towards bolstering child safety in educational and childcare environments. By establishing a system for checking specific criminal records of individuals working with children, the law aims to prevent potential abuse by those in positions of trust. The objective is undeniably crucial and commands broad societal support.

However, like similar systems implemented internationally, the Japanese DBS Law inevitably operates in tension with fundamental rights, most notably the constitutional right to privacy. The systematic collection, governmental checking, and disclosure to employers of sensitive criminal history information, even for the laudable goal of child protection, raises profound questions under Japanese constitutional law.

This article explores the constitutional dimensions of the Japanese DBS Law, focusing primarily on the right to privacy guaranteed under Article 13 of the Constitution of Japan. It examines the law's mechanisms through the lens of key Supreme Court precedents on informational privacy and assesses the potential challenges and ongoing debates surrounding the balance between safeguarding children and protecting individual rights.

1. The Constitutional Right to Privacy in Japan

While Japan's Constitution does not explicitly enumerate a "right to privacy," the Supreme Court of Japan has firmly established its existence as deriving from Article 13, which states: "All of the people shall be respected as individuals. Their right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness shall, to the extent that it does not interfere with the public welfare, be the supreme consideration in legislation and in other governmental affairs."

- Informational Privacy: A key component of this judicially recognized right is informational privacy – the freedom of individuals regarding the handling of their personal information. A landmark Supreme Court decision concerning the Juki Net (Basic Resident Register Network) system (Judgment of March 6, 2008) articulated this as including the "freedom not to have private information arbitrarily disclosed to third parties."

- Sensitivity of Criminal Records: The Supreme Court has shown particular sensitivity towards the privacy of criminal records. In the Zenkajihan Shoukai Jiken (Prior Criminal Record Inquiry Case) (Judgment of April 14, 1981), the Court recognized that prior criminal history is a matter directly concerning a person's honor and reputation. It held that individuals possess a legally protected interest against the arbitrary disclosure of such information. The Court ruled that disclosure by public authorities (in that case, a municipality responding to a lawyer's inquiry) is permissible only under very limited circumstances, such as when the existence of a prior conviction is a crucial point of contention in litigation and there is no other method to prove it. This precedent established a high bar for justifying the disclosure of criminal records.

The Japanese DBS Law, which mandates the checking and potential disclosure (albeit in limited form) of specific sex crime convictions to employers, must be evaluated against this constitutional backdrop, particularly the high degree of protection afforded to sensitive criminal history information.

2. Analyzing the DBS Law under the Juki Net Framework

The Juki Net case provides a useful two-pronged framework for assessing the constitutionality of state systems handling personal information:

- Legitimacy and Necessity: Is the collection, use, and disclosure of the information based on a clear legal foundation and undertaken for a legitimate public purpose? Is the intrusion into privacy necessary and proportionate to achieve that purpose?

- Adequacy of Safeguards: Are there sufficient legal and technical safeguards in place to prevent unauthorized access, disclosure, or misuse of the information beyond the stated purpose?

Applying this framework to the Japanese DBS Law reveals several points of tension:

2.1. Prong 1: Legitimate Purpose, Necessity, and Proportionality

- Legitimate Purpose: The goal of protecting children from sexual abuse is undoubtedly a legitimate and compelling state interest, satisfying the initial part of this prong. The law itself provides the legal basis for the checks.

- Necessity and Proportionality – The Core Challenge: The more difficult questions lie here. Critics argue the system may be disproportionate and over-inclusive in its approach:

- Systematic, Non-Individualized Checks: The law mandates checks for all designated personnel (new hires and, periodically, existing staff) in covered institutions, without requiring any individualized suspicion or risk assessment beforehand. This contrasts sharply with the Zenkajihan Shoukai principle of disclosure only in specific, necessary circumstances. Is such broad, preventative screening necessary, or could less intrusive measures (enhanced supervision, robust reporting channels, checks based on specific concerns) achieve comparable protection?

