Co-Owned Shares, Company Consent, and Voting Rights: Interpreting Japan's Companies Act Article 106 Proviso

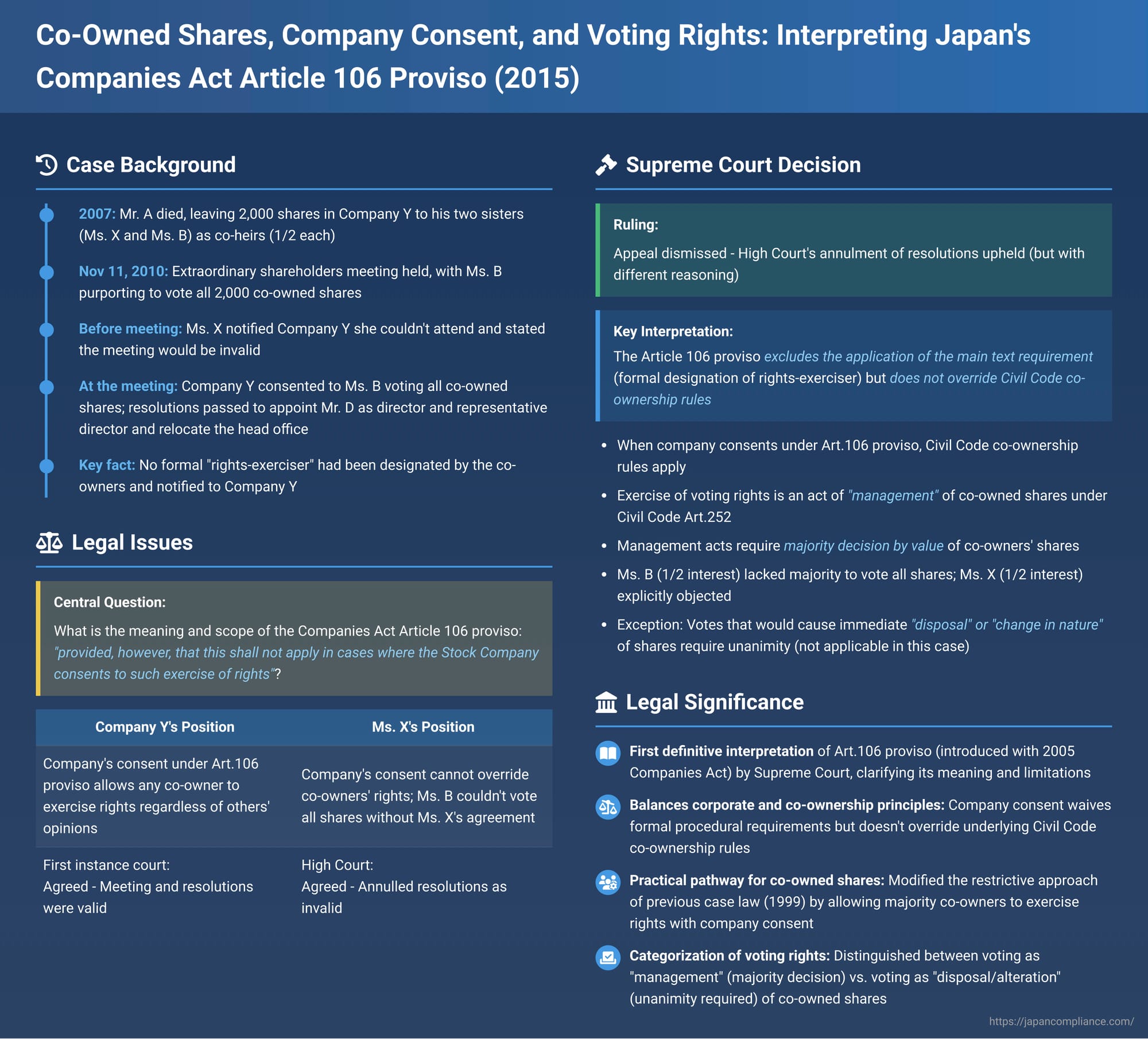

When company shares are held by more than one person—a common scenario following an inheritance where shares pass to multiple heirs—Japanese company law provides a specific procedure for how shareholder rights associated with those co-owned shares are to be exercised. Generally, the co-owners must designate one person from among them (or a third party) to act as the "rights-exerciser" and notify the company of this designation. Only this designated person can then exercise the rights. However, Article 106 of the Companies Act also includes a proviso: "provided, however, that this shall not apply in cases where the Stock Company consents to such exercise of rights." The meaning and scope of this "company consent" proviso were the subject of a key Japanese Supreme Court decision on February 19, 2015, which clarified how shareholder rights for co-owned stock can be exercised when a formal rights-exerciser hasn't been designated.

The Facts: A Family Inheritance and a Disputed Shareholder Meeting

The case involved Company Y, a tokurei yūgen kaisha (a type of special limited company under transitional rules, treated similarly to a stock company for these purposes). Company Y had 3,000 issued shares. Of these, 2,000 shares ("the Co-owned Shares") were originally held by Mr. A. Upon Mr. A's death in 2007, these 2,000 shares were jointly inherited by his two sisters, Ms. X (the plaintiff) and Ms. B, each receiving a one-half statutory inheritance portion. As Mr. A's estate had not yet been formally divided, these 2,000 shares were in a state of quasi-co-ownership (junkyōyū) between Ms. X and Ms. B.

