Collective Rights, Collective Voice: Japanese Supreme Court on Iriai Associations' Standing to Sue

Date of Judgment: May 31, 1994

Case Name: Claim for Confirmation of Ownership, etc.

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

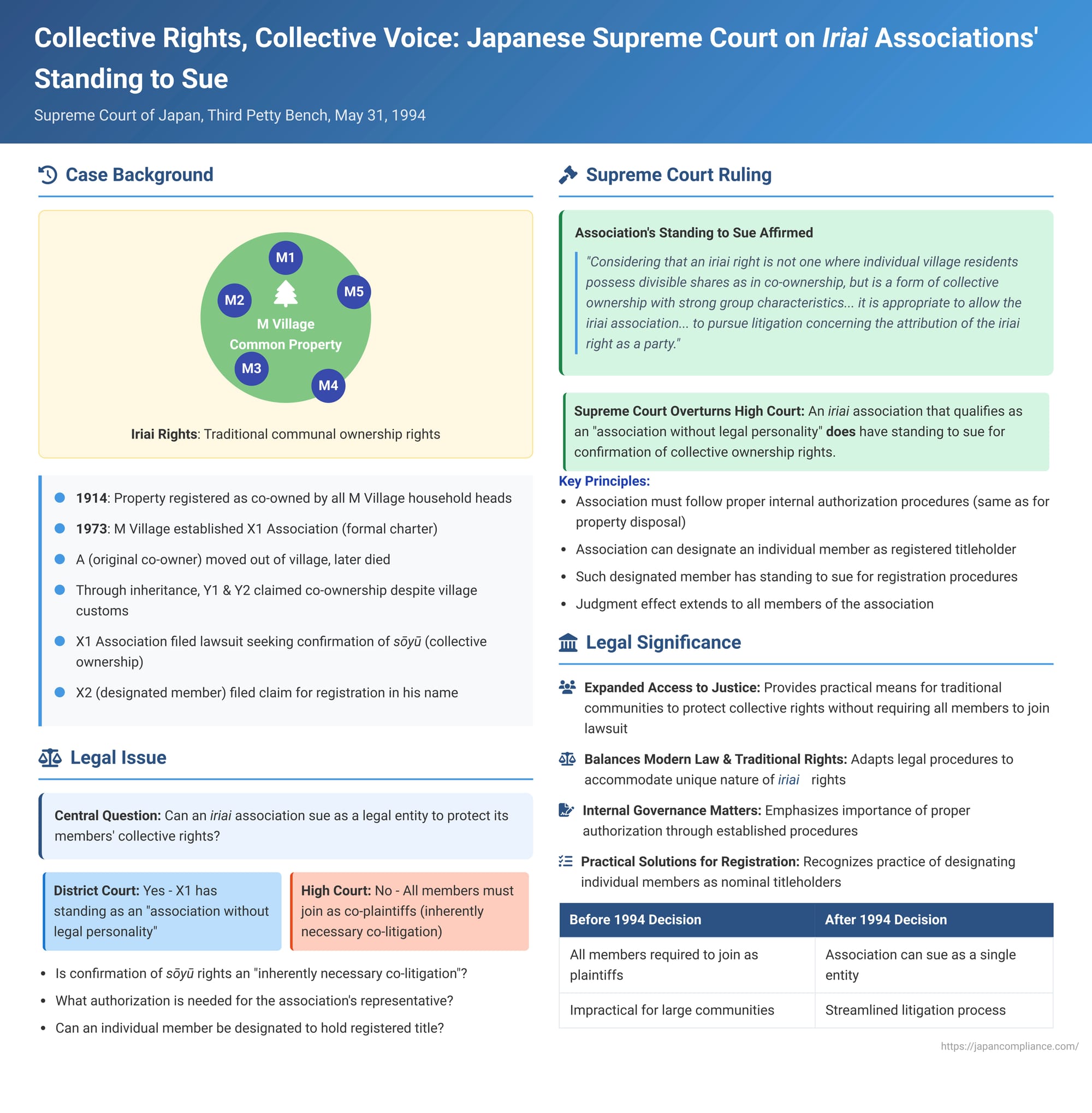

Japanese law recognizes unique forms of traditional communal landholding, notably iriai-ken (customary common rights of use, often over forests, grasslands, or fishing grounds) and property held in sōyū (a form of collective ownership by all members of a community, where individuals do not have divisible shares like in ordinary co-ownership). Protecting these ancient collective rights within a modern legal framework presents distinct challenges. A landmark Japanese Supreme Court decision on May 31, 1994, significantly clarified how communities holding such rights can vindicate them in court, particularly by affirming the standing of an iriai association to sue on behalf of its members.

