Confidentiality in Court: Japan's Supreme Court on a Psychiatrist's Duty in Expert Evaluations

Decision Date: February 13, 2012, Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench (Heisei 22 (A) No. 126)

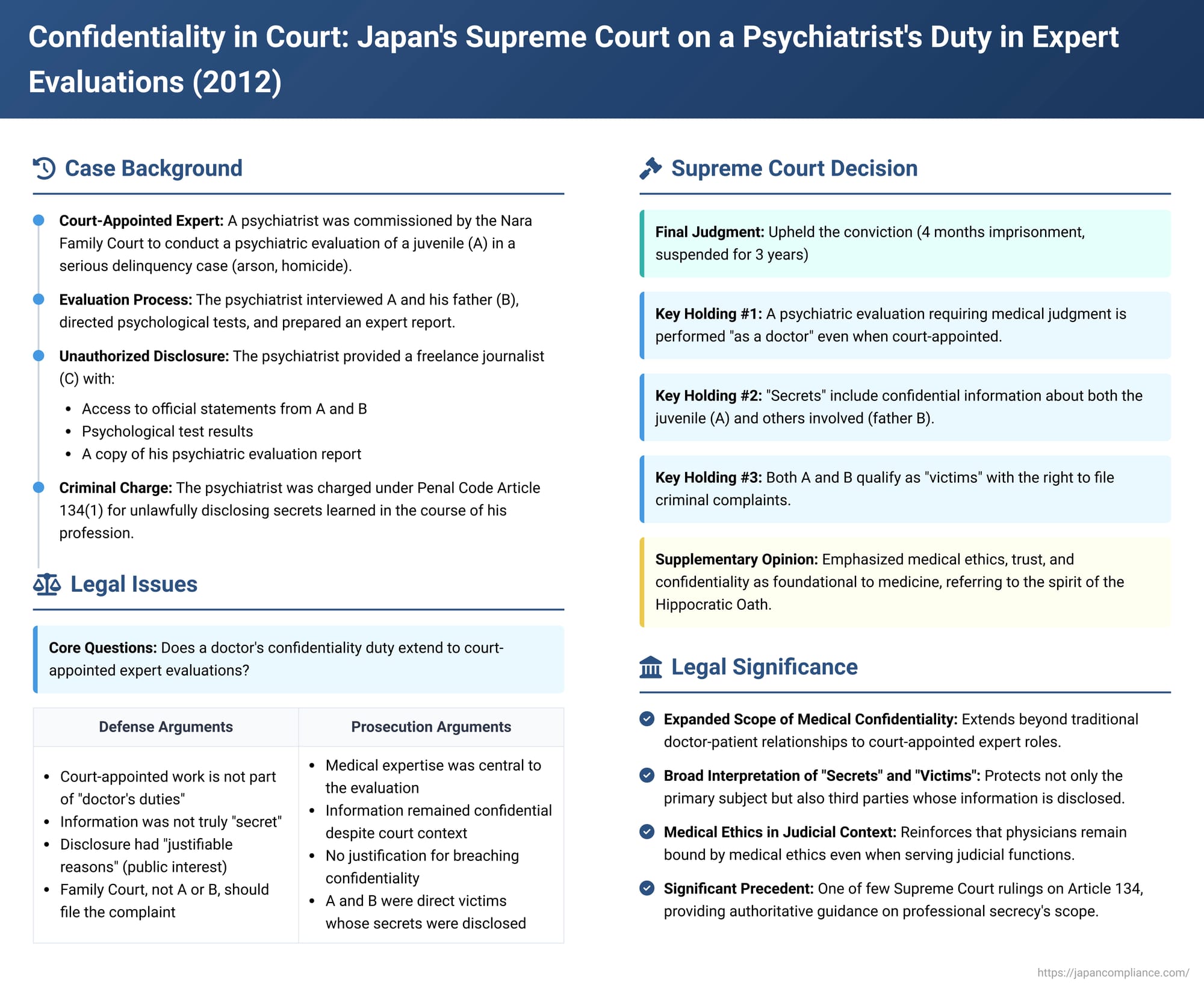

In a significant ruling dated February 13, 2012, the Supreme Court of Japan addressed the delicate intersection of medical ethics, professional secrecy, and court-appointed expert evaluations. The Court upheld the conviction of a psychiatrist for unlawfully disclosing confidential information obtained while conducting a psychiatric assessment of a juvenile for a Family Court. This decision clarifies the breadth of a doctor's duty of confidentiality under Japanese law, extending it robustly to contexts beyond traditional patient-doctor therapeutic relationships.

