Company Splits and Worker Rights: Japan's Supreme Court on Consultation Duties (July 12, 2010)

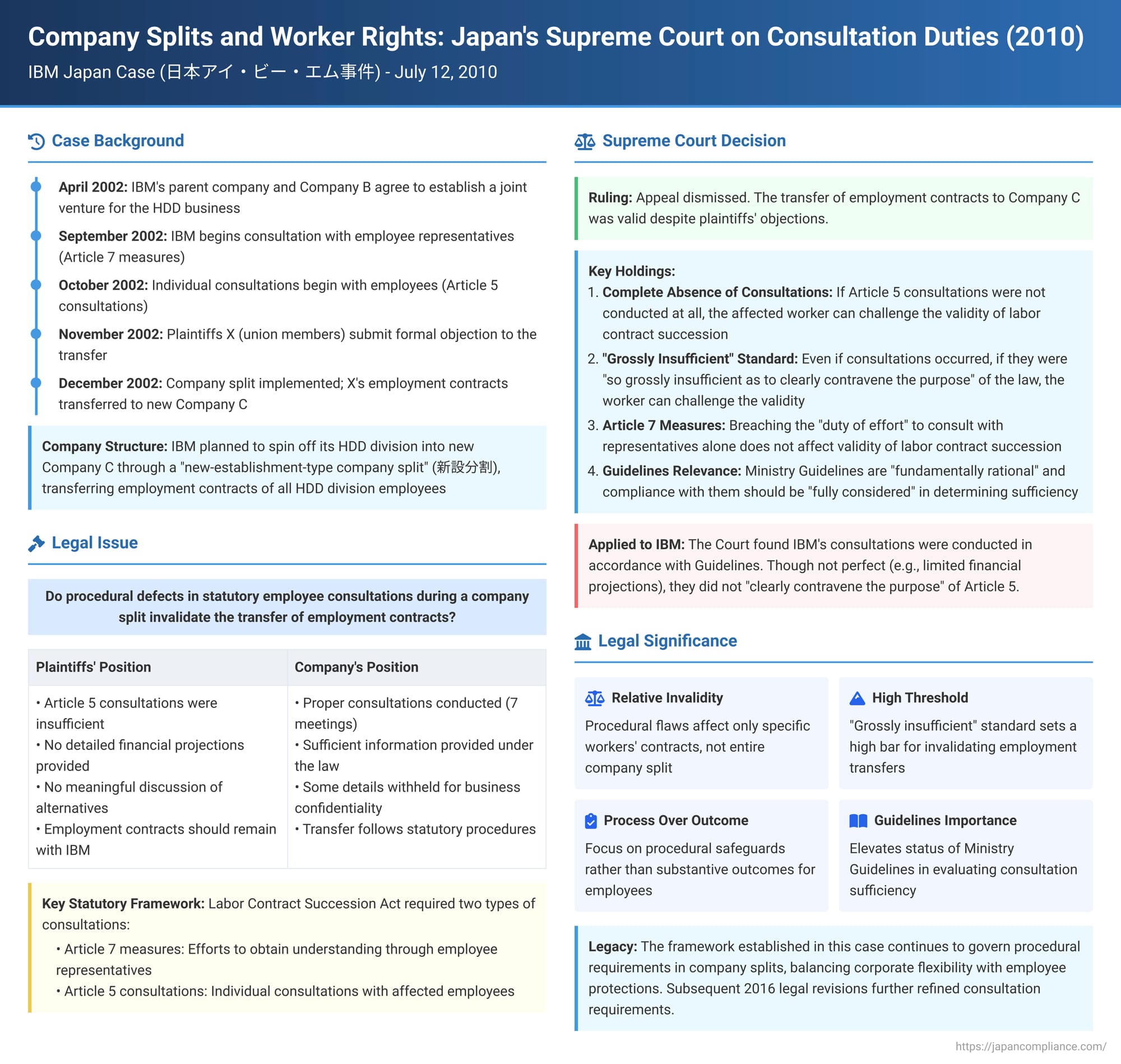

On July 12, 2010, the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a significant judgment in a case. This ruling provided crucial clarification on the legal consequences for individual employment contracts when an employer is alleged to have inadequately fulfilled its statutory obligations to consult with employees during a company split (会社分割 - kaisha bunkatsu). The decision established an important framework for how defects in these procedural safeguards affect the transfer of employment contracts to a newly formed or succeeding company.