The Case of M Village: A Centuries-Old Community Faces a Modern Challenge

The dispute originated from M Village, a community that had maintained its customs and managed common resources since Japan's Edo period (1603-1868).

- Traditional Iriai Lands: The residents of M Village had for generations managed various real properties, including forests and fields (the "Common Property"), as iriai-chi (common land). The specific land at the heart of this lawsuit (the "Property") was part of this Common Property.

- Early Registration: In 1914 (Taishō 3), the Property was formally registered under the names of all then-heads of households in M Village as their co-ownership (kyōyū). One of these registered co-owners was an individual named A.

- Village Customs: Long-standing village customs, reaffirmed by all household heads in 1914, governed rights to the Common Property:

- To acquire a share in the common ownership, one needed to reside within M Village for a specified period and actively participate in village duties and responsibilities.

- These common ownership rights were deeply personal to the community members; they could not be transferred to anyone other than a direct heir.

- Crucially, if a member moved out of M Village, they would automatically forfeit their rights to the Common Property.

- Formation of X1 Association: By 1973, an increase in new residents moving into the area prompted concerns about potential confusion in managing the Common Property. To address this, all members of M Village unanimously agreed to establish the M Village Property Management Association (referred to as "X1 Association" or "X1"), formalizing their traditional governance structure with a written charter.

- X1's charter stipulated that the Common Property, including the Property in dispute, would be considered the property of X1 Association.

- Membership in X1 was primarily for the traditional residents of M Village, but also extended to some new residents under defined conditions.

- Key decisions regarding the management and disposal of the Common Property, as well as the election of officers, were to be made by a general meeting of all members. The powers of X1's representative were also outlined.

- A 1977 amendment to the charter further clarified that members who moved out of the village would lose their membership qualification. It also directed that all income from the Common Property would accrue to X1's revenue, and expenditures were restricted to property management, the welfare of village members, and projects for the common benefit of the village.

- The Dispute Arises: A, one of the individuals originally registered as a co-owner in 1914, had subsequently moved out of M Village and later passed away. Despite the village custom dictating loss of rights upon departure, A's registered "share" was successively passed down through inheritance: first to B and C, and then to D. After D also died, D's heirs, Y1 and Y2 (the defendants/appellees), asserted a claim to a co-ownership share in the Property. They disputed X1 Association's position that the Property was under the sōyū (collective ownership) of all current members of X1.

- The Lawsuits: Faced with this challenge, X1 Association initiated legal proceedings against Y1 and Y2, seeking a court confirmation that the Property rightfully belonged to all members of X1 in sōyū. Simultaneously, X2, an individual member of X1 Association (and also an appellant), filed a separate claim against Y1 and Y2. X2 sought a court order compelling the registration of D's (and thus originally A's) share in X2's name, based on the principle of "restoration of a genuine registration title" (shinsei na tōki meigi no kaifuku).

Before filing these suits, X1 Association held a general meeting where all members unanimously resolved to proceed with the sōyū confirmation lawsuit and also approved designating X2 as the registered titleholder for the Property.

The Lower Courts' Diverging Paths

The case took contrasting turns in the lower courts:

- The District Court (Nagoya District Court): The trial court found in favor of the M Village community. It recognized X1 Association as an "association without legal personality" (kenri nōryoku naki shadan). This status is significant because Japanese law allows such associations to sue and be sued even if they don't have full corporate status. The District Court affirmed X1's standing to sue (genkoku tekikaku), particularly because the decision to file the lawsuit had received the unanimous approval of all its members. The court rejected Y1 and Y2's argument that the iriai right or sōyū had been dissolved or lost. It further held that any transfers of A's share occurring after A had moved out of the village were invalid, consistent with village customs. Consequently, both X1's claim for confirmation of sōyū and X2's claim for registration transfer were granted.

