Condo Fee Liens and the Ticking Clock: Japanese Supreme Court on Interrupting the Statute of Limitations

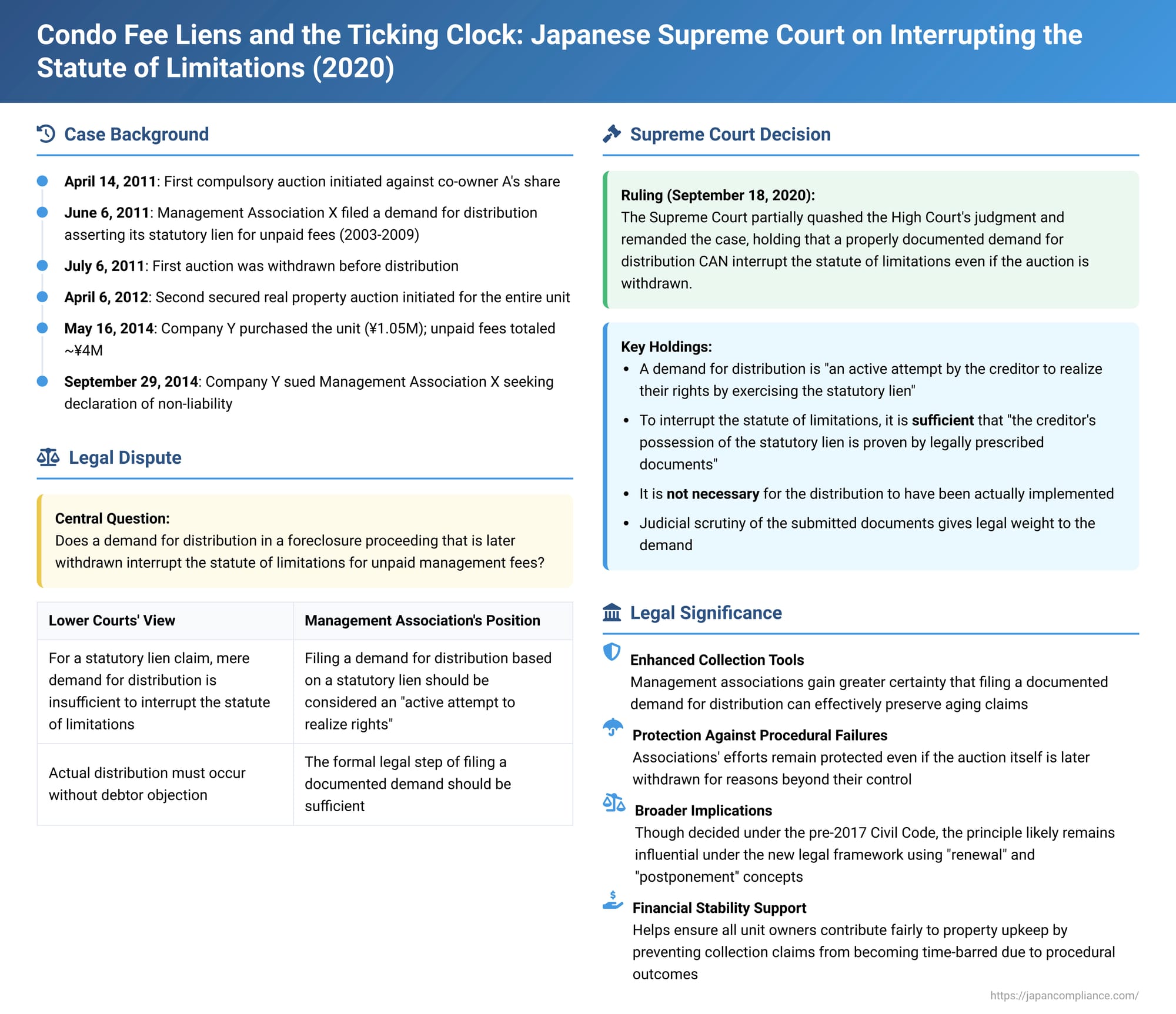

The collection of unpaid condominium management fees is a persistent challenge for management associations. These fees are vital for the upkeep and financial health of the condominium, but efforts to recover them can be hampered if the statute of limitations expires. A key question is what actions effectively "stop the clock" on these aging claims. The Supreme Court of Japan provided important clarification on this issue in a judgment delivered on September 18, 2020 (Reiwa 2 (Ju) No. 310), concerning the effect of a "demand for distribution" made in a foreclosure proceeding that was later withdrawn.

