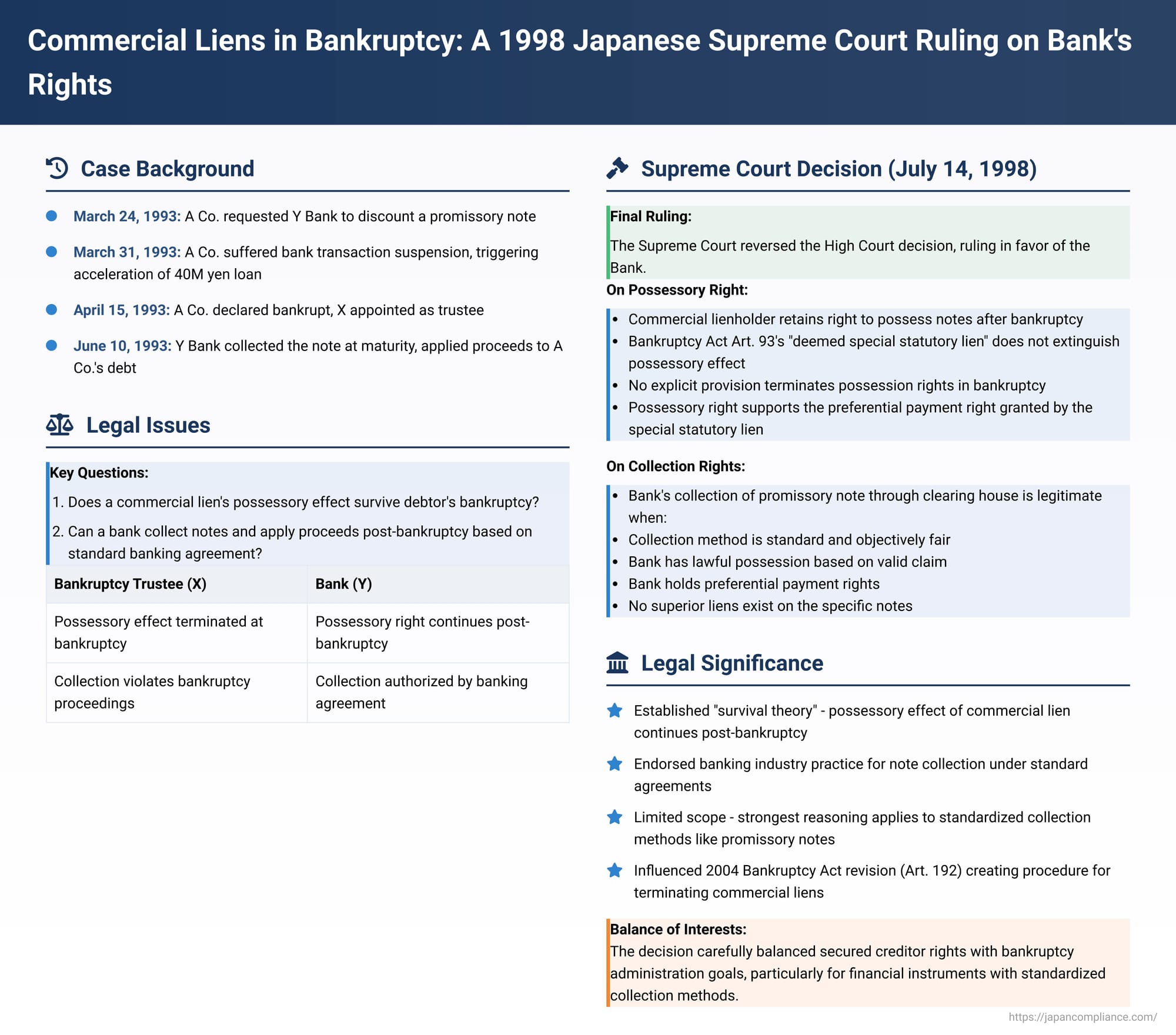

Commercial Liens in Bankruptcy: A 1998 Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Bank's Right to Possess and Collect Promissory Notes

