Conflict, Promissory Notes, and Corporate Liability: A Japanese Supreme Court Landmark on Director Transactions

Case: Action for Payment on Promissory Notes

Supreme Court of Japan, Grand Bench, Judgment of October 13, 1971

Case Number: (O) No. 1464 of 1967

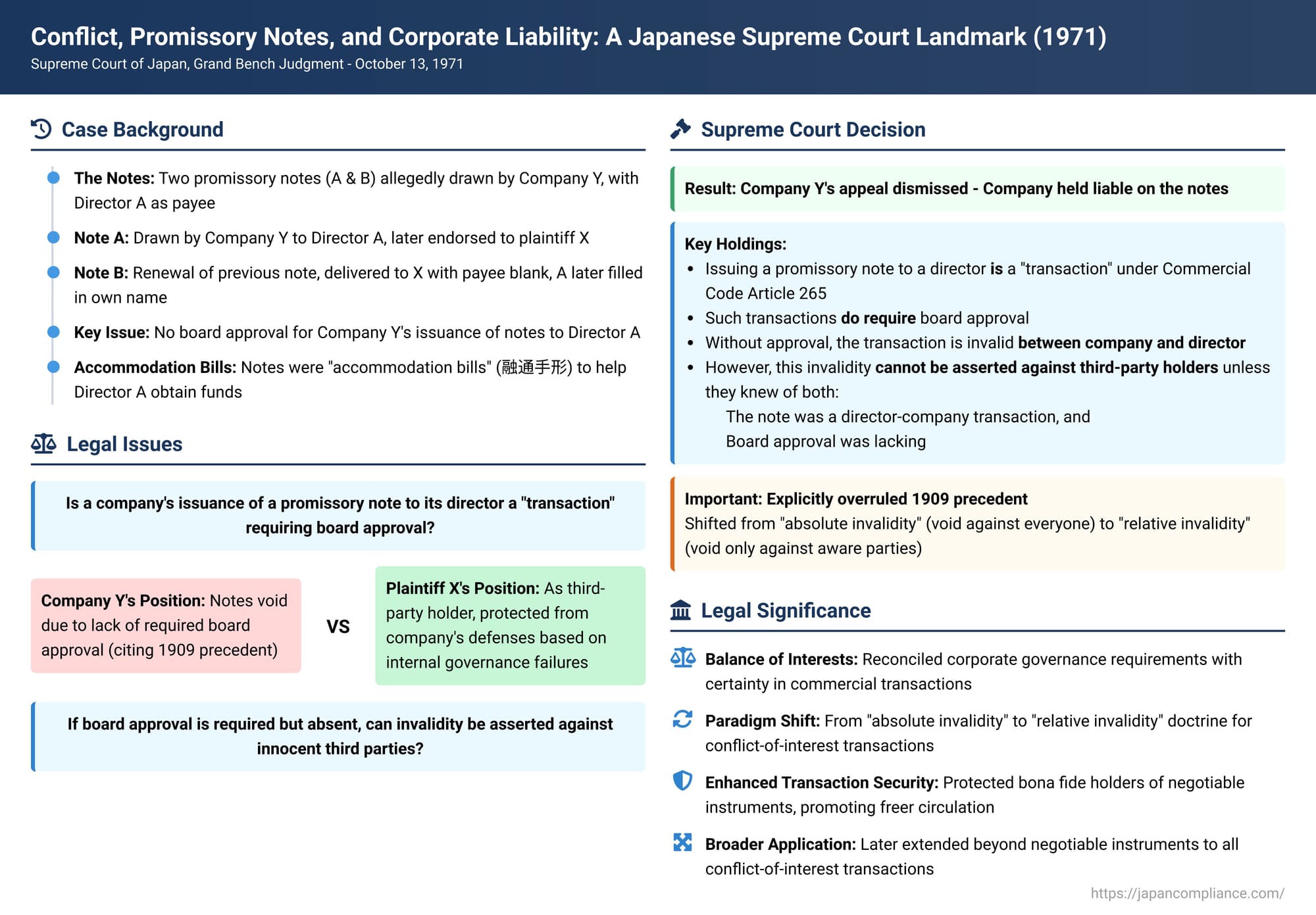

Transactions between a company and one of its own directors inherently carry the risk of a conflict of interest, where the director might prioritize personal benefit over the company's welfare. To mitigate this risk, Japanese company law has long mandated that such transactions receive approval from the company's board of directors. But what happens when this approval is missing, especially when the transaction involves a negotiable instrument like a promissory note that subsequently finds its way into the hands of a third party? A landmark Grand Bench decision by the Japanese Supreme Court on October 13, 1971, fundamentally reshaped the legal landscape in this area, balancing the need to protect companies from unauthorized director dealings with the imperative of ensuring safety and certainty in commercial transactions, particularly those involving negotiable instruments.

Accommodation Bills and Allegations of Invalidity: Facts of the Case

The plaintiff, X, was the holder of two promissory notes (referred to as Note (A) and Note (B)) allegedly drawn by Company Y. The circumstances surrounding these notes were:

- Director A: A key figure was A, a director of Company Y. The notes were essentially issued to help A secure financing.

- Promissory Note (A): Company Y had drawn this note making its director, A, the payee. A subsequently endorsed the note in blank (making it payable to bearer or any holder) and transferred it to X.

- Promissory Note (B): This note was a renewal of a previous promissory note that Company Y had also drawn payable to director A, which A had then delivered to X. For Note (B) itself, Company Y delivered it directly to X, with the payee's name left blank. X then had A write his (A's) name in the payee space and endorse the note.

- Lack of Board Approval: Critically, Company Y's board of directors had not given its approval for the issuance of Note (A), nor for the original note that Note (B) was intended to renew.

- Nature of the Notes: Both notes were the culmination of a series of renewals – between ten to twenty times – of what were essentially "accommodation bills" (融通手形 - yūzū tegata). These are notes drawn by one party (Company Y) to lend its credit to another party (director A), enabling A to obtain funds by discounting or negotiating the notes.

When X presented Note (A) and Note (B) for payment at their maturity, Company Y refused to honor them. Consequently, X filed a lawsuit against Company Y seeking payment of the amounts due on the notes. The Tokyo High Court had ruled in favor of X, prompting Company Y to appeal to the Supreme Court.