The Corporate Restructuring and Employee Concerns

The defendant, Company Y, was a major computer manufacturing and services company, operating as a wholly-owned subsidiary of a U.S.-based parent, Corporation A. The plaintiffs, X and others (Plaintiffs X), were employees working in Company Y's Hard Disk Drive (HDD) business division and were members of the Z Labor Union branch (the Union Branch).

The dispute arose from a significant corporate restructuring involving Company Y's HDD business:

- The Joint Venture and Spin-Off Plan: Around April 2002, Corporation A (Company Y's parent) and another entity, Company B, reached an agreement to establish a joint venture focused specifically on the HDD business. To facilitate this, Company Y planned to spin off its entire HDD business division into a newly created company (Company C) through a "new-establishment-type company split" (新設分割 - shinsetsu bunkatsu). This new Company C was slated to become a subsidiary of the aforementioned joint venture. Concurrently, Company B also planned to spin off its HDD operations and transfer them to Company C.

- Transfer of Employment Contracts: A core part of this restructuring was the intended transfer of the employment contracts of all employees then working in Company Y's HDD business division to the new Company C.

Statutory Consultation Procedures and Their Implementation

Japanese law at the time (primarily the Commercial Code provisions concerning company splits and the Labor Contract Succession Act, 承継法 - Shōkeihō, before its later amendments) mandated specific procedures to protect employees affected by such corporate reorganizations. Two key obligations on the splitting company (Company Y in this case) were:

- Article 7 Measures (Efforts to Obtain Employee Understanding and Cooperation): This required the splitting company to endeavor to obtain the understanding and cooperation of its employees regarding the company split and the succession of labor contracts. This was typically achieved through explanations and consultations with employee representatives.

- Company Y implemented these measures by:

- Having employee representatives elected at each of its worksites.

- Commencing information provision via its intranet on September 3, 2002, including details of the company split, employment-related matters, and establishing a Q&A portal.

- From September 27, 2002, holding briefings for these employee representatives (70 representatives divided into four groups). These briefings covered the background and objectives of the split, an overview of Company C's planned business, identification of departments to be transferred, the terms and conditions for employees at Company C, the criteria for determining which employees were "mainly engaged" (主として従事する労働者 - shu to shite jūji suru rōdōsha) in the transferring HDD business (a key category under the Succession Act), methods for resolving labor-management issues, and answers to questions regarding Company C's financial viability and ability to meet its obligations.

- Creating an intranet database containing various relevant documents for access by employee representatives.

- Conducting specific, separate consultations with employee representatives from the D worksite, which was anticipated to be a central facility for the new Company C, and providing written responses to their formal requests.

- Company Y implemented these measures by:

- Article 5 Consultations (Consultations with Individual Employees): Supplementary provisions to the then-amended Commercial Code (specifically,附則5条1項 - fusoku go-jō ikkō) required the splitting company to consult with individual employees whose labor contracts were to be succeeded by the new company, before finalizing the split plan.

- Company Y addressed this by:

- On October 1, 2002, providing line managers within the HDD business division with materials for these individual consultations. These materials included a draft of Company C's proposed work rules and the documents previously used for the Article 7 explanations to employee representatives.

- Instructing these line managers to use these materials to explain the situation to their respective employees by October 30, to ascertain each employee's intentions regarding the transfer of their employment contract to Company C, and importantly, to conduct a minimum of three consultation sessions with any employee who expressed unwillingness to transfer.

- Most employees, following these procedures, reportedly agreed to the transfer.

- Consultations with Plaintiffs X: Plaintiffs X, choosing to be represented by their Union Branch, engaged in seven consultation sessions with Company Y management, which were further supplemented by three exchanges of written correspondence. During these interactions, Company Y provided explanations concerning Company C's business overview and the company's determination that Plaintiffs X fell into the category of employees "mainly engaged" in the transferring HDD business. However, Company Y did not provide responses in the exact format requested by the Union Branch on certain matters. For instance, regarding detailed financial projections for Company C, Y stated that specific figures were confidential business information but offered general positive outlooks based on the joint venture. Concerning future working conditions at Company C, Y indicated that these would be determined by Company C itself, subject to applicable labor protection laws. Company Y also declined the Union Branch's request to allow Plaintiffs X to remain with Company Y via an internal transfer or an "on-the-books" secondment to Company C.

- Company Y addressed this by:

- Plaintiffs X's Formal Objection and Subsequent Transfer: On November 11, 2002, Plaintiffs X, through their Union Branch, submitted a formal written objection to Company Y. They asserted that the explanations provided by the company had been insufficient and that the consultation process had been insincere. They explicitly objected to the transfer of their employment contracts to Company C.

