Collective Consumer Redress in Japan (2023 Amendments): How the Two-Stage System Impacts Businesses

TL;DR

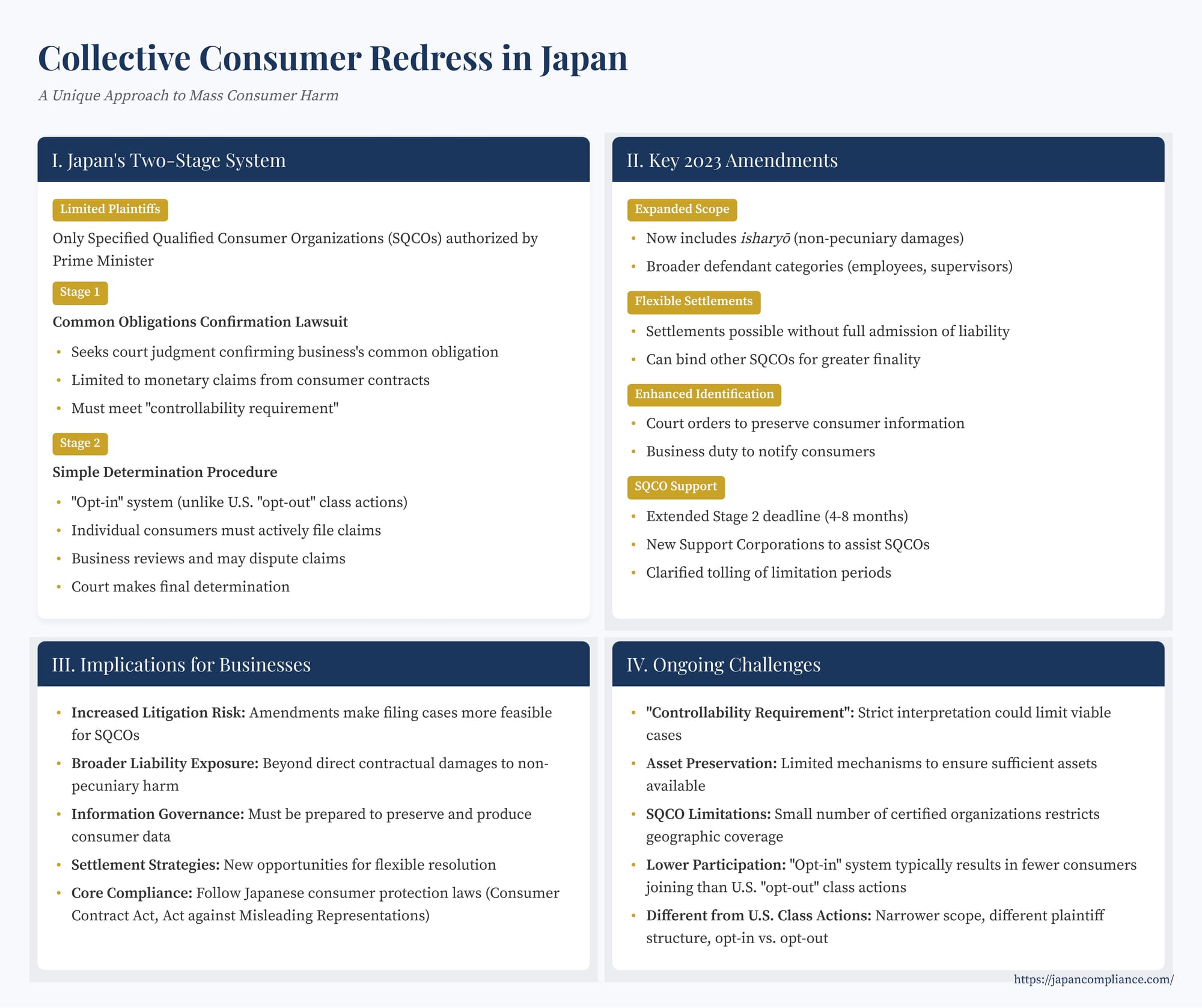

Japan’s collective consumer redress system is a two-stage, opt-in mechanism run by government-certified consumer organizations. The 2023 amendments widen claim scope (including non-pecuniary damages), broaden defendant categories, lengthen deadlines and create support bodies—making lawsuits more feasible. Businesses should tighten consumer-law compliance, prepare for early data preservation orders, and consider flexible settlements.

