Classroom Conduct and Legal Standards: Japan's Supreme Court on Teacher Discipline and Curriculum Guidelines

A First Petty Bench Ruling from January 18, 1990

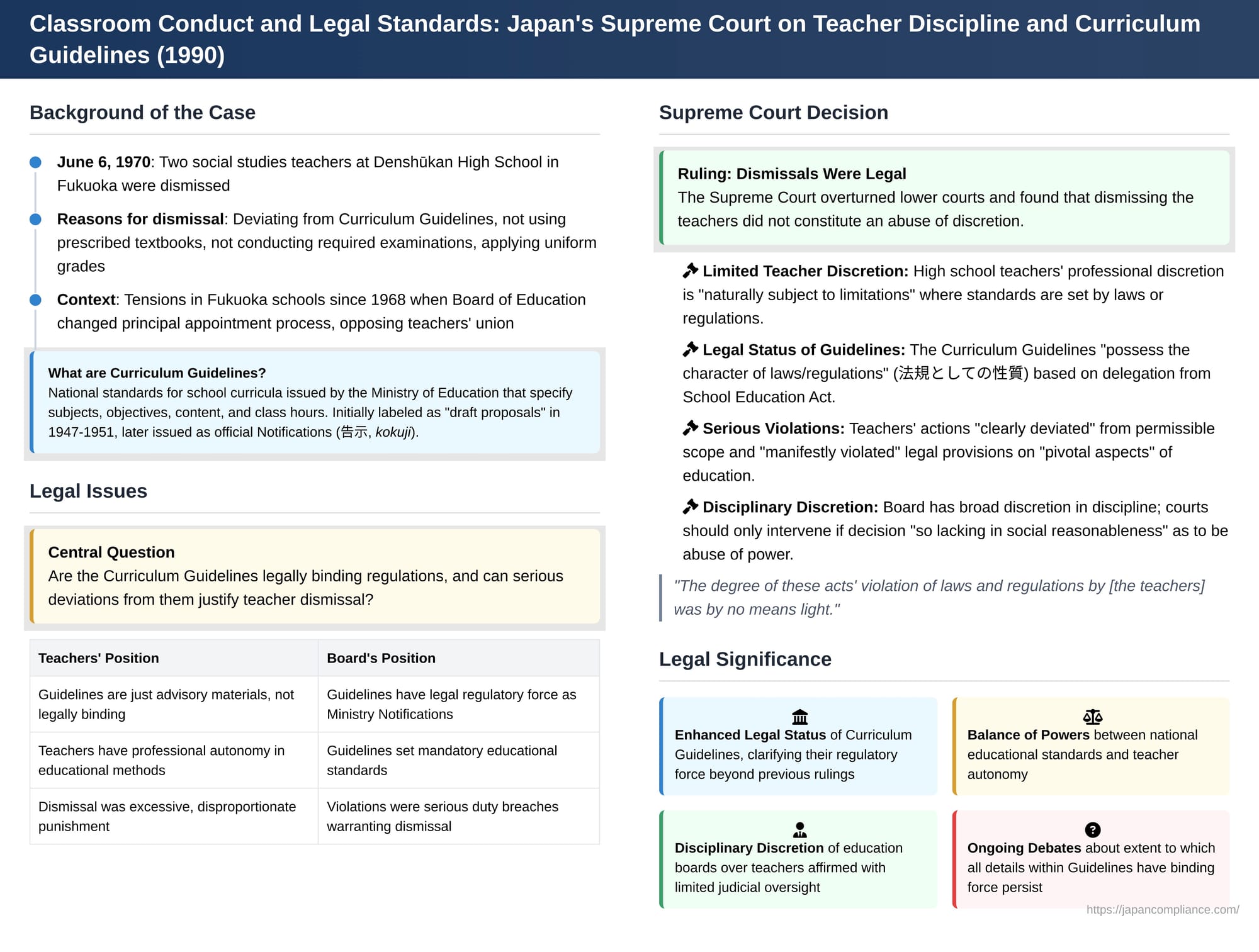

The balance between maintaining educational standards and respecting teachers' professional autonomy is a critical issue in any education system. National or regional curriculum guidelines often play a central role in setting these standards, but their precise legal force and the consequences for teachers who deviate from them can become subjects of intense legal dispute. A significant decision by the First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan on January 18, 1990 (Showa 59 (Gyo Tsu) No. 46), addressed these issues in the context of the disciplinary dismissal of public high school teachers in Fukuoka Prefecture for actions deemed contrary to official educational directives.

