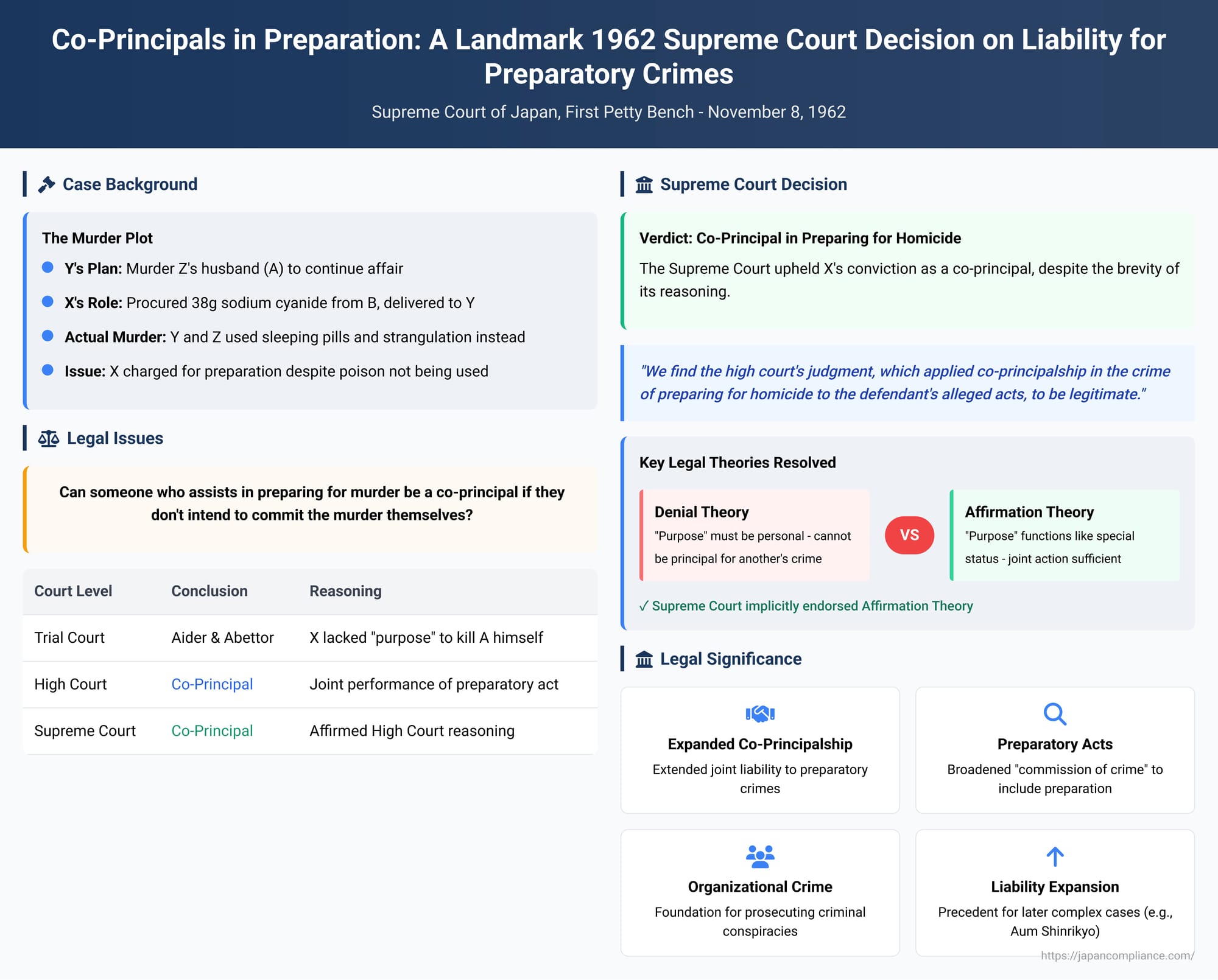

Co-Principals in Preparation: A Landmark 1962 Supreme Court Decision on Liability for Preparatory Crimes

Decision of the First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan, November 8, 1962

(Case No. 1962 (A) No. 88: Case of Preparing for Homicide)

Introduction

On November 8, 1962, the Supreme Court of Japan issued a terse yet profoundly influential decision that reshaped the understanding of criminal liability for acts preceding the commission of a crime. The case revolved around the charge of preparing for homicide and addressed a fundamental question: can an individual who assists in preparing for a murder, but does not intend to carry out the killing themselves, be held liable as a co-principal? By affirming the lower court's finding of co-principalship, the Supreme Court set a crucial precedent, expanding the scope of joint criminal liability into the preparatory stages of an offense and clarifying the legal status of those who knowingly facilitate another's criminal plans.

