Competition Law Meets Data Protection: What the CJEU’s Meta Ruling Means for GDPR & Dominance Cases

TL;DR

- The CJEU’s 4 July 2023 Meta ruling lets competition authorities factor GDPR breaches into abuse-of-dominance cases while stressing cooperation with DPAs.

- It sharply narrows “contractual necessity” / “legitimate interests” for advertising data-combination and raises the bar for valid consent by dominant platforms.

- Global companies must re-audit cross-service data flows, offer real opt-outs, and prepare for joint NCA-DPA scrutiny.

Table of Contents

- Background: The German Cartel Office vs. Facebook (Meta)

- The Referral to the CJEU

- The CJEU's Judgment: Key Holdings

- Implications for Digital Platforms and Enforcement

- Conclusion

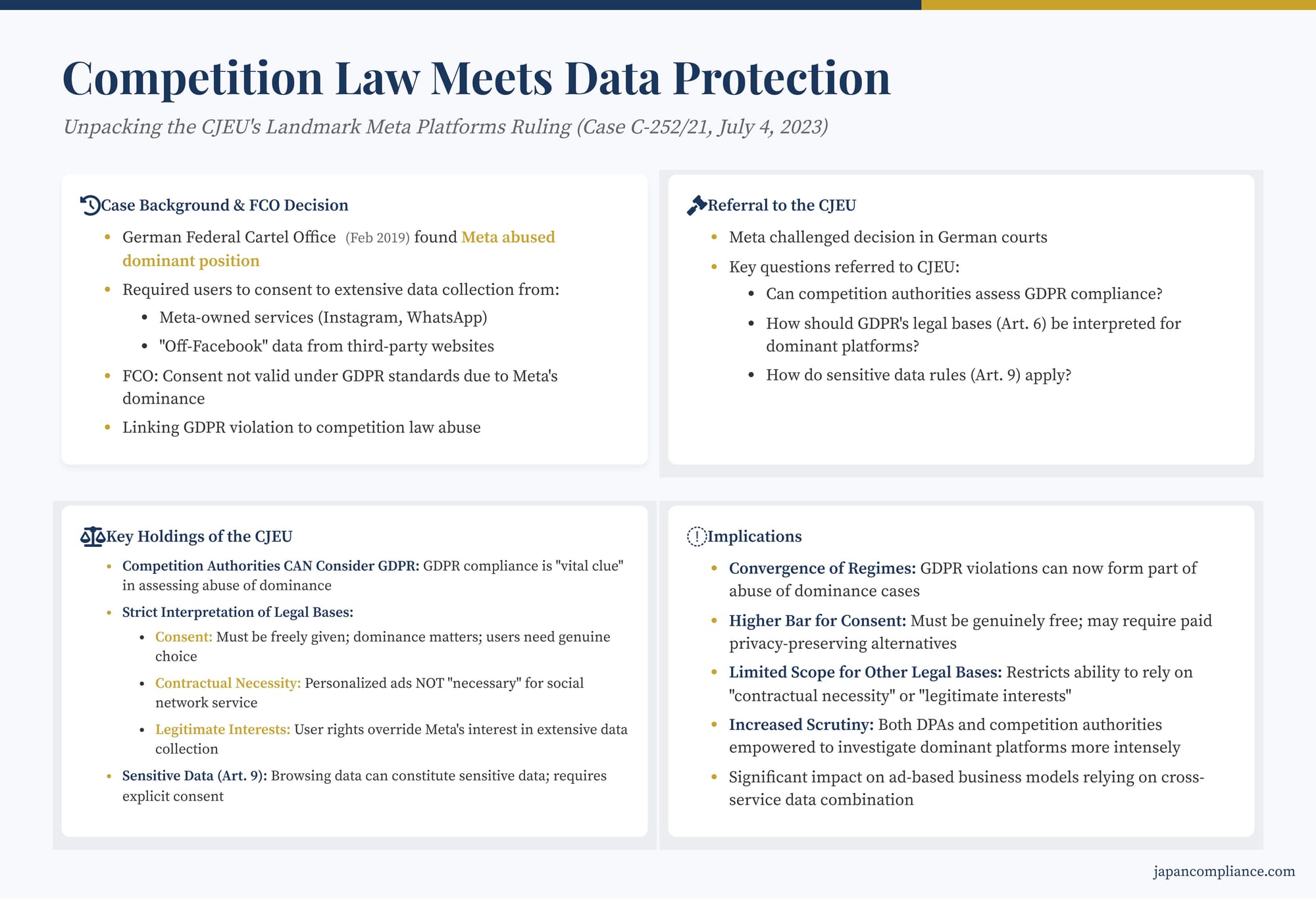

The intersection of data protection and competition law is a critical battleground in the digital economy. How much personal data can dominant online platforms collect and combine, and under what legal justifications? Can competition authorities step in when data practices raise concerns under data protection law like the EU's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)? These questions were central to a landmark ruling by the Grand Chamber of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) on July 4, 2023 (Case C-252/21, Meta Platforms and Others). Stemming from a challenge to a German competition authority decision, the judgment has profound implications for large digital platforms, personalized advertising, and the enforcement powers of regulators in Europe.

Background: The German Cartel Office vs. Facebook (Meta)

The case originated with a decision by Germany's Federal Cartel Office (Bundeskartellamt - FCO) in February 2019. The FCO found that Meta (then Facebook) had abused its dominant position in the German market for social networks.

The FCO's focus was on Meta's terms of service, which required users of the core Facebook.com platform to agree to the company collecting their data not only from their direct use of Facebook but also extensively from:

- Other Meta-owned services (like Instagram, WhatsApp).

- Third-party websites and apps ("off-Facebook" data) using embedded Meta tools (e.g., "Like" buttons, Facebook Login, Facebook Pixel analytics).

Crucially, the FCO found that Meta then combined all this data and linked it to individual users' Facebook accounts, primarily for the purpose of building detailed user profiles and delivering highly personalized advertising.

The FCO concluded this constituted an exploitative abuse of dominance under German competition law. A key part of its reasoning was that the "consent" obtained through the terms of service was not valid under GDPR standards. Given Facebook's dominance, users lacked a genuine choice; they had to agree to this extensive data collection and combination regime to access the essential social networking service. This invalid consent, according to the FCO, demonstrated the unfairness and exploitative nature of the terms imposed on users, thereby constituting an abuse of dominance. This decision was groundbreaking for directly linking a GDPR violation (lack of valid consent) to a competition law infringement.