An extraordinary shareholders' meeting of Company Y was held on November 11, 2010 ("the Meeting"). At this Meeting, Ms. B, one of the co-owning sisters, purported to exercise all the voting rights attributable to the entire block of 2,000 Co-owned Shares. Mr. C, who held the remaining 1,000 shares of Company Y, also participated and voted his shares.

Ms. X, the other co-owning sister, had received a notice convening the Meeting. However, she informed Company Y that she would be unable to attend due to inconvenience and, significantly, stated that any meeting held would be invalid. She did not attend the Meeting.

Despite Ms. X's absence and her expressed objection, the Meeting proceeded. Based on the votes cast by Ms. B (for the 2,000 Co-owned Shares) and Mr. C (for his 1,000 shares), the following resolutions ("the Resolutions") were passed:

- To appoint Mr. D as a director of Company Y.

- To appoint Mr. D as the representative director of Company Y.

- To amend the articles of incorporation to change Company Y's registered head office location and to relocate the head office.

A crucial fact was that, for the Co-owned Shares, Ms. X and Ms. B had not formally designated a person to exercise shareholder rights, and no notification of such a designee had been provided to Company Y, as required by the main text of Companies Act Article 106. However, Company Y, at the Meeting, consented to Ms. B exercising the voting rights for all 2,000 Co-owned Shares. This consent was presumably given based on the proviso to Article 106.

Ms. X subsequently filed a lawsuit against Company Y, seeking the annulment of the Resolutions. She argued that the method by which the Resolutions were passed violated laws and regulations (specifically, Companies Act Article 831, Paragraph 1, Item 1), primarily because Ms. B's exercise of voting rights for the entirety of the Co-owned Shares was improper.

The Legal Question: The Meaning of "Company Consent" in Article 106 Proviso

The lower courts arrived at different conclusions regarding the effect of Company Y's consent:

- Yokohama District Court, Kawasaki Branch (First Instance): Dismissed Ms. X's claim. It held that since Company Y had consented to Ms. B's exercise of voting rights under the proviso of Companies Act Article 106, there was no illegality in Ms. B voting the Co-owned Shares.

- Tokyo High Court (Appellate Court): Reversed the first instance decision, ruling in favor of Ms. X and annulling the Resolutions. The High Court interpreted the Article 106 proviso much more narrowly. It opined that the proviso only permits a company's consent to validate the exercise of rights (in the absence of a formally designated rights-exerciser under the main text of Article 106) if the co-owners have already consulted among themselves and reached a unified decision on how those rights should be exercised. Since Ms. X clearly opposed Ms. B's actions, there was no such unified decision. Therefore, Company Y's consent could not legitimize Ms. B's exercise of the votes. The High Court concluded that Ms. B's voting was improper, rendering the Resolutions defective.

Company Y appealed to the Supreme Court, arguing that the Article 106 proviso simply means that if the company consents, a specific co-owner can lawfully exercise the rights associated with co-owned shares, irrespective of an internal agreement (or lack thereof) among all co-owners.

The Supreme Court's Interpretation: Balancing Formalities and Co-ownership Principles

The Supreme Court, in its First Petty Bench judgment, dismissed Company Y's appeal, thereby upholding the High Court's decision to annul the Resolutions, though its reasoning differed in crucial aspects from that of the High Court.

1. Companies Act Article 106 Main Text as a "Special Rule" for Co-owned Shares:

The Court began by explaining that the main text of Companies Act Article 106 (requiring co-owners to designate a single rights-exerciser and notify the company) establishes a "special rule" regarding the method of exercising rights for co-owned shares. This special rule is permitted under Article 264, proviso, of the Civil Code, which allows for deviations from general Civil Code co-ownership rules if specifically provided for elsewhere (as in the Companies Act).

2. Interpreting the Article 106 Proviso ("unless the Company consents..."):

The Supreme Court then turned to the proviso of Article 106. It stated that the literal wording of the proviso—"provided, however, that this shall not apply in cases where the Stock Company consents to such exercise of rights"—means that if the stock company gives its consent, the application of the special rule found in the main text of Article 106 (i.e., the requirement for formal designation and notification of a rights-exerciser) is excluded.

3. Reversion to General Civil Code Rules on Co-ownership:

This interpretation led to a crucial next step: if the company's consent under the proviso sets aside the specific procedural requirements of Article 106's main text, then how is the exercise of rights for co-owned shares to be governed? The Supreme Court's answer was that the matter reverts to the general rules of co-ownership under the Civil Code.

4. Lawful Exercise of Rights Requires Compliance with Civil Code Co-ownership Rules:

Therefore, the Court concluded that even if a company consents under the Article 106 proviso to a particular co-owner exercising rights for co-owned shares (despite the lack of formal designation under the main text), that exercise of rights is not lawful if it does not comply with the relevant provisions of the Civil Code governing co-owned property.