- Scope of "Specific Sex Crimes" and Look-back Periods: The law defines a list of "Specific Sex Crimes" and sets lengthy look-back periods (up to 20 years post-sentence for custodial sentences, 10 years for fines or suspended sentences). Concerns exist about whether all included offenses, particularly some potentially covered by broad prefectural ordinances, and these fixed, long durations accurately reflect the specific risk of future sexual abuse against children in an educational/childcare setting. This approach can be seen as a form of "crude profiling" based on conviction type and time elapsed, rather than individualized risk. The expert committee report acknowledged the difficulty in establishing direct correlations for all included offense types and age groups but ultimately recommended a broad scope. Constitutional analysis asks whether this breadth is narrowly tailored to the specific risk being addressed.

- Over-Inclusiveness vs. Under-Inclusiveness: While the system is potentially over-inclusive by capturing individuals whose past offense bears little relation to current risk, it's also under-inclusive as it misses first-time offenders, those not convicted, or those with foreign convictions. While under-inclusiveness doesn't automatically make a law unconstitutional, significant over-inclusiveness raises proportionality concerns.

- The "De Facto Consent" Argument: The law requires employee cooperation (providing documents) for the check (Art. 33). This can be framed as obtaining a form of consent, potentially distinguishing it from the non-consensual disclosure addressed in Zenkajihan Shoukai. However, constitutional scholars question the voluntariness of this "consent," given that refusal likely means losing or being denied employment in a chosen field. It resembles the situation with existing checks for public servant disqualifications, the constitutionality of which has also been debated due to the pressure on applicants to "consent."

2.2. Prong 2: Adequacy of Safeguards

Recognizing the sensitivity of the data, the DBS Law incorporates several safeguards intended to meet the second prong of the Juki Net test:

- Limited Disclosure: The information passed from the government (CFA) to the employer is strictly limited. It confirms only whether the individual falls within the defined category ("Person Corresponding to Specific Sex Crime Facts") and, if so, provides only the broad category of the offense and the date the conviction became final. Crucially, details of the crime, victim information, or specific circumstances are not disclosed to the employer (Art. 35, Para. 4).

- Purpose Limitation: Employers are legally bound to use the information solely for assessing risk and implementing necessary preventive measures under the DBS Law (Art. 12). Use for other purposes (e.g., general performance evaluation, unrelated background checks) is prohibited.

- Confidentiality and Data Security: Strict confidentiality obligations are imposed on employers and their staff handling the information (Art. 39). Employers must implement necessary measures for secure data management (Art. 11, 14) and face penalties for breaches, including unauthorized disclosure (Art. 45, 46).

- Data Deletion: Employers must delete the Confirmation Document and related records after a specified period (typically 5 years post-check or earlier if employment ends/doesn't commence) to prevent indefinite retention of sensitive data (Art. 38).

- Employee Rights: Individuals have the right to be notified before adverse information is sent to the employer and the right to seek correction of inaccuracies (Art. 35, 37).

- Regulatory Oversight: The CFA has powers to request reports, conduct inspections, and issue orders to ensure employer compliance with data management rules (Art. 16-18).

Evaluation of Safeguards:

These measures represent a significant effort to mitigate privacy risks. Limiting the information flow to the employer is particularly important. However, concerns remain:

- Risk of Leaks/Misuse: Despite legal obligations and penalties, the risk of accidental leaks or intentional misuse of even limited information by employers or individual staff members cannot be entirely eliminated. The potential for stigma associated with any "positive" check result is high.

- Effectiveness of Oversight: The practical effectiveness of CFA oversight, especially given the potentially large number of employers involved (including many smaller private providers who may opt for certification), is crucial but yet to be fully tested. Coordination with the Personal Information Protection Commission (PPC), Japan's primary data protection authority, will also be important, particularly regarding potential delegation of oversight powers (as discussed in the context of the APPI).

- Sufficiency Given Data Sensitivity: Compared to the Juki Net or My Number cases (which involved less inherently sensitive identification data), the DBS law handles extremely sensitive criminal history. Arguably, the required safeguards need to be correspondingly robust. Whether the current measures meet this heightened standard may be subject to future scrutiny.