Table of Contents

- Introduction: A Unique Approach to Mass Consumer Harm

- Overview of Japan's Two-Stage Collective Redress System

- Key 2023 Amendments to Enhance the System

- Practical Implications for Businesses Serving Japanese Consumers

- Ongoing Challenges and Future Outlook

- Conclusion

Introduction: A Unique Approach to Mass Consumer Harm

When defective products, misleading advertisements, or unfair contract terms cause widespread financial harm to numerous consumers, seeking individual redress through the courts can be impractical or economically unviable. Many legal systems have developed mechanisms for collective action to address such situations. While the United States is well-known for its opt-out class action system driven primarily by private attorneys, Japan has established a distinct, two-stage procedure involving certified consumer organizations.

Introduced in 2013 and effective from 2016, the "Act on Special Measures Concerning Civil Court Proceedings for the Collective Redress for Property Damage Incurred by Consumers" (commonly known as the Consumer Court Procedure Special Measures Act or shōhisha saiban tetsuzuki tokureihō) aimed to provide a path for recovering small-value, mass-generated consumer damages. However, the initial uptake of this system was extremely limited, prompting significant legislative amendments enacted in 2022 and effective from 2023. These changes aimed to enhance the system's usability and effectiveness, potentially increasing its relevance for businesses operating in the Japanese consumer market.

This article provides an overview of Japan's unique collective redress system, details the key amendments designed to bolster its functionality, discusses the practical implications for businesses (including US companies serving Japanese consumers), and highlights ongoing challenges.

Overview of Japan's Two-Stage Collective Redress System

Japan's system differs markedly from US class actions. It operates in two distinct stages and relies exclusively on specific government-certified consumer organizations to initiate proceedings.

1. Eligible Plaintiffs: Specified Qualified Consumer Organizations (SQCOs)

Only a limited number of consumer organizations certified by the Prime Minister as "Specified Qualified Consumer Organizations" (特定適格消費者団体 - tokutei tekikaku shōhisha dantai, or SQCOs) are permitted to file the first-stage lawsuit. These organizations must meet stringent requirements regarding their expertise, governance, financial stability, and track record in consumer protection. As of early 2023, only a handful of SQCOs existed, concentrated primarily in the Kanto (Tokyo area) and Kansai (Osaka area) regions, plus Hokkaido, leaving significant parts of the country without local representation capable of initiating these actions. This limited number has been a major factor in the system's low usage rate.

2. Stage 1: Common Obligations Confirmation Lawsuit (Kyōtsū Gimu Kakunin Sosho)

An SQCO initiates the process by filing a "Common Obligations Confirmation Lawsuit" against the business allegedly responsible for the widespread harm. The purpose of this lawsuit is not to determine the damages owed to individual consumers, but rather to seek a court judgment confirming that the business owes a common obligation to a defined group (class) of consumers based on common factual and legal grounds.

- Scope of Claims: The types of claims eligible for this procedure are limited by the Act. They primarily involve monetary claims arising from consumer contracts, such as demands for performance, cancellation refunds, damages for non-performance, warranty claims, and unjust enrichment. Certain tort claims related to consumer contracts (e.g., concerning misrepresentation or failure to provide adequate explanation under the Consumer Contract Act, or liability for defects) are also included.

- Objective: The SQCO must demonstrate that the business has obligations towards numerous consumers arising from substantially similar factual and legal causes. A key hurdle is the "controllability requirement" (shihaisei no yōken), demanding that the existence and content of the individual consumers' rights can be determined without needing extensive examination of each consumer's unique circumstances in this first stage.

- Outcome: If the court confirms the common obligation, the judgment binds the business with respect to all consumers falling within the scope defined by the judgment.

3. Stage 2: Simple Determination Procedure (Kan'i Kakutei Tetsuzuki)

Following a final and binding judgment confirming the common obligation in Stage 1, the SQCO must apply to the court (within a specified timeframe) to commence the Stage 2 "Simple Determination Procedure."

- Consumer Opt-In: This stage operates on an opt-in basis. Affected consumers who wish to seek recovery must actively file a claim with the court within a designated period after public notice is given. This contrasts sharply with the US opt-out system where class members are automatically included unless they exclude themselves.

- Claim Filing: Consumers submit documentation to support their claim and the amount of damages sought.

- Business Response: The business reviews the filed claims and can either accept them or dispute their validity or amount.

- Court Determination: The court makes a final determination on each filed claim, typically based on the documentary evidence. If the business disputes a claim, more formal proceedings might occur, but the process is designed to be simpler and quicker than ordinary litigation.

- Distribution: Once claims are finalized, the SQCO typically assists in distributing the recovered funds to the successful consumer claimants, potentially deducting approved expenses and remuneration.