The Factual Background: A Psychiatrist, A Juvenile Case, and a Journalist

The defendant was a psychiatrist commissioned by the Nara Family Court to conduct an expert psychiatric evaluation. The subject of the evaluation was a juvenile, identified as A, who was involved in serious delinquency proceedings, including charges of arson of an inhabited structure and homicide.

The court's mandate for the psychiatrist was to report on:

- The psychiatric background of A's delinquent acts.

- A's mental state, both at the time of the offenses and at the time of the evaluation.

- Any other matters that would be参考に (sankou ni naru – serve as a reference) for determining A's appropriate disposition or treatment.

To fulfill this mandate, the defendant psychiatrist interviewed A and A's father, B. He also directed a clinical psychologist and laboratory technicians to conduct psychological tests and physical examinations on A.

The case arose when the psychiatrist, responding to a request from a freelance journalist, C, disclosed substantial amounts of information gathered during this evaluation. The disclosures included:

- Allowing C to view copies of official statements (供述調書 - kyojutsu chosho, 陳述調書 - chinjutsu chosho) made by A, B, and others, which had been provided to the psychiatrist by the Nara Family Court as鑑定資料 (kantei shiryo – evaluation materials).

- Permitting C to view and transcribe a document containing the results of A's psychological tests, which had been prepared by the clinical psychologist.

- Providing C with a copy of the psychiatric evaluation report on A that the defendant himself had authored.

The Legal Charge: Unlawful Disclosure of Secrets

The psychiatrist was charged under Article 134, Paragraph 1 of the Penal Code of Japan. This provision criminalizes the act of a "physician, pharmacist, pharmacist's assistant, midwife, attorney (including a foreign lawyer registered in Japan), notary, or a person formerly engaged in any of these professions" who, "without justifiable reason, discloses a secret which has come to his/her knowledge in the course of conducting his/her profession."

This offense is classified as a 親告罪 (shinkokuzai), meaning it is a crime prosecutable only upon a formal complaint (告訴 - kokuso) lodged by the victim or other specified individuals who have the right to complain.

Arguments Before the Courts

The defendant and his counsel admitted to the factual acts of disclosure but raised several defenses:

- Not within the Scope of "Doctor's Duties": They argued that the duties of a court-appointed expert witness are distinct from the professional duties of a physician. Therefore, the information disclosed was not obtained "in the course of conducting his/her profession" as a doctor.

- Information Not "Secret": It was contended that the information, particularly court documents, might eventually become public through trial proceedings, so A and B would have anticipated some level of disclosure, negating its confidential nature.

- Justifiable Reason: The defendant asserted that his actions were motivated by a desire to benefit A and to serve the public interest by cooperating with journalist C's investigative reporting. This, he argued, constituted a "justifiable reason" that should negate the illegality of the disclosure.

- Invalid Complaint: They claimed that the proper party to file a criminal complaint, if any, was the Nara Family Court, which had commissioned the evaluation, not A or B (the juvenile and his father). Since the Family Court had not filed a complaint, the prosecution was invalid.

- Abuse of Prosecutorial Discretion: It was alleged that the prosecution was politically motivated, aiming to curb reporting on juvenile crime, and thus represented a significant deviation from prosecutorial discretion, warranting dismissal.

The Nara District Court, and subsequently the Osaka High Court on appeal, rejected all these defense arguments. The psychiatrist was found guilty and sentenced to four months of imprisonment, suspended for three years. The defendant then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision

The Supreme Court dismissed the final appeal, affirming the lower courts' guilty verdicts. The Court's reasoning focused on several key interpretations of Article 134, Paragraph 1:

1. Is a Court-Appointed Psychiatric Evaluation part of a "Doctor's Duties"? Yes.

The Court held that when a physician is appointed to conduct an expert evaluation that necessitates medical judgment, including diagnosis, based on their specialized knowledge and experience as a physician, the performance of that evaluation is indeed an act carried out "as a doctor" within the meaning of the statute. The crucial factor is the nature of the work performed—leveraging medical expertise for assessment and judgment—rather than the identity of the entity requesting the service (e.g., a court versus a direct patient). The act of providing a psychiatric opinion based on such evaluation is intrinsically linked to the physician's professional capacity.

