Co-ownership and Correcting the Record: A Japanese Supreme Court Decision on False Property Registrations

Date of Judgment: July 11, 2003

Case Name: Claim for Cancellation of Registration of Full Share Transfer, etc.

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

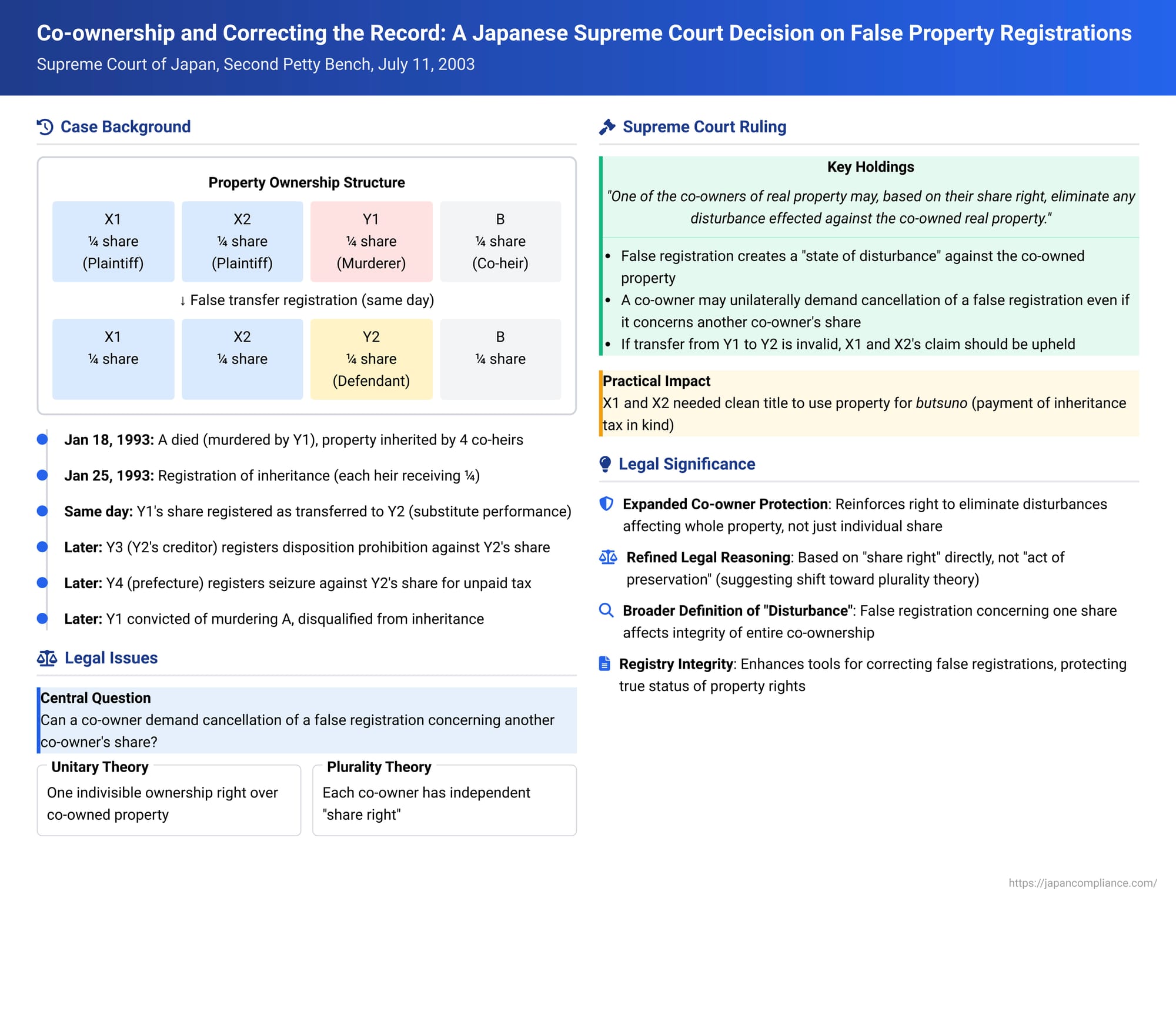

The realm of co-owned property often gives rise to complex legal questions, particularly when the official property register does not align with the true ownership status. A pivotal Japanese Supreme Court decision handed down on July 11, 2003, addressed a critical issue: to what extent can one co-owner act to rectify a false registration concerning another co-owner's share, especially when that registration grants apparent rights to an entity with no legitimate claim? This case delves into the foundational principles of co-ownership rights and the remedies available to co-owners to protect their common asset from disturbances caused by such "paper" claims.

