Japan’s Supreme Court Upholds Compulsory National Health Insurance (1958)

TL;DR

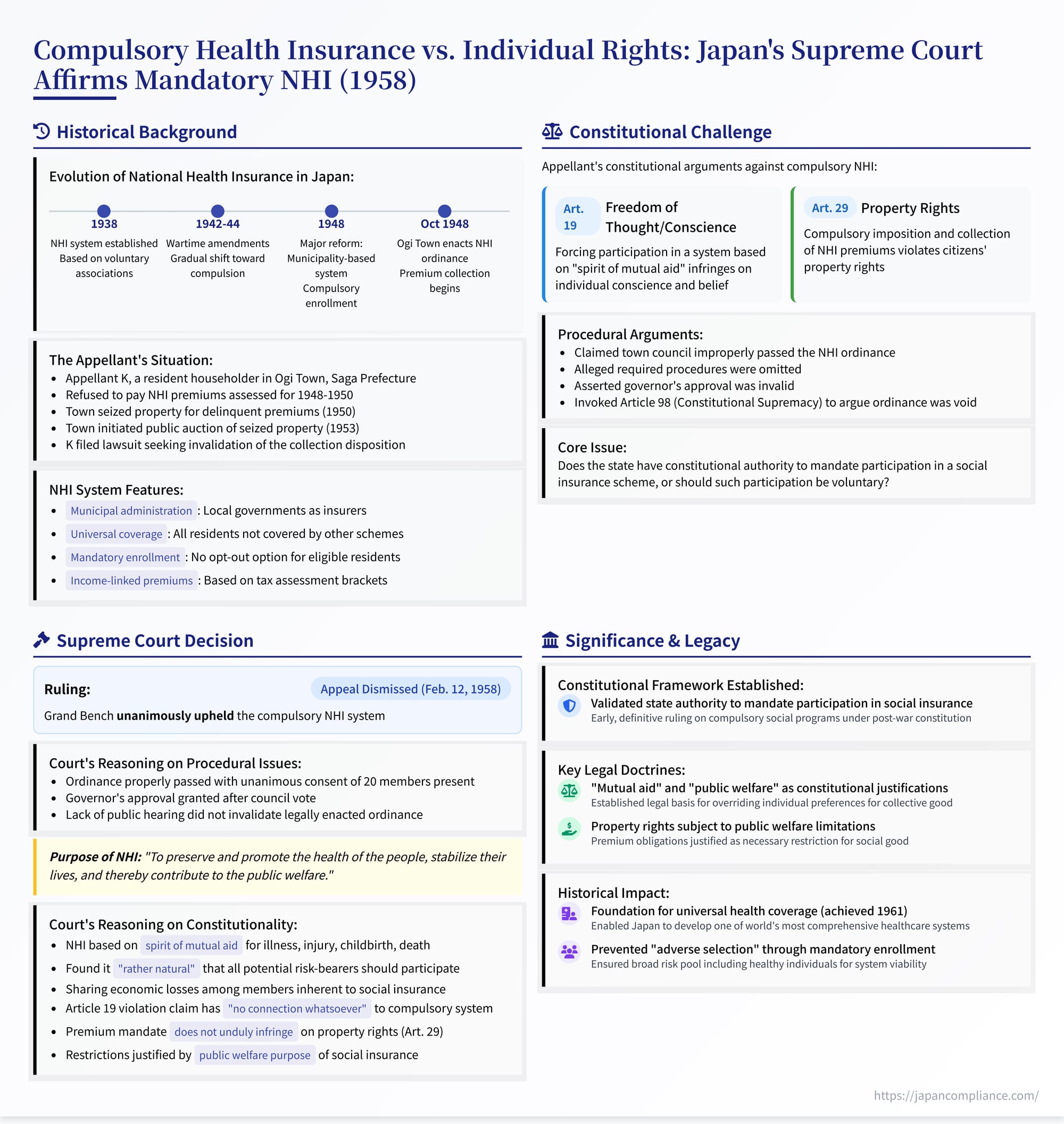

In 1958 the Japanese Supreme Court’s Grand Bench ruled that municipalities can mandate National Health Insurance enrollment and premiums without violating constitutional rights. Citing public welfare and mutual aid, the Court rejected claims under Articles 19 and 29 and confirmed the procedural validity of Ogi Town’s ordinance—paving the way for Japan’s universal health coverage.