Despite these objections, the company split was formally registered on December 25, 2002, establishing Company C (with a capital of 5 billion yen). The employment contracts of Plaintiffs X were deemed to have been transferred to Company C as part of this process.

Plaintiffs X then filed a lawsuit against Company Y, seeking legal confirmation that their employment relationship continued to exist with Company Y (i.e., that the transfer of their contracts to Company C was invalid and ineffective). They also claimed damages for alleged tortious acts by Company Y. Both the Yokohama District Court (first instance) and the Tokyo High Court (on appeal) dismissed all of Plaintiffs X's claims, upholding the validity of the employment contract transfers. Plaintiffs X then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Judgment: Procedural Thresholds for Invalidating Contract Succession

The Supreme Court dismissed the appeal by Plaintiffs X, thereby affirming the High Court's decision that the transfer of their employment contracts to Company C was valid. However, in doing so, the Supreme Court laid out an important framework for how procedural defects in the statutory consultation processes affect the validity of labor contract succession in company splits.

I. The Purpose of Article 5 Consultations

The Court began by defining the legislative intent behind the Article 5 consultation requirement: "This [Article 5 consultation requirement] is understood to have been established with the aim of protecting workers, by requiring the splitting company, prior to determining the succession of individual workers' labor contracts when preparing the split plan, to consult with individual workers engaged in the business to be succeeded, and to make its determination on succession while also taking into account the wishes, etc., of the said workers, given that the succession of labor contracts can bring about significant changes to the workers' status."

II. The Legal Effect of Defective Article 5 Consultations

This was the core of the judgment regarding the plaintiffs' primary claim:

- Presumption of Succession for "Mainly Engaged" Workers: The Court noted that under Article 3 of the (then) Labor Contract Succession Act, workers "mainly engaged" in the business being spun off are generally in a position where they cannot object to the splitting company's decision to transfer their employment contracts.

- Proper Consultation as a Prerequisite: However, the Court crucially stated: "the aforementioned purpose of Article 5 consultations implies that Article 3 of the Succession Act naturally presupposes that Article 5 consultations have been properly conducted and that the protection of the said workers has been ensured."

- Complete Absence of Consultation: "Viewed in this light, if Article 5 consultations were not conducted at all with a specific worker in the above category [mainly engaged], it is reasonable to conclude that the said worker can challenge the validity of the labor contract succession stipulated by Article 3 of the Succession Act."

- "Grossly Insufficient" Consultation: "Furthermore, even if Article 5 consultations were conducted, if the explanations or the content of the consultations by the splitting company were so grossly insufficient as to clearly contravene the purpose for which the law requires Article 5 consultations, this can be evaluated as a breach of the splitting company's Article 5 consultation duty, and it should be said that the said worker can challenge the validity of the labor contract succession stipulated by Article 3 of the Succession Act."

III. The Legal Effect of Defective Article 7 Measures

Regarding the broader Article 7 measures (efforts to obtain understanding and cooperation through employee representatives), the Court held:

- These measures impose a "duty of effort" (努力義務 - doryoku gimu) on the splitting company.

- A breach of these Article 7 obligations, in itself, does not constitute a reason that affects the validity of the labor contract succession.

- The adequacy of Article 7 measures would only become a relevant consideration "as one factor in judging whether there has been a breach of the Article 5 consultation duty, in special circumstances such as where insufficient information provision, etc., during the Article 7 measures resulted in the Article 5 consultations lacking substance."

IV. The Role of Official Guidelines

The Court also addressed the significance of the official "Guidelines concerning appropriate measures to be taken by splitting companies and succeeding companies, etc., regarding the succession of labor contracts and collective agreements concluded by the splitting company" (issued by the Ministry of Labour in 2000, and subsequently revised).

- It found the provisions of these Guidelines to be "fundamentally rational."

- It stated: "In determining whether Article 7 measures or Article 5 consultations conducted in an individual case meet the law's intended purpose, whether they were conducted in accordance with the Guidelines should also be fully considered." The Guidelines detail matters that should be explained, such as the background and reasons for the split, criteria for determining if a worker is "mainly engaged," and the new company's outline.

V. Application to Company Y's Actions

Applying this framework, the Supreme Court found:

- Company Y's Article 7 measures (explanations to employee representatives, provision of information via intranet, specific discussions with D worksite representatives) were consistent with the Guidelines and "cannot be said to have been insufficient."

