Japan Antimonopoly Act & JFTC Enforcement (2025): A Practical Guide

TL;DR

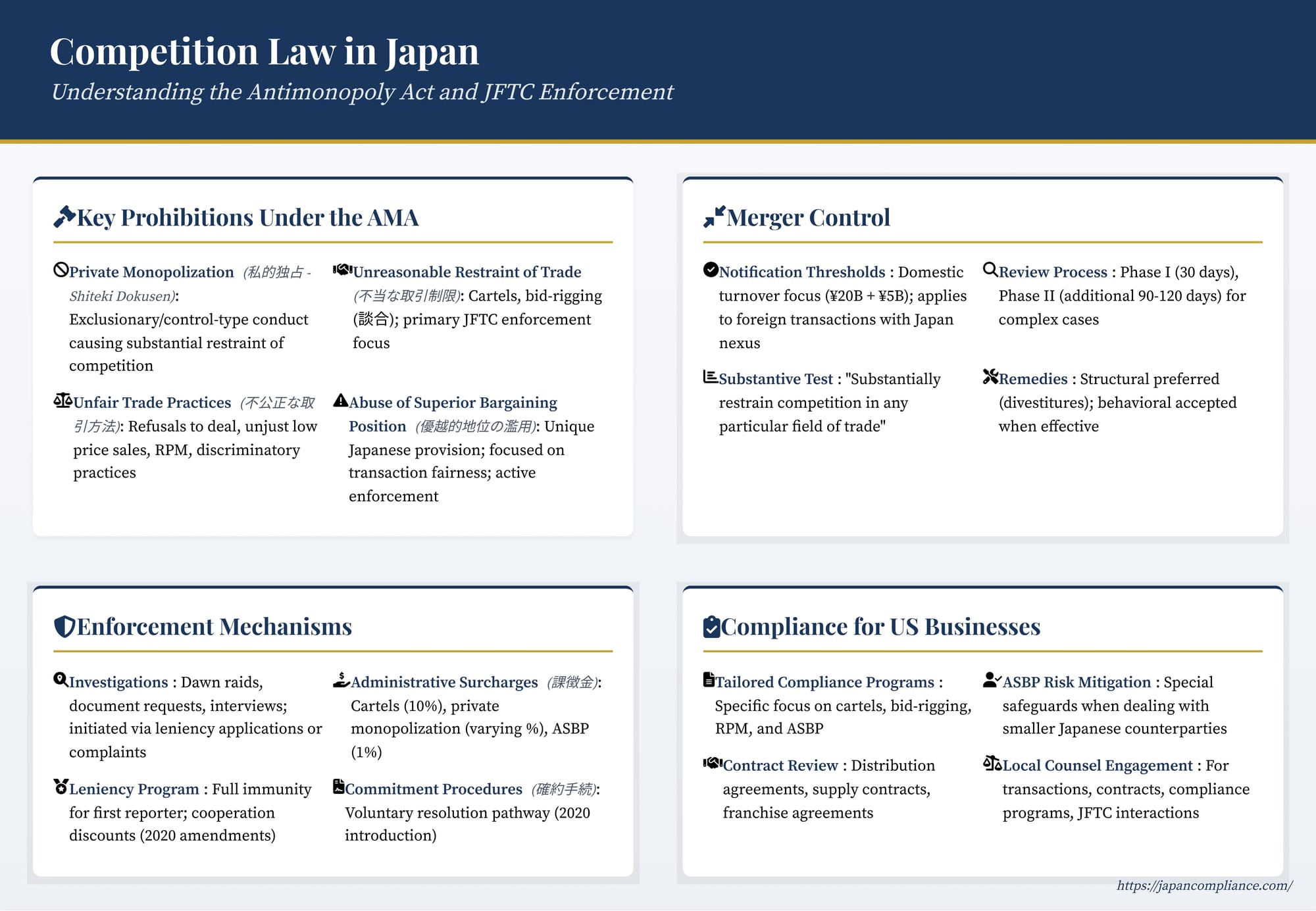

Japan’s Antimonopoly Act bars cartels, private monopolization and unfair trade practices (incl. abuse of superior bargaining position). Active JFTC enforcement + leniency + merger control mean US firms need robust compliance and deal-review processes.

