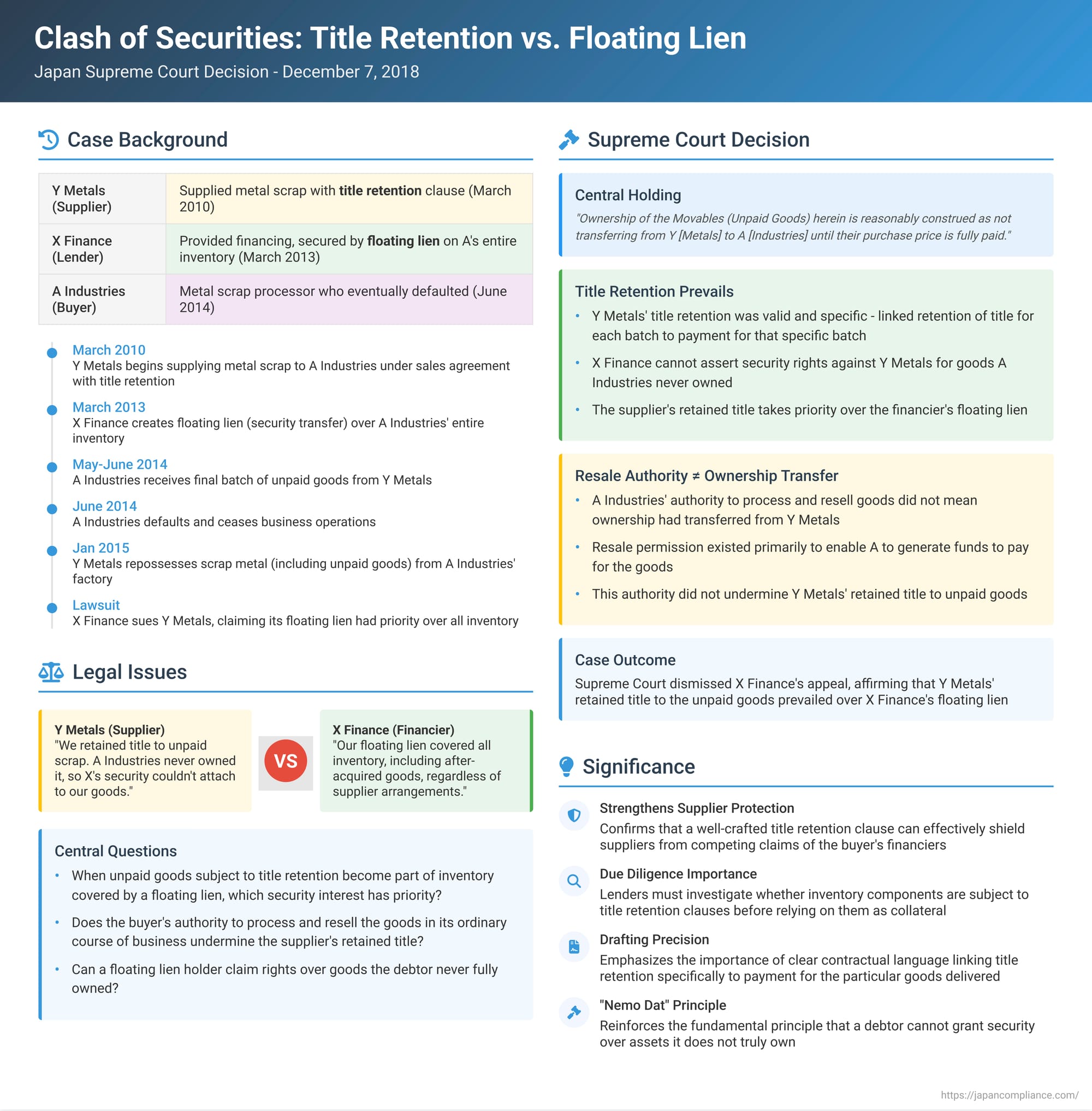

Clash of Securities: Title Retention vs. Floating Lien on Inventory in Japan

Date of Judgment: December 7, 2018

Case Name: Action for Return of Unjust Enrichment, etc.