The Central Legal Questions Before the Grand Bench

The case presented two fundamental legal questions to the Supreme Court's Grand Bench (its highest deliberative body, convened for matters of significant legal importance or to overturn precedents):

- Does the act of a company drawing a promissory note payable to one of its own directors constitute a "transaction" within the meaning of the then-Commercial Code Article 265, thus requiring the approval of the company's board of directors? (Article 265 of the old Commercial Code is analogous to current Companies Act Article 356, Paragraph 1, Item 2 concerning direct transactions involving conflicts of interest, and Article 365, Paragraph 1 requiring board approval in board-managed companies).

- If such an act is a regulated conflict-of-interest transaction and the requisite board approval is absent, what is the legal status of the promissory note, particularly when it has been transferred to a third-party holder? Specifically, can the company assert the invalidity of the note against such a third party?

The Supreme Court's Grand Bench Pronouncement: A Shift in Doctrine

The Supreme Court Grand Bench dismissed Company Y's appeal, holding the company liable on the promissory notes. In doing so, it laid down crucial principles regarding conflict-of-interest transactions involving negotiable instruments.

Reasoning of the Apex Court: Reconciling Director Oversight with Commercial Certainty

The Court's reasoning addressed each of the central questions:

I. Issuing Promissory Notes to Directors is Generally a Regulated Conflict-of-Interest Transaction:

The Court affirmed that the act of a company drawing a promissory note payable to one of its directors "in principle, constitutes a transaction" under Commercial Code Article 265, thereby requiring board approval. Its rationale was:

- Promissory notes serve not only as a means to settle pre-existing debts from substantive transactions (like sales or loans) but are also widely used as a simple and effective method for granting and receiving credit.

- When a company issues a promissory note, it incurs a new and distinct legal obligation that is separate from any underlying causal transaction.

- This promissory note obligation is typically more stringent than an ordinary contractual debt. This is due to several features of negotiable instrument law, such as a shifted burden of proof in legal disputes, the "cutting off" of certain personal defenses that the drawer might have against the original payee when the note is transferred to a holder in due course, and the severe commercial consequences of dishonoring a note (e.g., suspension of bank transactions).