The Referral to the CJEU

Meta challenged the FCO's decision in the German courts. The Düsseldorf Higher Regional Court, facing complex questions about the interplay between the two legal regimes, suspended the proceedings and asked the CJEU for a preliminary ruling on several key issues, including:

- Can a national competition authority (NCA) assess whether a company's data processing practices comply with GDPR when investigating an abuse of dominance?

- How should GDPR's legal bases for processing (Article 6(1)) – particularly consent, contractual necessity, and legitimate interests – be interpreted in the context of a dominant social network processing extensive on-platform and off-platform data for personalized advertising?

- How should GDPR's rules on processing sensitive personal data (Article 9) apply in this context?

The CJEU's Judgment: Key Holdings

The CJEU's Grand Chamber delivered a comprehensive judgment addressing these points:

1. Competition Authorities Can Consider GDPR Compliance:

The Court ruled decisively that NCAs are permitted to consider an undertaking's compliance with regulations outside competition law, including the GDPR, when determining whether its conduct constitutes an abuse of a dominant position under Article 102 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU).

- Rationale: Compliance with data protection rules like GDPR is a "vital clue" in assessing whether a dominant company's actions constitute normal "competition on the merits" or are exploitative/exclusionary. In the digital economy, access to and use of personal data are crucial parameters of competition; ignoring data protection rules would ignore this reality and potentially undermine effective competition enforcement.

- Limitations & Cooperation: However, the CJEU clarified that NCAs do not become substitute data protection authorities (DPAs). Their assessment of GDPR compliance is incidental to the competition law analysis, not enforcement of GDPR for its own sake. NCAs must cooperate sincerely with the competent DPAs and cannot depart from prior DPA decisions on the same conduct, though they can draw their own conclusions in the absence of such decisions.

2. Strict Interpretation of GDPR's Legal Bases (Art. 6(1)) for Processing:

The CJEU provided crucial interpretations of the primary legal bases Meta sought to rely on for its extensive data processing:

- Consent (Art. 6(1)(a)):

- Dominance does not automatically preclude valid consent, but it is a significant factor in assessing whether consent was truly freely given. The dominant undertaking bears the burden of proof.

