Consent or Coercion? Japanese Supreme Court Sets High Bar for Agreeing to Worse Work Rules

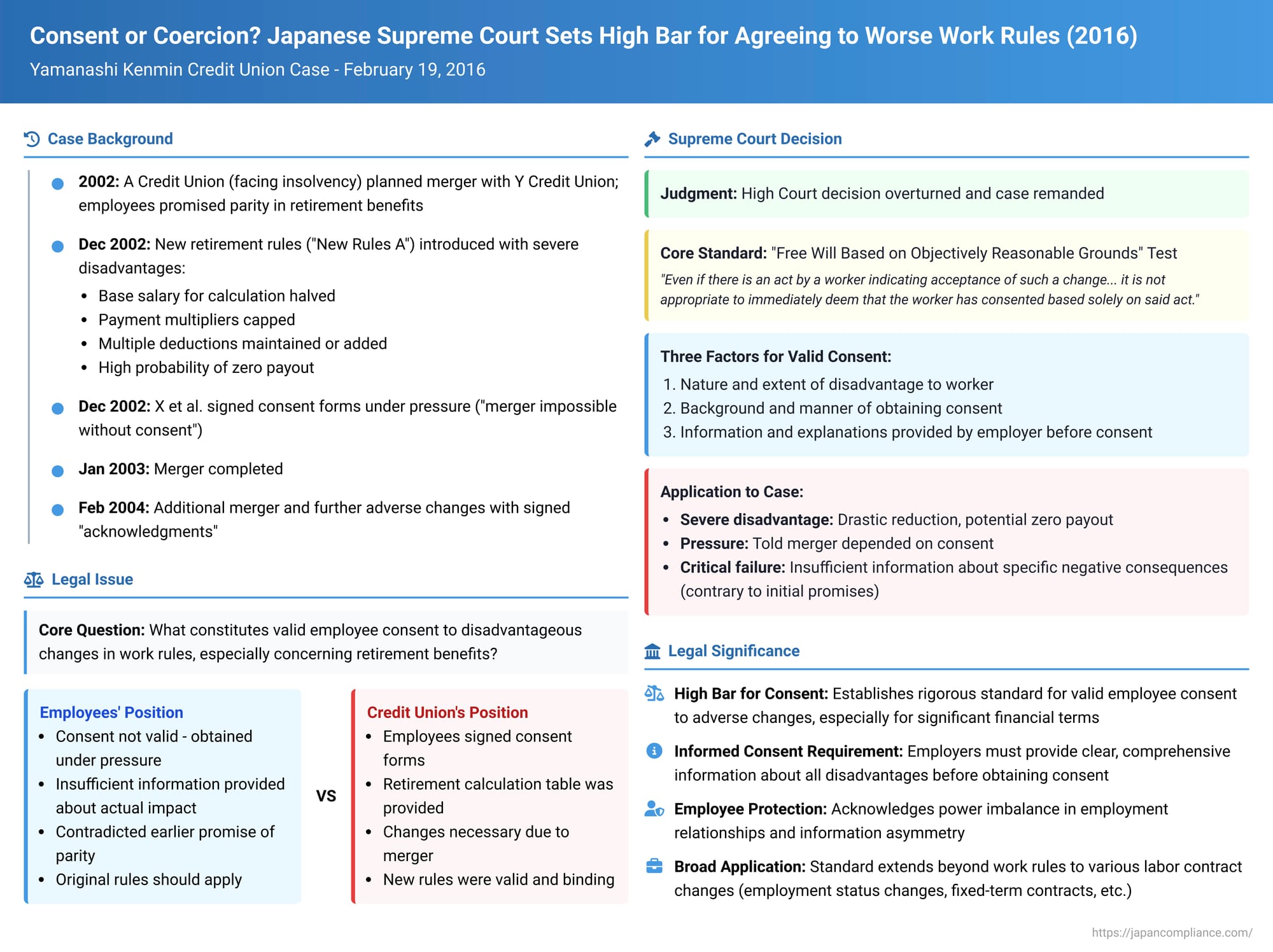

When employers seek to change work rules, especially in ways that are disadvantageous to employees, Japanese labor law provides two main pathways for such changes to become binding. First, an employer can unilaterally implement changes if they are deemed "reasonable," even if individual employees do not consent (a principle codified in Article 10 of the Labor Contract Act, stemming from earlier case law like the Shuhoku Bus case). Second, changes can be made through individual agreement with employees (as per Articles 8 and 9 of the Labor Contract Act). The Supreme Court of Japan's decision in the Yamanashi Kenmin Shinyo Kumiai (Credit Union) case on February 19, 2016, provided crucial clarification on the latter, establishing a high standard for what constitutes valid employee consent, particularly when financially significant terms like retirement benefits are adversely affected.

The Yamanashi Kenmin Saga: Mergers and Drastically Reduced Retirement Pay

The plaintiffs, X et al., were former employees of A Credit Union. Faced with potential insolvency, A Credit Union arranged to merge with Y Credit Union, with Y agreeing to take on A's existing staff. It was also agreed that for calculating retirement benefits, the employees' total years of service with both A and Y would be counted.