The Factual Tapestry: A Disputed Inheritance

The case originated from a tragic series of events involving a wealthy individual, A, who passed away on January 18, 1993. A was survived by four children: X1, X2 (the plaintiffs/appellants in the Supreme Court), Y1 (a defendant), and B, who all became co-heirs to A's substantial assets, including several plots of land (referred to collectively as the "Property").

Following A's death, events unfolded rapidly:

- Initial Inheritance Registration: On January 25, 1993, the Property was registered in the names of all four heirs—X1, X2, Y1, and B—with each holding a one-quarter share, reflecting their statutory inheritance portions.

- Problematic Share Transfer: On the very same day, Y1's entire one-quarter share in the Property was purportedly transferred to Y2 (a defendant/appellee). This transfer was registered as being made due to a daibutsu bensai (substitute performance or accord and satisfaction), suggesting Y1 used the land share to settle a debt owed to Y2.

- Y1's Disqualification: It later transpired that A had been murdered by Y1. Y1 was subsequently prosecuted and, after the High Court's decision in the civil matter, was convicted of murder and arson. This conviction rendered Y1 a sōzoku kekkakusha (a person disqualified from inheritance) under Article 891, Item 1 of the Civil Code. Consequently, Y1's own children became heirs by subrogation (daishū sōzoku) pursuant to Article 887, Paragraph 2 of the Civil Code.

- Further Encumbrances on Y2's Purported Share: After Y2 acquired the registration of Y1's share, further claims attached to it. Y3, a creditor of Y2, obtained a provisional disposition (shobun kinshi kashobun tōki) prohibiting the disposal of Y2's registered share. Additionally, Y4, the local prefectural government, registered a seizure (sashiosae tōki) against Y2's purported share for unpaid real estate acquisition tax owed by Y2.

- The Plaintiffs' Predicament: X1 and X2 found themselves in a difficult position. They were faced with inheritance taxes exceeding two billion yen. The false registration in Y2's name, and the subsequent encumbrances by Y3 and Y4, created a cloud on the title, preventing X1 and X2 from using the Property for butsuno—a system in Japan allowing payment of inheritance tax in kind using the inherited real estate.

To resolve this, X1 and X2 initiated legal proceedings. Their primary claim was against Y2, seeking the cancellation of the registration transferring Y1's share to Y2, arguing that the underlying transfer was invalid. They also sought confirmation that the Property was co-inherited by them and requested Y3 and Y4 to consent to the cancellation of Y2's registration.

The Legal Labyrinth: From District Court to the Supreme Court

The case navigated through the Japanese judicial system:

- The District Court: The first instance court found in favor of X1 and X2. It determined that the daibutsu bensai agreement between Y1 and Y2 was invalid, potentially due to being a fictitious transaction or contrary to public order and good morals. Crucially, the District Court held that X1 and X2, as co-owners, could demand the cancellation of Y2's (now deemed invalid) registration as an "act of preservation" (hozon kōi) under the Civil Code, which allows a co-owner to take actions to preserve the co-owned property. Only Y2 appealed this decision.

- The High Court: The appellate court (Nagoya High Court) took a different view. It overturned the District Court's decision regarding the cancellation, ruling that X1 and X2 could not demand the cancellation of the entire registration of Y1's share transfer to Y2 based on their co-ownership rights as an act of preservation. The High Court reasoned that even if the transfer from Y1 to Y2 was invalid and Y2's registration was false, the share rights of X1 and X2 were not directly infringed. This led X1 and X2 to seek a review by the Supreme Court.

The central question before the Supreme Court was: Can a co-owner, based on their own share right, demand the cancellation of a registration concerning another co-owner's share when that registration is substantively false and vests apparent title in someone with no actual rights to the property?

The Supreme Court's Adjudication (July 11, 2003)

The Supreme Court of Japan reversed the High Court's decision and remanded the case back to the Nagoya High Court for further proceedings.