The Unpaid Fees and the Foreclosures: A Timeline

The case involved a condominium unit in Chiba City co-owned by individuals A and B, who had fallen into arrears on their management fees, repair reserve funds, and other related charges (collectively, "management fees, etc.") owed to Management Association X, the condominium's incorporated management body.

The collection efforts unfolded through two separate foreclosure proceedings:

- First Foreclosure Attempt (Compulsory Auction on Co-owner A's Share):

- On April 14, 2011, a compulsory auction (kyōsei keibai) was initiated against co-owner A's share in the unit.

- On June 6, 2011, Management Association X filed a "demand for distribution" (haitō yōkyū) in this auction. X asserted its statutory lien under Article 7, Paragraph 1 of the Condominium Ownership Act (COA) (applied mutatis mutandis by COA Article 66 for incorporated associations) for unpaid management fees that had become due between December 29, 2003, and October 27, 2009 (this specific set of fees became known as "the distribution demand claim").

- However, this compulsory auction was subsequently withdrawn on July 6, 2011.

- Property Changes Hands (Second Foreclosure - Secured Real Property Auction on the Entire Unit):

- Later, on April 6, 2012, a separate secured real property auction (tanpo fudōsan keibai) was initiated for the entire unit.

- On May 16, 2014, Company Y purchased the unit through this auction for 1.05 million yen.

- At the time of Y's purchase, the total outstanding management fees owed by the former co-owners (A and B) for the period from April 27, 2003, to April 28, 2014, amounted to approximately 4 million yen, plus accumulated late charges. Management Association X did not file a demand for distribution in this second, successful auction.

The Lawsuit:

The legal battle began when the new owner, Company Y, sued Management Association X on September 29, 2014, seeking a court declaration that Y was not liable for the substantial unpaid management fees accumulated by the previous owners. Management Association X responded on October 28, 2014, asserting the existence of the debt. On August 17, 2015, X filed a counterclaim against Y, seeking payment of all the outstanding management fees and late charges based on COA Article 8 (which generally makes subsequent purchasers liable for prior owners' unpaid fees). Company Y subsequently withdrew its main lawsuit on September 24, 2015, and invoked the statute of limitations defense against X's counterclaim for the overdue fees.

The Legal Question: Did the First (Withdrawn) Distribution Demand Stop the Clock?

Under the Japanese Civil Code in effect before the 2017 amendments (which applied to this case), claims for periodic payments like condominium management fees were generally subject to a 5-year statute of limitations (pre-2017 Civil Code Article 169). The central issue before the Supreme Court was whether Management Association X's demand for distribution, filed in the first compulsory auction (which was later withdrawn and thus resulted in no actual distribution of funds to X), had the effect of interrupting the statute of limitations for those specific fees covered by that demand.

The lower courts (Chiba District Court and Tokyo High Court) had ruled against Management Association X on this point. They held that for a claim based on a statutory lien (as opposed to a claim backed by an enforceable title of obligation like a court judgment), the mere filing of a demand for distribution was not enough to interrupt the statute of limitations. To achieve interruption, they reasoned, the process needed to have proceeded to the point of actual distribution of sales proceeds to the creditor without objection from the debtor, thereby confirming the creditor's right. Since the first auction was withdrawn before any distribution, the lower courts concluded that the statute of limitations for the distribution demand claim had not been interrupted and those fees were time-barred.

The Supreme Court's Ruling (September 18, 2020): Proof of Lien is Key

The Supreme Court disagreed with the lower courts' interpretation regarding the effect of the 2011 demand for distribution on the statute of limitations for "the distribution demand claim". It partially quashed the High Court's judgment and remanded the case for further consideration on this specific part of the claim.

The Supreme Court laid down the following core principles:

- Active Realization of Rights: The Court stated that a statutory lien under COA Article 7, Paragraph 1 (which ranks and has the effect of a general lien for common benefit expenses) is a security interest. When a creditor holding such a lien files a demand for distribution in a real property auction under the Civil Execution Act, this act "is an active attempt by the said creditor to realize their rights by exercising the said statutory lien, similar to when the said creditor initiates a secured real property auction themselves."