Table of Contents

- Background: From Voluntary Associations to Municipal Compulsory Insurance

- The Appellant’s Challenge: Compulsion and Non‑Payment

- The Supreme Court’s Decision: Compulsory NHI Upheld

- Significance and Analysis

- Conclusion

The establishment of universal health coverage systems often involves a fundamental policy choice: should participation be voluntary or compulsory? While voluntary systems might seem more aligned with individual liberty, they face significant challenges related to adverse selection and ensuring a broad, stable risk pool. Compulsory systems, conversely, ensure universal participation necessary for social insurance principles like risk-spreading and mutual aid but inevitably raise questions about individual autonomy and property rights. Japan's journey towards universal health coverage saw a pivotal moment addressed in a 1958 Supreme Court Grand Bench decision. This case, formally the Case Concerning Request for Confirmation of Invalidity of Disposition for Failure to Pay Taxes (Supreme Court, Grand Bench, Showa 30 (O) No. 478, Feb. 12, 1958), dealt with the constitutional validity of making enrollment and premium payment for the newly reorganized National Health Insurance (NHI) system mandatory for residents.

Background: From Voluntary Associations to Municipal Compulsory Insurance

Japan's National Health Insurance (国民健康保険, Kokumin Kenkō Hoken or Kokuho) system has undergone significant evolution. Initially established in 1938, it largely relied on voluntarily formed NHI Associations (kumiai) based in municipalities or occupational groups, with enrollment often being voluntary for eligible individuals (like householders).

During World War II, driven by national health and mobilization goals, amendments in 1942 strengthened the push towards broader coverage, allowing compulsory establishment of associations and mandating enrollment for all eligible persons in certain designated associations. The Ogi Town NHI Association in Saga Prefecture, where the appellant resided, became subject to this compulsory enrollment system in November 1944.

The post-war period saw major reforms. The National Health Insurance Act underwent a significant revision in 1948 (Act No. 70 of Showa 23). This reform shifted the primary responsibility for administering NHI from associations to municipalities (cities, towns, villages), establishing them as the public insurers. Crucially, the revised law stipulated that residents within a municipality's area (specifically, householders and their dependents) would become insured persons under the municipality's NHI program (with exceptions for those covered by employee-based health insurance, certain mutual aid associations, or those poor enough to be exempt from local taxes). This effectively established the principle of compulsory enrollment (kyōsei kanyū) at the municipal level for those not otherwise covered.

Following this 1948 reform, the Town of Ogi (the appellee) enacted its own municipal NHI Ordinance (jōrei) in October 1948. The ordinance was passed unanimously by the town council members present and subsequently approved by the prefectural governor, formally launching the town-run, compulsory NHI program.

The ordinance (Article 5) mandated that all householders and their dependents residing in the town were insured persons, subject to the standard exceptions. It also stipulated (Article 31) that insured householders were obligated to pay NHI premiums (hokenryō), with the amount determined based on their assessment bracket for the Town Inhabitant's Tax (chōmin-zei), effectively linking premiums to an indicator of ability to pay.

The Appellant's Challenge: Compulsion and Non-Payment

The appellant, K, a resident householder in Ogi Town, was assessed NHI premiums by the town for the fiscal years 1948, 1949, and 1950 based on the ordinance. K failed to pay these premiums.

Consequently, in 1950, the Town of Ogi initiated collection procedures for the delinquent premiums, plus penalty fees. It seized K's movable property and telephone subscription rights. In October 1953, the town notified K of its intention to proceed with a public auction of the seized property to satisfy the unpaid premiums. This enforcement action, known as a disposition for failure to pay taxes (tainō shobun – the term used even for compulsory premium collection), prompted K to file a lawsuit.