In November 2002, a draft consent form prepared for A's employees indicated that their retirement benefits post-merger would be guaranteed at the same level as Y Credit Union's original employees. However, this point was later contested by Y, and further internal discussions ensued.

Subsequently, new retirement benefit rules (referred to as "New Rules A") were drafted to replace A Credit Union's existing "Old Rules." These "New Rules A" introduced severe modifications, termed "The Current Standards Change":

- The basic salary used for calculating retirement benefits was halved compared to the Old Rules.

- A cap was introduced on the支給倍数 (shikyū baisū - payment multiplier, based on years of service and reason for retirement), which had not existed under the Old Rules.

- The Old Rules featured an "internal deduction method" (内枠方式 - uchiwaku hōshiki), where the amount of benefits receivable by employees from the national credit union welfare pension fund was deducted from their gross company retirement payout. Despite Y Credit Union's own employees not being subject to such a method, "New Rules A" maintained this internal deduction for former A employees.

- Furthermore, any refunds received by employees from A Credit Union's corporate pension plan (which was to be dissolved due to the merger) would also be deducted from their retirement payout.

The cumulative effect of these changes was a drastic reduction in the retirement benefits for A's former employees, with a high probability that the actual amount paid out would be zero. This also created a significant disparity compared to the retirement benefit standards for Y's original employees, contrary to the impression given by the November 2002 draft consent form.

The process of obtaining consent for "The Current Standards Change" was also contentious. In a December 2002 staff meeting at A Credit Union, the managing director distributed the November 2002 draft consent form (which implied parity with Y's staff) while explaining the calculation method based on the significantly less favorable "New Rules A". Later, A's executives presented a formal consent document ("the Current Consent Form"), reflecting these harsh new terms, to managerial staff (including X et al.). They were told that signing was essential for the merger to proceed. All managerial employees signed this document.

The merger took effect in January 2003. In February 2004, Y Credit Union merged with three more local credit unions ("2004 Merger"). Prior to this, new working condition instructions were issued. These included the "2004 Standards Change" for retirement benefits, stipulating that for pre-2004 merger service, if retirement calculation coefficients varied by reason for retirement (e.g., company-都合 vs. voluntary), the less favorable "voluntary retirement" coefficient would be used. It also stated that for post-2004 merger service, employees retiring voluntarily before a new comprehensive retirement system was established (planned within three years) would receive no retirement pay for that specific period of service. X et al. signed a document acknowledging and agreeing to these (and other) working condition changes detailed in an explanatory document.

In April 2009, Y implemented a new comprehensive retirement system ("2009 Rules"). For X et al., the application of "The Current Standards Change" and the "2004 Standards Change" to their pre-2004 merger service period resulted in their calculated retirement benefits being zero, as the deductions (welfare pension, corporate pension refund) exceeded the drastically reduced gross amount. Those among X et al. who retired voluntarily before the 2009 Rules were implemented also received no retirement pay for their service after the 2004 merger, per the "2004 Standards Change".

X et al. sued Y Credit Union, demanding retirement benefits based on the terms of the original A Credit Union "Old Rules." The lower courts ruled in favor of Y, finding that X et al. had validly consented to both sets of changes. X et al. appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's 2016 Ruling: Scrutinizing "Consent"

The Supreme Court, in its judgment on February 19, 2016, overturned the High Court's decision and remanded the case for further consideration, focusing on the validity of the employees' consent.

The Court first reaffirmed the general principle that working conditions, which form the content of a labor contract, can be altered by individual agreement between the worker and the employer. This principle holds true even when the working conditions being unfavorably changed are stipulated in work rules (the Court referenced Articles 8 and 9 of the Labor Contract Act in this context). However, the Court noted that if such an agreement necessitates a change to the work rules themselves (to avoid conflict with the work rules' minimum standards effect), then the work rules must indeed be amended.

The Core Principle: Heightened Scrutiny for Consent to Adverse Financial Changes

The Supreme Court then articulated a critical standard for assessing consent when the changes involve significant financial terms like wages or retirement benefits:

"Even if there is an act by a worker indicating acceptance of such a change, considering that the worker is employed by the employer and is in a position to be subject to its direction and orders, and that the worker's ability to collect information that forms the basis of their own decision-making is also limited, it is not appropriate to immediately deem that the worker has consented based solely on said act. The determination of whether or not the worker has consented to said change should be made cautiously."

The "Free Will Based on Objectively Reasonable Grounds" Test

Building on this cautionary note, the Court established a specific test:

The validity of an employee's consent to adverse changes in wage or retirement benefit conditions set by work rules should be judged not only by the presence of an act indicating acceptance but also from the perspective of "whether objectively reasonable grounds exist to recognize that the said act was based on the worker's free will."

This determination requires comprehensive consideration of:

- The nature and extent of the disadvantage brought upon the worker by the change.

- The background and manner in which the worker came to perform the act of acceptance.

