Concurrent Torts: Japan's Supreme Court on Joint Liability in Traffic Accident and Subsequent Medical Malpractice

Date of Judgment: March 13, 2001 (Heisei 13)

Case Reference: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench, 1998 (Ju) No. 168

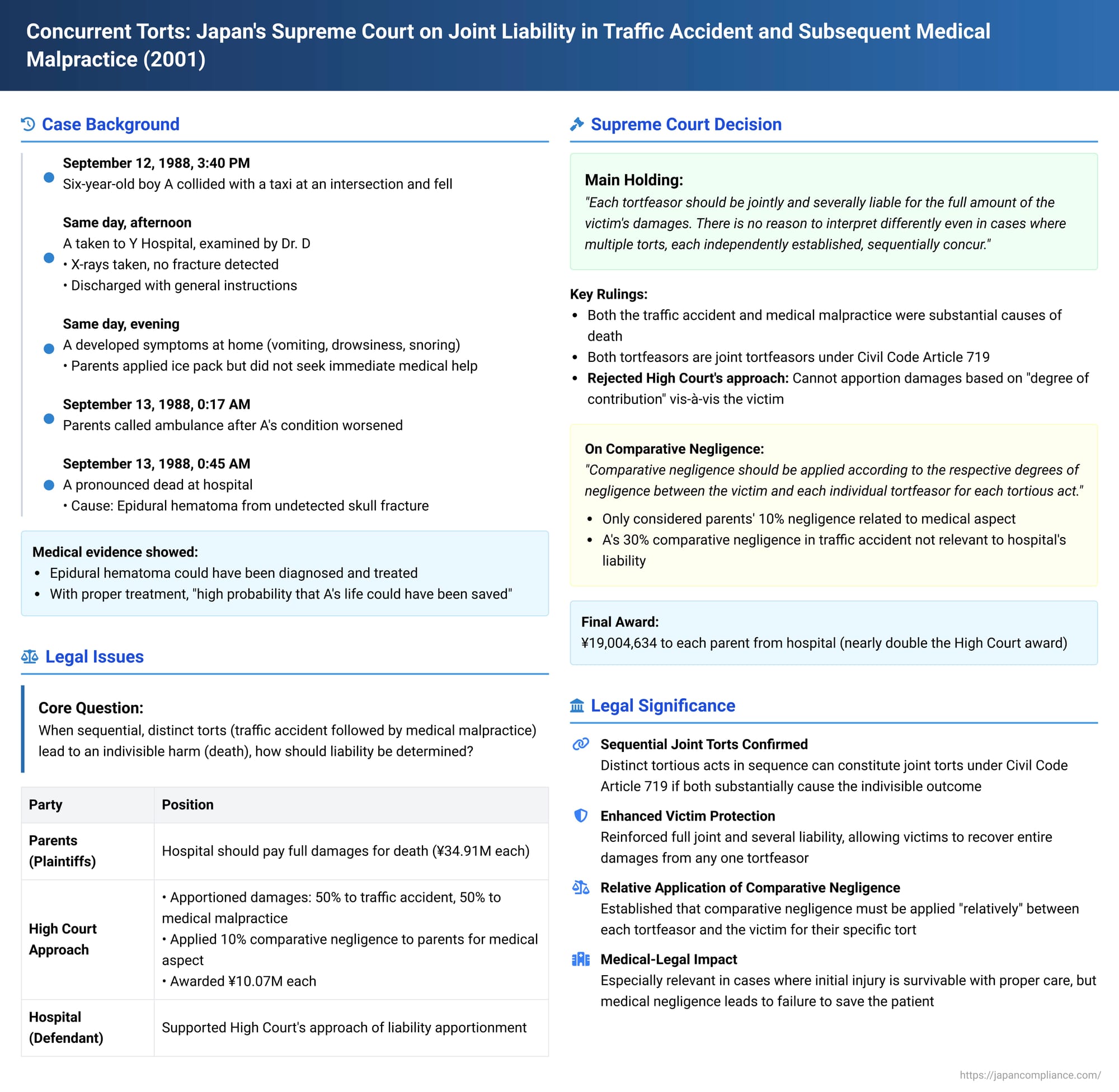

In a significant judgment delivered on March 13, 2001, the Supreme Court of Japan clarified the principles of joint tortfeasor liability in complex scenarios where an initial tort (a traffic accident) is followed by a distinct subsequent tort (medical malpractice), both contributing to a single, indivisible outcome—in this case, the death of a child. The Court affirmed that both tortfeasors could be held jointly and severally liable for the entirety of the victim's damages and provided crucial guidance on the application of comparative negligence in such sequential tort situations.