K sought a court declaration confirming the invalidity of the town's non-payment disposition. His challenge was multi-faceted, attacking both the procedural validity of the ordinance and the fundamental constitutionality of the compulsory NHI system itself:

- Procedural Invalidity: K claimed the Ogi Town NHI Ordinance was improperly enacted. He alleged that certain council members were absent during the vote (invalidating the resolution) and that required procedures like a public hearing were omitted, arguing it was passed despite widespread opposition from residents. He also claimed the prefectural governor's approval was granted before the town council had actually voted on the ordinance, rendering the approval invalid.

- Unconstitutionality of Compulsory NHI: K's core constitutional argument was that the NHI system, inherently flawed, should be voluntary. He argued that forcing residents to join and pay premiums violated fundamental rights under the post-war Constitution of Japan:

- Article 19 (Freedom of Thought and Conscience): K implied that compelling participation in a system based on a "spirit of mutual aid" infringed upon individual conscience or belief, arguing that joining such a system should be a matter of free will.

- Article 29, Paragraph 1 (Property Rights): He argued that the compulsory imposition and collection of NHI premiums constituted an unjustified infringement upon citizens' property rights.

- Article 98 (Supremacy of the Constitution): He cited this article to argue that the ordinance, being unconstitutional, was void.

The Saga District Court and the Fukuoka High Court both ruled against K, upholding the validity of the ordinance and the town's collection actions. K then appealed to the Supreme Court of Japan, bringing the constitutional challenge before the Grand Bench.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Compulsory NHI Upheld

The Supreme Court Grand Bench, in its decision on February 12, 1958, unanimously dismissed K's appeal, thereby affirming the constitutionality of the compulsory municipal NHI system and the related premium obligations.

1. Reasoning on Procedural and Approval Issues:

The Court quickly disposed of the procedural challenges. It reviewed the evidence presented in the lower courts (including witness testimony regarding the timeline) and found no reason to overturn the factual findings that:

- The Ogi Town NHI Ordinance was properly passed by the town council on October 30, 1948, with the unanimous consent of the 20 members present (out of 26 total members). There was insufficient evidence to support K's claim that specific members were absent.

- The prefectural governor's approval was granted after the council's vote (around November 2, 1948), even if the approval document might have been dated retroactively to October 30th.

- The lack of a public hearing or alleged public opposition did not invalidate a legally enacted ordinance passed by the representative town council and approved by the governor.

Therefore, the ordinance was deemed procedurally valid.

2. Reasoning on Constitutionality (Articles 19 & 29):

The Court then addressed the fundamental constitutional challenge to the compulsory nature of the NHI system.

- Purpose of NHI: The Court began by defining the purpose of NHI. It stated that NHI operates based on the spirit of mutual aid and mutual support (sōfu kyōsai no seishin) to provide insurance benefits concerning illness, injury, childbirth, or death. The ultimate objective is clearly to preserve and promote the health of the people, stabilize their lives, and thereby contribute to the public welfare (kōkyō no fukushi).

- Justification for Compulsory Enrollment: Given this public welfare objective and the nature of insurance based on mutual aid, the Court found it "rather natural" (mushiro tōzen) that the pool of insured persons should ideally encompass all individuals potentially subject to the insured risks (i.e., residents). This broad participation is necessary to effectively disperse risk across the community.

- Justification for Compulsory Premiums: Furthermore, the Court stated that it "requires no argument" (ron o matanai) that based on the nature of mutual aid insurance, the economic losses individuals suffer due to insured events (illness, injury, etc.) should be shared among the members of the insurance pool (the participants). Therefore, requiring insured individuals – specifically, householders deemed capable of contributing, with assessments linked to ability to pay via tax brackets – to pay premiums is inherent to the system's mutual aid principle.

