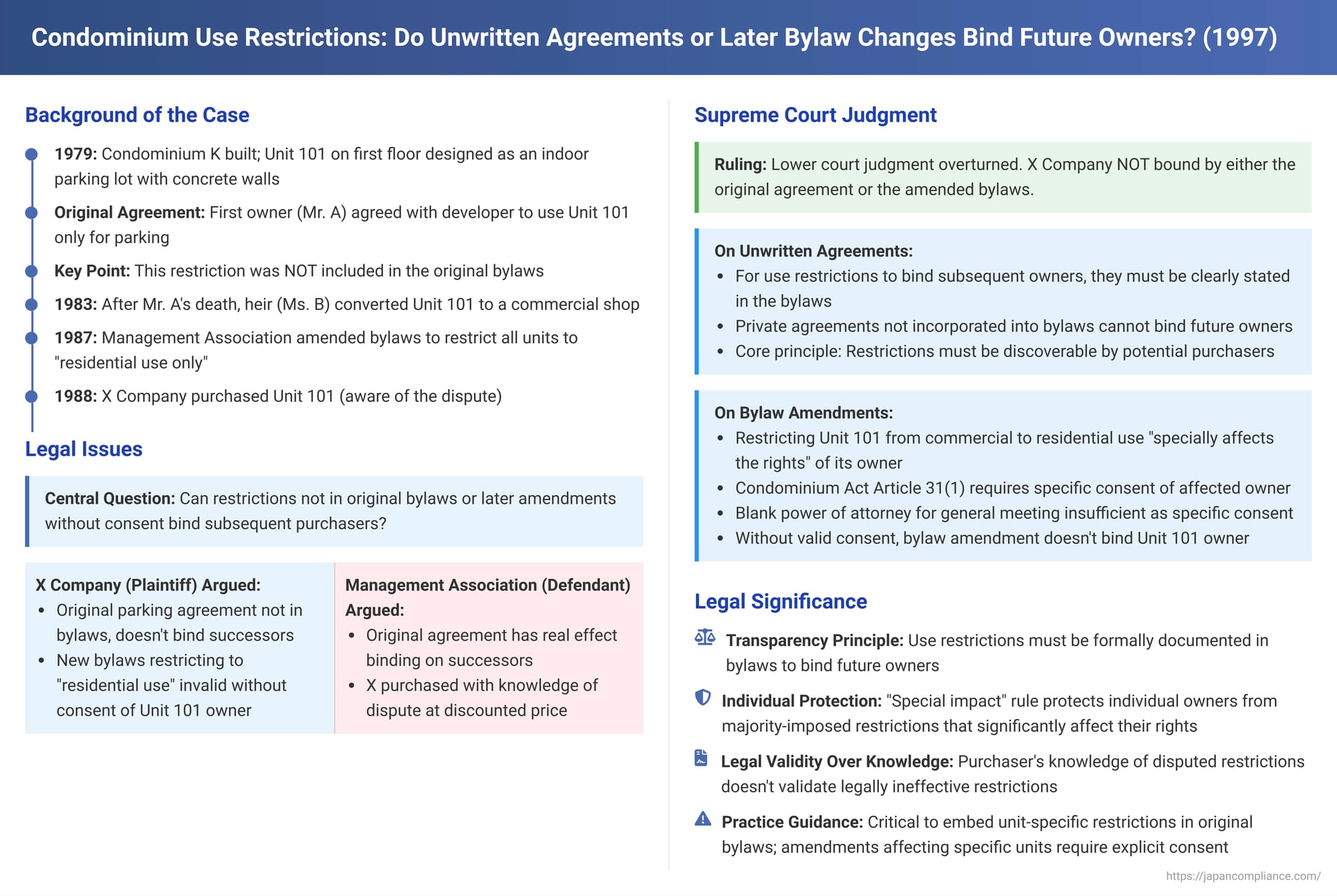

Condominium Use Restrictions: Do Unwritten Agreements or Later Bylaw Changes Bind Future Owners? A 1997 Japanese Supreme Court Ruling

Date of Judgment: March 27, 1997

Case Number: 1992 (O) No. 279 (Supreme Court, First Petty Bench)

Introduction

Condominiums often come with specific rules about how individual units can be used, aiming to maintain a certain living environment or character for the community. These use restrictions can be crucial for residents' expectations and property values. However, questions frequently arise about how such restrictions are legally established and, more importantly, whether they remain binding on those who later purchase units, especially if the restrictions are not explicitly clear in the governing documents from the outset or if bylaws are subsequently changed.