Key 2023 Amendments to Enhance the System

The low utilization of the system led to the 2022 amendments (effective 2023), designed to address several perceived weaknesses:

1. Expanded Scope of Recoverable Damages:

- Inclusion of Isharyō (Solatium/Non-Pecuniary Damages): A significant limitation of the original Act was its exclusion of claims for non-pecuniary damages (often termed isharyō, covering pain and suffering or emotional distress). The amendments now permit SQCOs to include claims for isharyō if these claims arise from the same factual circumstances that give rise to the eligible property damage claims (e.g., claims under the Consumer Contract Act). Claims for isharyō based solely on intentional torts by the business are also now included. This expansion, reflected in the Act's name change to cover "Property Damage, Etc.", allows for more comprehensive recovery in certain situations, such as cases involving discriminatory practices alongside financial harm (e.g., refunds of unfairly charged fees plus solatium for the underlying discrimination). However, it remains narrower than the broad scope of damages often recoverable in US class actions.

- Expanded Categories of Defendants: Originally, Stage 1 lawsuits were primarily limited to the business entity that was the direct counterparty to the consumer contract. The amendments broaden the potential defendants to include employees or supervising entities under theories of tort liability or vicarious liability (shiyōsha sekinin), provided their actions (or supervisory failures) involved intent or gross negligence and caused the consumer harm related to a consumer contract. This allows SQCOs to pursue recovery even if the direct contracting party is insolvent, provided the fault standards can be met against related individuals or entities.

2. Increased Flexibility in Stage 1 Settlements:

- Settlements Beyond Obligation Confirmation: Under the old interpretation, settling a Stage 1 case likely required the business to formally admit the common obligation. The amendments explicitly allow for more flexible settlements. Businesses and SQCOs can now agree on a settlement amount (和解金債権 - wakai-kin saiken) to be paid to a defined group of consumers without the business necessarily admitting the underlying common obligation in full.

- Binding Effect: Settlements reached in Stage 1, including agreements not to pursue further litigation on the matter, can now be structured to bind not only the participating SQCO but also other SQCOs, providing greater finality for businesses. This increased flexibility aims to incentivize negotiated resolutions.

3. Enhanced Consumer Identification and Notification:

- Early Preservation of Consumer Information: A major practical difficulty was identifying and notifying affected consumers, especially if the business destroyed relevant records before Stage 2 commenced. The amendments empower courts, during Stage 1, to issue orders requiring businesses to preserve and disclose lists or information pertaining to the potential class of consumers (Article 9).

- Business's Duty to Notify: The burden of notifying consumers in Stage 2 is no longer solely on the SQCO. The amendments place obligations on the defendant business to provide known consumer information to the SQCO and to directly notify consumers whose contact information it possesses about the commencement of the Stage 2 procedure (Articles 28, 30).

- Government Information Dissemination: The scope of information publicly announced by the government regarding the proceedings has also been expanded (Article 95).

4. Reducing Burdens on SQCOs:

- Extended Stage 2 Deadline: The non-extendable one-month deadline for an SQCO to initiate Stage 2 after a Stage 1 judgment was often impractically short. The amendments extend this period to four months, with the possibility of court-approved extension up to eight months (Article 16).

- Creation of Support Corporations: A new system establishes "Consumer Organization Litigation Support Corporations" (消費者団体訴訟等支援法人 - shōhisha dantai訴訟tō shien hōjin). These are certified non-profit entities (NPOs, general incorporated associations/foundations) tasked with assisting SQCOs. Their functions can include handling consumer notifications, managing and distributing recovered funds under SQCO commission, providing information to the public, and potentially receiving settlement funds or donations to support SQCO activities (Articles 98, 108, 89). This aims to alleviate the significant administrative and financial burdens faced by SQCOs.

- Streamlined Certification & Collaboration: The amendments also aim to simplify the administrative requirements for SQCO certification and renewal, and explicitly permit collaboration between different SQCOs and Qualified Consumer Organizations (QCOs, which can bring injunctive actions but not collective redress suits) (Articles 72, 81).

5. Clarified Tolling of Statutes of Limitation:

- Protection for Individual Claims: The amendments clarify that the statute of limitations for an individual consumer's claim is tolled from the date the SQCO files the Stage 1 lawsuit. Crucially, this tolling effect remains even if the Stage 1 suit is later withdrawn or dismissed, or if the SQCO fails to initiate Stage 2 or withdraws from it. Affected consumers are given a six-month window following such events to file their own individual lawsuits, benefiting from the tolling period (Article 68). This prevents consumers from losing their rights due to procedural issues outside their control.

6. Restricted Access to Stage 2 Records:

- Privacy Protection: Recognizing the risk of misuse (e.g., by fraudulent actors targeting identified victims), access to court records from the Stage 2 Simple Determination Procedure, which contain lists and details of consumer claimants, is now restricted. Only the parties involved (SQCO, business) and third parties who can demonstrate a legitimate legal interest are permitted to inspect these records (Article 54).