5. Voting Rights as an Act of "Management" of Co-owned Shares (Civil Code Article 252):

The Supreme Court then considered how the exercise of voting rights for co-owned shares should be treated under the Civil Code. It held that the exercise of such voting rights, "unless there are special circumstances, such as where the exercise of said voting rights would immediately result in the disposition of the shares or a change in the nature of the shares," is to be considered an act of "management" (管理に関する行為 - kanri ni kansuru kōi) of the co-owned shares.

Under Article 252, main text, of the Civil Code, acts concerning the management of co-owned property are decided by a majority of the co-owners in accordance with the value of their respective shares.

6. Application to the Facts of the Case:

Applying these principles to the specific facts:

- Ms. B, who purported to exercise the voting rights for all 2,000 Co-owned Shares, held only a one-half (1/2) interest in those shares.

- Ms. X, who held the remaining one-half (1/2) interest, clearly did not consent to Ms. B's exercise of the votes; in fact, she had objected.

- Therefore, Ms. B's exercise of the voting rights was not decided by a majority of the co-owners' share values (as 1/2 is not "more than half"). It did not comply with the requirements of Civil Code Article 252.

- The specific resolutions passed at the Meeting (appointment of directors, appointment of a representative director, and changes to the head office location) were not found by the Court to constitute "special circumstances" that would immediately lead to the disposal of the Co-owned Shares or fundamentally alter their nature. Thus, they were acts of "management."

- Since Ms. B's exercise of voting rights was not in accordance with the Civil Code's rules on co-ownership, Company Y's consent under the Article 106 proviso could not render it lawful.

Consequently, the Supreme Court concluded that Ms. B's voting was improper. This meant the Resolutions were passed with unlawfully cast votes, making the method of resolution contrary to law. The High Court's decision to annul the Resolutions was therefore affirmed.

Key Implications of the Ruling

This 2015 Supreme Court decision is highly significant as it was the first to interpret the proviso of Companies Act Article 106, a provision introduced with the 2005 Companies Act whose precise meaning had been subject to debate.

- Clarification of the Proviso's Limited Scope: The ruling clarifies that company consent under Article 106 proviso does not give the company unlimited power to validate any co-owner's exercise of rights. Instead, it merely waives the formal procedural requirement of designating and notifying a single rights-exerciser as stipulated in the main text of Article 106.

- Primacy of Underlying Co-ownership Principles: Once the formal procedure is waived by company consent, the fundamental principles of co-ownership under the Civil Code (primarily, the majority rule for acts of management) come into play. The exercise of rights must still be legitimate under these general civil law rules.

- Impact on Previous Case Law: The PDF commentary suggests this ruling effectively modifies the understanding of a 1999 Supreme Court precedent (Heisei 11.12.14). Under the old Commercial Code (which lacked the proviso), the 1999 case held that if no rights-exerciser was designated, the company could not permit voting unless all co-owners acted jointly. The 2015 decision implies that now, under the Companies Act, if a majority of co-owners agree on exercising voting rights (e.g., in a particular way), the company can consent under the Article 106 proviso, and such voting would be lawful even if a minority of co-owners dissent. This provides a pathway for the majority of co-owners to act, which was more restricted under the 1999 ruling.

- Company Consent is Not a Blank Check: The decision makes it clear that a company cannot simply "pick a winner" among feuding co-owners by consenting to one co-owner's exercise of rights if that co-owner does not have the backing of a majority (by value) of the co-owned interests for acts of management.

The "Special Circumstances" Caveat for Voting: Management vs. Disposal/Alteration

The Supreme Court introduced an important caveat: the exercise of voting rights is considered an act of "management" (requiring a majority vote of co-owners' shares) unless "special circumstances" exist where the voting would immediately lead to the disposal of the shares or a change in their fundamental nature.

- If such "special circumstances" exist, the act of voting might be classified not as "management" but as an act of "disposal" (処分 - shobun) or "alteration" (変更 - henkō) of the co-owned property. Under Article 251 of the Civil Code, acts of disposal or alteration of co-owned property generally require the unanimous consent of all co-owners.

- Examples where voting might fall into this more stringent category could include resolutions on matters like mergers, company dissolution, share consolidation if it fundamentally alters the shares' value or rights, or other transformative corporate actions.

- In this specific case, the resolutions concerning director appointments and head office relocation were deemed by the Court to be acts of management, not triggering this higher threshold of unanimity. This distinction is critical for co-owners to understand when assessing how decisions about their co-owned shares can be made.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's February 19, 2015, judgment provides essential guidance on the interpretation of Companies Act Article 106, particularly its often-debated proviso. By clarifying that company consent under the proviso waives the formal designation procedure but does not override the fundamental Civil Code principles governing co-ownership, the Court struck a balance. It allows for a more flexible approach than requiring strict adherence to the formal designation process in all cases, provided the company consents. However, it ensures that this flexibility does not empower a single co-owner, or even the company itself, to disregard the collective will of the co-owners as determined by the majority principle for acts of management. This decision is crucial for navigating shareholder rights in the context of co-owned shares, especially in closely-held and family companies where inheritance can lead to complex shared ownership structures.