Factual Background

The Murder Plot and the Defendant’s Role

The case originated from a murder plot devised by an individual named Y. Y was having an affair with a person named Z and planned to murder Z's husband, A. To carry out this plan, Y sought the help of his cousin, the defendant X, asking him to procure potassium cyanide, a deadly poison.

X agreed to the request. He obtained sodium cyanide from another individual, B, and delivered approximately 38 grams of it, wrapped in vinyl, to Y. X's role was confined to this preparatory act of acquiring and supplying the means for the murder. He did not participate further in the planning, nor did he intend to be present at or participate in the actual killing.

The Unfolding of the Crime

In a turn of events, Y did not use the sodium cyanide provided by X. Instead, Y conspired with Z to murder A through different means. They administered sleeping pills to A and then strangled him to death.

The Legal Conundrum

Although the poison X supplied was never used, his actions were undeniably in furtherance of Y's homicidal plan. This raised a complex legal issue. X had knowingly and willingly performed a preparatory act for a murder. Under Article 201 of the Penal Code of Japan, "a person who, for the purpose of committing a crime [of homicide], makes a preparation thereof" is subject to punishment. But could X, who had no intention of killing A himself, be considered a principal offender in this preparatory crime? Or was his liability something lesser, like an aider and abettor? And what was the significance of the fact that the specific means he provided were ultimately abandoned? These questions placed the judiciary in the challenging position of defining the boundaries of liability in the gray area between thought and action.

The Diverging Opinions of the Lower Courts

The journey of the case through the lower courts revealed deep divisions in judicial interpretation regarding preparatory crimes and complicity.

The Trial Court: Aiding and Abetting Preparation

The Nagoya District Court, as the court of first instance, found X guilty as an aider and abettor to the crime of preparing for homicide. The court's reasoning was twofold:

- Denial of Principalship for "Preparation for Another": The court held that to be a principal in a preparatory crime, the actor must possess the "purpose" of committing the ultimate crime (in this case, murder) themselves. Since X only intended to help Y, he lacked the personal purpose required to be a principal. This is a classic articulation of the argument against recognizing "preparation for another's crime" (tanin yobi) as a form of principalship.

- Affirmation of Accessoryship: However, the court reasoned that since preparing for homicide is itself a distinct crime, it is possible to aid and abet this "preparatory act." By providing the poison, X had facilitated Y's crime of preparation, making him liable as an accessory.

The Appellate Court: Co-Principalship in Preparation

The Nagoya High Court, on appeal, overturned the trial court's reasoning and reached a different conclusion. It convicted X as a co-principal in the crime of preparing for homicide. The appellate court's logic was more intricate:

- Preparation as an "Act of Commission": The court asserted that a preparatory act, while preliminary, constitutes the "act of commission" for the specific crime of preparation. Therefore, individuals who "jointly" perform this act can be considered co-principals under Article 60 of the Penal Code.

- Rejection of Accessoryship to Preparation: In a striking move, the High Court argued that accessoryship (aiding and abetting) to a preparatory crime should be considered non-punishable unless explicitly stipulated by law. It expressed concern that since preparatory acts are themselves broad and ill-defined, allowing for the punishment of those who merely assist in these acts would risk an undue expansion of criminal liability, potentially penalizing behavior too remote from the actual harm.

- X as a Co-Principal: The court concluded that X's actions were not merely peripheral assistance but an integral part of Y's preparatory conduct. By undertaking the crucial task of procuring the poison, X was not a mere helper but a joint actor in the preparation. His contribution was essential to the shared plan, thus elevating his role from an aider to a co-principal.