Table of Contents

- Antimonopoly Act Overview

- Prohibited Conduct

- Private Monopolization

- Cartels & Bid-Rigging

- Unfair Trade Practices / ASBP

- Merger Control Rules

- JFTC Investigations & Fines

- Compliance Steps for Foreign Businesses

- Conclusion

For any US company doing business in Japan—whether through direct sales, distribution partnerships, acquisitions, or local operations—a solid understanding of Japanese competition law is indispensable. The cornerstone of this framework is the Act on Prohibition of Private Monopolization and Maintenance of Fair Trade, commonly known as the Antimonopoly Act (AMA) (私的独占の禁止及び公正取引の確保に関する法律 - Shiteki Dokusen no Kinshi oyobi Kōsei Torihiki no Kakuho ni Kansuru Hōritsu, or 独占禁止法 - Dokusen Kinshi Hō). Enforced by the vigilant Japan Fair Trade Commission (JFTC) (公正取引委員会 - Kōsei Torihiki Iinkai), the AMA governs a wide range of business activities, from mergers and market conduct to contractual relationships. This article provides an overview of the AMA's key provisions, enforcement trends, and compliance considerations relevant to foreign businesses.

I. Overview of the Antimonopoly Act (AMA)

First enacted in 1947, the AMA aims to promote fair and free competition, stimulate the creative initiative of entrepreneurs, boost employment and national income levels, and thereby assure the interests of consumers in general. It prohibits conduct that unduly restricts competition or employs unfair methods of competition. The JFTC, an independent administrative agency, is responsible for investigating potential violations, issuing orders, imposing administrative fines (surcharges), and publishing guidelines to clarify the law's application.

II. Key Prohibitions Under the AMA

The AMA broadly prohibits three main categories of anticompetitive conduct: Private Monopolization, Unreasonable Restraint of Trade, and Unfair Trade Practices.

A. Private Monopolization (私的独占 - Shiteki Dokusen)

Private monopolization (AMA Section 3, first part) refers to conduct by which a business operator, individually or through combination or conspiracy with others, excludes or controls the business activities of other operators, thereby causing a substantial restraint of competition in a particular field of trade contrary to the public interest. This covers:

- Exclusionary Conduct: Actions aimed at driving competitors out of the market or preventing new entry (e.g., predatory pricing, exclusive dealing imposed by a dominant firm, refusal to supply essential inputs).

- Control-Type Conduct: Actions aimed at controlling the business activities of other companies (e.g., acquiring stock to dictate another company's decisions, dispatching directors to control competitors).

Cases involving private monopolization are less frequent than cartel or unfair trade practice cases but can attract significant JFTC scrutiny, particularly involving dominant firms in technology or essential infrastructure sectors.

B. Unreasonable Restraint of Trade (不当な取引制限 - Futōna Torihiki Seigen)

This prohibition (AMA Section 3, second part) targets concerted actions by multiple business operators that mutually restrict or conduct their business activities in such a manner as to fix, maintain, or increase prices, or to limit production, technology, products, facilities, or customers/suppliers, thereby causing a substantial restraint of competition in a particular field of trade contrary to the public interest. The most common forms are:

- Cartels (カルテル): Agreements among competitors to fix prices, limit output, allocate markets or customers, or rig bids (談合 - dangō). This is a core focus of JFTC enforcement.

- Bid-Rigging (談合 - Dangō): Collusion among bidders in public or private tenders to predetermine the winning bidder and the winning price.

The JFTC actively investigates and penalizes cartels and bid-rigging across various industries. Recent JFTC enforcement actions (often resulting in cease and desist orders and substantial surcharges) frequently involve bid-rigging in public procurement projects initiated by national or local government bodies (e.g., recent cases reported in fiscal years 2023 and 2024 involved sectors like computer equipment procurement, geological surveys, school lunch preparation services, recycled paper, and vaccines). Price-fixing cartels have also been targeted in industries manufacturing specific goods (e.g., woodworking drills, steel pipe fittings).

