Condominium Bulk Electricity Contracts vs. Individual Choice: A 2019 Japanese Supreme Court Ruling

Date of Judgment: March 5, 2019

Case Number: 2018 (Ju) No. 234 (Supreme Court, Third Petty Bench)

Introduction

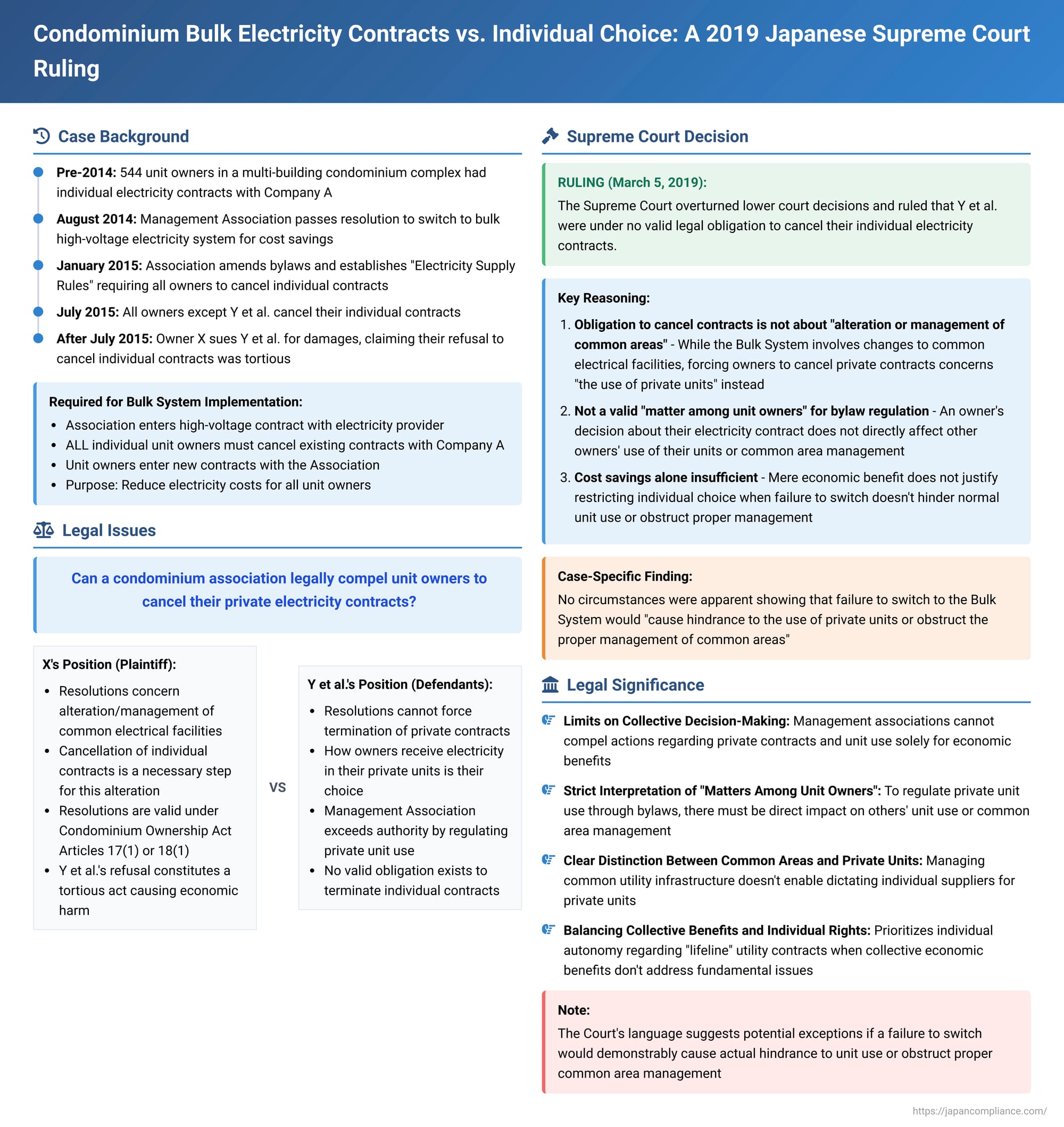

Condominium management associations in Japan frequently explore ways to reduce common expenses and individual living costs for their unit owners. One such strategy involves switching from individual electricity supply contracts for each unit to a bulk purchasing system, where the association contracts for high-voltage electricity at a potentially lower rate and then distributes it to residents. While economically attractive, this often requires unanimous participation, including the cancellation of existing individual contracts by all unit owners. This raises a significant legal question: Can a management association, through its resolutions or bylaws, legally compel all unit owners to terminate their private electricity contracts to facilitate such a switch?

A Supreme Court decision on March 5, 2019, provided critical insight into the limits of a management association's power to impose such obligations on its members, balancing collective benefits against individual contractual freedom and rights concerning the use of private property.

Facts of the Case

The dispute involved X and Y et al., all of whom were unit owners in "the Condominium," a large multi-building complex (団地 - danchi) consisting of five buildings and a total of 544 units.

Existing Electricity Supply Arrangement:

Unit owners and occupants of units within the Condominium (collectively, "Unit Owners, etc.") each had individual electricity supply contracts ("Individual Contracts") with Company A, a regional electricity provider. Electricity was delivered to their private units (専有部分 - sen'yū bubun) through the Condominium's common electrical facilities (団地共用部分 - danchi kyōyō bubun).

The Proposed Switch to a Bulk System:

In August 2014, a regular general meeting of the Condominium's incorporated management association ("the Association") passed a resolution to change to a bulk high-voltage electricity supply system ("the Bulk System"). The plan was for the Association to enter into a single high-voltage electricity supply contract with an electricity provider. Subsequently, Unit Owners, etc., would then enter into new contracts with the Association to receive electricity for their private units. The primary objective of this change was to reduce the electricity charges for each unit owner.