This created a peculiar legal situation: the High Court deemed aiding and abetting preparation too broad to be punishable, yet found the defendant guilty of the more serious charge of being a co-principal in the very same act. The case was then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Terse but Definitive Ruling

The Supreme Court's decision on November 8, 1962, is notable for its brevity. The main text of the ruling formally dismisses the appeal on procedural grounds, stating that the defense's arguments did not constitute valid reasons for a final appeal.

However, embedded within this formulaic dismissal is a parenthetical phrase that contains the entire substantive weight of the judgment:

"...(We find the high court's judgment, which applied co-principalship in the crime of preparing for homicide to the defendant's alleged acts, to be legitimate.)"

With this single sentence, the Supreme Court unequivocally endorsed the conclusion of the Nagoya High Court. It affirmed that X's conduct amounted to co-principalship in the preparation of homicide. While the Court did not provide its own detailed reasoning, its stamp of approval on the High Court's decision established a binding precedent with far-reaching implications.

Analysis and Broader Implications

The 1962 ruling was a watershed moment in Japanese complicity law. Its impact can be analyzed through several key legal doctrines that it touched upon.

1. Affirming Co-Principalship in Preparatory Crimes

The most direct consequence of the decision was the official recognition that the concept of co-principalship could extend to the preparatory stage of a crime. Article 60 of the Penal Code defines co-principals as those who "act jointly in the commission of a crime." This ruling effectively broadened the interpretation of "commission of a crime" to include the "commission" of a preparatory offense. It confirmed that individuals could be held jointly and fully liable for a crime that was never completed, and for which they only performed preliminary acts.

2. The Unresolved Problem of "Accessoryship to Preparation"

While the Supreme Court affirmed the co-principalship conviction, it remained silent on the High Court's view that aiding and abetting preparation should be non-punishable. This left a theoretical gap. However, by validating the more serious charge, the ruling signaled that significant involvement in preparation could and should be met with severe liability. In practice, this encouraged prosecutors and lower courts to construe preparatory assistance as co-principalship whenever possible, effectively bypassing the unresolved debate over accessoryship.

3. The Implicit Approval of "Preparation for Another" as Principalship

The core of the case rested on the "preparation for another's crime" (tanin yobi) issue. Can someone like X, who prepares for a murder he does not intend to commit himself, be a principal offender? The crime of preparing for homicide (Article 201) requires a specific "purpose" of committing murder.

- The Denial Theory: This theory, adopted by the trial court, argues that the "purpose" must be personal. One cannot be a principal based on another's purpose. Such an actor could, at most, be an accessory.

- The Affirmation Theory: This theory posits that the "purpose" requirement functions like a "special status" under Article 65 of the Penal Code. This article generally provides that a non-status offender who collaborates with a status offender can also be held liable as a co-principal. By this logic, X (the non-status offender without the direct "purpose") could become a co-principal by acting jointly with Y (the status offender who possessed the purpose).

By upholding X's conviction as a co-principal, the Supreme Court implicitly sided with the affirmation theory. It signaled that lacking a personal intent to execute the final crime does not preclude an individual from being a full partner—a co-principal—in the preparatory crime itself.

4. The Legacy: A Gateway to Broader Complicity

This 1962 decision laid the theoretical groundwork for a significant expansion of complicity in the decades that followed. By establishing that joint action in the preparatory phase was sufficient for co-principalship, it opened the door for courts to later recognize liability based on "conspiracy to prepare" alone, even with minimal physical involvement. Later landmark cases, such as those related to the Aum Shinrikyo cult's plot to produce sarin gas, would build upon this precedent to hold planners and organizers liable as co-principals for vast criminal enterprises, based on their role in the preparatory conspiracy. The 1962 decision can be seen as the first crucial step in that direction.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1962 decision in the case of preparing for homicide, though brief, was monumental. It navigated the treacherous legal terrain between mere thought and criminal action, establishing that the bonds of co-principalship could be forged long before a crime reaches its final stage. By holding an individual who only procured poison for another liable as a co-principal, the Court expanded the frontiers of criminal responsibility. It affirmed that in the world of planned crime, those who knowingly and essentially contribute to the preparatory phase are not mere assistants but partners in the offense. This ruling remains a cornerstone of Japanese criminal law, shaping how courts assess the culpability of the many actors who may play different but crucial roles in the commission of a crime.