A key Japanese Supreme Court decision on March 27, 1997, delved into these issues, examining whether a contractual use restriction agreed upon by an original unit owner but not formalized in the initial bylaws could bind subsequent owners. The Court also considered the validity of a later bylaw amendment that imposed a new, more stringent use restriction on a unit with a unique history, particularly focusing on the requirement for the affected owner's consent.

Facts of the Case

The dispute centered around Unit 101 in "Condominium K," a building constructed in 1979 primarily as a residential condominium.

Original Design and Use of Unit 101:

- Condominium K's upper floors (second floor and above, with the main entrance on the second floor) were sold as residential units.

- Unit 101, located on the first floor, was uniquely designed as an indoor parking lot, consisting of concrete walls and pillars, with direct access to the north-side road. Its appraised value was presumably lower than the residential units.

- The original owner of the land on which Condominium K was built, Mr. A, acquired ownership of Unit 101 through an "equivalent exchange" (等価交換 - tōka kōkan) with the condominium developer.

- Mr. A entered into a contractual agreement with the developer stipulating that Unit 101 would be used as an indoor parking lot and that its use would not be changed to anything other than parking without the consent of the other unit owners. This agreement was not incorporated into Condominium K's original bylaws ("Old Bylaws").

- Initial sales advertisements for Condominium K had presented Unit 101 as parking available for unit owners, and Mr. A did, in fact, lease Unit 101 to other unit owners for parking purposes.

Original Bylaws and Building Code Restrictions:

- The Old Bylaws (原始規約 - genshi kiyaku) of Condominium K (Articles 15 and 16) contained a general restriction prohibiting unit owners from using their private units for non-residential purposes such as "restaurants, snack bars, coffee shops, bars, clubs, hotels, and other similar late-night businesses." However, there were no provisions in the Old Bylaws or associated use regulations that specifically restricted Unit 101's use exclusively to parking.

- At the time Condominium K was built, local building code regulations concerning floor area ratios effectively meant that Unit 101 could not legally be used for any purpose other than parking. The total floor area of the building would have exceeded permissible limits if Unit 101 were used for other purposes.

- The owners of the residential units in Condominium K purchased their units with the expectation that the building would maintain its residential character and did not anticipate Unit 101 being converted into a commercial shop.

Succession of Ownership and Change in Use of Unit 101:

- Mr. A passed away in March 1980. Ms. B inherited ownership of Unit 101 by bequest.

- In 1983, Ms. B converted Unit 101 into a commercial shop space. She had the official property registration changed from "parking lot" to "shop" and leased it to C Company.

- Unit 101 was later sold by Ms. B to a third party. Subsequently, D Company, which had taken over the lease from C Company and was operating a boutique in Unit 101, acquired full ownership of the unit in June 1986.

Establishment of the Management Association and Adoption of New Bylaws:

- In October 1986, Y, the Management Association for Condominium K (the defendant/appellee in the Supreme Court case), was formally established.

- On February 13, 1987, an extraordinary general meeting of the Management Association Y approved a revision of the Condominium K's bylaws. Article 12 of these "New Bylaws" (新規約 - shin kiyaku) stipulated that private units "shall be used exclusively as residences" and were not to be used for non-residential purposes such as shops, offices, or warehouses.

- It was alleged that D Company (the owner of Unit 101 at the time) had submitted a blank power of attorney for this general meeting.

Further Sale of Unit 101 and Emergence of the Dispute:

- On March 19, 1987, D Company sold Unit 101 to E Company.

- Upon being notified of this sale, Management Association Y informed E Company that using Unit 101 for non-residential purposes was not permissible.

- Faced with this opposition, E Company approached X Company (the plaintiff/appellant), an acquaintance in the real estate business, explained the situation, and asked X Company to purchase Unit 101.

- X Company, fully aware of the ongoing dispute with Management Association Y and prepared for potential litigation if an agreement could not be reached, purchased Unit 101 from E Company on March 30, 1988. The purchase price paid by X Company was noted to be considerably lower than the prevailing market value for similar properties.

Change in Building Code Regulations:

In October 1989, the floor area ratio regulations applicable to the Condominium K site were amended. This change made it legally permissible under the building codes for Unit 101 to be used for purposes other than parking.

The Lawsuit:

X Company initiated a lawsuit against Management Association Y and other unit owners. X Company sought:

- A judicial confirmation that, apart from the Old Bylaws' prohibition against use as a "restaurant, etc.," there were no other use restrictions on Unit 101.

- A confirmation that Unit 101's ownership rights per unit area were identical in terms of rights and obligations to other private units in Condominium K.

- Damages for alleged tortious acts by Y in preventing X Company from using Unit 101 as a shop.