2. Whose "Secrets" are Protected? Those of the Evaluaee and Others Involved.

The term "a person's secret" (人の秘密 - hito no himitsu) under Article 134, when applied to a court-ordered medical evaluation, is not confined to the secrets of the primary subject of the evaluation (juvenile A). It also encompasses confidential information pertaining to other individuals (such as A's father, B) that the physician comes to know during the course of conducting the evaluation. This means that if a doctor, in the process of a court-appointed psychiatric assessment of a juvenile, learns private details about the juvenile's family members relevant to the assessment, those details also qualify as protected secrets if disclosed without justification.

3. Who is a "Victim" with the Right to Complain? The Individuals Whose Secrets Were Disclosed.

Given the above, the Supreme Court concluded that the individuals whose personal secrets were unlawfully disclosed—in this case, both the juvenile A and his father B—are "persons harmed by the crime" (犯罪により害を被った者 - hanzai ni yori gai wo koumutta mono) as stipulated in Article 230 of the Code of Criminal Procedure. Consequently, both A and B possessed the legal right to file a criminal complaint against the psychiatrist. This finding validated the procedural basis of the prosecution, countering the defense's argument that only the Family Court could complain.

Based on these interpretations, the Supreme Court found that the defendant's actions in disclosing the secrets of A and B constituted a violation of Article 134, Paragraph 1 of the Penal Code, and upheld the lower courts' judgments as legitimate.

The Supplementary Opinion: Ethical Foundations of Medical Secrecy

One of the justices of the Supreme Court provided a supplementary opinion to further elaborate on the underpinnings of the decision. This opinion offered deeper insights into the ethical dimensions of medical confidentiality:

- Trust as the Bedrock: The justice emphasized that the core of a physician's practice, particularly clinical activities like diagnosis and treatment, is fundamentally built upon a relationship of trust with the patient (or those acting for them). This trust encourages patients to voluntarily disclose highly personal and private information—their symptoms, medical history, and other sensitive details about their physical and mental condition—which is essential for effective medical care. Article 134, in relation to physicians, primarily aims to protect these patient secrets. Secondarily, or reflexively, it aims to protect the integrity of medical practice itself by ensuring that patients feel secure in revealing necessary information to their doctors.

- Nature of the Evaluation in This Case: While some forms of expert witness work performed by physicians might seem distant from direct clinical care (e.g., a purely document-based review), the specific tasks undertaken by the defendant in this case were deemed closely analogous to fundamental medical practice. These tasks included conducting personal interviews with the juvenile and his parents, performing psychological and physical examinations (albeit through instruction), diagnosing the juvenile's mental state, and offering opinions on measures for his rehabilitation. This comprehensive process was seen as very similar to the diagnostic and therapeutic work a doctor would undertake with a patient.

- The Doctor's Overarching Ethical Duty: The justice posited that Article 134 focuses on the physician as a professional who, by virtue of their role, is privy to sensitive personal information. Society places a high ethical expectation on physicians to be trustworthy guardians of such secrets. The provision penalizes the disclosure of protected secrets (which are not limited strictly to "patient" secrets in the narrowest sense) as an ethically reprehensible act.

- Echoes of the Hippocratic Oath: The supplementary opinion invoked the spirit of the Hippocratic Oath, particularly its injunction to maintain silence concerning things seen or heard in the course of medical practice (or even outside of it) that ought not to be spread abroad. This reference underscored the profound and longstanding ethical principle that physicians should scrupulously guard personal secrets, a principle the justice saw as foundational to Article 134.

Ultimately, the supplementary opinion concurred that the defendant's disclosure of secrets learned during his expert evaluation, an act belonging to his duties as a physician, was not only a breach of an expert witness's ethics but also fulfilled the constituent elements of the crime of unlawful disclosure of secrets under the Penal Code.