When a company that has granted a commercial possessory lien (商事留置権 - shōji ryūchiken) to a creditor, typically a bank, over assets like promissory notes later enters bankruptcy, critical questions arise about the status and enforceability of that lien. Does the bank lose its right to physically hold the notes once bankruptcy proceedings commence? And can the bank, based on standard clauses in its banking agreement, proceed to collect these notes at maturity and apply the funds to its claims against the bankrupt company, or must it go through more formal bankruptcy or execution procedures? A Japanese Supreme Court decision from July 14, 1998, provided significant clarifications on these issues, particularly bolstering a bank's position under specific circumstances.

Factual Background: Note Held for Discount, Bankruptcy, and Bank's Actions

The case involved A Co., which on March 24, 1993, approached Y Bank with a request to discount a promissory note (referred to as "the subject note") that A Co. held. Y Bank took possession of the subject note with the intention of conducting a credit assessment of the parties to the note before deciding whether to proceed with the discount.

However, A Co.'s financial situation deteriorated rapidly. On March 31, 1993, A Co. suffered a suspension of its bank transactions (銀行取引停止処分 - ginkō torihiki teishi shobun), a severe indicator of insolvency. This event also triggered a clause in its loan agreement with Y Bank causing A Co. to lose the "benefit of time" (期限の利益を喪失 - kigen no rieki o sōshitsu) on its outstanding 40 million yen loan debt to Y Bank, making the loan immediately due.

Shortly thereafter, on April 15, 1993, A Co. was formally declared bankrupt under Japan's (then) old Bankruptcy Act, and X was appointed as its bankruptcy trustee. At this point, Y Bank had still not discounted the subject note but retained its possession. Trustee X demanded that Y Bank return the subject note to the bankruptcy estate. Y Bank refused, asserting that it held a commercial possessory lien over the note as security for its outstanding loan claim against A Co.

Subsequently, on June 10, 1993, which was the maturity date of the subject note, Y Bank proceeded to collect the full amount of the note through the established bill clearing house system. Y Bank then applied these collected proceeds towards satisfying A Co.'s loan debt.

A Co. had previously entered into a standard banking transaction agreement (銀行取引約定書 - ginkō torihiki yakujōsho) with Y Bank. Clause 4, paragraph 4, of this agreement contained typical language stating, in effect: "In the event of my failure to perform obligations to your bank, any movables, promissory notes, or other securities of mine that are in your bank's possession may be collected or disposed of by your bank..." The clause further stipulated that, in such a case, the bank could apply the net proceeds (after deducting expenses) to the customer's debts in any order deemed appropriate by the bank, without necessarily following statutory priorities.

Trustee X filed a lawsuit against Y Bank, alleging that Y Bank's refusal to return the note, followed by its collection and application of the proceeds, constituted a tortious act against the bankruptcy estate. X sought damages equivalent to the amount of the subject note (approximately 980,000 yen).

The Osaka District Court (first instance) dismissed the trustee's claim, siding with Y Bank. However, the Osaka High Court (second instance) reversed this decision, ruling in favor of trustee X. The High Court acknowledged that Y Bank had acquired a commercial possessory lien over the note. However, it held that upon A Co.'s bankruptcy declaration, this lien's possessory effect (its right to retain physical possession) was extinguished, even though the lien itself transformed into a "special statutory lien" (特別の先取特権 - tokubetsu no sakidori tokken) granting priority in payment. The High Court also found that the general clause in the banking agreement did not provide Y Bank with an arbitrary right of disposal that could override bankruptcy procedures. Y Bank appealed this adverse ruling to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Issues at Stake

The Supreme Court had to address two primary legal questions:

- Survival of the Possessory Effect of a Commercial Lien Post-Bankruptcy: When a commercial possessory lien is "deemed a special statutory lien" upon the debtor's bankruptcy (as per Article 93, paragraph 1, of the old Bankruptcy Act, now Article 66, paragraph 1, of the current Act), does the lienholder (the bank) lose its original right to physically possess the collateral (the promissory notes)?