- The High Court (Nagoya High Court): Y1 and Y2 appealed. The High Court reversed the District Court's decision and dismissed both lawsuits. Its reasoning was that a lawsuit seeking confirmation of an iriai right, which belongs in sōyū to village residents, when brought against external parties challenging that right, constitutes an "inherently necessary co-litigation" (koyū hitsuyōteki kyōdō soshō). This procedural doctrine means that all individuals who collectively hold the right must jointly bring the lawsuit as plaintiffs. Since X1 Association sued as an entity (albeit an unincorporated one), rather than all its individual members joining as co-plaintiffs, the High Court concluded that X1 lacked the necessary standing to sue. X1 and X2 then appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision (May 31, 1994)

The Supreme Court overturned the High Court's decision and remanded the case for further proceedings, providing crucial clarifications on several legal points.

I. Standing of an Iriai Association (X1) to Sue for Sōyū Confirmation:

The Supreme Court held that an iriai association, if it qualifies as an "association without legal personality," does have the standing to sue for confirmation that property belongs in sōyū to all its members. The Court's rationale was:

"Plaintiff standing in litigation is a matter to be determined from the perspective of who should pursue the litigation as a party and against whom a judgment on the merits should be rendered for the necessary and meaningful resolution of the dispute. Considering that an iriai right is not one where individual village residents possess divisible shares as in co-ownership (kyōyū), but is a form of collective ownership with strong group characteristics subject to rules such as customs developed in the village, it is appropriate to allow the iriai association, when the village residents holding the iriai right have formed an association without legal personality, to pursue litigation concerning the attribution of the iriai right as a party and receive a judgment on the merits, in order to resolve such disputes without undue complication or prolongation."

II. Authorization for the Association's Representative to Conduct the Lawsuit:

The Court then addressed the internal requirements for such an association to sue. It ruled that for the representative of an association without legal personality to pursue a sōyū confirmation lawsuit concerning property belonging to all members, the representative must be authorized through the same procedures that the association's charter or rules require for the disposal of such property (e.g., a resolution of the general meeting). The reasoning was:

"A final and binding judgment rendered in such a sōyū confirmation lawsuit extends its effect to all members. If the iriai association loses the case, it brings about a result factually equivalent to having disposed of the sōyū right of all members. Furthermore, the scope of the representative authority possessed by the representative of an iriai association varies for each association and cannot be assumed to naturally extend to all judicial or extra-judicial acts."

In this specific case, the record showed that X1 Association was indeed an association without legal personality and its representative (the head of the association) had, prior to filing the suit, obtained approval through a general meeting resolution, as required by its charter for property disposal. Thus, this authorization requirement was met.

III. Standing of an Individual Member (X2) to Sue for Registration Transfer:

Regarding X2's claim, the Supreme Court held that if an association without legal personality, through its established internal procedures, designates an individual member to be the registered titleholder of property that is held in sōyū by all its members, that designated member (even if not the association's official representative) has the standing to sue in their own name for registration procedures concerning that property. The Court reasoned:

"The necessity for an iriai association without legal personality to take such measures arises because it cannot effect registration in the name of the iriai association itself. Even if, instead of designating a representative with a fixed term as the registered titleholder and changing the ownership registration upon each change of representative, the iriai association separately designates an appropriate member as the owner on the register, such registration cannot be said not to fulfill the function of public notification. Such a member can become the registered titleholder for the benefit of all members. When such measures are taken, it is to be understood, in line with the parties' intentions, that the said member is entrusted by the iriai association to become the registered titleholder and is also granted the authority to pursue litigation for registration procedures."

The Court found that X2 had been designated as the titleholder for the Property by a unanimous resolution of X1 Association's general meeting before the suit was filed, and therefore X2 possessed the necessary standing.

Ultimately, the Supreme Court found that the High Court had erred in its interpretation and application of the law by denying standing to both X1 Association and X2, and remanded the case for substantive review.