- Company Y's Article 5 consultations (provision of materials to line managers, instructions for multiple discussions with unwilling employees, direct engagement with Plaintiffs X via their Union Branch including seven meetings and written exchanges, explanation of Company C's outline and X's "mainly engaged" status) were also largely in line with the Guidelines. While Company Y did not respond to all of X's demands in the exact manner requested (e.g., detailed financial figures for Company C, requests for internal transfer/secondment), the Court found reasonable grounds for these responses given business confidentiality and the strategic purpose of the split.

- Therefore, the Court concluded that Company Y's Article 5 consultations "cannot be said to clearly contravene the purpose for which the law requires Article 5 consultations."

VI. Overall Conclusion

"Based on the above, Company Y's Article 5 consultations cannot be said to have been insufficient, and it cannot be said that the succession of Plaintiffs X's labor contracts to Company C is ineffective. Furthermore, a tort based on insufficient Article 5 consultations, etc., is not established."

Significance and Implications of the Judgment

The Supreme Court's decision in the Tech Company Y (IBM Japan) case was the first by the nation's highest court to provide a detailed framework for assessing the impact of procedural deficiencies in statutory employee consultations during company splits on the validity of ensuing labor contract transfers.

- "Relative Invalidity" for Procedural Flaws: A key aspect of the ruling is its endorsement of what commentators term "relative invalidity." Prior to this judgment, official guidelines and some legislative commentary had suggested that a complete failure to conduct Article 5 consultations could potentially render the entire company split void (an "absolute invalidity" with wide-ranging corporate law consequences). The Supreme Court, however, clarified that if Article 5 consultations are either entirely omitted or are grossly insufficient with respect to a specific worker, then that worker can individually challenge the validity of the transfer of their own employment contract. This approach is seen as providing a more targeted and proportionate remedy for affected employees without necessarily jeopardizing the entire corporate reorganization, a stance now reflected in revised official Guidelines (2016).

- High Threshold for Invalidating Succession: While establishing that procedural flaws can invalidate a contract transfer, the Supreme Court set a high bar: the defect must be either a complete lack of consultation or consultations that are "so grossly insufficient as to clearly contravene the purpose" of the law. This suggests that minor or debatable shortcomings in the consultation process are unlikely to be enough to overturn the succession of a labor contract. The focus is on whether the core protective purpose of the consultation was fundamentally undermined.

- Emphasis on Procedural Protections: The Court's reasoning underscores that the Article 5 consultation process is primarily a procedural safeguard. Its aim is to ensure that employees are adequately informed and have an opportunity to express their views and wishes before a decision with significant personal consequences is finalized by the company. The Supreme Court notably did not adopt the High Court's suggestion that "significant disadvantage" to a worker could, in itself, be a substantive ground for invalidating succession due to flawed consultations.

- Limited Impact of Article 7 Deficiencies: The judgment confirmed the prevailing understanding that the Article 7 obligation on employers to seek general employee understanding and cooperation is a "duty of effort," and its breach alone does not nullify contract transfers. It only becomes a factor if it materially taints the substance of the individual Article 5 consultations.

- Guidance on Official Guidelines: The Court's affirmation of the "fundamental rationality" of the Labor Ministry's Guidelines and the need to consider them in assessing compliance lends significant weight to these administrative directives in practice.

Post-Judgment Developments:

It is important to note that Japanese company law and the related Labor Contract Succession Act and Guidelines have undergone further revisions since this 2010 judgment (e.g., the 2005 comprehensive Company Act, and 2016 revisions to the Succession Act Guidelines). These changes have, for instance, broadened the scope of employees who can be transferred (including those not "mainly engaged" in the spun-off business, who are now also entitled to Article 5 consultations if their contracts are to be transferred), and further clarified rules around disclosure of financial viability and the handling of tenseki (direct transfer of employment) agreements made in the context of company splits. These later developments build upon, and sometimes refine, the landscape in which the principles of the Tech Company Y case operate.

Conclusion: Procedural Safeguards Matter, But Perfection Not Demanded

The Supreme Court's ruling in the Tech Company Y (IBM Japan) case provided crucial clarity on the legal effect of procedural obligations during company splits. It affirmed that while employers must genuinely engage in the statutory consultation processes designed to protect employees, only severe deficiencies—amounting to a near-total failure or a consultation so flawed that it defeats the law's protective purpose—will entitle an individual worker to successfully challenge the transfer of their employment contract to a new entity. The decision underscored the importance of these procedural safeguards but also indicated that a high threshold must be met to invalidate a contract succession on such grounds alone, particularly when the employer has made demonstrable efforts to comply with the spirit of the law and official guidelines.