Leniency Program (課徴金減免制度 - Kachōkin Genmen Seido): To detect cartels, Japan has a well-established leniency program (AMA Section 7-2). Companies that voluntarily report their involvement in a cartel or bid-rigging to the JFTC before an investigation begins can receive full immunity from administrative surcharges (課徴金 - kachōkin). Subsequent applicants can receive partial reductions. Significant amendments effective December 2020 introduced a "cooperation discount" system (調査協力減算制度 - chōsa kyōryoku gensan seido). Under this system, the percentage reduction in surcharges for leniency applicants (especially those applying after an investigation starts) depends not just on the order of application but also on the degree to which their cooperation contributes to uncovering the full facts of the violation. This incentivizes deeper and more meaningful cooperation throughout the investigation.

Violations involving unreasonable restraint of trade can also lead to criminal penalties (fines and imprisonment for individuals involved) pursued by the JFTC through criminal accusations filed with the Public Prosecutor General.

C. Unfair Trade Practices (不公正な取引方法 - Fukōsei na Torihiki Hōhō)

This category (AMA Section 19, referencing Section 2(9)) covers a broader range of conduct that tends to impede fair competition. The JFTC designates specific types of conduct as Unfair Trade Practices (UTPs) in its General Designations. Key examples relevant for international businesses include:

- Concerted Refusal to Deal / Discriminatory Treatment: Competitors agreeing to boycott a certain business, or a single firm unjustifiably refusing to supply or discriminating against certain customers.

- Unjust Low Price Sales / Price Discrimination: Selling goods or services at unduly low prices to exclude competitors, or unjustifiably charging different prices to different customers in similar situations.

- Deceptive Customer Inducement / Tie-in Sales: Misleading customers about products/services, or forcing customers to buy an unwanted product (tied product) to obtain a desired one (tying product).

- Resale Price Maintenance (RPM) (再販売価格維持 - Saihanbai Kakaku Iji): Suppliers dictating the resale prices charged by their distributors or retailers without justifiable grounds. This is generally considered illegal per se in Japan, with limited exceptions.

- Abuse of Superior Bargaining Position (優越的地位の濫用 - Yūetsuteki Chii no Ranyō): This is a particularly unique and actively enforced provision under Japanese competition law (AMA Section 2(9)(v)). It prohibits a business operator from unjustly taking advantage of its superior bargaining position relative to a counterparty by imposing disadvantageous terms or demands that deviate from normal commercial practices.

Understanding Abuse of Superior Bargaining Position (ASBP):

This concept differs from typical US antitrust analysis focused on market power and consumer harm. ASBP focuses on the fairness of the transaction itself, protecting the weaker party in a relationship where bargaining power is significantly imbalanced. Three elements must be met:

- Superior Bargaining Position: Party A is deemed to have a superior bargaining position over Party B if B heavily depends on transactions with A, making it difficult for B to refuse A's requests, even if disadvantageous, due to fear of significant business disruption (e.g., termination of取引). This is assessed based on factors like market position, B's reliance on A, possibility of switching partners, etc. It doesn't require A to have market dominance in the traditional antitrust sense.

- Leveraging the Position: The action must be taken by leveraging this superior position.

- Unjust Disadvantage Contrary to Normal Commercial Practices: The conduct must impose an unjust disadvantage on the counterparty in light of normal business practices.

The JFTC's guidelines provide examples of conduct likely to constitute ASBP:

* Coerced Purchase/Use: Forcing the counterparty to purchase goods or services unrelated to the main transaction.

* Request for Economic Benefits: Demanding monetary contributions (協賛金 - kyōsan-kin), uncompensated labor (e.g., requiring supplier employees to work at the buyer's store without payment), or other economic benefits beyond the agreed price.

* Unjust Returns/Redoing Work: Returning goods without justifiable reason (e.g., after inspection period, minor defects) or demanding rework without bearing costs.

* Unjust Price Reduction/Delayed Payment: Unilaterally reducing agreed prices after the transaction or delaying payment without reason.

* Imposing Disadvantageous Conditions: Setting unreasonable terms regarding quantity, delivery times, or requiring disclosure of confidential information without justification.

ASBP is a major compliance risk area, particularly for large buyers dealing with smaller suppliers, franchisors dealing with franchisees, and increasingly, digital platforms dealing with business users. The JFTC frequently investigates and issues orders related to ASBP, often alongside enforcement of the Subcontract Act (下請法 - Shitauke Hō), which provides specific protections for subcontractors in certain types of transactions. Potential amendments to the Subcontract Act discussed for 2025 aim to further strengthen protections, for example, regarding payment terms (prohibiting promissory notes) and ensuring proper negotiation over prices, reflecting ongoing policy focus in this area.