- Sufficient Condition for Interruption: For such a demand for distribution to have the effect of interrupting the statute of limitations (under the pre-2017 Civil Code Article 147, Item 2, which treated "attachment" as an interrupting event), it is sufficient that "the creditor's possession of the said statutory lien for the distribution demand claim is proven in the said [auction] procedure by means of legally prescribed documents" (as defined in Article 181, Paragraph 1 of the Civil Execution Act). Legally prescribed documents in this context typically include the condominium's management agreement (bylaws) and records of general meeting resolutions that form the basis for collecting management fees.

- Actual Distribution Not Required: Crucially, the Supreme Court held that it is not necessary for "the distribution, etc., to have been implemented without the debtor raising an objection to distribution, etc., concerning the said distribution demand claim." In other words, the interruption occurs when the court acknowledges the lien based on the submitted proof, regardless of whether the auction proceeds to a full payout or is later withdrawn or canceled.

Why This Matters: The Nature of Statutory Liens and Active Claims

The Supreme Court's reasoning emphasizes several key aspects:

- Proactive Assertion: A demand for distribution by a statutory lienholder is not a passive act of waiting for payment. It's an active assertion of a recognized security interest in a formal legal proceeding.

- Judicial Scrutiny: The Civil Execution Act mandates that the executing court must examine the documents submitted by the demanding creditor to verify the existence of the statutory lien. If the proof is deemed insufficient, the court is supposed to reject the demand for distribution as unlawful. This element of judicial scrutiny of the claimed lien, even without proceeding to full distribution, lends significant legal weight to the act of demanding distribution. The Court noted that this process is similar for both initiating a secured real property auction and making a demand for distribution based on such a lien.

Implications for Management Associations

This Supreme Court decision provides important and favorable clarification for condominium management associations in Japan:

- Enhanced Certainty in Collection: It offers greater certainty that taking the formal step of filing a properly documented demand for distribution in an ongoing auction can effectively interrupt the statute of limitations for the claimed delinquent fees. This is a more accessible and less costly step than initiating a full foreclosure proceeding themselves.

- Protection Even if Auction Fails: The ruling protects the association's efforts even if the auction in which they demand distribution is later withdrawn or canceled (for reasons not attributable to the invalidity of their demand itself). This counters the stricter interpretation of the lower courts, which would have nullified the interrupting effect if the auction did not culminate in a payout.

A Note on Legal Reforms and Subsequent Purchasers

- Relevance Post-Civil Code Amendments: Japan's Civil Code, particularly concerning the statute of limitations, underwent significant reforms in 2017 (which came into effect in April 2020). The old concept of "interruption" (chūdan) was largely replaced with "renewal" (kōshin) and "postponement of completion (grace period)" (kansei yūyo). For instance, actions like commencing a compulsory execution or exercising a security right now result in a postponement of the completion of the statute of limitations, and generally, upon termination of these procedures (unless due to withdrawal or cancellation for non-compliance with law), the statute of limitations is renewed. Despite these terminological and some substantive changes, legal commentary suggests that the underlying reasoning of this Supreme Court judgment—recognizing the legal effect of a duly proven demand for distribution—will likely remain influential in interpreting how such actions impact the statute of limitations under the new legal framework.

- Liability of Subsequent Purchasers: The case also operates against the backdrop of COA Article 8, which makes subsequent specific successors to the unit ownership (like Company Y) liable for management fees unpaid by previous owners. The commentary accompanying the case delves into the complex issue of whether an interruption (or renewal/postponement under the new law) of the statute of limitations against the original defaulting owner is effective against the subsequent purchaser. It is generally considered that since there is no practical way to effect an interruption against an unknown future purchaser before they acquire the property, an interruption valid against the predecessor should be assertable against the successor.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2020 decision in this case provides valuable guidance on a critical aspect of recovering unpaid condominium management fees. By holding that a properly documented demand for distribution based on a statutory lien can interrupt the statute of limitations even if the auction does not proceed to full payment, the Court has reinforced an important tool for management associations. This ruling supports their efforts to maintain financial stability and ensure that all unit owners contribute fairly to the upkeep of their shared property, by preventing claims from becoming time-barred due to procedural outcomes in foreclosure proceedings that are often beyond the association's direct control.