Clawing Back Profits from a Pyramid Scheme: Japan's Supreme Court on Trustee Powers vs. "Illegal Cause Benefit" Defense

Judgment Date: October 28, 2014

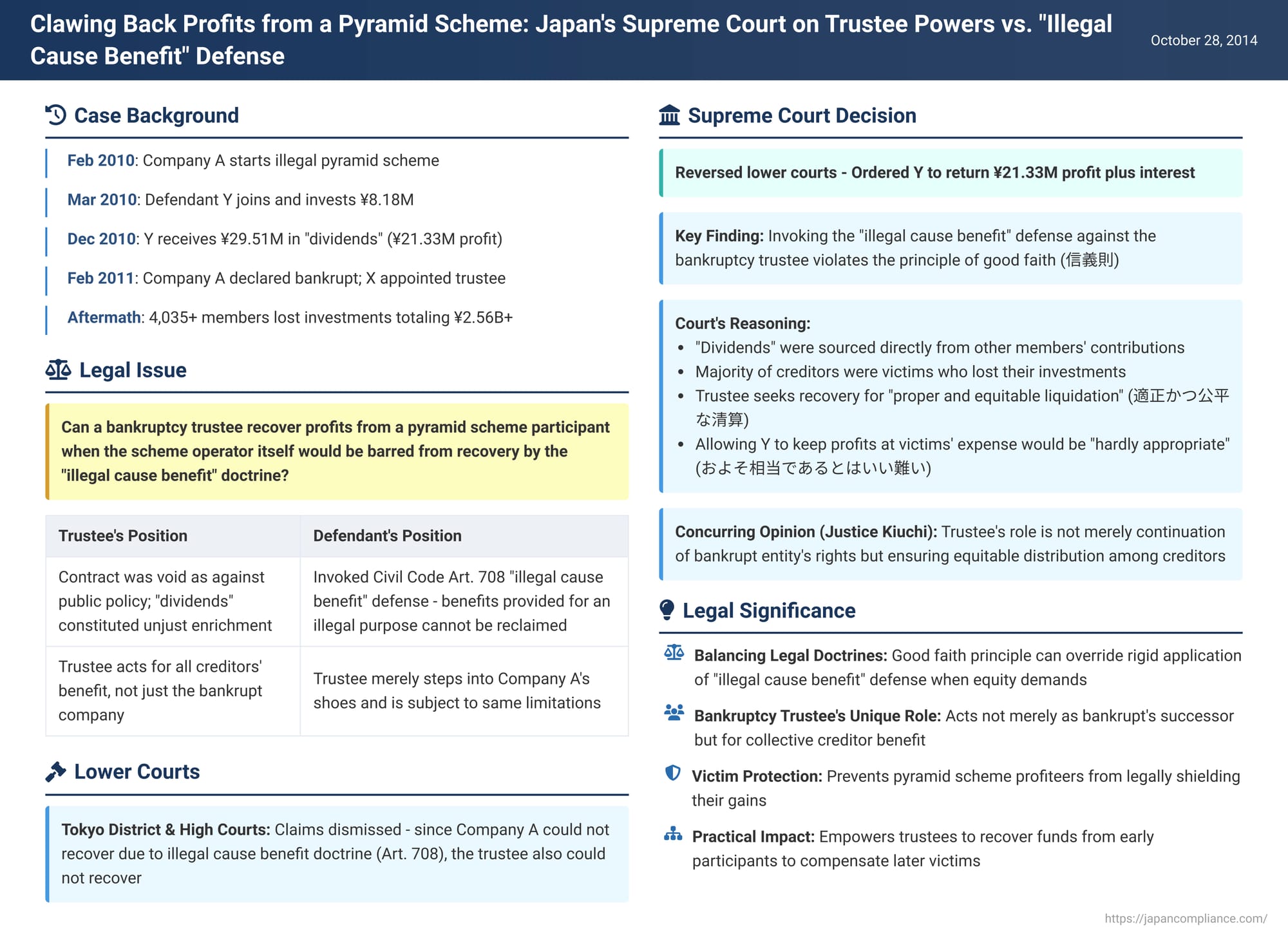

When a pyramid scheme collapses, it often leaves a trail of financial devastation, with many participants losing their investments while a few early entrants might walk away with significant profits. A crucial legal question then arises: can a bankruptcy trustee, appointed to manage the affairs of the collapsed scheme operator, recover these "winnings" from profiting members for redistribution to the wider pool of creditors, many of whom are victims? This issue was at the heart of a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan's Third Petty Bench on October 28, 2014 (Heisei 24 (Ju) No. 2007), which navigated the complex interplay between the principles of unjust enrichment, the "illegal cause benefit" doctrine, and the objectives of bankruptcy law.

