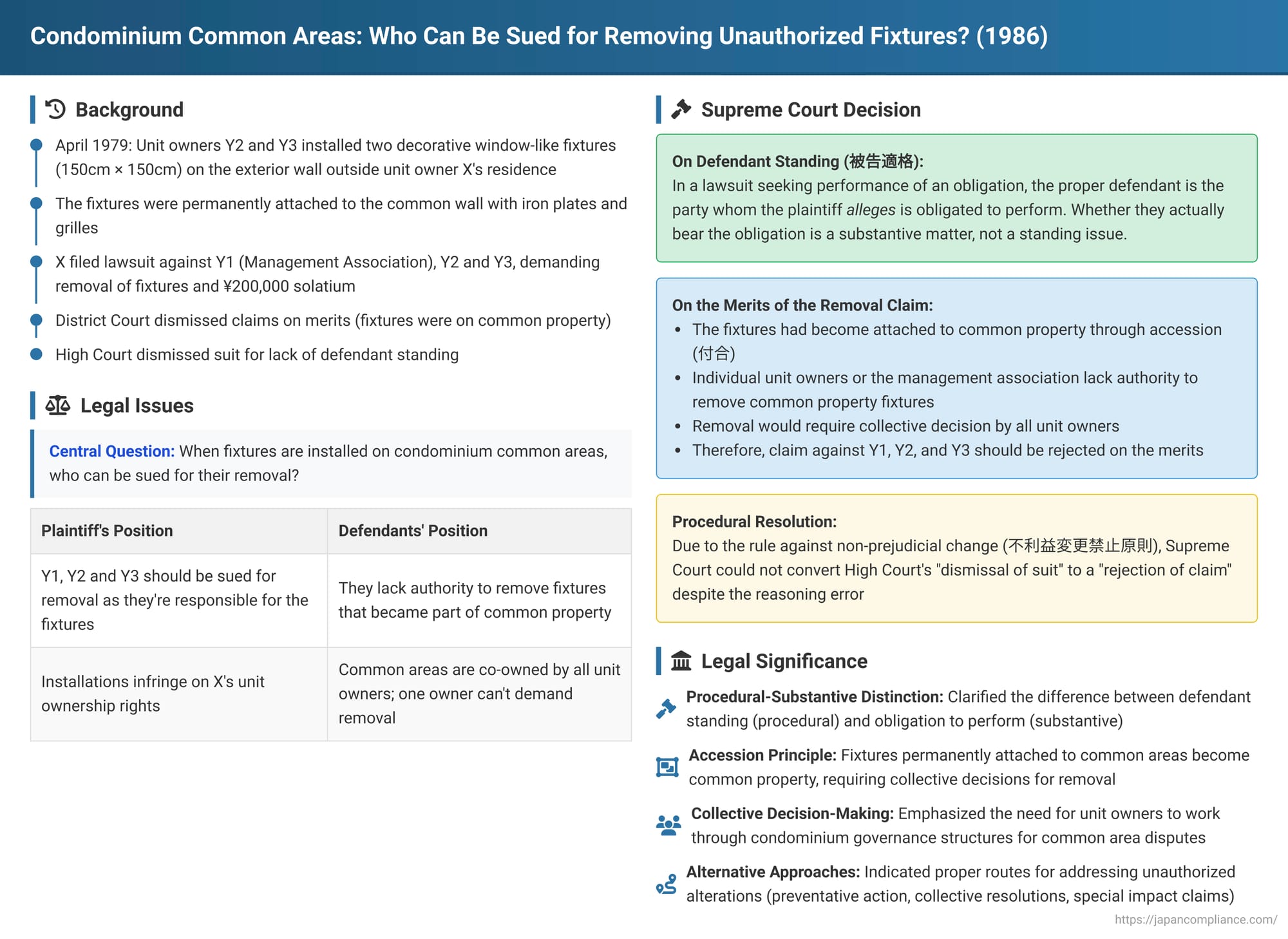

Condominium Common Areas: Who Can Be Sued for Removing Unauthorized Fixtures? A 1986 Japanese Supreme Court Decision

Date of Judgment: July 10, 1986

Case Number: 1983 (O) No. 582 (Supreme Court, First Petty Bench)

Introduction

Living in a condominium involves navigating the complexities of shared ownership and collective management of common areas. Disputes often arise when alterations or fixtures are made to these common areas, especially if one unit owner perceives them as an infringement on their rights or an unauthorized modification. A critical question in such scenarios is: if a unit owner wishes to have an offending fixture removed, who is the legally appropriate party to sue?