- No Violation of Constitutional Rights: Based on these justifications, the Court concluded that the Ogi Town NHI Ordinance, legally enacted by elected representatives and approved by the governor, did not unconstitutionally infringe upon individual rights by establishing compulsory enrollment and mandating premium payments:

- Article 19 (Freedom of Thought and Conscience): The Court stated that the compulsory system clearly had "no connection whatsoever" (nan-ra kakawari nai) to Article 19. The obligation to join and pay premiums was viewed as a matter of social organization for public welfare, not an imposition on belief or conscience.

- Article 29(1) (Property Rights) and Other Freedoms: The Court held that the compulsory enrollment and premium obligation did not constitute an undue infringement (yue naku shingai suru mono) on property rights or other constitutional freedoms. The imposition serves the legitimate public welfare purpose inherent in the social insurance system.

- Conclusion: The Court rejected K's constitutional arguments as unfounded.

Significance and Analysis

The 1958 Ogi Town Grand Bench decision stands as a foundational pillar in Japanese social security law, providing crucial judicial validation for the compulsory nature of the National Health Insurance system in the post-war constitutional era.

- Affirmation of Compulsory Social Insurance: This ruling was one of the earliest and most definitive statements from the highest court affirming the state's power, acting through local governments and representative assemblies, to mandate participation in social insurance schemes like NHI for the sake of public welfare. It established that such compulsion is constitutionally permissible.

- "Mutual Aid" and "Public Welfare" as Justification: The Court heavily relied on the concepts of "mutual aid/mutual support" (sōfu kyōsai) and "public welfare" (kōkyō no fukushi) as the constitutional justifications for overriding individual preferences regarding insurance enrollment and imposing financial obligations (premiums). This rationale became central to justifying various compulsory social programs in Japan.

- Limited Scope of Article 19: The Court gave short shrift to the Article 19 (freedom of thought and conscience) claim, viewing the NHI system as essentially unrelated to matters of conscience. While some might argue that forced participation in a system embodying a specific "spirit" (mutual aid) could potentially conflict with individual beliefs (e.g., extreme individualism or specific religious objections), the Court saw it purely as a practical mechanism for social organization and risk management.

- Property Rights Subject to Public Welfare: The ruling confirmed that property rights under Article 29(1) are not absolute and can be restricted for the public welfare. The compulsory payment of NHI premiums was deemed a justifiable restriction necessary to fund a system serving the vital public goal of ensuring access to healthcare and stabilizing lives.

- Basis for Future Developments: By upholding the fundamental principle of compulsory NHI, this decision laid the groundwork for the eventual achievement of universal health coverage in Japan (formalized in 1961) and provided the constitutional underpinning for subsequent developments and refinements of the system, including later debates about premium levels, calculation methods, and exemptions (as seen in the 2006 Asahikawa case).

- Economic Rationales: While the Court focused on "mutual aid" and "public welfare," economic rationales also support compulsory health insurance. As noted by commentators reviewing related cases, mandatory enrollment prevents "adverse selection" – the phenomenon where only individuals with high health risks choose to join voluntary schemes, making them financially unsustainable. Compulsion ensures a broad risk pool including healthy individuals, which is essential for the viability of insurance based on risk-spreading.

Conclusion

The 1958 Ogi Town decision by the Supreme Court Grand Bench provided early and crucial constitutional validation for Japan's shift towards a compulsory, municipally-administered National Health Insurance system. By emphasizing the principles of mutual aid and public welfare inherent in social insurance, the Court concluded that mandating resident enrollment and requiring premium payments based on ability to pay did not violate fundamental rights, including freedom of thought and conscience (Article 19) or property rights (Article 29). This landmark ruling affirmed the legislature's power to establish compulsory social insurance schemes as a legitimate means of promoting the health and stability of the populace under the post-war Constitution.

- When a Lie Becomes a Crime: Japan's Landmark Case on Lying for an Arrested Friend

- The Scapegoat Gambit: A Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Aiding an Arrested Criminal's Escape

- Memory vs. Truth: How Japan's High Court Defined Perjury Over a Century Ago

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare – National Health Insurance Overview