The Denshūkan High School Case: Teachers Dismissed

The case involved two social studies teachers, X2 and X3, at Denshūkan Prefectural High School (伝習館高等学校 - Denshūkan Kōtō Gakkō) in Fukuoka Prefecture. (A third teacher, X1, was also involved, but his case was separated and a judgment concerning him was issued on the same day). On June 6, 1970, the Fukuoka Prefectural Board of Education (Y, the defendant/appellant), which was the disciplinary authority, dismissed X2 and X3 from their positions.

The stated reasons for these disciplinary dismissals were serious:

- Conducting classroom instruction that deviated from the official Curriculum Guidelines (学習指導要領 - Gakushū Shidō Yōryō) issued by the Ministry of Education.

- Failing to use the prescribed textbooks for their subjects.

- Not conducting required student examinations (考査 - kōsa).

- Applying uniform grade evaluations (一律評価 - ichiritsu hyōka) to students, rather than assessing individual performance.

These actions were considered by the Board of Education to be violations of their duties as public servants and neglect of their professional responsibilities, falling under the grounds for disciplinary action stipulated in Article 29, paragraph 1, items (i) through (iii) of the Local Public Service Act (地方公務員法 - Chihō Kōmuin Hō).

The backdrop to these events was a period of tension in Fukuoka Prefecture's public high school system. Until around 1967, many schools, including Denshūkan High, had operated under a system where staff meetings (職員会議 - shokuin kaigi) effectively functioned as the highest decision-making bodies. Furthermore, it had become customary for the Prefectural Board of Education (Y) to appoint new school principals who were recommended or approved by the prefectural high school teachers' union (県高教組 - Ken Kōkyōso). However, in April 1968, the Board of Education unilaterally abandoned this custom and appointed several new principals, including the one at Denshūkan High School, without the union's recommendation. This led to significant opposition from the teachers' union, including organized efforts to refuse the new principals' assumption of their posts, creating a strained and often confrontational atmosphere within the schools.

The Legal Framework: Curriculum Guidelines and Teacher Duties

At the heart of this dispute lay the Curriculum Guidelines (学習指導要領 - Gakushū Shidō Yōryō). These are comprehensive documents issued by Japan's Ministry of Education (now the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology - MEXT) that outline the standards for school curricula for each educational level, from elementary through senior high school. They specify subjects to be taught, objectives, content, and standard class hours.

- The statutory basis for these Guidelines is found in the School Education Act (学校教育法 - Gakkō Kyōiku Hō) and its accompanying Enforcement Regulations (学校教育法施行規則 - Gakkō Kyōiku Hō Shikō Kisoku). For example, the School Education Act (then Article 20, now Article 33 for elementary schools, with analogous provisions for other levels) empowers the "supervisory agency" (then defined as the Minister of Education for certain matters) to determine matters concerning school curricula. The Enforcement Regulations (then Rule 25, now Rule 52 for elementary schools) further stipulated that school curricula "shall be based on the [respective level's] Curriculum Guidelines separately publicly notified by the Minister of Education as standards for curricula." These Guidelines are formally announced through official government Notifications (告示 - kokuji).

- The disciplinary actions against the teachers were taken under the Local Public Service Act, which allows for disciplinary measures against public employees for violations of laws and regulations, neglect of duty, or conduct unbecoming a public servant.

The Core Dispute: Legality of Dismissal and the Force of the Guidelines

X2 and X3 challenged the legality of their dismissals. The lower courts (Fukuoka District Court as the first instance and Fukuoka High Court as the second instance) reached similar conclusions for X2 and X3:

- They found that X2 had indeed violated the Curriculum Guidelines in his teaching, and that X3 had failed to conduct required examinations and had improperly applied uniform grade evaluations.