The Court's reasoning was direct and rooted in established principles of property law:

- Co-owner's Right to Eliminate Disturbance: "One of the co-owners of real property may, based on their share right, eliminate any disturbance effected against the co-owned real property."

- False Registration as a Disturbance: "Where a false registration of a share transfer has been made, it can be said that a state of disturbance against the co-owned real property has arisen due to said registration."

- Right to Demand Cancellation: "Therefore, a co-owner may unilaterally demand that a person who has no substantive right at all to the co-owned real property, yet has obtained a registration of a share transfer, undertake the procedures for cancellation of said share transfer registration."

The Supreme Court cited two of its previous rulings (Supreme Court, May 10, 1956, and Supreme Court, July 22, 1958) to support this position. It also distinguished another case (Supreme Court, April 24, 1984) as being factually different because in that instance, the registration was partially valid for the co-owner named in the registration.

Crucially, the Supreme Court stated: "Based on the above, if the transfer of the share of the Property from Y1 to Y2 is invalid, the primary claim of the appellants [X1 and X2] should be upheld."

The High Court had not definitively ruled on the validity of the transfer from Y1 to Y2. Its decision was based on the premise that even if it were invalid, X1 and X2 couldn't seek its cancellation. The Supreme Court found this legal reasoning to be flawed. Therefore, the case was sent back for the High Court to determine the validity of the Y1-Y2 share transfer. If found invalid, X1 and X2's claim for cancellation of Y2's registration should be granted.

Understanding Co-ownership in Japanese Law

To fully appreciate the Supreme Court's decision, it's helpful to understand the theoretical underpinnings of co-ownership (kyōyū) in Japanese law. When multiple individuals own a single property, their legal relationship to that property has been conceptualized in primarily two ways:

- The Unitary Theory (tan'itsu setsu): This theory posits that there is only one, indivisible ownership right over the co-owned property. This singular right is sometimes referred to as a "co-ownership right" (kyōyūken). Each co-owner is seen as holding a fractional interest or portion of this single, overarching right. Historically, the drafters of the Japanese Civil Code and the Real Property Registration Act are thought to have leaned towards this perspective.

- The Plurality Theory (fukusū setsu): In contrast, this theory suggests that each co-owner possesses an independent right, often termed a "share right" (mochibunken), which is conceptually similar to a sole ownership right but pertaining to their specific share. Co-ownership, under this view, is an aggregation or a bundle of these distinct, individual share rights. The plurality theory gained significant traction in academic circles from the Taisho era (1912-1926) onwards and eventually established itself as the prevailing view among scholars.

While some legal textbooks suggest that the practical outcomes under both theories might often be similar, the choice of theory has historically influenced discussions, especially in the context of civil procedure, such as determining when all co-owners must sue or be sued together (mandatory co-litigation).

Judicial Evolution: Co-owners' Rights to Rectify Registrations

Japanese courts have, over time, developed a body of case law addressing how co-owners can protect their rights. The theoretical basis for these actions has often been a subject of discussion.

- Claims for Confirmation of Rights: Earlier precedents distinguished between lawsuits concerning the entire "co-ownership right" (which often required all co-owners to participate) and those concerning an individual's "share right" (where a single co-owner could sue).

- Claims for Removal of Disturbance (Exclusion of Interference): When a third party interfered with the co-owned property, traditional case law, often reflecting the unitary theory, allowed a single co-owner to sue for the removal of the entire disturbance, frequently justifying this as an "act of preservation" (hozon kōi) for the common property (as per Civil Code Article 252, which, in its modern form after revisions, continues to address acts of preservation). Academics favoring the plurality theory, however, argued that a co-owner could demand the removal of a disturbance affecting "the whole of the co-owned property" based directly on their share right and the right to use the property in proportion to their share (as per Civil Code Article 249, Paragraph 1), without needing to invoke the concept of an "act of preservation."

- Claims for Return of Property:

- If a third party had a contractual obligation to return the property to all co-owners, a single co-owner could demand its return, often based on the idea that the claim was an "indivisible claim" (fukabun saiken).

- If the claim was against someone occupying the property without any right, the courts also allowed a single co-owner to demand its return, typically framed as an "act of preservation." Again, scholars advocating the plurality theory proposed a basis in Article 249, Paragraph 1.