A Japanese Supreme Court judgment delivered on July 10, 1986, addressed this intricate issue, particularly focusing on the procedural concept of "defendant standing" (被告適格 - hikoku tekikaku) in relation to substantive claims concerning condominium common property. This case highlights the distinction between alleging an obligation and proving it, and the collective nature of decisions regarding common area alterations.

Facts of the Case

The dispute involved X, a unit owner on the second floor of a condominium ("the Building"), Y1, the Building's Management Association, and Y2 and Y3, two other unit owners who had been responsible for carrying out renovation work on the Building.

Installation of the Disputed Fixtures:

Around April 1979, Y2 and Y3, acting without the consent of X, installed two decorative, window-like fixtures, each approximately 150cm in height and width. These fixtures were permanently affixed with iron plates and grilles to the western exterior wall surface located outside what X asserted was X's private unit.

X's Claims:

X filed a lawsuit against Y1 (the Management Association), Y2, and Y3. X demanded:

- The removal of the two fixtures, alleging that their installation infringed upon X's unit ownership rights.

- Payment of ¥200,000 as solatium (慰謝料 - isharyō, compensation for emotional distress).

Lower Court Rulings:

- First Instance (Tokyo District Court, April 28, 1981):

The District Court acknowledged the defendant standing of Y1, Y2, and Y3. However, it dismissed all of X's claims on their merits. The court found that the western exterior wall in question was part of the Building's common areas, not X's private property. Therefore, the installation of the fixtures did not constitute work done on X's private unit. Furthermore, the court found no evidence that the fixtures obstructed light or ventilation to X's unit or otherwise infringed upon X's ownership rights. - High Court (Tokyo High Court, February 28, 1983):

The High Court took a significantly different approach regarding the removal claim.

It began by stating a general principle: a lawsuit seeking the removal of a specific object based on real rights (such as ownership) must be directed against a party who possesses the authority to dispose of that object.

The High Court found that the fixtures had become permanently attached to the common exterior wall and, through the legal principle of accession (付合 - fugō, pursuant to Article 242 of the Civil Code), had become integral parts of the common property. As such, the fixtures were now co-owned by all unit owners of the Building.Based on this, the High Court reasoned:Consequently, the High Court concluded that Y1, Y2, and Y3 all lacked the necessary authority to dispose of (and therefore remove) the fixtures. On this basis, it ruled that they lacked defendant standing for the removal claim. The High Court therefore overturned the first instance court's decision (which had dismissed the removal claim on the merits) and instead dismissed X's suit for removal as being improperly brought against parties without standing.- Y1 (the Management Association): Its authority, as defined by its bylaws, was limited to "conducting necessary operations and consultations regarding the management and use of the... common areas" and "maintenance and management of common areas." The removal of the fixtures, which had become part of the common property, would constitute an act of alteration or disposition, exceeding mere maintenance or management. The Condominium Ownership Act (Article 18 of the pre-1983 version, equivalent to the later Article 26) also did not grant such authority to the management association acting alone.

- Y2 and Y3: As individual unit owners, they had no independent authority to dispose of or alter common property, which is co-owned by all unit owners (a principle generally reflected in Article 251 of the Civil Code concerning co-owned property).

X appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Judgment

The Supreme Court delivered its judgment on July 10, 1986, addressing both the procedural issue of defendant standing and the substantive claim for removal.

1. On Defendant Standing (被告適格 - hikoku tekikaku):

The Supreme Court first addressed the High Court's dismissal of the suit for lack of defendant standing.

- It held that in a lawsuit seeking performance of an obligation (a "claim for performance" or 給付の訴え - kyūfu no uttae), such as the removal of an object, the proper defendant is the party whom the plaintiff alleges is obligated to render that performance.