- However, both courts held that dismissing the teachers solely for these particular violations constituted an abuse of the Board of Education's disciplinary discretion. They therefore annulled the dismissal orders for X2 and X3. (X1's dismissal, based on different specific grounds, was upheld by the lower courts and ultimately by the Supreme Court in a separate judgment issued the same day).

The Prefectural Board of Education (Y) appealed the annulment of X2's and X3's dismissals to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision (January 18, 1990, for X2 and X3)

The Supreme Court's First Petty Bench overturned the Fukuoka High Court's decision that had favored X2 and X3. The Supreme Court found that the dismissals were lawful and did not constitute an abuse of discretion, thereby rejecting the teachers' claims.

Key Reasoning of the Supreme Court:

- Nature of High School Education and Limits on Teacher Discretion: The Court emphasized the unique characteristics of high school education. It noted that high schools have specific educational objectives to achieve within a prescribed period. Furthermore, teachers at this level still wield considerable influence over students who may not yet possess fully developed critical faculties or significant choice in their instructors. Given these factors, the Court found it necessary for the State to establish standards for educational content and methods to maintain a certain level of quality and achieve educational goals. Crucially, the Court stated that where such standards are established by laws or regulations (which would include the Curriculum Guidelines, as discussed below), the discretion otherwise afforded to high school teachers regarding specific educational content and methods is "naturally subject to limitations."

- Teachers' Conduct as Clear Violations: The Court found that the actions of X2 and X3—such as deviating from the Curriculum Guidelines, not using prescribed textbooks, failing to conduct examinations, and applying uniform grade evaluations—pertained to "pivotal aspects" of educational activity, namely daily classroom instruction in their subjects, student examinations, and academic assessment. Even acknowledging the general professional discretion that teachers possess, the Court concluded that the conduct of X2 and X3 "clearly deviated from that scope and manifestly violated the provisions of the School Education Act and the regulations of the Curriculum Guidelines" that govern daily education. Moreover, the Court characterized the "degree of these acts' violation of laws and regulations (法規違反 - hōki ihan)" by X2 and X3 as "by no means light."

- Discretion of the Disciplinary Authority: The Supreme Court reiterated the established legal principle that the decision whether to impose disciplinary action, and what kind of action to choose, falls within the broad discretion of the disciplinary authority (in this case, the Prefectural Board of Education). This authority is expected to comprehensively consider various factors, including the cause, motive, nature, manner, consequences, and impact of the misconduct, as well as the employee's attitude before and after the conduct, their prior disciplinary record, and the potential effect of the chosen disciplinary measure on other public employees and society. A court reviewing such a disciplinary decision should not substitute its own judgment for that of the disciplinary authority. Instead, a court should only find a disciplinary action illegal if it is "so lacking in social reasonableness as to be a deviation from or an abuse of the scope of discretion." (This refers to a standard set in a 1977 Supreme Court precedent).

- Dismissal Not an Abuse of Discretion in This Case: Applying this standard, the Supreme Court concluded that the dismissals of X2 and X3 were not an abuse of discretion. The Court considered the seriousness and persistence of the violations (e.g., continued non-use of textbooks by X2, significant deviation from curriculum goals in X3's exam questions and teaching content), the teachers' prior disciplinary records (both had received previous disciplinary actions for participating in strikes), and the highly disruptive and chaotic environment that existed at Denshūkan High School at the time, which their actions likely exacerbated. Given all these circumstances, the decision to dismiss them could not be deemed "so lacking in social reasonableness" as to be an abuse of power.

The Legal Status of the Curriculum Guidelines

A crucial underlying issue in this case, and in many educational disputes in Japan, is the legal status and binding force of the Curriculum Guidelines.

- Historically, the earliest post-WWII versions of the Guidelines (1947, 1951) were explicitly labeled as "draft proposals" (試案 - shian) and described as "manuals" for teachers. However, from the mid-1950s, the "draft proposal" designation was dropped, and the Guidelines began to be issued as official Ministry of Education Notifications (告示 - kokuji). Following this change, the Ministry started to assert that the Guidelines possessed legally binding force.