Given these factors, the Court concluded that such an act could potentially prejudice the company and benefit the director, thus falling within the ambit of transactions requiring board oversight.

II. The Effect of Lack of Board Approval on Third-Party Note Holders – Introducing "Relative Invalidity":

This was the most significant part of the judgment, where the Court explicitly overruled a long-standing precedent.

- The Court acknowledged the inherent nature of promissory notes: they are designed to circulate freely among many unspecified parties. This characteristic necessitates a high degree of protection for bona fide third parties to ensure the safety and reliability of commercial transactions involving such instruments.

- Based on this, the Court established the following rule for situations where a company issues a promissory note to one of its directors without the required board approval:

- Against the Director Payee: The company can assert the invalidity of the note's issuance against the director to whom the note was directly issued, citing the lack of board approval.

- Against a Third-Party Holder: However, once the note has been endorsed and transferred to a third party, the company cannot assert the invalidity of its issuance against that third party (and thus cannot evade its liability on the note) unless the company can prove two things:

- That the note was indeed drawn by the company payable to its director and that the requisite board approval for this issuance was lacking; AND

- That the third party was in "bad faith" (akui) concerning these facts. "Bad faith" in this context means that the third party knew both that the transaction was a director-company deal and that the necessary board approval had not been obtained. The burden of proving this bad faith on the part of the third party rests squarely on the company.

- Explicit Overruling of Precedent: In establishing this rule, the Supreme Court expressly overruled a much older Daishin-in (the Supreme Court of Japan before 1947) judgment from Meiji 42 (1909). That earlier precedent had held that promissory notes issued under such circumstances (company to director without board approval) were absolutely void, meaning they were invalid against everyone, including subsequent third-party holders, regardless of their good faith.

- Non-Applicability of Bills of Exchange Act Article 16(2) in This Specific Context: The Court clarified that its reasoning was not directly based on Article 16, Paragraph 2 of the Bills of Exchange Act (which generally protects a holder in due course from defenses that the drawer could assert against prior parties). The protection for the third party in this specific scenario (challenging the initial validity of the note due to internal corporate governance failures) flows from the Court's interpretation of the Commercial Code's conflict-of-interest provisions (Article 265) and the balance it strikes with transaction security.

III. Application to the Notes in Question:

- Promissory Note (A): X acquired this note from director A. The High Court had found that X was unaware of the lack of board approval for its issuance. Therefore, under the principles just laid out, Company Y could not assert the invalidity of its issuance against X and was liable.

- Promissory Note (B): The Court noted that Note (B) itself was delivered directly by Company Y to X (with A later filling in the payee details and endorsing). Thus, the issuance of Note (B) itself might not have been a transaction between Company Y and director A requiring approval. However, Note (B) was a renewal for a previous note. That previous note was issued by Company Y to director A without board approval. The High Court had found that X was unaware of the lack of board approval for that predecessor note when X acquired it. Since Company Y was liable to X on the predecessor note, it had no valid reason to refuse payment on Note (B), which was merely a renewal of that existing obligation.

The presence of several supplementary and dissenting opinions (from Justice Osumi, Justice Matsumoto, and a joint opinion by five other justices, plus one from Justice Irokawa) highlighted the complexity of the issues and the diverse legal reasoning even among the Grand Bench justices, particularly concerning the best theoretical pathway to the same result of protecting bona fide third parties.

Analysis and Implications: A New Era for Conflict-of-Interest Transactions

This 1971 Grand Bench decision was a watershed moment in Japanese corporate law, fundamentally altering the understanding of the consequences of unapproved conflict-of-interest transactions, especially in the realm of negotiable instruments.

- "Transaction" Broadly Construed for Promissory Notes: The Court's affirmation that issuing a promissory note to a director generally falls under the conflict-of-interest rules was significant. It rejected narrower views that might have treated such issuances merely as methods of payment for underlying debts (which themselves might or might not have been conflicts of interest) or argued that only the underlying substantive transaction, not the instrumental act of issuing the note, should be subject to board approval. The Court's emphasis on the new, stricter liability incurred by the company through a promissory note supported this broader interpretation. The "in principle" qualification in the judgment likely leaves room for exceptions where the note issuance genuinely poses no new risk or detriment to the company (e.g., if the director provides full cash consideration to the company at the moment the note is issued in their favor).