The Pyramid Scheme and Its Inevitable Collapse

The case involved Company A, which, from around February 2010, initiated a business operation. This venture was structured such that capital contributions from new members were primarily used to pay "dividends" to existing members who had joined earlier. This is the classic hallmark of an illegal pyramid scheme (無限連鎖講 - mugen rensa kō), a practice prohibited under Japan's Act on Prevention of Endless Chain Schemes.

The defendant, Y, became a member of Company A's scheme in March 2010. By December 2010, Y had invested approximately ¥8.18 million and had received purported "dividends" amounting to roughly ¥29.51 million. This resulted in a net gain for Y of approximately ¥21.33 million.

Company A's scheme attracted at least 4,035 members and collected over ¥2.56 billion in investments before its inevitable implosion. On February 21, 2011, Company A was subjected to a bankruptcy commencement decision, and X was appointed as its bankruptcy trustee. A significant majority of the creditors in Company A's bankruptcy proceedings were members who had suffered financial losses in the scheme.

The Legal Challenge: Unjust Enrichment vs. the "Illegal Cause Benefit" Defense

The bankruptcy trustee, X, subsequently filed a lawsuit against Y. X argued that the contract between Y and Company A was void as being contrary to public policy and good morals (公序良俗違反 - kōjo ryōzoku ihan). Consequently, X claimed that the dividends Y received, particularly the net profit of approximately ¥21.33 million, constituted unjust enrichment and should be returned to the bankruptcy estate for distribution among creditors.

The Tokyo District Court and the Tokyo High Court (the lower courts) agreed with the trustee that the underlying contract was indeed void and that Y's receipt of the dividends therefore lacked a legal basis. However, both courts dismissed the trustee's claim. Their reasoning was anchored in Article 708 of the Japanese Civil Code, the "illegal cause benefit" (不法原因給付 - fuhō gen'in kyūfu) doctrine. This provision generally stipulates that a person who provides a benefit for an illegal cause cannot demand its return. Since Company A itself, having made the payments under an illegal pyramid scheme, would be barred by Article 708 from recovering the dividends from Y, the lower courts concluded that the bankruptcy trustee, X (who was, in this context, asserting Company A's right), was similarly barred. The trustee appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision: Equity and Good Faith Prevail Over a Rigid Defense

The Supreme Court reversed the decisions of the lower courts and ruled in favor of the bankruptcy trustee, X, ordering Y to return the net profit of approximately ¥21.33 million, along with interest.

The Court's reasoning was deeply rooted in principles of equity and good faith:

- Origin and Nature of the Funds: The Court emphasized that the "dividends" paid to Y were not generated from any legitimate business activity by Company A. Due to the inherent structure of the illegal pyramid scheme, these funds were sourced directly from the capital contributions made by other members, many of whom subsequently lost their investments.

- Plight of Other Members: A substantial portion of Company A's members were unable to recover their invested capital following the scheme's collapse. These victimized members constituted the majority of the creditors in the bankruptcy proceedings and had little to no other means of obtaining relief for their losses.

- The Bankruptcy Trustee's Objective: The Supreme Court highlighted that the bankruptcy trustee, X, was seeking the return of these funds not for the benefit of Company A (the perpetrator of the illegal scheme), but to facilitate a "proper and equitable liquidation" (適正かつ公平な清算 - tekisei katsu kōhei na seisan) of Company A's assets. The recovered funds would be distributed among all bankruptcy creditors, including the numerous members who had suffered losses. This objective, the Court found, was consistent with the principle of equity (衡平 - kōhei).

- Unconscionability of the Defense in This Context: The Court then addressed the application of Article 708. It reasoned that if Y were permitted to invoke the "illegal cause benefit" defense to refuse repayment to the bankruptcy trustee, it would effectively mean condoning Y's retention of unjust profits derived directly from the losses of other victimized members. Such an outcome, the Court declared, would be "hardly appropriate" (およそ相当であるとはいい難い - oyoso sōtō de aru to wa iigatai).

- Overriding Principle of Good Faith: Based on these considerations, the Supreme Court concluded that, under the specific circumstances of this case, for Y to assert the "illegal cause benefit" defense against the bankruptcy trustee's claim for return of the funds was impermissible under the principle of good faith and fair dealing (信義則 - shingisoku).