3. Freedom of Occupation and Other Considerations

While privacy (Art. 13) is the primary constitutional concern, other rights are implicated:

- Freedom of Occupation (Art. 22): Although the law doesn't create automatic disqualification, the practical reality is that a positive DBS check result, leading to an employer determining a "risk" under Article 6, will very likely prevent an individual from being hired for, or require their removal from, child-facing roles. This constitutes a significant de facto restriction on occupational freedom for individuals with relevant past convictions, even very old ones. The justification rests on the compelling interest of child safety within these specific job contexts.

- Principle of Rehabilitation: Criminal justice systems generally incorporate principles aiming at the rehabilitation and social reintegration of offenders after they have served their sentences. Long look-back periods under the DBS law (up to 20 years post-sentence completion) potentially conflict with these principles by continuing to impose significant employment restrictions long after legal punishment has ended. Balancing public safety concerns specific to child protection against the societal goal of reintegration is a difficult policy challenge embedded within the law's structure.

4. The Path Forward: Implementation, Review, and Potential Challenges

As the Japanese DBS Law moves into its implementation phase (likely having recently commenced as of May 2025), several factors will shape its constitutional trajectory:

- Detailed Regulations: The precise scope of "Specific Sex Crimes" covered by prefectural ordinances and the exact criteria for employer risk assessments under Article 6 will be detailed in forthcoming Cabinet Orders and potentially administrative guidelines. These details will be critical in determining the law's actual breadth and impact on privacy.

- Statutory Review: The law mandates a governmental review within three years of its enforcement commencement date (Art. 6, Supplementary Provisions). This review offers a vital opportunity to evaluate the system's effectiveness, necessity, proportionality, and impact on individual rights based on operational data and experience. Adjustments to the scope of crimes, look-back periods, or procedures could result from this review.

- Potential Legal Challenges: It is conceivable that the law, or specific applications of it, could face constitutional challenges in the courts. Potential plaintiffs might include individuals denied employment or reassigned based on dated convictions, arguing violations of privacy (Art. 13) or occupational freedom (Art. 22). Courts would then need to undertake the difficult balancing act between the state's compelling interest in child protection and the fundamental rights of individuals, applying frameworks established in cases like Juki Net and Zenkajihan Shoukai to this specific context. The outcome of any such challenges is uncertain but would significantly shape the law's future.

Conclusion

The Japanese DBS Law represents a major legislative initiative driven by the urgent need to protect children from sexual abuse in educational and childcare settings. However, its mechanism—involving the systematic checking and disclosure of sensitive criminal history—places it squarely in tension with Japan's constitutionally protected right to privacy and potentially impacts occupational freedom and rehabilitation principles.

While the law incorporates safeguards, including limiting the information disclosed to employers and imposing data management duties, significant constitutional questions remain regarding its necessity and proportionality. Is the broad, non-individualized screening approach sufficiently tailored to the specific risk? Are the scope of covered offenses and the lengthy look-back periods justifiable intrusions into privacy? Is the "de facto consent" obtained from employees truly voluntary?

As the law is implemented and operational data becomes available, these questions will likely intensify. The mandated three-year review offers a formal mechanism for reassessment. Ultimately, the long-term viability and acceptance of Japan's DBS system may depend on its perceived effectiveness in preventing abuse, the robustness of its privacy safeguards in practice, and potentially, the outcomes of future constitutional scrutiny by the courts. For businesses operating under this law, meticulous compliance with data protection rules and fair application of risk assessment procedures are essential not only for legal adherence but also for navigating the complex ethical and constitutional dimensions involved.

- Japan’s New DBS Law: Protecting Children in Educational and Childcare Settings

- Navigating DBS Checks and Employment Law in Child-Related Businesses

- Data Privacy in the Age of DX: Japan’s Approach to Utilization and Protection

- Children and Families Agency — DBS Law Privacy FAQ (JP)

https://www.cfa.go.jp/policies/dbs_privacy_faq.html