Cohabiting Heirs and Inherited Property: Japan's Supreme Court on Post-Inheritance Use

Date of Judgment: December 17, 1996

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench, Case No. Heisei 5 (o) No. 1946 (Partition of Co-owned Land and Building, etc. Claim Case)

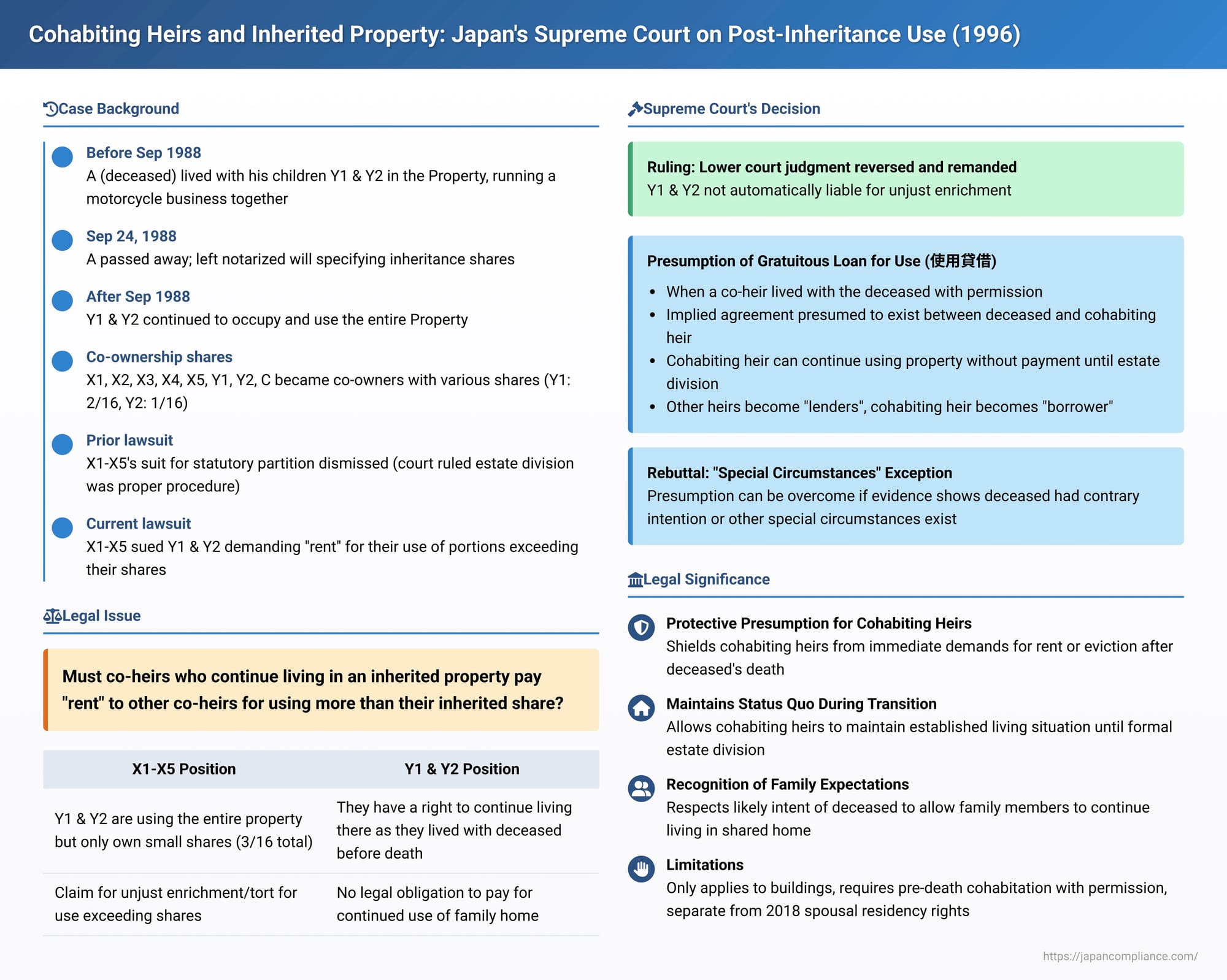

When an individual passes away, the property they leave behind is often inherited by multiple heirs, leading to a period of co-ownership until the estate is formally divided. A common and often complex situation arises when one or more heirs were already living in an inherited property with the deceased prior to their death and continue to reside there afterwards. This raises a critical question: what is the legal basis for their continued occupancy, and are they obligated to pay rent to the other co-heirs for using the entirety of the property?