A critical prerequisite for implementing the Bulk System was that all Unit Owners, etc., who currently held Individual Contracts with Company A would need to cancel those contracts.

Further Resolutions and New Rules:

In January 2015, an extraordinary general meeting of the Association passed further resolutions (these, combined with the August 2014 resolution, are referred to as "the Resolutions"). These new resolutions aimed to:

- Amend the Condominium's bylaws (規約 - kiyaku) concerning the common electrical facilities, invoking Article 65 of Japan's Condominium Ownership Act (COA), which pertains to the governance of multi-building condominium complexes.

- Establish new "Electricity Supply Rules" ("the Rules") as detailed regulations operating as part of the bylaws. These Rules explicitly stated, among other things, that Unit Owners, etc., were prohibited from receiving electricity through any method other than the new Bulk System.

The collective effect of the Resolutions and the new Rules was to create an obligation for all Unit Owners, etc., to request the cancellation of their existing Individual Contracts with Company A.

Implementation and Resistance:

In February 2015, the Association formally requested all Unit Owners, etc., who held Individual Contracts to submit the necessary documentation to initiate the cancellation of these contracts. By July 2015, all Unit Owners, etc., except for Y et al. (the defendants/appellants in the Supreme Court case), had complied. Y et al. had opposed the Resolutions from the outset and refused to submit the documentation to cancel their Individual Contracts.

X's Lawsuit for Damages:

X (the plaintiff/appellee), another unit owner, filed a lawsuit against Y et al. X alleged that Y et al.'s refusal to cancel their Individual Contracts constituted a breach of the obligations imposed by the Resolutions and/or the Rules. X claimed that this refusal was a tortious act that prevented the Condominium from switching to the Bulk System, thereby causing X to suffer financial losses in the form of unreduced electricity charges for X's private unit. X sought monetary damages from Y et al.

Lower Court Rulings:

Both the first instance court and the High Court ruled in favor of X. Their reasoning was generally:

- Electricity in the Condominium is supplied to private units via common electrical facilities.

- The Resolutions were decisions concerning the alteration or management of these common electrical facilities to enable the switch to the Bulk System.