Factual Background: A Tragic Sequence of Events

The case involved A, a six-year-old boy, whose tragic death resulted from a sequence of two distinct events:

1. The Traffic Accident:

On September 12, 1988 (Showa 63), around 3:40 PM, A was riding his bicycle and entered an intersection without heeding a stop sign. He collided with a taxi driven by C, an employee of taxi company B. A fell as a result of the collision.

2. Initial Medical Examination and Discharge:

A was immediately transported by ambulance to Y Hospital, a facility operated by defendant Y (Dr. D being the hospital's representative and examining physician). Upon examination by Dr. D:

- A was conscious and lucid.

- Dr. D noted minor external injuries (slight subcutaneous bruising on the left head, minor facial abrasions).

- A reportedly described the accident as a light contact with the taxi.

- X-rays of A's head were taken, but Dr. D did not detect a skull fracture.

Based on these findings—A's clear consciousness, the seemingly minor nature of the impact as described by A, and the absence of a visible fracture on X-ray—Dr. D concluded that further investigations like a CT scan or in-hospital observation were unnecessary. He disinfected the abrasions, prescribed an antibiotic, and gave A's mother, X1 (one of the plaintiffs), general instructions: A could go to school the next day but should refrain from physical education, should return for a check-up the following day, and should come back if any unusual symptoms developed. A was then discharged and sent home.

3. Deterioration at Home:

A and his mother X1 arrived home around 5:30 PM. Shortly thereafter, A vomited and complained of drowsiness. His mother, thinking he was fatigued, put him to bed. A did not want dinner and fell asleep around 6:30 PM.

Around 7:00 PM, A began to snore, drool, and sweat profusely. His parents, X1 and X2 (A's father, also a plaintiff), noticed these symptoms and felt something was slightly unusual, but since A sometimes snored and drooled in his sleep, they did not perceive the situation as critical. They applied an ice pack around 7:30 PM and continued to let him rest.

However, A's condition worsened. Around 11:00 PM, his body temperature rose to 39°C, and he began to exhibit convulsive-like symptoms. By 11:50 PM, his snoring stopped.

4. Emergency and Death:

Realizing the gravity of the situation, X1 and X2 called for an ambulance at approximately 0:17 AM on September 13. The ambulance arrived around 0:25 AM, by which time A had no palpable pulse and had stopped breathing. He was transported to a different hospital (Miyoshi Kosei Hospital in the judgment text, but the initial treatment hospital was Y Hospital) but was pronounced dead at 0:45 AM. This sequence, from the failure of adequate diagnosis/treatment at Y Hospital to A's death, was termed "the present medical accident."

5. Cause of Death – Epidural Hematoma:

An autopsy revealed that A's death was caused by an epidural hematoma (a collection of blood between the skull and the dura mater, the brain's outer lining). This hematoma resulted from damage to an epidural artery, which in turn was caused by an external linear skull fracture that Dr. D had failed to detect on the initial X-rays.

Medical evidence presented in the case explained that epidural hematomas can sometimes occur even without an obvious fracture and are often characterized by an initial "lucid interval" where the patient appears relatively well. This can be followed by symptoms like headache, vomiting, drowsiness, and deteriorating consciousness. If an epidural hematoma progresses to cause severe brain compression and decerebrate rigidity (a sign of severe brainstem injury), the chances of survival decrease dramatically, and even if life is saved, there is a high risk of severe permanent neurological disabilities. However, if an epidural hematoma is diagnosed and surgically evacuated (the blood clot removed) early, the prognosis is generally good, with a high probability of survival and recovery.

The facts established that A's vomiting shortly after returning home and his subsequent drowsiness were signs of increasing intracranial pressure from the developing hematoma. By the time convulsive symptoms appeared, he was likely in a state of decerebrate rigidity, and by the time his breathing stopped, treatment was likely futile. The appropriate medical response for a child with a head injury like A's, even with initially clear consciousness, would have included either in-hospital observation or very specific instructions to the parents about monitoring for warning signs of intracranial bleeding (like persistent vomiting, increasing drowsiness, changes in behavior) and the critical need for immediate medical attention if such signs appeared. Dr. D's general instructions were found to be insufficient.

The Legal Claim

A's parents, X1 and X2, sued Y (the operator of Y Hospital) for damages. They claimed approximately 34.91 million yen each, alleging that the medical malpractice of Dr. D (for whom Y was vicariously liable) in failing to properly diagnose A's condition, failing to conduct necessary observations or tests (like a CT scan), and failing to provide adequate instructions to the parents, led to A's death.