The Supreme Court of Japan addressed this nuanced issue in a significant decision on December 17, 1996. This ruling established a key presumption regarding the continued use of inherited residential property by cohabiting heirs, offering a degree of stability during the often-transitional period before formal estate division.

Facts of the Case

The case involved a dispute over an inherited property (referred to as "the Property," consisting of a building and its land) previously owned by the deceased, A.

- The Deceased and Occupying Heirs: A had lived in the Property with his children, Y1 and Y2 (the appellants). They were not just family members residing together; they also ran the family business of repairing and selling motorcycles from the Property. After A’s death on September 24, 1988, Y1 and Y2 continued to occupy and use the entire Property.

- Other Heirs and Legatees: The other parties involved were X1, X2, X3, X4, and X5 (the appellees). A had left a notarized will specifying the inheritance shares and making a proportional universal legacy to X1. Another heir, B, subsequently transferred their inheritance share to Y1.

- Resulting Co-ownership Shares: After these dispositions, the Property was co-owned with the following approximate shares: X1 held 2/16; X3 held 2/16; X4 held 2/16; X2 held 3/16; X5 held 3/16; Y1 held 2/16; Y2 held 1/16; and C (another co-owner) held 1/16. The estate division had not yet been completed.

- The Claim: X1-X5 sued Y1 and Y2, demanding payment equivalent to rent for the portion of the Property exceeding Y1 and Y2's own shares. This claim was based on theories of unjust enrichment or tort, alleging that Y1 and Y2 were benefiting from using the entire property without legal cause, thereby causing a loss to the other co-owners.

- Previous Action: An earlier lawsuit by X1-X5 against Y1, Y2, and C for a statutory partition of the co-owned property (共有物分割 - kyōyūbutsu bunkatsu) had been dismissed. The court had ruled that the division of inherited property should be handled through the specific process of estate division (遺産分割 - isan bunkatsu).

Lower Courts' Rulings

Both the court of first instance and the High Court (the "lower appellate court" mentioned in the judgment) found in favor of X1-X5. Their reasoning was that a co-owner who occupies and uses the entirety of a co-owned property, thereby exceeding their own share, is generally liable to the other co-owners for unjust enrichment, unless there is a specific agreement to the contrary. Y1 and Y2 appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision

The Supreme Court overturned the High Court's judgment regarding the part where Y1 and Y2 were found liable and remanded the case for further proceedings. The Court's reasoning introduced a significant presumption in cases of this nature.

The core of the Supreme Court's rationale was as follows:

- Presumption of a Gratuitous Loan for Use (使用貸借 - shiyō taishaku):

When a co-heir has been living with the deceased in an inherited building with the deceased's permission from before the commencement of inheritance (i.e., before the deceased's death), a crucial presumption arises. The Court stated that, in the absence of "special circumstances" (特段の事情 - tokudan no jijō), it is presumed that an implied agreement existed between the deceased and the cohabiting heir. - Terms of the Implied Agreement: This presumed agreement entails that the cohabiting heir would be allowed to continue using the building gratuitously (無償で - mushō de) even after the deceased's passing, until the ownership of the building is finally determined through the estate division process.

- Legal Relationship After Death: Upon the deceased's death, this implied agreement transforms into a gratuitous loan for use contract (使用貸借契約 - shiyō taishaku keiyaku) concerning the building. The other co-heirs (who inherit the deceased's status) effectively become the lenders, and the cohabiting heir becomes the borrower. This loan for use continues at least until the estate division is completed.

- Rationale for the Presumption: The Supreme Court reasoned that this presumption aligns with the "ordinary intentions" (通常の意思 - tsūjō no ishi) of both the deceased and the cohabiting heir. Given that the building served as the cohabiting heir's home and their residence was based on the deceased's explicit or implicit permission, it's natural to infer that the deceased would have intended for the heir to continue living there under the same conditions (i.e., without charge) pending the final settlement of the estate. This grants the cohabiting heir the right to use the entire building during this interim period.

- "Special Circumstances" as a Rebuttal: This presumption is not absolute. It can be rebutted if "special circumstances" are proven to exist. Such circumstances might include evidence that the deceased had expressed a contrary intention (e.g., that rent should be paid, or the heir should vacate).