- Bank's Right of Self-Help Collection Under a Banking Agreement: Can a standard clause in a banking agreement, which purports to allow the bank to collect or dispose of collateral in its possession upon the customer's default, authorize the bank to collect such notes and apply the proceeds to its claim after the customer has been declared bankrupt, thereby bypassing more formal bankruptcy distribution or civil execution procedures?

The Supreme Court's Ruling – Part I: Possessory Right of Commercial Lien Survives Bankruptcy Commencement

The Supreme Court reversed the High Court's decision and reinstated the first instance judgment, ultimately ruling in favor of Y Bank and dismissing the trustee's claim.

On the first issue, the Court held that: A holder of a commercial possessory lien over promissory notes belonging to what becomes the bankruptcy estate retains the right to possess (留置する権能 - ryūchi suru kennō) those notes even after the debtor's bankruptcy declaration and can legitimately refuse the bankruptcy trustee's demand for their return.

The Supreme Court's reasoning was as follows:

- Interpretation of the Statute: Article 93, paragraph 1, of the old Bankruptcy Act stated that a commercial possessory lien existing on property belonging to the bankruptcy estate "shall be deemed a special statutory lien" against the estate. The Court found that this wording—"deemed a special statutory lien"—does not inherently or automatically mean that the possessory power originally held by the commercial lienholder is extinguished.

- Lack of Explicit Extinguishing Provision: The Court noted that there was no other explicit statutory provision in the old Bankruptcy Act that mandated the extinguishment of this possessory power upon the commencement of bankruptcy proceedings.

- Purpose of Granting Special Statutory Lien Status: The legislative purpose of Article 93, paragraph 1, in deeming a commercial lien a "special statutory lien" was to grant the lienholder a right of preferential payment from the proceeds of that collateral. The Court reasoned that it would be inconsistent with this purpose if the law simultaneously stripped the lienholder of their right of possession, thereby potentially making it more difficult for them to effectively realize their priority through the execution of this special statutory lien. This was particularly true in relation to the bankruptcy trustee, whatever the lienholder's rights might be against other superior special statutory lienholders (a scenario the Court considered less likely for promissory notes and set aside with a caveat: "other special statutory lienholders against whom [the possessory right] might rank lower aside").

Therefore, Y Bank was entitled to retain possession of the subject note despite A Co.'s bankruptcy.

The Supreme Court's Ruling – Part II: Bank's Collection Under Agreement Justified for Promissory Notes

On the second issue, concerning Y Bank's right to collect the note and apply its proceeds, the Supreme Court held that Y Bank's actions were permissible under the specific circumstances and did not constitute a tort.

The Court's reasoning was more nuanced here:

- Limitations of General Banking Agreement Clauses in Bankruptcy: The Court first acknowledged that a broad, abstract clause in a banking agreement (like Clause 4(4) in this case) allowing a bank to dispose of collateral might not, as a general rule, grant an unfettered right of self-help disposal for all types of collateral in all bankruptcy situations. This is especially true considering that the special statutory lien arising from a commercial lien is, by statute (old Bankruptcy Act Article 93, paragraph 1, latter part), subordinate to certain other types of special statutory liens. Thus, a bank cannot uniformly rely on such a clause to immediately dispose of collateral outside statutory methods if, for example, superior statutory liens exist on that same collateral.

- Specific Case of Unmatured Promissory Notes: However, the Court then focused on the specific nature of the collateral in this case: unmatured promissory notes. It pointed out that the ordinary and legally prescribed method for realizing (cashing) such notes under Japan's Civil Execution Act is for a court execution officer to collect them at their maturity date by presenting them through the established bank clearing house system.

- Equivalence of Collection Methods: The Court noted that when a bank itself collects such a note through the same bill clearing house system (as Y Bank did), it is essentially using an identical, well-established, and objectively fair method of collection. This method leaves no room for the collecting party's discretion to influence the amount realized or the propriety of the process.

