Company Assumes Director's Debt: A Japanese Supreme Court Landmark on Indirect Conflicts of Interest and Third-Party Rights

Case: Action for Payment of Accounts Receivable

Supreme Court of Japan, Grand Bench, Judgment of December 25, 1968

Case Number: (O) No. 1327 of 1967

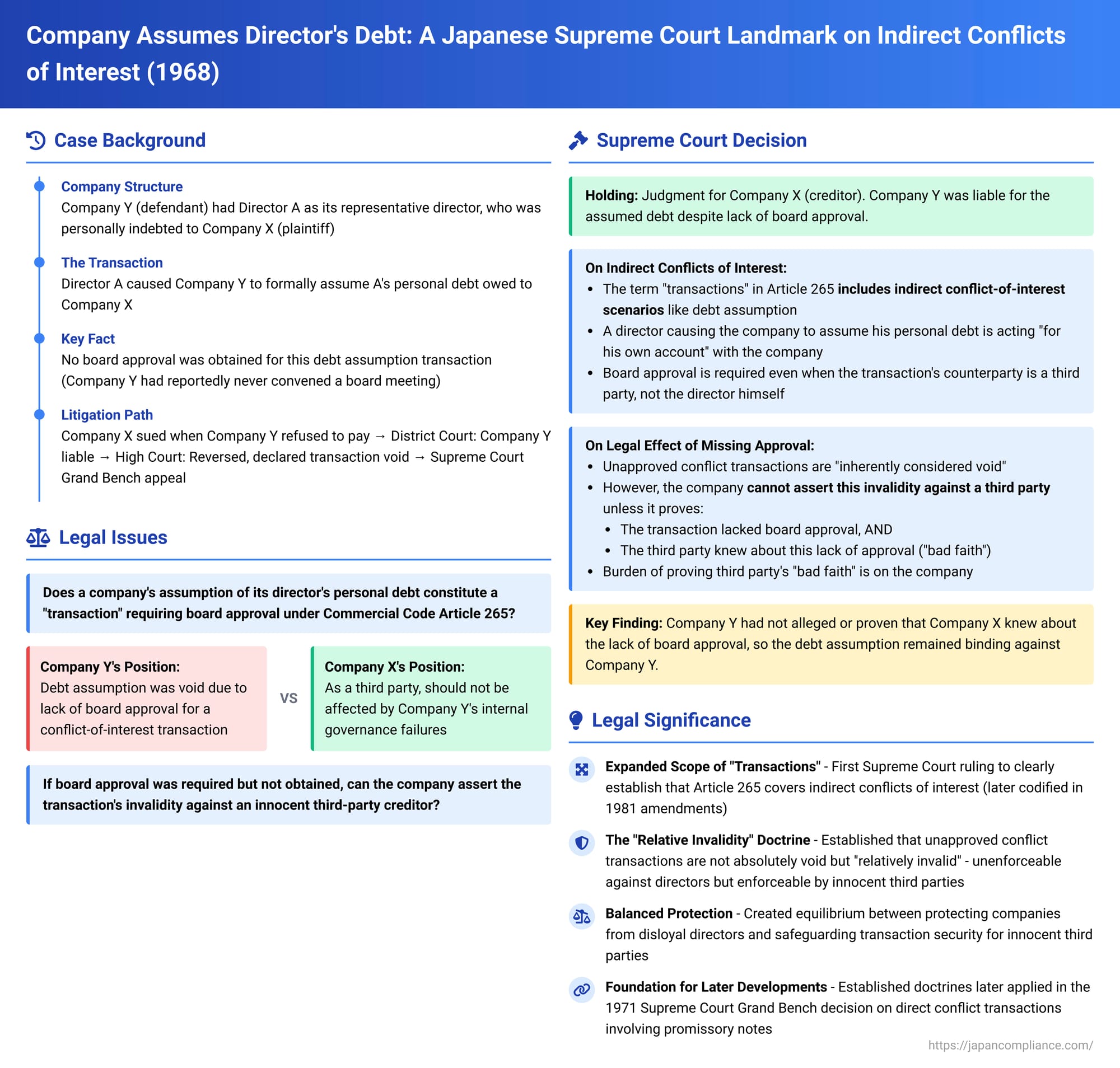

Directors of a company stand in a fiduciary relationship to it, obliged to act in the company's best interests. When a director's personal interests potentially clash with the company's, such as in transactions between the director and the company, specific safeguards are necessary. Japanese company law has long mandated that such "conflict-of-interest transactions" receive prior approval from the company's board of directors. While this rule clearly applies to direct dealings (e.g., the company selling property to a director), its application to indirect scenarios – where the company transacts with a third party, but the deal primarily benefits a director – was less clear. A landmark Grand Bench decision by the Japanese Supreme Court on December 25, 1968, provided crucial clarification, holding that such indirect transactions also fall under the approval requirement and establishing how the lack of such approval affects the rights of innocent third parties.