- Whether the defendant actually bears such an obligation is a matter to be determined by examining the merits of the claim, not a preliminary question of whether the defendant has standing to be sued.

- Therefore, X's lawsuit, which alleged that Y1, Y2, and Y3 were obligated to remove the fixtures, was procedurally proper in terms of defendant standing. The High Court's decision to dismiss the suit on this basis was illegal.

2. On the Merits of the Removal Claim:

Despite finding the High Court's dismissal of the suit for lack of standing to be erroneous, the Supreme Court did not remand the case.

- It noted that the High Court, in the course of its (flawed) reasoning on standing, had already conducted a full examination of the substantive issue: whether Y1, Y2, and Y3 possessed the authority (and thus the obligation) to remove the fixtures. The parties had presented their arguments and evidence on this point.

- The Supreme Court concurred with the factual findings (which originated in the first instance court and were effectively upheld by the High Court regarding the nature of the wall and the fixtures) that:

- The external wall to which the fixtures were attached was indeed a common area of the Building.

- The fixtures had acceded to this common wall, thereby becoming part of the common property, co-owned by all unit owners.

- Given these facts, the Supreme Court concluded that Y1 (the Management Association, under its then-existing bylaws), Y2, and Y3 (as individual unit owners) did not, individually or collectively as the named defendants, possess the legal authority or obligation to remove the fixtures. Removal of an object that has become part of the common property generally requires a collective decision by all unit owners or an action taken pursuant to the specific provisions of the Condominium Ownership Act (e.g., a resolution for alteration of common areas).

- Thus, X's substantive claim for removal against these particular defendants was without merit and should ordinarily be rejected (請求棄却 - seikyū kikyaku).

3. Application of the Rule Against Non-Prejudicial Change (不利益変更禁止原則 - furieki henkō kinshi gensoku):

This rule became crucial to the final disposition of the appeal.

- The High Court had dismissed X's suit (訴え却下 - uttae kyakka).

- The Supreme Court found that the correct judgment on the merits should have been a rejection of the claim (請求棄却 - seikyū kikyaku).

- A "rejection of the claim" is a judgment on the substance of the dispute and creates res judicata, preventing the plaintiff from re-litigating the same claim against the same defendants. A "dismissal of the suit" for procedural reasons (like lack of standing, though incorrectly applied here) might, in some circumstances, allow the plaintiff to correct the procedural defect and sue again. Therefore, a "rejection of the claim" is generally considered a less favorable outcome for a plaintiff than a "dismissal of the suit."

- X was the appellant before the Supreme Court. The rule against non-prejudicial change (as it existed in the Code of Civil Procedure at the time: Articles 396 and 385, predecessors to current Articles 313 and 304) prevents an appellate court from rendering a judgment that is more disadvantageous to the appellant than the judgment being appealed, unless the appellee has also appealed or cross-appealed.

- Since changing the High Court's "dismissal of suit" to a "rejection of claim" would have been more prejudicial to X, the Supreme Court could not make this change.

- Therefore, while the High Court's reasoning for dismissing the suit (lack of defendant standing) was flawed, its ultimate outcome regarding the removal claim (the dismissal of X's case for removal) was maintained by the Supreme Court, which dismissed X's appeal on this point. The High Court's error in legal reasoning did not, in the end, affect the final outcome for X in the Supreme Court with respect to the removal claim.

4. Solatium Claim:

The appeal concerning the claim for ¥200,000 in solatium was dismissed because X failed to provide any specific reasons for appealing that part of the High Court's judgment.

Analysis and Broader Implications

This 1986 Supreme Court decision, while somewhat complex due to its procedural aspects, offers valuable insights into litigating claims related to condominium common areas.

1. Defendant Standing vs. Merits of the Claim:

The judgment clearly reaffirms a fundamental principle of civil procedure: in lawsuits demanding a certain action or performance, defendant standing is generally established if the plaintiff alleges that the named defendant is the party obligated to perform. The question of whether the defendant actually bears that obligation is a substantive issue to be decided on the merits of the case, typically leading to a rejection of the claim if the obligation is not proven, rather than a dismissal of the suit itself. The Supreme Court corrected the High Court's conflation of these two distinct concepts.