Lower Court Proceedings: Joint Tortfeasors and a Novel Approach to Apportioning Liability

- First Instance (Urawa District Court, Kawagoe Branch): The trial court found that both the taxi driver C (and by extension, the taxi company B) and Dr. D (and by extension, Y Hospital) were negligent. It held them to be joint tortfeasors under Article 719 of the Civil Code. Consequently, it found Y Hospital liable for the full amount of damages determined, which was approximately 22.01 million yen for each parent. Y Hospital appealed this decision.

- High Court (Tokyo High Court): The High Court also found that the actions of the taxi driver and Dr. D constituted joint torts leading to A's death. However, it introduced a novel approach to apportioning liability between the joint tortfeasors and applying comparative negligence:

- Reasoning for Apportionment: The High Court argued that in cases like this, where there are multiple, distinct tortious acts (the traffic accident and the subsequent medical malpractice) that are sequential, different in nature and fault structure, and where comparative negligence on the part of the victim (or those connected to the victim) might apply differently to each tortious act, it is appropriate to:

- Determine the victim's total damages.

- Assess the "degree of contribution" (寄与度 - kiyodo) of each tortious act to the overall damage.

- Apportion the total damages according to this degree of contribution.

- Apply comparative negligence separately to each tortfeasor's apportioned share of the damages.

- Application to the Case:

- The High Court assessed the contribution of the traffic accident to A's death at 50%.

- It assessed the contribution of Dr. D's medical malpractice to A's death at 50%.

- It found that A's parents (X1 and X2) were comparatively negligent by 10% in relation to the medical malpractice aspect, due to their delay in seeking further medical attention after A returned home and his symptoms developed (this negligence was related to their observation and protection duties for A after he was discharged by Dr. D).

- Damages Calculation by High Court: Based on this, the High Court held Y Hospital liable for 50% of the total damages. This 50% share was then further reduced by the parents' 10% comparative negligence. This resulted in an award of approximately 10.07 million yen for each parent from Y Hospital.

The plaintiffs, X1 and X2, appealed this High Court decision to the Supreme Court, challenging the apportionment of damages and the application of comparative negligence.

- Reasoning for Apportionment: The High Court argued that in cases like this, where there are multiple, distinct tortious acts (the traffic accident and the subsequent medical malpractice) that are sequential, different in nature and fault structure, and where comparative negligence on the part of the victim (or those connected to the victim) might apply differently to each tortious act, it is appropriate to:

The Supreme Court's Decision (March 13, 2001)

The Supreme Court overturned the High Court's judgment concerning the apportionment of damages and the method of applying comparative negligence. It then rendered its own judgment, increasing the amount of damages payable by Y Hospital.

1. Joint Tortfeasor Liability (Civil Code Article 719) and Rejection of Apportionment Vis-à-vis the Victim:

- Indivisible Result and Causal Link: The Supreme Court first established that A sustained an injury in the traffic accident (the head trauma leading to the epidural hematoma) which, if left undiagnosed and untreated, would ultimately lead to death. However, if A had received "ordinarily expected appropriate observation" at Y Hospital after the accident, and if the resulting intracranial bleeding had been detected early and treated properly, "there was a high degree of probability that A's life could have been saved."

- Both Acts Were Substantial Causes: Therefore, the Court concluded that both the traffic accident and the subsequent medical malpractice (Dr. D's failure in diagnosis, observation, and instruction) were substantial causes that led to the single, indivisible result of A's death. Each act had a "considerable causal relationship" (相当因果関係 - sōtō inga kankei) with the death.

- Joint Tort Established: Consequently, the negligent driving in the traffic accident and the negligent medical acts constituted joint torts under Article 719 of the Civil Code.

- No Apportionment of Liability to the Victim: The Supreme Court firmly rejected the High Court's approach of apportioning the victim's total damages based on the respective "degrees of contribution" of each tortfeasor when determining each tortfeasor's liability to the victim. It stated: "Therefore, each tortfeasor should be jointly and severally liable for the full amount of the victim's damages. There is no reason to interpret differently even in cases like the present, where multiple torts, each independently established, sequentially concur. It is appropriate to understand that, in relation to the victim, it is not permissible to apportion the victim's damages based on the degree of contribution of each tortfeasor to the occurrence of the result and thereby limit the amount of damages each tortfeasor should be liable for."

- Rationale for Full Liability: The Court reasoned that allowing such apportionment would contravene the clear provision of Article 719, which establishes joint and several liability to ensure victim protection (allowing the victim to recover the full amount from any one of the joint tortfeasors). Apportioning damages vis-à-vis the victim would effectively negate this joint and several liability and would be contrary to the principle of fairness in distributing the burden of loss.