A Director's Debt, The Company's Burden: Facts of the Case

The dispute involved Company X (the plaintiff/appellant creditor) and Company Y (the defendant/respondent debtor company). A was the representative director of Company Y and also personally indebted to Company X.

The core of the issue was a "debt assumption" agreement. A, acting in his capacity as the representative director of Company Y, caused Company Y to formally assume the personal debt that he (A) owed to Company X. This meant Company Y agreed to take over A's obligation to pay Company X.

Crucially, this act of Company Y assuming its representative director's personal debt did not receive the approval of Company Y's board of directors. In fact, the evidence suggested that Company Y had not convened a board meeting since its incorporation.

When Company Y failed to pay the assumed debt, Company X initiated a lawsuit to recover the amount.

The Lower Courts' Diverging Paths

The court of first instance (Nagoya District Court) ruled in favor of Company X, holding Company Y liable for the debt.

However, the appellate court (Nagoya High Court) reversed this decision. The High Court found that Company Y's assumption of RD A's personal debt was indeed a conflict-of-interest transaction that required the approval of Company Y's board under the then-Commercial Code Article 265. Since this approval was absent, the High Court concluded that the debt assumption agreement was void and Company Y was not liable. Company X then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Grand Bench Decision: Protecting Good-Faith Creditors

The Supreme Court's Grand Bench, its highest adjudicatory body, overturned the High Court's decision (except for a minor portion of the claim which the High Court had allowed and was not contested further) and largely ruled in favor of the plaintiff, Company X, holding Company Y liable for the assumed debt.

Reasoning of the Apex Court: Balancing Company Protection and Transaction Safety

The Grand Bench's reasoning was delivered in two main parts:

I. The Scope of "Transactions" Requiring Board Approval Includes Indirect Conflict-of-Interest Transactions:

The Court first addressed whether an act like Company Y assuming RD A's personal debt to Company X falls under the purview of Article 265 of the then-Commercial Code. This article (analogous to parts of Article 356 and Article 365 of the current Companies Act) required board approval for a director to engage in "transactions for his own account or for that of a third party with the company."

- The Supreme Court stated that the fundamental legislative purpose of Article 265 is to prevent directors from abusing their position to pursue personal interests in a way that could harm the company and, by extension, its shareholders.

- Based on this purpose, the Court held that the term "transactions" in Article 265 should not be narrowly construed to cover only direct transactions formally made between the director and the company. It must also include acts such as a director causing the company he represents to assume his own personal debt owed to a third party. Such an act clearly benefits the director personally while potentially disadvantaging the company. Therefore, it qualifies as a transaction undertaken by the director "for his own account" with the company, even if the direct contractual counterparty of the company in the debt assumption is the third-party creditor.

- In making this pronouncement, the Supreme Court indicated it was clarifying or modifying the scope suggested by a prior, narrower interpretation from one of its Petty Benches in 1964 regarding a different type of company structure (a gōshi-gaisha, or limited partnership company).

II. The Legal Effect of Lacking Board Approval in Indirect Transactions with Third Parties – The "Relative Invalidity" Doctrine:

Having established that such an indirect debt assumption requires board approval, the Court then turned to the consequences of failing to obtain it.

- Inherent Invalidity: The Court reasoned that when a director engages in such a regulated transaction without the requisite board approval, the act should "inherently be considered void" (honrai... mukō to kaisubeki de aru). It drew an analogy to Article 108 of the Civil Code, which (at the time) prohibited an agent from acting as the other party in a transaction with their principal (self-contracting) or representing both parties to a transaction (dual agency), unless the principal consented. Article 265 of the Commercial Code stated that Civil Code Article 108 did not apply if board approval was obtained for a director's conflict-of-interest transaction. By reverse inference (a contrario), the Supreme Court suggested that if board approval was not obtained, the situation was akin to a violation of Civil Code Article 108, rendering the director's act a form of unauthorized agency and thus void.

- Direct Transactions (Company vs. Director): In a direct transaction between the company and the conflicted director, the company can naturally assert this invalidity against the director if board approval was missing.

- Indirect Transactions Involving Third Parties (Company vs. Third Party): This was the crucial part for the present case. The Court held that when a director, representing the company, enters into a transaction with an outside third party for the director's own benefit (such as Company Y assuming RD A's debt to Company X):

- Considerations of transaction safety and the need to protect bona fide third parties become paramount.

- Therefore, the company cannot assert the invalidity of the transaction against that third-party counterparty unless the company can allege and prove two things:

- That the transaction lacked the necessary board approval; AND

- That the third party (in this case, the creditor Company X) acted in "bad faith" (akui). "Bad faith" here means that the third party knew that the requisite board approval for the transaction had not been obtained.