2. The "Exceptional Dismissal Theory" Context:

Academic discourse in Japan includes an "exceptional dismissal theory" (例外的却下説 - reigaiteki kyakka setsu), which suggests that in some performance claims, if it is patently obvious from the face of the pleadings that the defendant could not possibly be the responsible party, the court might exceptionally dismiss the suit for lack of defendant standing to avoid futile proceedings. However, the Supreme Court in this case adhered to the more standard view. Moreover, determining who has authority over condominium common property and fixtures attached thereto is rarely a simple matter discernible at a mere glance; it requires a substantive examination of facts, bylaws, and relevant statutes, as was done here.

3. Critiques of the High Court's Rationale on Standing:

The High Court's specific justification for denying defendant standing – that a judgment for removal against someone without disposal power would be ineffective if a true owner with disposal rights later objected (e.g., via a third-party objection suit against execution) – has been criticized by commentators. The enforceability of a judgment and the rights of third parties are generally considered distinct from the initial question of whether the plaintiff has sued the party alleged to be responsible. If the defendant is found not to be responsible on the merits, the claim is rejected, and no unenforceable order is issued against them.

4. The Crucial Role of Accession (付合 - fugō):

The determination that the decorative fixtures had acceded to the common exterior wall, thereby becoming part of the common property, was pivotal to the substantive outcome. Once an item accedes to common property, it becomes co-owned by all unit owners. Its disposition, alteration, or removal ceases to be a matter for the original installer (like Y2 and Y3) or even the management association acting under general maintenance powers (like Y1, whose authority was found to be limited by its bylaws to maintenance and not alteration). Such actions typically require a collective decision of all unit owners, often through formal resolutions as prescribed by the Condominium Ownership Act (e.g., a resolution for "changes" to common areas, which might require a special majority).

5. Alternative Approaches for the Aggrieved Unit Owner (X):

Given the legal framework, how could a unit owner like X have potentially addressed the unauthorized fixtures more effectively?

- Preventative Action: If X had become aware of the installation plans beforehand or while they were in progress, X might have sought an injunction to prevent the installation if it could be shown to be an unauthorized alteration of common property or an infringement on X's rights.

- Collective Action through the Management Association: Once the fixtures were installed and deemed part of the common property, the primary route for seeking their removal would be through the condominium's collective governance mechanisms. X could have:

- Proposed a resolution at a general meeting of unit owners to have the fixtures removed by the management association (or by contractors engaged by it).

- If such a resolution were passed, and the management association or responsible parties failed to act, X (or other unit owners) could then potentially sue to enforce the collective decision.

- Claiming "Special Impact": If X could demonstrate that the fixtures had a "special impact" on the use of X's private unit (e.g., significant loss of light, view, or ventilation – though the first instance court found no such impact in this case), X might have argued under the Condominium Ownership Act that such an alteration to common areas required X's specific consent, and lacking such consent, the alteration was improper.

6. Practical Realities of Modifying Common Property:

The case underscores the practical difficulties an individual unit owner may face in unilaterally compelling the removal of items that have become integrated into condominium common property, even if the initial installation was disputed. The legal framework strongly favors collective decision-making for any actions that amount to an alteration or disposition of common elements. This is intended to protect the shared interests of all co-owners and ensure that changes are made according to agreed-upon procedures and with proper authority.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1986 judgment in this case serves as an important reminder of the distinction between procedural defendant standing and the substantive merits of a claim in Japanese civil litigation, particularly for lawsuits demanding performance. While a plaintiff can generally sue the party they allege to be responsible, the claim will only succeed if that responsibility is proven.

More substantively, the decision illustrates how the principles of property law, such as accession, interact with the specific legal regime governing condominiums. Alterations or fixtures that become part of common property fall under the collective management of all unit owners. Their removal is not typically within the unilateral power of the original installers, individual unit owners, or even a management association acting under general maintenance mandates, but rather requires a decision made in accordance with the Condominium Ownership Act and the condominium's bylaws. This case reinforces the need for unit owners to utilize the collective governance structures of their condominium association to address disputes concerning common areas.