Justice Michiyoshi Kiuchi, in a concurring opinion, further elaborated on the distinct role of the bankruptcy trustee. He emphasized that the trustee's actions are not merely a continuation of the bankrupt entity's rights but are undertaken to fulfill the Bankruptcy Act's objectives of ensuring a proper and equitable liquidation of the debtor's assets and appropriately adjusting the rights among creditors and other interested parties. Justice Kiuchi pointed out that in most bankruptcies, especially those of entities like Company A, any assets recovered by the trustee become part of the bankruptcy estate for distribution to creditors, after covering procedural costs. It is exceedingly rare for any surplus to revert to the bankrupt entity itself; corporations typically cease to exist post-bankruptcy, and individuals often receive a discharge of their debts. Therefore, allowing the trustee to recover the funds does not equate to providing legal protection or benefit to the entity that orchestrated the illegal scheme. Instead, it serves to mitigate the losses of the victims and achieve a fairer distribution among all creditors. Denying recovery would allow those who profited from the illicit scheme to retain their gains at the direct expense of other victims.

Analyzing the Decision: Balancing Legal Doctrines and Equitable Outcomes

The Supreme Court's decision is significant for its nuanced approach to a complex legal problem. Article 708 of the Civil Code, embodying the "illegal cause benefit" principle, is generally understood to prevent a wrongdoer from using the courts to undo the consequences of their own illegal actions, akin to the "clean hands" doctrine in common law. A rigid application would suggest that if Company A couldn't recover, its trustee couldn't either.

However, the role of a bankruptcy trustee is unique. The trustee does not act solely as an agent of the bankrupt company but as an administrator of the bankruptcy estate for the collective benefit of all creditors. Their duties are prescribed by the Bankruptcy Act, which prioritizes the fair and equitable distribution of available assets.

The Supreme Court's reliance on the principle of good faith (信義則) to override the Article 708 defense in this specific context was crucial. This was not a blanket declaration that bankruptcy trustees are always exempt from the "illegal cause benefit" rule. Instead, the Court carefully considered the specific equities of the situation:

- The inherent nature of a pyramid scheme, which funnels money from later investors to earlier ones and the operator, ensuring widespread losses.

- The fact that the vast majority of creditors in Company A's bankruptcy were themselves victims of this scheme.

- The fact that any recovered funds would be used to compensate these victims and other legitimate creditors, not to benefit the defunct, wrongdoing Company A.

By focusing on these elements, the Supreme Court signaled that where a strict application of a legal doctrine (like Art. 708) would lead to a profoundly inequitable result—allowing some participants in an illegal scheme to profit at the direct expense of many other victims, especially within a bankruptcy framework designed for fair distribution—the overarching principle of good faith can be invoked to achieve a more just outcome. The decision recognized that the primary purpose of the recovery was not to restore the bankrupt entity but to provide a measure of redress to its creditors.

Broader Implications and Unanswered Questions

This ruling provides a strong precedent for bankruptcy trustees in Japan dealing with the aftermath of pyramid schemes and similar fraudulent operations that result in widespread losses among participants. It empowers trustees to pursue those who have profited from such schemes, even if the scheme operator itself would have been barred from doing so.

However, the fact-specific nature of the decision, grounded in the principle of good faith and the particular dynamics of a pyramid scheme bankruptcy, means its applicability to other contexts requires careful consideration:

- Other Types of Illegal Transactions: If a company goes bankrupt due to illegal activities where the creditors are not primarily direct victims of that specific illegality (e.g., ordinary business creditors of a company involved in some unrelated illegal act), the equitable considerations might differ, and the "good faith" override of Article 708 might not apply as readily.

- Non-Bankruptcy Scenarios: The Court's reasoning was heavily tied to the bankruptcy trustee's role in achieving an "equitable liquidation for all creditors." This strong emphasis may limit the direct applicability of this "good faith override" to individual creditor actions outside of a collective insolvency proceeding, such as attempts by a single creditor to use subrogation rights or attach assets. In such individual actions, the equitable balance and the potential for the original wrongdoer to indirectly benefit might be assessed differently.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's October 2014 decision represents a significant step in ensuring that the proceeds of illegal pyramid schemes can be reclaimed for the benefit of the scheme's victims within a bankruptcy context. By invoking the principle of good faith to prevent a profiting member from using the "illegal cause benefit" doctrine as a shield against the bankruptcy trustee's claim, the Court prioritized an equitable outcome for the collective body of creditors. This judgment underscores the judiciary's ability to flexibly apply legal principles to prevent unjust enrichment and to uphold the fairness objectives inherent in bankruptcy proceedings, particularly when dealing with schemes designed to defraud a large number of individuals.