III. Merger Control (企業結合審査 - Kigyō Ketsugō Shinsa)

The AMA requires parties to notify the JFTC in advance of certain types of transactions (mergers, acquisitions, joint ventures, etc.) that meet specific thresholds, primarily based on the domestic turnover of the parties involved.

A. Notification Thresholds

Pre-merger notification is generally required for:

- Stock Acquisitions: If the acquiring company group's domestic turnover exceeds JPY 20 billion AND the target company (and its subsidiaries) has domestic turnover exceeding JPY 5 billion, AND the acquisition results in the acquirer holding over 20% or 50% of the target's voting rights.

- Mergers: If one merging company group's domestic turnover exceeds JPY 20 billion AND another merging company group's domestic turnover exceeds JPY 5 billion.

- Business Transfers: Thresholds apply based on the turnover of the transferring business and the acquiring company group.

- Joint Ventures: Specific rules apply depending on the structure.

These thresholds focus on domestic turnover in Japan, meaning foreign-to-foreign transactions can trigger notification if both parties have significant sales within Japan. Failure to notify reportable transactions can result in fines.

B. Review Process and Substantive Test

Once notified, the JFTC reviews the transaction to determine if it "may be substantially to restrain competition in any particular field of trade" (AMA Section 10, 15, etc.).

- Review Phases: There's an initial 30-day waiting period (Phase I). If the JFTC requires further review, it requests additional information, initiating a Phase II review, which typically concludes within 120 days after the notification filing date or 90 days after the submission of all requested additional information, whichever is later.

- Substantive Analysis: The JFTC defines relevant product and geographic markets and analyzes potential anticompetitive effects (unilateral effects, coordinated effects) resulting from horizontal, vertical, or conglomerate integration. Factors considered include market shares, market concentration (HHI), barriers to entry, competitive pressures from imports or neighboring markets, and user opinions.

- Recent Trends: The JFTC increasingly uses economic analysis (e.g., price correlation studies, merger simulations) in complex cases. There is heightened scrutiny of transactions in digital markets, focusing on data aggregation, network effects, and potential impacts on innovation. The JFTC also actively monitors non-notifiable transactions (below thresholds) that might raise competition concerns, particularly potential "killer acquisitions" where a large firm acquires a nascent competitor primarily to eliminate future competition. The JFTC has the authority to open investigations into non-notifiable deals and may encourage parties to file voluntarily if potential issues exist.

C. Remedies

If the JFTC identifies competition concerns, it will discuss potential remedies with the parties. These can be:

- Structural Remedies: E.g., divestiture of overlapping businesses or assets.

- Behavioral Remedies: E.g., commitments regarding pricing, supply obligations, access to infrastructure, or firewalls to prevent information sharing.

The JFTC prefers structural remedies where feasible but accepts behavioral remedies if they effectively address the concerns. Clearance is often conditional upon implementation of agreed remedies.

IV. Enforcement Mechanisms and Remedies

The JFTC possesses strong enforcement powers to address AMA violations.

A. JFTC Investigations and Orders

- Investigations: The JFTC can initiate investigations based on leniency applications, complaints, or its own market monitoring. Investigations can involve requests for information, on-site inspections ("dawn raids"), and interviews.

- Cease and Desist Orders (排除措置命令 - Haijo Sochi Meirei): If a violation is found, the JFTC typically issues a cease and desist order requiring the infringing party to stop the conduct and take measures to restore competition (e.g., notify customers of the violation, implement compliance programs).

- Administrative Surcharges (課徴金 - Kachōkin): For cartels, bid-rigging, private monopolization (certain types), and certain UTPs (including ASBP), the JFTC imposes administrative fines calculated based on the affected turnover during the violation period (typically up to 3 years). Base rates vary by violation type (e.g., 10% for standard cartels, 1% for ASBP), with potential adjustments for factors like duration, prior offenses, and cooperation (leniency). The 2020 amendments refined these calculations to better capture the economic benefit derived from the violation.