- The content of information provided or explanations given to the worker by the employer prior to the act.

The Court cited its past rulings in cases like Singer Sewing Machine (waiver of wage claims) and Nisshin Steel (consent to wage set-offs) where similar "free will" based on objective reasonable grounds frameworks were employed.

Application to X et al.'s "Consent" to "The Current Standards Change":

Applying this rigorous test to the facts concerning "The Current Standards Change," the Supreme Court found the High Court's assessment of consent to be flawed:

- Severity of Disadvantage: The change was profoundly disadvantageous. The new calculation method (halving base salary, capping multipliers, maintaining the "internal deduction method" unlike Y's own staff, and adding further deductions) made it highly probable that actual retirement payouts would be zero. This was also grossly imbalanced when compared to the retirement benefits for Y Credit Union's original employees and contradicted the impression from the earlier draft consent form that promised parity.

- Circumstances of Consent: The managerial employees, including X et al., were told by A Credit Union's executives that their consent was a prerequisite for the financially distressed A Credit Union to merge with Y, implying significant pressure.

- Insufficiency of Information: This was a critical failure. For X et al. to make a genuinely informed decision, simply explaining the need for changes to the Old Rules due to the merger was insufficient. They needed to be clearly and fully informed about the specific and severe negative consequences of "The Current Standards Change." This included the high likelihood of receiving no retirement pay under certain conditions (like voluntary retirement) and the significant disparity with Y's existing staff's benefits—details that contradicted the more favorable impression given by the initially circulated November 2002 draft. The High Court had found consent based on the employees signing the form and having seen a "Retirement Allowance Table" (本件退職金一覧表) prepared by management. However, this table was primarily for calculating the company's reserve liability for retirement benefits, assuming ordinary retirement, and did not necessarily provide a complete picture of all potential outcomes for individual employees, especially under different retirement scenarios or the full impact of all deductions.

The Supreme Court concluded that the High Court did not adequately consider these points—particularly the lack of sufficient information regarding the concrete disadvantages—before finding that X et al. had validly consented. The lower court's judgment was therefore deemed flawed due to insufficient deliberation and a misapplication of legal principles regarding consent. A similar critique was applied to the High Court's finding of consent regarding the "2004 Standards Change."

The Importance of Truly Informed Consent

The Yamanashi Kenmin Shinkumi ruling powerfully underscores that employee consent, especially when it involves accepting significant financial detriments through changes to work rules, cannot be a mere formality. The Supreme Court's emphasis on the quality, completeness, and accuracy of information provided by the employer before consent is given is paramount. It's not simply about whether an employee signed a document; it's about whether they had the necessary, clear, and unambiguous information to understand the full scope and consequences of what they were agreeing to, particularly the negative impacts.

Legal Context and Implications

This decision provides critical clarification within the framework of Japanese labor law concerning changes to work rules:

- Distinction from "Reasonableness" Test: While Article 10 of the LCA allows employers to unilaterally impose adverse work rule changes if those changes are "reasonable" (even without individual consent), the Yamanashi Kenmin case focuses on changes based on individual employee agreement under Article 9 of the LCA. This ruling clarifies that if an employer relies on individual consent for an adverse change, that consent itself must meet a high standard of validity.

- Reinforcing Precedent on "Free Will": The judgment aligns with a consistent line of Supreme Court cases that carefully scrutinize an employee's purported consent in situations involving disadvantages, such as waiving wage claims, agreeing to employer set-offs against wages, or consenting to demotions. The underlying principle is the protection of employees given their inherently subordinate position and potential information asymmetry in the employment relationship.

- Practical Impact for Employers: Employers seeking to implement adverse changes to financially significant work rules through individual employee consent must now be acutely aware of their obligations regarding information disclosure. They must:

- Provide clear, comprehensive, and accurate explanations of all potential disadvantages.

- Ensure employees understand the full implications, especially long-term financial impacts and comparisons with any prior or different terms.

- Avoid any impression of coercion or misrepresentation. Relying on signatures obtained under pressure or with incomplete or misleading information is legally perilous.

- Broader Application: The rigorous standard for assessing consent articulated in this case, focusing on free will informed by adequate explanation, is proving influential in lower court decisions concerning various other types of adverse employment changes, not limited to wages and retirement benefits, such as alterations to employment status or the introduction of non-renewal clauses in fixed-term contracts.

Conclusion

The Yamanashi Kenmin Shinyo Kumiai case is a landmark decision in Japanese labor law, establishing a high threshold for what constitutes valid employee consent to disadvantageous changes in work rules, particularly those with significant financial repercussions like retirement benefits. It emphasizes that such consent must be genuinely free and fully informed, stemming from a clear understanding of all material consequences, especially the negative ones. This ruling reinforces the protective stance of Japanese labor law, acknowledging the inherent power imbalance in the employment relationship and mandating that employee agreement to detrimental changes is not lightly presumed but rigorously examined. It serves as a critical reminder for employers of their duty to act transparently and ensure true voluntariness when seeking employee agreement to alter fundamental terms of employment.