- Application to the Present Case:

In this case, Y1 and Y2 were A's heirs and had lived with A in the Property as part of A's family. Therefore, the Supreme Court found it reasonable to presume that a gratuitous loan for use agreement concerning the building had been established between A and Y1/Y2.

If Y1 and Y2's continued occupation and use of the building were based on such a gratuitous loan for use, then their benefit would have a legal basis. Consequently, a claim for unjust enrichment by X1-X5 would be unfounded because the enrichment would not be "without legal cause."

The Supreme Court concluded that the High Court erred in immediately finding unjust enrichment without sufficiently examining the potential existence of this presumed gratuitous loan for use agreement. The case was therefore remanded to the High Court to further deliberate on whether such an agreement should be presumed and whether any "special circumstances" existed that might rebut this presumption.

Legal Principles and Significance

This 1996 Supreme Court judgment carries substantial weight in Japanese inheritance law:

- Establishes a Protective Presumption: It creates a default position that favors the cohabiting heir who lived with the deceased with permission. This protects such heirs from immediate demands for rent or eviction by other co-heirs during the potentially sensitive and uncertain period following a death and preceding formal estate division.

- Focus on Implied Intent: The decision emphasizes the likely, albeit unstated, intentions of the deceased and the cohabiting heir, rooting the legal solution in the typical understanding and expectations within a family cohabitation context.

- Mechanism of Gratuitous Loan for Use: By characterizing the post-inheritance relationship as a gratuitous loan for use, the Court provides a clear legal framework for the cohabiting heir's continued, rent-free occupancy.

- Maintains Status Quo (Temporarily): The ruling facilitates a degree of stability by allowing the cohabiting heir to continue their established living situation until the estate is formally divided, at which point the ultimate ownership and rights of use will be definitively settled.

- Flexibility through "Special Circumstances": The inclusion of the "special circumstances" rebuttal ensures that the presumption does not lead to unfair outcomes if evidence shows the deceased had a different intention or if other overriding factors are present.

Scope and Limitations of the Judgment

The commentary accompanying this case in legal analyses highlights several points regarding its scope:

- Applicability to Inherited Buildings: The presumption directly applies when the asset in question is a building that is part of the co-owned inherited estate. It does not automatically extend to other types of inherited property (e.g., vacant land, financial assets).

- Not Applicable if Not Co-owned Estate Property: If the building is not part of the co-owned inherited estate available for division—for instance, if it was specifically bequeathed to one heir (特定遺贈 - tokutei izō) or subject to a will directing it to be succeeded by a specific heir (特定財産承継遺言 - tokutei zaisan shōkei igon)—this presumption would not apply, at least not directly in the same manner.

- Requirement of Deceased's Permission and Cohabitation: The heir must have been cohabiting with the deceased with the deceased's permission. If the cohabitation was without permission, or if the individual occupying the property was not an heir who had been living with the deceased (e.g., a third-party tenant without a formal lease after the deceased's death), this specific presumption would not apply. (However, a subsequent Supreme Court decision in 1998 did apply similar reasoning to protect a surviving common-law spouse's use of co-owned property. )

- Distinction from Later Spousal Residency Rights: The 2018 reforms to Japan's Civil Code introduced statutory rights for surviving spouses, including a "short-term spousal residential right" (配偶者短期居住権 - haigūsha tanki kyojūken). While this 1996 judgment was a conceptual forerunner for such rights, the statutory spousal rights operate differently. For example, the short-term spousal right does not necessarily require prior cohabitation with the deceased in all circumstances outlined in the statute and is a statutory right not dependent on a presumed intention of the deceased in the same way. For cohabiting heirs who are not spouses, this 1996 Supreme Court judgment's presumption of a gratuitous loan for use remains relevant.

- Duration of the Gratuitous Use: The presumed gratuitous loan for use lasts "at least until the estate division is completed." If the estate division process becomes significantly prolonged, the practical implications might require further consideration, though the judgment itself does not delve into mechanisms for early termination by the "lender" heirs beyond standard contract principles like breach by the "borrower" heir.

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court's 1996 decision reflects a pragmatic and empathetic approach to a common scenario in Japanese family life and inheritance. By presuming an implied agreement for gratuitous continued use, the Court provides a legal underpinning that respects the established living arrangements and the likely intentions of the deceased, thereby offering a measure of security to cohabiting heirs during the interim period before the final division of the inherited estate. This ruling continues to be a vital reference point for understanding the rights and obligations of co-heirs concerning the use of inherited residential property in Japan.