- Application to the Facts: In this specific case, Company Y (the defendant) had not alleged, nor had it proven, that Company X (the plaintiff creditor) was in bad faith regarding the lack of board approval for Company Y's assumption of RD A's debt. Consequently, Company Y could not assert the invalidity of the debt assumption against Company X.

The Grand Bench judgment included supplementary opinions from Justice Tanaka and Justice Osumi, and a joint opinion from six other justices (Justices Yokota, Kusaka, Matsuda, Shimomura, Irokawa, and Matsumoto), all concurring in the outcome but offering different nuances in their legal reasoning, particularly concerning the interpretation of "transaction" and the theoretical basis for protecting third parties.

Analysis and Implications: Reshaping Conflict-of-Interest Jurisprudence

This 1968 Grand Bench decision had a profound and lasting impact on Japanese corporate law, particularly in how courts approach conflict-of-interest transactions involving directors.

- Broadening the Scope to "Indirect" Conflicts:

A major contribution of this judgment was its explicit recognition that the board approval requirement for director's conflict-of-interest transactions extends beyond direct dealings to encompass "indirect" transactions. This was a significant interpretive step, as the literal wording of the old Commercial Code Article 265 primarily listed examples of direct transactions. The Court’s emphasis on the legislative intent – preventing directors from self-enrichment at the company's expense – justified this broader application.

This principle was later formally codified in amendments to the Commercial Code (in 1981) and is now clearly reflected in the Companies Act (Article 356, Paragraph 1, Item 3), which explicitly covers transactions between the company and a third party where the interests of the company and a director conflict. The Court’s reasoning also implies that it doesn't necessarily matter if the director who formally represents the company in the indirect transaction is the same director who personally benefits, or another director acting in concert; the key is the existence of a conflict that could harm the company. Similarly, transactions between two companies where a director holds positions in both can fall under this rule if it creates a conflict of interest for that director in relation to one of the companies. - The "Relative Invalidity" Doctrine:

Perhaps the most crucial development was the establishment of the "relative invalidity" doctrine for such unapproved indirect transactions when a third party is involved. This means the transaction is not absolutely void against the entire world. Instead:- It is voidable or unenforceable by the company against the conflicted director.

- It is generally enforceable by a good-faith third-party counterparty against the company.

The Supreme Court analogized the lack of board approval to a situation of unauthorized agency (akin to a breach of Civil Code Article 108 on self-dealing by agents). While unauthorized agency acts are typically void unless ratified by the principal, the Court introduced a strong element of third-party protection here for reasons of transaction safety. This was a significant shift from any prior notions that might have treated such unapproved corporate acts as entirely null.

- The "Bad Faith" Standard for Third Parties:

The judgment clearly placed the burden on the company to prove that the third-party counterparty was in "bad faith" (i.e., knew about the lack of board approval) if the company wished to avoid the transaction. While the majority opinion in this 1968 case did not explicitly define whether "bad faith" would include "gross negligence" on the part of the third party, it is now widely accepted in Japanese legal theory and subsequent jurisprudence (including the Supreme Court's 1971 Grand Bench decision on direct conflict-of-interest transactions involving promissory notes, Case 55) that a third party who is grossly negligent in not knowing about the lack of approval may not be protected. The underlying principle is that only justifiable reliance by the third party warrants protection. - Harmonizing Company Protection and Transaction Safety:

This decision represents a careful balancing act. It protects the company by allowing it to disavow unapproved self-dealing transactions vis-à-vis the culpable director. However, it strongly protects external parties who deal with the company in good faith, ensuring that they are not unduly harmed by the company's internal governance failings of which they were unaware. This promotes certainty and reliability in commercial dealings. - Remedies Against the Director:

It's important to remember that even if the company is held liable to the third party for an unapproved conflict-of-interest transaction (as Company Y was to Company X in this case), the company generally retains the right to seek damages from the director(s) who caused it to enter into such a transaction without proper authorization. This director liability would typically fall under what is now Article 423 of the Companies Act (breach of duties to the company), and potentially Article 428 (stricter liability rules for directors in conflict-of-interest transactions).

Conclusion

The Supreme Court Grand Bench's decision of December 25, 1968, was a pivotal judgment that significantly modernized the Japanese legal approach to directors' conflict-of-interest transactions. By unequivocally extending the board approval requirement to "indirect" conflicts and, more importantly, by establishing the principle of "relative invalidity" for unapproved transactions involving innocent third parties, the Court struck a crucial balance. It ensured that while companies are protected from unauthorized self-dealing by their directors, the broader interests of commercial transaction safety are also upheld by safeguarding third parties who act in good faith. This ruling laid essential groundwork for later legislative reforms and continues to be a foundational precedent in Japanese corporate governance.