- For consent to be free, users must have the ability to refuse consent for non-essential processing (like combining off-Facebook data for personalized ads) without being forced to cease using the core service entirely. The Court suggested that offering an equivalent alternative service, potentially for an appropriate fee, that doesn't involve such data processing might be necessary to ensure genuine freedom of choice.

- Given the different types of data processing involved (on-Facebook data, data from other Meta services, off-Facebook data), separate consents for distinct operations might be required to meet the GDPR's requirement for specific and informed consent. Bundling consent for vastly different processing activities is problematic.

- Contractual Necessity (Art. 6(1)(b)):

- This legal basis must be interpreted strictly. Processing is "necessary" only if it is objectively indispensable for performing the core objective of the contract that the user actually signed up for.

- Personalized advertising is generally not considered objectively indispensable for providing social networking services. The service can function without it, even if personalization enhances user experience or funds the "free" service. An alternative without such personalization is conceivable.

- Ensuring "consistency" or "seamless use" across different Meta services (e.g., using WhatsApp data to personalize Facebook) is generally not necessary for the performance of the specific contract for the Facebook service itself.

- Legitimate Interests (Art. 6(1)(f)):

- This requires balancing the controller's interests against the fundamental rights and freedoms of the data subject, taking their reasonable expectations into account.

- While personalized advertising can be a legitimate interest for a platform funded by advertising, the CJEU found that users of a "free" social network do not reasonably expect the operator to process their personal data—especially sensitive data or extensive data collected outside the platform (off-Facebook data)—for that purpose without their explicit consent.

- Given the extraordinary scope of Meta's data collection (potentially monitoring nearly all online activity) and its significant impact on users (creating a feeling of constant surveillance), the Court concluded that the users' fundamental rights override Meta's commercial interest in this specific context. Therefore, Meta could not rely on legitimate interests as a legal basis for this extensive processing without valid consent.

3. Heightened Requirements for Processing Sensitive Data (Art. 9):

The CJEU also clarified rules around sensitive data:

- Visiting websites or apps related to sensitive topics (e.g., health, religion, sexual orientation, political opinions) and interacting with them (liking, commenting, entering data) can constitute processing of sensitive data by Meta if it links this information to a user's profile.

- The general prohibition on processing sensitive data (Art. 9(1)) applies. The narrow exception for data "manifestly made public by the data subject" (Art. 9(2)(e)) requires an explicit act by the user making their data public (like choosing specific privacy settings), not simply Browse habits or clicking buttons on third-party sites. This makes it very difficult for platforms to process inferred sensitive data without explicit consent (Art. 9(2)(a)).

Implications for Digital Platforms and Enforcement

The Meta Platforms ruling has significant consequences:

- Convergence of Competition and Data Protection: It solidifies the link between the two fields. GDPR violations can now more clearly form part of an abuse of dominance case against powerful digital players. Expect NCAs to pay closer attention to data practices.

- Higher Bar for Consent: Dominant platforms must ensure consent is genuinely free, specific, informed, and unambiguous, particularly for processing beyond core service delivery. The potential need for paid, privacy-preserving alternatives is a major implication. Granular consent for different data uses is likely required.

- Limited Scope for Other Legal Bases: The ruling significantly restricts the ability of advertising-funded platforms to rely on "contractual necessity" or "legitimate interests" for wide-scale data collection, combination, and personalized advertising, pushing towards an opt-in consent model.

- Increased Scrutiny: Both DPAs and NCAs (in coordination) are empowered to investigate the data processing activities of dominant platforms more intensely. Subsequent actions, like the German FCO securing commitments from Google under new national competition rules (Sec. 19a GWB) to provide users with greater choice over cross-service data combination, reflect this trend.

Conclusion

The CJEU's Meta Platforms decision represents a pivotal moment in the regulation of the digital economy in Europe. By confirming that competition authorities can factor GDPR compliance into abuse of dominance assessments and by strictly interpreting the legal bases for data processing, the Court has significantly raised the bar for dominant online platforms, particularly those reliant on personalized advertising business models. The emphasis on freely given, specific user consent is clear. This ruling is likely to drive changes in platform business practices, fuel further regulatory scrutiny, and influence the development of data protection and competition law globally.