- The Landmark Shift from "Absolute Invalidity" to "Relative Invalidity":

The most profound impact of the judgment was its explicit overruling of the 1909 precedent and its adoption of a "relative invalidity" doctrine. Under the old "absolute invalidity" rule, a note issued by a company to its director without board approval was considered void from its inception, unenforceable by anyone. This posed a severe risk to anyone who subsequently acquired such a note, as they could unknowingly be holding a worthless piece of paper. This significantly undermined the reliability and free circulation of promissory notes if a company director was involved in the chain of title.

The "relative invalidity" approach adopted by the 1971 Grand Bench holds that while the transaction (and the note) is invalid as between the company and the self-dealing director, it is not automatically invalid against a third party who subsequently acquires the note in good faith. This dramatically enhanced the security of commercial transactions involving such instruments. - Extension to Non-Note Conflict-of-Interest Transactions:

While the majority opinion focused its explicit rationale for protecting third parties on the "circulating nature" of promissory notes, Justice Osumi's influential supplementary opinion argued forcefully that the principle of "relative invalidity" and the protection of good-faith third parties should logically extend to all direct conflict-of-interest transactions, not just those involving negotiable instruments. For example, if a company sold real estate to a director without board approval, and that director then sold it to a bona fide third party, that third party should also be protected. This broader interpretation has largely been embraced in subsequent case law and academic theory. Indeed, a 1968 Grand Bench decision had already applied a similar "relative invalidity" approach to indirect conflict-of-interest transactions (where a director has an interest in a deal between the company and another entity). - The Standard of "Bad Faith" for the Third Party:

The judgment places the burden on the company to prove that the third-party holder of the note was in "bad faith." This means the company must show that the third party knew it was a director-company transaction and knew that board approval was lacking. While the majority opinion did not explicitly state whether "gross negligence" on the part of the third party would suffice to be treated as bad faith, Justice Osumi's supplementary opinion suggested it should. This aligns with developments in other areas of Japanese commercial law (such as the doctrine of apparent representative director, as seen in a 1977 Supreme Court case), where gross negligence by a third party can vitiate their good faith claim. It is now generally understood that if a third party was grossly negligent in failing to recognize the conflict of interest and lack of approval, they might not receive protection. - Relationship with General Negotiable Instrument Law:

The Court's statement that Article 16, Paragraph 2 of the Bills of Exchange Act (protecting a holder in due course from personal defenses) does not apply might seem counterintuitive. However, the company's defense here is not a "personal defense" relating to the underlying transaction (which can be "cut off"). Instead, it's a defense asserting that the company's very act of drawing the note was fundamentally flawed due to a critical internal corporate governance failure (lack of board approval for a self-dealing transaction). The protection for the third party, therefore, arises not from the general rules of negotiable instruments cutting off defenses, but from the Supreme Court's specific interpretation of the Commercial Code's conflict-of-interest provisions and the balance struck to protect transaction safety. Alternative legal theories, such as the "creation theory" (sōzōsetsu) favored by some justices and the High Court, attempted to reconcile this more directly with negotiable instrument law by separating the formal act of creating a note obligation from its delivery in a conflict-of-interest context, but the Grand Bench majority opted for its "relative invalidity" framework rooted in the Commercial Code's director liability provisions.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court Grand Bench's decision of October 13, 1971, was a pivotal moment in Japanese corporate and commercial law. By decisively shifting from a doctrine of "absolute invalidity" to one of "relative invalidity" for promissory notes issued by a company to its director without required board approval, the Court significantly bolstered the safety and fluidity of transactions involving negotiable instruments. It established that while such unapproved transactions remain unenforceable by the director against the company, a good-faith third party who subsequently acquires the note is protected. The company cannot invoke its internal governance failure to defeat the claim of such a third party unless it can prove the third party's bad faith regarding the nature of the transaction and the lack of approval. This landmark ruling underscored the Supreme Court's commitment to balancing the internal governance requirements designed to protect corporate and shareholder interests with the broader societal need for certainty and security in commercial dealings.