- The cancellation of all Individual Contracts was a necessary step for this alteration/management.

- Therefore, the Resolutions, by mandating the cancellation of Individual Contracts, were valid and effective as decisions pertaining to the alteration or management of common areas, as authorized by Article 17, Paragraph 1 (alteration of common areas) or Article 18, Paragraph 1 (management of common areas) of the COA (as applied to multi-building complexes via COA Article 66).

- Consequently, Y et al.'s refusal to cancel their Individual Contracts was a breach of a validly imposed obligation and constituted a tort (不法行為 - fuhō kōi) against X.

Y et al. appealed these decisions to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Judgment

The Supreme Court, in its judgment of March 5, 2019, overturned the lower courts' decisions and dismissed X's claim against Y et al. The Court found that Y et al. were under no valid obligation to cancel their Individual Contracts.

The Supreme Court's reasoning was structured as follows:

(1) Validity of the Resolutions Regarding Cancellation of Individual Contracts (Assessed under COA Articles 17(1) or 18(1) via Article 66):

The Court acknowledged that the Resolutions to implement the Bulk System did involve elements concerning the "alteration or management of common areas" (e.g., changes to the common electrical facilities).

However, it drew a crucial distinction for the specific part of the Resolutions that obligated Unit Owners, etc., to request the cancellation of their Individual Contracts.

- The Supreme Court held that this specific obligation—to cancel a private contract for electricity supply to one's own unit—is a matter concerning "the use of private units" (専有部分の使用に関する事項 - sen'yū bubun no shiyō ni kansuru jikō).

- It is not a matter of "altering or managing common areas," even if such cancellation is a necessary precondition for a project involving common area changes.

- Therefore, this part of the Resolutions, imposing the duty to cancel, could not derive its validity from COA Article 17, Paragraph 1, or Article 18, Paragraph 1 (as applied by Article 66), which authorize general meetings to decide on common area alterations or management.

(2) Validity of the "Electricity Supply Rules" (Assessed as Bylaws under COA Article 30(1) via Article 66):

The Court then considered whether the Rules (a form of bylaw), in obligating the cancellation of Individual Contracts, could be valid under COA Article 30, Paragraph 1 (as applied by Article 66). This article allows bylaws to regulate "matters among unit owners" (in a multi-building complex, "団地建物所有者相互間の事項" - danchi tatemono shoyūsha sōgo kan no jikō) concerning the use or management of the property.

- The Supreme Court concluded that the provision in the Rules mandating the cancellation of Individual Contracts did not constitute a regulation of "matters among unit owners" within the meaning of COA Article 30, Paragraph 1. Thus, this part of the Rules was not valid as a bylaw.

- The Court provided two key reasons for this conclusion:

- The decision by a Unit Owner, etc., on whether or not to cancel their Individual Contract for electricity supply to their private unit does not, in and of itself, immediately or directly affect other Unit Owners' use of their own private units or the management of the Condominium's common areas.

- The stated purpose of switching to the Bulk System was solely to reduce electricity costs for the private units. There were no discernible circumstances indicating that the failure to make this switch would cause any actual hindrance to the normal use of private units or obstruct the proper management and maintenance of the Condominium's common areas. (The Court explicitly stated that such circumstances were not apparent from the facts of the case).

- The Court also found no other circumstances that would give rise to an obligation for Y et al. to cancel their Individual Contracts based on the Resolutions or the Rules.

(3) Conclusion on Tort Liability:

Based on the above, the Supreme Court held that:

- Y et al. were not under any valid legal obligation, arising from either the Resolutions or the Rules, to cancel their Individual Contracts with Company A.

- Therefore, their refusal to do so did not constitute a breach of duty and, consequently, could not form the basis of a tortious act against X.

X's claim for damages was accordingly dismissed.

Analysis and Broader Implications

The Supreme Court's 2019 decision is significant for defining the boundaries of a condominium management association's power to regulate matters affecting individual unit owners, particularly concerning their private contracts and the use of their exclusive spaces.