Unpacking Iriai Rights and Associations Without Legal Personality

This judgment delves into concepts central to Japanese property and procedural law:

- Iriai-ken and Sōyū: These terms refer to traditional forms of communal resource management and ownership. Iriai-ken are typically rights of common usage (e.g., collecting firewood, foraging, pasturing animals) over specific lands, often held by the members of a local village community. Sōyū is a form of collective ownership associated with such rights, where the property belongs to the group as a whole. Unlike typical co-ownership (kyōyū), individual members in a sōyū relationship do not have distinct, divisible shares that they can freely sell or encumber. Rights are tied to membership in the community and are governed by long-standing local customs and rules.

- Association Without Legal Personality (kenri nōryoku naki shadan): This is a group that functions as an organization with a representative, rules, and assets, but has not incorporated as a legal entity (like a company or an incorporated association). Article 29 of the Japanese Code of Civil Procedure (formerly Article 46) grants such associations the capacity to sue and be sued in their own name (party capacity, tōjisha nōryoku). The District Court had recognized X1 Association as such an entity.

Key Legal Developments from the Judgment

The 1994 Supreme Court decision brought several important developments:

- Expanded Suing Options for Sōyū Confirmation: Prior to this ruling, a 1966 Supreme Court precedent had established that lawsuits for the confirmation of sōyū rights were "inherently necessary co-litigation," meaning all rightholders had to join as plaintiffs. This could be a significant practical barrier if even one member was unwilling or unable to participate. The 1994 judgment provided a crucial alternative by allowing the iriai association itself (if it met the criteria for an association without legal personality) to file such a suit as the plaintiff. This did not necessarily abolish the old rule but added a more practical method. (It's worth noting that if the group does not qualify as an association without legal personality, the old rule requiring all members to sue jointly would still apply. Later, a 2008 Supreme Court case further eased procedural hurdles by allowing such a suit even if not all iriai members were plaintiffs, provided non-consenting members were joined as defendants to ensure their participation in the litigation.)

- Clarification on Internal Authorization: The judgment stressed that for the association's representative to litigate such fundamental collective rights, the authorization process must be equivalent to that required for disposing of the property itself. This ensures that the decision to engage in litigation that could result in the loss of collective rights is taken with due seriousness and proper internal governance. While the authorization in this case was by unanimous consent of X1's members, the Court's general statement on the required authorization refers to the association's rules for property disposal, which might not always require unanimity.

- Practicality in Property Registration: Since an association without legal personality cannot typically have real estate registered in its own name, the Court's affirmation that a designated individual member can hold the registered title and sue for registration procedures is a pragmatic solution. This extended previous caselaw that had allowed the representative of such an association to hold title in their name as a trustee, now permitting any member duly designated by the association to do so.

- The "Litigation Trust" Concept and Scope of Judgment: Academic commentary suggests that when an association without legal personality sues concerning rights that are in sōyū of its members, it often acts as a form of "litigation trustee" (soshō tantō) for those members. The Supreme Court's statement that the effect of a final judgment in such a case extends to all members of the association aligns with this understanding, potentially grounded in provisions like Article 115(1)(ii) of the Code of Civil Procedure, which deals with the scope of a judgment's effect on those whose rights are managed by a party to the litigation.

Implications and Continued Relevance

This Supreme Court decision has had lasting importance for the many traditional communities across Japan that continue to manage common lands and resources under iriai systems. It provides a more accessible legal pathway for these communities to protect their collective rights against external challenges or internal disputes. By recognizing the standing of the iriai association, the Court streamlined what could otherwise be an exceedingly complex and potentially unmanageable litigation process. The judgment reflects an effort to adapt modern legal procedures to the unique, group-oriented nature of traditional Japanese collective property rights, striving for a balance between respecting historical customs, ensuring fair representation of community interests, and promoting efficient dispute resolution.

Conclusion

The May 31, 1994, Supreme Court judgment is a significant affirmation of the legal capacity of traditional Japanese communities to act collectively in court to protect their iriai rights. By allowing iriai associations with recognized organizational structures to sue for confirmation of sōyū rights, and by clarifying the standing of designated members in registration matters, the Court provided vital tools for the preservation of these unique and historically important forms of communal landholding in Japan. The decision underscores the judiciary's role in interpreting and applying legal principles in a manner that is both procedurally sound and responsive to the diverse forms of property ownership and social organization existing within society.