Analysis and Significance of the Decision

This Supreme Court ruling is a critical precedent in Japanese law concerning professional secrecy, particularly for medical practitioners serving in quasi-judicial roles.

- Clarification on "Doctor's Duties": The decision firmly establishes that a physician's responsibilities under Article 134 are not confined to traditional therapeutic settings. When a court commissions a physician for an expert evaluation that draws upon their core medical knowledge, diagnostic skills, and experience, the activities undertaken in that context are considered part of their professional duties "as a doctor". This counters arguments that such roles are purely those of an "expert witness" and somehow detached from the ethical and legal obligations attendant to the medical profession. The focus is on the substance of the task (application of medical expertise) rather than the formal label of the engagement.

- Broad Scope of "Secrets" and "Persons Harmed": The ruling significantly clarifies that the "secrets" protected are not just those of the direct subject of an evaluation. If, in the course of that evaluation, the physician learns confidential information about third parties (like family members), that information is also protected. Consequently, these third parties also gain the status of "victims" with the right to file a criminal complaint if their secrets are unlawfully disclosed. This interpretation is crucial for protecting the privacy of individuals who become involved in such evaluations indirectly. The PDF commentary supports this, arguing that the law aims to protect "secrets" broadly and ensure the smooth functioning of professions that handle such information, making it inappropriate to limit protection only to direct clients.

- The "Justifiable Reason" Defense: While the Supreme Court's main opinion did not extensively dissect the "justifiable reason" defense, its affirmation of the lower courts' verdicts implies agreement with their rejection of this claim. The lower courts likely performed a balancing act, weighing the defendant's stated motives (A's benefit, public interest through journalism) against several countervailing factors: the disclosure occurred while the juvenile's sensitive case was still pending in Family Court (which operates under principles of confidentiality to protect minors); the claimed public interest did not clearly outweigh the strong interest in maintaining the confidentiality of juvenile proceedings; and the method of disclosure (providing extensive, unfiltered access to sensitive documents to a journalist) was arguably disproportionate and highly detrimental to the privacy of A and B. The commentary emphasizes that while cooperation with the press is important, it must be carefully weighed against the potential harm caused by leaking confidential information, especially in sensitive medical and juvenile justice contexts.

- Defining "Secret": The defense had argued that some of the disclosed information (e.g., court statements) might not qualify as "secret" because A and B might have anticipated their use in court. However, as legal commentary associated with the case points out, a "secret" under Japanese law generally refers to a non-public fact that either has an objective interest in being kept confidential or which the subject has explicitly indicated a desire to keep confidential. The information disclosed here included highly personal details about A's upbringing, academic performance, B's approach to parenting A, and the raw results of psychological and psychiatric evaluations—all of which possess a strong element of privacy. The mere possibility of limited, controlled disclosure within court proceedings does not equate to consent for unrestricted dissemination to the media, especially concerning a minor involved in delinquency proceedings.

- Disparity with Non-Medical Experts: An interesting legal point, highlighted in commentary, is the potential disparity in treatment between physicians acting as expert witnesses and other professionals (e.g., a psychologist who is not also a medical doctor) performing similar evaluative roles. If a non-physician psychologist had disclosed the same information, they might not have been liable under Article 134, as there is no general penal statute criminalizing the disclosure of secrets by all types of court-appointed experts. This difference is seen not as a violation of the principle of legality (nullum crimen sine lege) but as a reflection of the historically fragmented nature of Japanese criminal legislation concerning professional secrecy. The current ruling applies specifically to physicians due to their explicit inclusion in Article 134.

- Importance as Precedent: Given the scarcity of Supreme Court rulings on Article 134 of the Penal Code, this decision carries substantial weight. It provides authoritative guidance on several contested aspects of the law, particularly its application to physicians engaged in forensic or evaluative work for the courts.

In conclusion, the Supreme Court's 2012 decision sends a clear message: physicians, even when acting outside the traditional confines of a patient-initiated therapeutic relationship, remain bound by a stringent duty of confidentiality. When their medical expertise is enlisted by the courts, the information they handle—pertaining to the subject of evaluation and relevant third parties—is protected under criminal law, and breaches can lead to significant legal consequences. This underscores the high ethical and legal standards expected of medical professionals in all facets of their work.