2. Application of Comparative Negligence (過失相殺 - kashitsu sōsai):

- "Relative" Application of Comparative Negligence: The Supreme Court clarified how comparative negligence should be applied in such cases of sequential, distinct joint torts: "The present case involves two tortious acts—the traffic accident and the medical malpractice—which are distinct in terms of tortfeasors and infringing acts, and where the nature of the victim's (and tortfeasor's) negligence may also differ for each tort. Comparative negligence is a system to achieve relative fairness in burden-sharing between the tortfeasor and the victim based on their respective degrees of negligence for the damages caused by the tort. Therefore, even in joint torts like the present case, comparative negligence should be applied according to the respective degrees of negligence between the victim and each individual tortfeasor for each tortious act. It is not permissible to take into account the victim's degree of negligence in relation to another tortfeasor when applying comparative negligence for a specific tort."

- Application to the Current Case: This meant that when determining Y Hospital's liability, only the comparative negligence of A's parents (X1 and X2) specifically related to the medical malpractice aspect (their 10% negligence in monitoring A after discharge) should be considered. The comparative negligence of A himself in relation to the traffic accident (which lower courts had assessed at 30%) would be relevant only when determining the liability of the taxi driver/company, not Y Hospital.

- Recalculation of Damages: The Supreme Court then recalculated the damages owed by Y Hospital. It started with the total assessed damages for A's death (excluding attorney's fees initially, totaling 40,788,076 yen). It applied the 10% comparative negligence of the parents (reducing the sum to 36,709,268 yen). From this, it deducted 500,000 yen that the parents had already received from the taxi company (as part of funeral expenses). Finally, it added a standard amount for attorney's fees (1,800,000 yen). This resulted in a total liability for Y Hospital of 38,009,268 yen, to be divided equally between the two parents (19,004,634 yen each). This was significantly higher than the High Court's award.

Analysis and Implications: Strengthening Victim Protection in Concurrent Tort Scenarios

The Supreme Court's March 13, 2001, decision is a landmark in Japanese tort law, particularly for cases involving a sequence of distinct negligent acts leading to a single, indivisible harm.

- Affirmation of Joint Tort Liability for Sequential, Distinct Acts: The ruling confirms that separate and distinct tortious acts, such as a traffic accident causing an initial injury and subsequent medical malpractice that fails to prevent death or worsens the condition, can be treated as joint torts under Civil Code Article 719 if both acts are substantial causes of the final, indivisible outcome.

- Rejection of Apportioning Primary Liability to the Victim: A crucial principle established by this case is the firm rejection of any attempt to apportion the victim's total damages among joint tortfeasors based on their perceived "degrees of contribution" when determining what each tortfeasor owes to the victim. Each joint tortfeasor remains liable for the entire damage. The issue of apportioning the financial burden among the tortfeasors themselves (e.g., in a subsequent contribution claim by one tortfeasor against another) is a separate matter and does not affect their primary, full liability to the injured party.

- Clarification of "Relative" Comparative Negligence: The decision provides clear guidance that comparative negligence must be applied "relatively." That is, when assessing the liability of a specific tortfeasor (e.g., the hospital), only the victim's (or related parties') negligence specifically pertaining to that tortfeasor's wrongful act (e.g., the medical malpractice) should be considered for reducing that tortfeasor's liability. The victim's negligence concerning a different tortious act by a different party is not to be factored into this specific calculation.

- Enhanced Victim Protection: The overall impact of this judgment is to significantly strengthen the position of victims in cases of multiple, concurring torts. By upholding the principle of joint and several liability for the full damage and by ensuring a relative application of comparative negligence, the Supreme Court reinforced the protective aims of Article 719 of the Civil Code. Victims are entitled to seek full compensation from any one of the responsible parties, simplifying their path to redress.

- Scope and Context: As legal commentators have noted, this ruling is particularly applicable to situations where an initial injury (e.g., from a traffic accident) is survivable with appropriate medical care, but subsequent medical negligence directly leads to a failure to save the patient, and both acts are causally linked to the death. Its application to scenarios with more attenuated causal links or where the medical negligence results in a "loss of chance" rather than directly causing the final outcome might require further nuanced consideration.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's judgment in the "Traffic Accident and Medical Malpractice Concurrence Case" is a vital precedent in Japanese tort law. It robustly affirms the principle of full joint and several liability of tortfeasors towards the victim when their distinct acts concurrently lead to an indivisible harm. Furthermore, its clarification on the "relative" application of comparative negligence ensures a fairer and more victim-protective approach in complex, multi-actor tort scenarios. This ruling provides essential clarity for practitioners and lower courts dealing with the intricate legal challenges that arise when separate acts of negligence combine to produce a single tragic result.