Management Association Y filed a counterclaim, primarily seeking an injunction to prohibit X Company from using Unit 101 for any purpose other than parking. Alternatively, Y sought to prohibit its use for any purpose other than as a residence.

Lower Court Rulings:

- First Instance Court (Tokyo District Court): Dismissed X Company's main claims. It granted Management Association Y's alternative counterclaim, effectively prohibiting X Company from using Unit 101 for non-residential purposes.

- High Court (Tokyo High Court): Dismissed X Company's appeal. The High Court found that the original contractual restriction (to use Unit 101 only as parking) agreed to by Mr. A, although a private agreement, had acquired a "real effect" (対物的効力 - taibutsu-teki kōryoku) that was binding on subsequent purchasers of Unit 101. It reached this conclusion by analogy to Article 46, Paragraph 1 of the Condominium Ownership Act (COA) (which states that bylaws bind specific successors) and considering COA Article 31, Paragraph 1 (which requires an affected owner's consent for bylaw changes that specially impact their rights). The High Court also held that Article 12 of the New Bylaws (restricting use to residential only) applied to Unit 101.

X Company appealed the High Court's decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Judgment

The Supreme Court, in its decision of March 27, 1997, overturned the High Court's judgment and remanded the case for further proceedings. The Supreme Court's reasoning focused on the legal requirements for use restrictions to bind subsequent purchasers and the conditions for validly amending bylaws when such amendments "specially affect" an owner's rights.

1. Effectiveness of Bylaws Against Subsequent Purchasers:

The Supreme Court referenced the (now former) Condominium Ownership Act provisions (Article 23, allowing bylaws to regulate matters concerning the use of the building among unit owners, and Article 25, stating that bylaws are effective against specific successors of unit owners – principles carried over into current COA Articles 30 and 46).

- It highlighted the underlying rationale: condominium ownership has special characteristics. A prospective purchaser of a condominium unit can, and is expected to, examine the bylaws. This inspection allows them to become aware of any existing restrictions or special conditions that apply to the property they intend to acquire.

2. The Imperative for Explicit Bylaw Provisions to Bind Successors:

Based on this rationale, the Supreme Court laid down a clear principle:

- For a use restriction on a private unit to be binding on subsequent purchasers (specific successors), it must be uniformly and clearly stated in the condominium's bylaws. (Under current law, this would extend to resolutions of a general meeting as well).

- A mere contractual agreement on use restriction made by a former owner (such as the agreement between Mr. A and the developer regarding Unit 101 being used only for parking) cannot be readily equated with a restriction formally established and documented in the bylaws. Such private agreements, not being part of the publicly accessible bylaws, do not meet the requirement of discoverability by potential purchasers.

Application to the Original "Parking Only" Agreement:

Since the agreement by Mr. A to use Unit 101 exclusively as a parking lot was not stipulated in the Old Bylaws, the Supreme Court found that this contractual restriction did not bind subsequent purchasers of Unit 101, including X Company.

3. Validity of the New Bylaw's Article 12 (Residential Use Only) as Applied to Unit 101:

The Supreme Court then addressed the High Court's finding that Article 12 of the New Bylaws (restricting all units to "exclusively residential use") applied to Unit 101.

- The Court first questioned whether the wording of Article 12, which appeared to refer to "unit owners who acquired residential units," was even clearly applicable to Unit 101, given its distinct original design and purpose as a parking lot.

- Assuming, for the sake of argument, that Article 12 did apply to Unit 101, the Supreme Court found a more fundamental issue. Restricting Unit 101 – which was originally designed as non-residential (parking) and had subsequently been used for commercial purposes (a boutique) – to "exclusively residential use" would constitute a measure that "specially affects the rights" (特別の影響を及ぼすべきとき - tokubetsu no eikyō o oyobosu beki toki) of the owner of Unit 101. This triggers a specific protective provision in the Condominium Ownership Act (Article 31, Paragraph 1, latter part).

- This COA provision requires that if a bylaw amendment "specially affects the rights of some unit owners," the specific consent of those affected unit owners must be obtained for the amendment to be valid with respect to them.

- At the time the New Bylaws were adopted, D Company was the owner of Unit 101. While D Company had allegedly submitted a blank power of attorney for the general meeting, the Supreme Court held that this was not sufficient to be recognized as D Company's specific, individual consent to such a significant and impactful restriction on the use of Unit 101.

4. X Company Not Bound by the Imposed Restrictions:

Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded:

- X Company, as a subsequent purchaser of Unit 101, was not bound by the original contractual agreement between Mr. A and the developer because it was not in the Old Bylaws.