1. Limits on Collective Decision-Making Power:

The ruling clearly establishes that there are limits to what a majority vote in a general meeting or a provision in the bylaws can impose on individual unit owners. While collective decision-making is essential for managing common areas and shared interests, it does not extend to dictating all aspects of an owner's use of their private unit, especially concerning their personal contractual arrangements, unless specific legal criteria are met.

2. Strict Interpretation of "Matters Among Unit Owners":

The judgment provides a relatively strict interpretation of what constitutes "matters among unit owners" that can be validly regulated by bylaws under COA Article 30, Paragraph 1. For a matter concerning the use of a private unit to fall into this category, it appears insufficient that a particular course of action by all owners would result in a collective economic benefit (like reduced utility costs). The Supreme Court looked for a more direct and tangible link:

- Does the individual owner's action (or inaction) regarding their private unit inherently and directly impact other owners' ability to use their own private units or the association's ability to manage common areas?

- Is the proposed restriction on individual choice necessary for the fundamental adjustment of usage relationships between owners or for ensuring the proper and essential management of common areas?

In this case, the mere economic advantage of lower electricity bills for everyone was not deemed sufficient to override individual contractual autonomy when the failure to achieve that advantage did not impede the basic functioning or use of the condominium.

3. Common Area Management vs. Private Unit Use:

The Court carefully distinguished between decisions related to the common electrical facilities (which are common areas and subject to collective management decisions) and decisions related to an individual owner's private electricity supply contract. While the two are interconnected in a practical sense for a bulk supply project, the legal nature of the obligation imposed is different. Mandating a change to common facilities is within the association's purview; mandating changes to private contracts for private unit utility supply is not, unless it meets the stringent tests for regulating "matters among unit owners." The necessity of the latter for the former does not automatically validate the compulsion.

4. Relevance to "Lifeline" Contracts and Individual Choice:

This decision reinforces the principle of an individual unit owner's autonomy in choosing suppliers for essential services ("lifeline" utilities) for their private living space, especially in an era of increasing liberalization in utility markets (full retail electricity liberalization in Japan began in April 2016, though the Court's reasoning was primarily based on the COA framework). While the association can manage common utility infrastructure, it cannot easily dictate the individual owner's choice of supplier or force them to terminate existing private contracts for their own unit, absent a compelling communal need that goes beyond mere cost savings.

5. Case-Specific Considerations and Potential Openings:

It is important to note the nuanced language of the Supreme Court. The Court stated that circumstances showing that the failure to switch would "cause hindrance to the use of private units or obstruct the proper management of common areas" were "not apparent" in this case. This might suggest that if a different set of facts were presented—for instance, if an existing utility arrangement for private units was demonstrably causing severe problems for common area management or safety, or making it impossible for other owners to use their units properly—the Court might view the "necessity" for a collective solution differently.

6. Implications for Tort Claims:

The commentary surrounding this case also notes that even if a valid obligation had been imposed on Y et al. by the Resolutions or Rules, it would be a separate legal question whether their breach of that obligation would automatically constitute a tort actionable by another individual unit owner (like X) for their personal economic loss (unrealized savings). The duty breached might primarily be owed to the association, or the damages might be considered too indirect for an individual tort claim. The Supreme Court did not need to address this secondary issue as it found no valid underlying obligation.

Conclusion

The March 2019 Supreme Court judgment firmly prioritizes the autonomy of individual condominium unit owners in decisions concerning their private utility contracts, especially when the collective action sought is primarily for economic benefit and does not address a fundamental issue of common property management or essential use of private units. It clarifies that while management associations have broad powers to manage common areas, their authority to regulate the use of private units through bylaws is confined to "matters among unit owners" that have a direct and significant bearing on the shared aspects of condominium life. Forcing unit owners to terminate private contracts requires a much stronger justification than achieving cost savings for all, underscoring the protection of individual contractual freedom within the framework of condominium law. This ruling serves as important guidance for management associations considering large-scale utility changes that depend on unanimous individual action.