- Commitment Procedures (確約手続 - Kakuyaku Tetsuzuki): Introduced by the 2020 amendments, this allows the JFTC and the investigated party to voluntarily resolve suspected AMA violations. If the party proposes commitments sufficient to address the competition concerns, and the JFTC approves them, the JFTC can close the investigation without issuing findings of fact or law regarding a violation. This offers a potentially faster and less adversarial resolution pathway.

B. Leniency Program Refinements

As mentioned, the leniency program is a key tool against cartels. The 2020 amendments aimed to increase its effectiveness and fairness by introducing the cooperation discount system and providing slightly more predictability regarding surcharge reductions based on cooperative efforts beyond mere reporting order.

C. Limited Attorney-Client Privilege Analogue (判別手続 - Hanbetsu Tetsuzuki)

Also introduced in 2020, this procedure applies specifically in the context of surcharge investigations for unreasonable restraints of trade (cartels/bid-rigging). It allows businesses under investigation to request that certain documents containing communications with their external legal counsel regarding the suspected AMA violation be reviewed by designated JFTC officials (separate from the investigation team) to determine if they meet specific criteria (confidentiality, legal advice purpose). If confirmed, these specific documents are returned to the company without the main investigation team reviewing their contents. This provides limited protection akin to attorney-client privilege but is narrower than in the US and applies only under specific procedural conditions related to surcharge investigations.

D. Private Enforcement

Individuals or businesses harmed by AMA violations can file private lawsuits seeking damages in Japanese courts.

- Damages Claims (AMA Section 25): After a JFTC cease and desist order or surcharge order becomes final and unappealable, affected parties can sue the violators for damages under a special provision (AMA Section 25). Under this section, the defendant businesses cannot deny their intent or negligence regarding the violation.

- General Tort Claims: Parties can also potentially sue under the general tort provisions of the Civil Code (Article 709), which does not require a prior finalized JFTC order but requires the plaintiff to prove intent or negligence, causation, and damages.

While private antitrust litigation is less frequent and typically yields lower damages compared to the US system, it remains a potential avenue for redress, especially following JFTC action.

V. Compliance Considerations for US Businesses

Given the AMA's breadth and the JFTC's active enforcement, robust compliance efforts are essential:

- Tailored Compliance Programs: Implement a comprehensive antitrust compliance program specifically addressing Japanese AMA risks. This should cover cartels, bid-rigging, RPM, and particularly ASBP, given its unique nature and frequent enforcement.

- Training: Conduct regular training for relevant personnel (sales, marketing, procurement, management) on AMA principles and company policy. Training should be practical and cover red flags for risky conduct.

- Contract Review: Carefully review distribution agreements, supply contracts, franchise agreements, and standard terms and conditions to ensure compliance with rules on RPM, ASBP, and other UTPs.

- M&A Due Diligence: Thoroughly assess merger control filing requirements for any Japan-related transaction. Conduct substantive antitrust due diligence to identify potential competition risks early.

- Pricing Policies: Ensure pricing strategies comply with rules against price discrimination and unjust low-price sales. Ensure any resale price recommendations are clearly non-binding.

- ASBP Risk Mitigation: If your company potentially holds a superior bargaining position relative to Japanese counterparties (suppliers, distributors, franchisees), implement specific safeguards and training to prevent conduct that could be deemed abusive (e.g., clear justification for returns, fair negotiation processes, avoiding coerced purchases or contributions).

- Seek Local Counsel: Engage experienced Japanese antitrust counsel for advice on specific transactions, contractual arrangements, compliance program design, and responding to JFTC inquiries or investigations.

Conclusion

Japan's Antimonopoly Act provides a comprehensive framework for regulating competition, actively enforced by the JFTC. From strict prohibitions on cartels and bid-rigging, facilitated by a robust leniency program, to detailed merger control reviews and the unique regulation of Abuse of Superior Bargaining Position, the AMA significantly shapes the business environment. Recent amendments have further refined enforcement tools like the surcharge system and introduced mechanisms like commitment procedures and limited protections for attorney communications. For US companies engaging with the Japanese market, understanding these rules and prioritizing proactive compliance are critical steps to mitigating legal risks and fostering sustainable business operations.