- X Company was also not bound by Article 12 of the New Bylaws because the requisite specific consent from the then-owner (D Company) for this "specially impactful" restriction had not been validly obtained.

- This conclusion held true even when considering the various circumstances emphasized by the High Court, such as Unit 101's original design as parking, the expectations of other residential unit owners, X Company's knowledge of the dispute, and the reduced price at which X Company purchased the unit.

The Supreme Court found that the High Court had erred in its interpretation and application of the law. The case was remanded for further proceedings consistent with the Supreme Court's opinion. (The Supreme Court also noted that X Company's claim for confirmation of "identical rights and obligations per unit area" with other units was vaguely formulated and advised the High Court on remand to seek clarification from X Company on this point).

Analysis and Broader Implications

This 1997 Supreme Court decision carries significant weight in defining how use restrictions on condominium units are created and enforced, particularly against those who subsequently purchase the units.

1. The Primacy of Written, Discoverable Bylaws:

The judgment strongly reinforces the principle that for use restrictions to effectively bind all subsequent owners, they must be clearly, formally, and unambiguously documented within the condominium's bylaws. This emphasis on explicit bylaw provisions ensures transparency and predictability in condominium transactions. Potential buyers are expected to review the bylaws to understand the "rules of the road" for the property they are considering. "Side agreements," historical understandings, or even original design intentions, if not properly translated into formal bylaw restrictions, generally lack the power to bind future owners who were not party to those initial arrangements.

2. The "Special Impact" Rule as a Safeguard for Individual Owners (COA Article 31, Paragraph 1):

This rule is a cornerstone of protection for individual unit owners against the power of the majority in a condominium association. The Supreme Court's application in this case is illustrative:

- A bylaw amendment that drastically alters the permitted use of a specific unit (especially from a non-residential or particular specialized use to a much more restrictive one like "exclusively residential") is highly likely to be deemed as having a "special impact" on the rights of that unit's owner.

- When such a "special impact" occurs, the mere passage of the bylaw amendment by the standard general meeting majority is insufficient. The specific consent of the individually affected unit owner is required.

- The Court's finding that a blank power of attorney for a general meeting does not automatically constitute this specific consent for a deeply impactful restriction is noteworthy. It suggests that a more explicit and informed agreement from the affected owner is necessary.

3. Purchaser's Knowledge vs. Legal Validity of Restrictions:

The High Court had given considerable weight to the fact that X Company purchased Unit 101 with full knowledge of the ongoing dispute and at a significantly reduced price. However, the Supreme Court's decision indicates that such knowledge does not, in itself, validate an otherwise legally ineffective restriction. If a use restriction is not properly established in the bylaws, or if a bylaw amendment imposing it is invalid due to lack of required consent for a "special impact," a subsequent purchaser's awareness of attempts to enforce such a restriction does not retroactively make it binding upon them. The core issue remains the legal validity of the restriction itself.

4. Discouraging Reliance on Informal or Unwritten Restrictions:

The ruling serves as a caution against relying on informal understandings, past contractual agreements not reflected in bylaws, or the "original intent" behind a development to restrict the use of condominium units against future owners. While original expectations and the initial nature of a building are relevant background, they cannot substitute for formally adopted and legally sound bylaw provisions when it comes to imposing restrictions that run with the land and bind all successors in title.

5. Practical Guidance for Condominium Governance:

- For Developers and Initial Set-Up: If a developer or the initial body of unit owners intends for specific use restrictions to apply to particular units (especially if these uses differ from the general pattern of the condominium, like a designated commercial space in a residential building or a parking-only unit), it is absolutely crucial to embed these restrictions clearly and unambiguously in the original, registered bylaws of the condominium.

- For Subsequent Bylaw Amendments: When a management association considers amending its bylaws in a way that could alter or restrict the use of certain units, it must meticulously assess whether such amendments could have a "special impact" on the rights of any specific unit owner(s). If so, obtaining the explicit, individual consent of those affected owners is a legal prerequisite for the validity of that amendment as applied to them.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1997 judgment in this case champions the principles of legal certainty and transparency in condominium governance. It underscores that for use restrictions on private units to be binding on all subsequent purchasers, they must be clearly articulated within the condominium's formal bylaws. Furthermore, the Court robustly applied the "special impact" provision of the Condominium Ownership Act, ensuring that significant changes to a unit owner's rights through bylaw amendments require their specific and informed consent. This decision serves as a critical guide for condominium developers, management associations, and unit owners, highlighting the importance of formal documentation and due process in establishing and modifying the rules that govern life in a shared community.