- Claims Related to Property Registration:

- When the Registered Party Has No Substantive Right: The Supreme Court had previously held (in the Showa 31 and Showa 33 decisions cited in the present Heisei 15 judgment) that a single co-owner could demand the complete cancellation of a registration if the registered party had no substantive right to the property at all. These cases often involved situations where the entire property was incorrectly registered.

- When the Registered Party is Another Co-owner (and the Registration is Partially Valid): A different line of cases (including the Showa 59 decision also mentioned in the Heisei 15 judgment as distinct) addressed situations where the registration was in the name of a fellow co-owner but was, for instance, incorrect as to the share amount. In such scenarios, other co-owners could typically only demand a "correction registration" (kōsei tōki) to rectify their own shares, as the existing registration was valid to the extent of the registered co-owner's actual share.

The Significance of the Heisei 15 (2003) Supreme Court Judgment

The July 11, 2003, Supreme Court decision fits into the first category of registration claims: the allegation was that Y2, the registered party for Y1's former share, had no substantive right to that share because the underlying transfer from Y1 was void. The judgment carries several important implications:

- Reinforcement of Co-owner's Right Against Baseless Registrations: The decision strongly reaffirms the principle that an individual co-owner has the standing to sue for the cancellation of a registration held by someone who possesses no underlying legal right to the share, even if the false registration pertains to another co-owner's share. This empowers co-owners to take action to clear the title of the co-owned property.

- A Potential Nuance in Legal Reasoning: The Absence of "Act of Preservation": Notably, the Supreme Court's reasoning in this 2003 judgment bases the co-owner's right to seek cancellation directly on their "share right" (mochibunken) and the need to eliminate a "disturbance" to the co-owned property. The term "act of preservation" (hozon kōi), which was central to the District Court's reasoning and common in older precedents for such actions, is conspicuously absent from the Supreme Court's own rationale in this specific judgment.This linguistic choice is significant. Previous rulings that allowed a single co-owner to demand cancellation of an entirely baseless registration (like the Showa 31 and 33 decisions) had been interpreted by some academics as being based on the "act of preservation" doctrine, even though those judgments themselves sometimes used the term "share right." Scholars had criticized the necessity of invoking "act of preservation" if the claim could be founded directly on the nature of the share right itself, particularly if one subscribes to the plurality theory of co-ownership. The 2003 judgment's focus on the "share right" as the basis for eliminating a disturbance, without mentioning "act of preservation," might suggest an implicit acknowledgment of these academic critiques or a subtle evolution in the Court's conceptual framing. However, it remains ambiguous whether this signals a definitive shift away from the unitary theory towards the plurality theory in all co-ownership contexts, or if it's a refinement specific to cases involving the cancellation of entirely baseless registrations.

- Defining "Disturbance" and "Infringement" Broadly: A critical aspect of this case was how the "disturbance" or "infringement" of the plaintiffs' (X1 and X2) rights was construed. Their own shares were correctly registered. The problem stemmed from the false registration of Y1's former share in Y2's name. The Supreme Court accepted that this false registration constituted a disturbance to the co-owned property as a whole. The specific harm articulated by the plaintiffs was their inability to use the property for butsuno (payment of inheritance tax in kind) due to the cloud on title created by Y2's registration and the subsequent encumbrances. This indicates that a "disturbance" can arise not just from direct interference with a co-owner's own registered share, but also from a false registration concerning another share if it prejudices the other co-owners' ability to fully utilize or dispose of the property according to their rights.Some subsequent lower court decisions have reportedly interpreted this Heisei 15 judgment as establishing a more general principle: that any false registration concerning one co-owner's share inherently constitutes an infringement or disturbance to the share rights of the other co-owners, even without such specific detrimental consequences as the butsuno issue. This broader interpretation suggests that the mere existence of a false entry in the register regarding any part of the co-owned property can be seen as undermining the integrity and certainty of all co-owners' rights.

- The Procedural Context: The discussion of unitary versus plurality theories of co-ownership was historically linked to procedural questions, particularly whether all co-owners needed to be party to a lawsuit (mandatory co-litigation). Modern procedural law theory in Japan has evolved, with the view gaining prominence that such procedural requirements are determined not solely by substantive law theories but also by "litigation policy" considerations aimed at ensuring fair and efficient dispute resolution