Practical Implications for Businesses Serving Japanese Consumers

The 2023 amendments strengthen Japan's collective redress system, and businesses, including US companies, should be aware of the potential implications:

- Increased Litigation Risk: While the number of SQCOs remains small, the amendments are designed to make initiating and pursuing collective actions more feasible. The expanded scope of claims (including isharyō), broader defendant categories, and support mechanisms for SQCOs could lead to an increase in Stage 1 lawsuits over time.

- Broader Liability Exposure: Potential liability is no longer confined to direct contractual damages caused by the company itself. Businesses may face collective claims incorporating non-pecuniary damages or claims stemming from the actions (if grossly negligent or intentional) of employees or related supervising entities.

- Information Governance: The provisions allowing courts to order the preservation and disclosure of consumer information early in the process highlight the need for robust data management practices and compliance with Japan's Act on the Protection of Personal Information (APPI). Businesses must be prepared to identify and potentially produce relevant consumer data if faced with a Stage 1 lawsuit.

- Settlement Strategies: The enhanced flexibility for Stage 1 settlements offers businesses new potential pathways for resolving collective disputes without necessarily admitting the full common obligation. However, negotiating these settlements will require careful consideration of the terms, the scope of consumers covered, and the binding effect on other SQCOs.

- Emphasis on Core Compliance: The most effective risk mitigation strategy remains strong compliance with underlying Japanese consumer protection laws, such as the Consumer Contract Act and the Act against Unjustifiable Premiums and Misleading Representations (dealing with false advertising). Avoiding business practices that could generate widespread, small-value harm is key to preventing Stage 1 actions in the first place.

Ongoing Challenges and Future Outlook

Despite the amendments, several challenges inherent in the Japanese system remain:

- The "Controllability Requirement": As noted in legal commentary, the requirement that common obligations and subsequent damages be determinable without extensive individualized inquiries remains a potential bottleneck. If courts interpret this requirement too strictly, it could bar meritorious cases involving complex damages calculations (even if based on common factors), potentially limiting the system's effectiveness, particularly in cases involving deceptive practices or diverse consumer impacts. How courts apply this standard post-amendment will be critical.

- Asset Preservation: Ensuring that defendant businesses have sufficient assets available to satisfy judgments or settlements at the end of the lengthy two-stage process remains a concern. While SQCOs can seek provisional remedies like asset attachments, this can be difficult and costly. Unlike some systems where administrative agencies might have powers to freeze assets, Japan's system currently lacks robust, built-in mechanisms for preserving defendant assets specifically for collective redress claims.

- SQCO Capacity and Coverage: The fundamental reliance on a small number of certified SQCOs continues to limit the system's geographic reach and capacity. While the new Support Corporations may help alleviate financial and administrative burdens, fostering the growth and sustainability of more SQCOs across Japan is likely necessary for the system to realize its full potential.

- Comparison to US Class Actions: The Japanese system remains fundamentally different from US class actions. Its opt-in nature for consumers in Stage 2 typically results in much lower participation rates and smaller overall recoveries compared to opt-out classes. The limitation to SQCOs as plaintiffs contrasts with the US system driven by private law firms. The scope of recoverable damages, even with the recent expansion, is generally narrower than in the US. Businesses facing potential mass claims should understand these key structural differences.

Conclusion

Japan's unique two-stage collective consumer redress system has been significantly revamped through recent amendments aimed at making it a more potent tool for addressing widespread consumer harm. By expanding the scope of claims and defendants, increasing settlement flexibility, enhancing consumer notification, and providing support for the initiating SQCOs, the revised Act potentially lowers the barriers to bringing collective actions.

For businesses operating in Japan, particularly those serving a large consumer base, awareness of this strengthened system is essential. While its usage may still be developing compared to jurisdictions like the US, the potential for SQCO-led litigation over issues ranging from contractual breaches to misleading practices has increased. Proactive compliance with consumer protection laws, coupled with robust information management and a readiness to engage constructively if faced with a collective claim, remain the most effective strategies for navigating this evolving legal landscape.

- Japan's Approach to Consumer Protection in the Digital Age

- Key Changes in Japan's 2023 Premiums and Representations Act Revision

- Public Interest Litigation in Japan: A New Avenue for Corporate Accountability

- Consumer Group Lawsuit System (消費者団体訴訟制度)

- What is the Consumer Group Lawsuit System? (消費者団体訴訟制度とは)

- COCoLiS Portal – Consumer Group Lawsuit System