- Reasonableness of an Agreement Permitting Such Collection: Given this, the Supreme Court found that if a bank: (a) has lawful possession of such unmatured promissory notes based on a valid claim, and (b) holds a right to preferential payment from these notes based on its special statutory lien (which derived from its pre-existing commercial possessory lien), then an agreement (like Clause 4(4) of the banking agreement) that permits the bank to self-collect these notes at maturity via the standard clearing system and apply the proceeds to its secured claim is reasonable. The Court stated that interpreting the clause to this effect would not necessarily contradict the probable intentions of the contracting parties and, importantly, would not cause any particular harm or disadvantage provided no other special statutory liens with priority over the bank's existed on those specific notes.

- Application to the Factual Circumstances: In the present case, Y Bank had lawfully obtained possession of the subject note. Upon A Co.'s bankruptcy, its commercial lien transformed into a special statutory lien granting it priority. Y Bank's loan claim against A Co. was already due and significantly exceeded the value of the note. The note was collected through the standard clearing house procedure. Critically, there was no evidence presented of any other special statutory lienholders who had a claim on this specific note that would rank superior to Y Bank's.

Under these specific factual circumstances, the Supreme Court concluded that Y Bank was entitled, based on the agreement in Clause 4, paragraph 4, to collect the subject note via the clearing house system and apply the proceeds to its outstanding loan claim against A Co. Therefore, Y Bank's actions did not constitute a tort against the bankruptcy estate.

Significance and Implications of the Judgment

This 1998 Supreme Court decision was a landmark ruling with several key implications:

- Affirmation of the "Survival Theory" for Possessory Effect: The judgment provided strong Supreme Court authority for the view that the possessory effect of a commercial lien (the right to retain the goods) survives the commencement of the debtor's bankruptcy proceedings, at least in the bank's relationship with the bankruptcy trustee. This resolved a significant point of debate among lower courts and legal scholars.

- Endorsement of Banking Practice for Note Collection: The decision offered significant support for the practical ability of banks to realize on promissory note collateral held under commercial liens, provided they use objectively fair methods like the clearing house system and their actions are consistent with pre-existing banking agreements. This recognized the efficiency and reasonableness of such common practices.

- Scope and Limitations: The PDF commentary accompanying the case suggests that the core reasoning for permitting self-collection is strongest when applied to promissory notes due to their standardized and non-discretionary method of collection via the clearing system. The direct applicability of this part of the ruling to other types of collateral subject to commercial liens, where realization might involve more subjective valuation or diverse disposal methods, could be more limited.

- Emphasis on Lawful Possession and Priority: The bank's right to act as it did was predicated on its lawful possession of the notes and its underlying priority right derived from the commercial lien.

- Legislative Developments After the Judgment: The commentary also notes that the current Japanese Bankruptcy Act, which was comprehensively revised in 2004 (after this 1998 judgment), introduced a specific system allowing a trustee to request the termination of commercial possessory liens under certain conditions (Article 192). Some legal scholars see this legislative development as implicitly acknowledging the continued existence of the possessory right post-bankruptcy, as a specific statutory procedure for its termination would otherwise be less relevant.

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court's 1998 judgment in this case provided crucial clarifications regarding the rights of banks holding commercial possessory liens over promissory notes when a customer enters bankruptcy. The Court affirmed that the bank generally retains the right to possess the notes as against the bankruptcy trustee. Furthermore, and significantly for banking operations, it held that under a typical banking transaction agreement, the bank can proceed to self-collect such maturing notes through the established clearing house system and apply the proceeds to its secured claim, provided there are no superior specific liens on those notes and the collection method itself is objectively sound and non-discretionary. This decision carefully balanced the secured creditor rights of banks with the broader objectives of bankruptcy administration, particularly for financial instruments like promissory notes that have well-established and standardized pathways for collection.