- The dominant academic view, particularly the "Broad Framework Standards Theory" (大綱的基準説 - taikōteki kijun setsu), historically argued against the full legal binding force of the detailed content within the Guidelines. This theory suggested that only broad structural elements (like subjects to be taught or standard class hours) were legally binding, and that attempts by the state to enforce detailed content prescriptions could amount to "improper control" (不当な支配 - futō na shihai) over education, which was prohibited by Article 10 of the (now former) Fundamental Law of Education.

- A major Supreme Court ruling in a 1976 textbook certification case (known as the Gakuryoku Test or Gakute case, a criminal matter) addressed the Guidelines. It found that, as a whole, they served as "broad framework standards" and were legally necessary and reasonable for maintaining educational quality and opportunity, thus not constituting "improper control." However, the Gakute judgment did not explicitly state that the Guidelines were "laws/regulations" (hōki) in the strict sense or that all their detailed provisions were directly legally binding on individual teachers in their daily practice. This ambiguity led to continued debate and differing interpretations in lower court decisions.

- The present Supreme Court judgment concerning X2 and X3 (and its companion judgment regarding X1 issued the same day) took a more definitive step. The judgment for X1, on which this judgment implicitly relies, affirmed a lower court finding that the Curriculum Guidelines, having been established by Ministry Notification based on statutory delegation from the School Education Act and its Enforcement Regulations, "possess the character of laws/regulations (法規としての性質を有する - hōki to shite no seishitsu o yūsuru)." By describing the teachers' actions as "violations of laws and regulations" and specifically "manifestly violating... the regulations of the Curriculum Guidelines," this 1990 Supreme Court decision effectively endorsed the view that the Curriculum Guidelines have a legally regulatory and binding character, a point the Gakute judgment had been more circumspect about.

Implications and Nuances from Legal Commentary

Legal commentary on this and related judgments offers further important context:

- The mere fact that the Curriculum Guidelines are issued in the form of a "Notification" (告示 - kokuji) does not automatically mean every aspect of them has the same legally binding force as a statute or a formal cabinet order. Some Notifications are merely administrative rules or guidelines without direct, independent binding legal effect on citizens or all public officials in the same way as a "law/regulation" (hōki).

- Even among Notifications that are considered legally binding, distinctions can be made. For instance, some Notifications set out formal requirements for administrative dispositions (e.g., standards for textbook approval, where the Guidelines play a direct role), while others (like the Guidelines in this disciplinary context) are referred to as standards against which conduct is judged.

- The 1990 Supreme Court judgments did not fully resolve all interpretative debates surrounding the precise scope and nature of the Curriculum Guidelines' legal binding force. The judgments themselves did not provide an exhaustive explanation for why or to what extent all parts of the Guidelines possess this regulatory character. Consequently, some lower courts, even after these 1990 rulings, continued to express reservations about the binding force of highly detailed or specific elements within the Guidelines that go beyond broad educational frameworks.

- It's also noted that the Curriculum Guidelines themselves have evolved significantly since 1970 (the time of the teachers' actions), generally becoming more detailed and voluminous. Additionally, Japan's Fundamental Law of Education was substantially revised in 2006, with changes that, among other things, arguably strengthen the role of the national government in education. These developments might influence future judicial interpretations of the legal nature and effect of the current Curriculum Guidelines.

Conclusion

The 1990 Supreme Court decision in the Denshūkan High School teachers' case is a significant ruling in Japanese educational law. It affirmed the legally regulatory character of the National Curriculum Guidelines, treating serious deviations from them by public school teachers as violations of legal duty that can warrant severe disciplinary sanctions, including dismissal. The judgment underscored the broad discretion held by educational authorities in disciplinary matters, limiting judicial intervention to cases where that discretion is clearly abused. While not settling every nuanced debate about the precise legal standing of every detail within the extensive Curriculum Guidelines, the decision strongly signaled that these Guidelines are not mere suggestions but constitute binding standards for public school teachers in the conduct of their core educational duties. The case continues to be a key reference point in discussions about educational standardization, the extent of teachers' professional autonomy, and the legal framework governing public education in Japan.