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

Modern commerce relies heavily on various forms of financing and security. Suppliers often sell goods on credit, sometimes using "title retention" (shoyūken ryūho) clauses where they retain ownership of the goods until full payment is received. Simultaneously, businesses may obtain financing by granting lenders a "security transfer" (jōto tanpo) over their entire inventory, including future acquisitions, creating a "floating lien" over these aggregate movables (shūgō dōsan). A critical conflict arises when goods delivered by a supplier under a title retention agreement become part of an inventory that is already subject to a financier's floating security interest, especially if the business subsequently defaults. Which security interest prevails over goods that the business hasn't yet paid its supplier for? The Supreme Court of Japan provided a significant ruling on this complex priority issue on December 7, 2018.

The Commercial Setting: A Metal Scrap Dealer, a Supplier, and a Financier

The case involved A Industries, a company that processed and sold metal scrap. It had financing and supply relationships with X Finance and Y Metals, respectively.

- Y Metals' Supply with Title Retention: On March 10, 2010, Y Metals entered into an ongoing agreement ("the Sales Agreement") to supply metal scrap to A Industries[cite: 100].

- Under this agreement, A Industries would receive deliveries of scrap from Y Metals.

- A key provision was that ownership of the scrap delivered within each monthly cycle was retained by Y Metals until A Industries fully paid the purchase price for that specific monthly batch[cite: 100]. This is a typical title retention clause.

- Y Metals had given A Industries blanket consent to process and resell the scrap supplied by Y Metals in A Industries' ordinary course of business[cite: 100]. This allowed A Industries to operate its business using the supplied materials.

- X Finance's Security Transfer over Inventory: On March 11, 2013, X Finance entered into an "aggregate movables security transfer agreement" with A Industries[cite: 100].

- This agreement was to secure loan obligations A Industries owed to X Finance[cite: 100].

- The subject matter of this security transfer was all of A Industries' inventory of non-ferrous metal products, raw materials, and work-in-progress that A Industries owned and stored at its factory in Gotemba City and its refining department (the "Specified Locations")[cite: 100].

- The security interest was perfected for existing inventory by "constructive delivery" (sen'yū kaitei) (where A Industries acknowledged holding the inventory for X Finance while retaining physical possession)[cite: 100]. The agreement also stipulated that any after-acquired inventory falling within the definition would automatically become subject to the security transfer upon its entry into the Specified Locations[cite: 100].

- This security transfer was also registered on March 11, 2013, under Japan's Act on Special Provisions for Civil Code Concerning Perfection of Assignment of Movables and Claims (often referred to as the dōsan saiken jōto tokureihō), providing an additional layer of public notice[cite: 100].

- A Industries' Default and Y Metals' Repossession: A Industries eventually ceased its business operations on June 18, 2014[cite: 100]. At that point, it had not paid Y Metals for a batch of metal scrap delivered between May 21 and June 18, 2014 (the "Unpaid Goods")[cite: 100].

- Y Metals, asserting its retained ownership over the scrap it had supplied, obtained a provisional court order allowing it to take delivery of scrap from A Industries' factory[cite: 100].

- In January 2015, Y Metals acted on this order, repossessed a quantity of scrap from the factory, and subsequently sold it to a third party[cite: 100]. The repossessed scrap included some materials for which A Industries had already paid Y Metals ("Paid Goods"), as well as the Unpaid Goods (which the judgment specifically terms "the Movables" for the purpose of its analysis of the dispute with X Finance)[cite: 100].

- X Finance's Lawsuit: X Finance sued Y Metals. X Finance argued that its perfected security transfer over A Industries' entire inventory gave it a priority claim to all the scrap Y Metals had repossessed, including the Unpaid Goods. X Finance alleged that Y Metals' actions constituted a tort (conversion) against its security interest and also resulted in Y Metals being unjustly enriched. X Finance sought damages or the return of unjust enrichment[cite: 100].

The Core Legal Question: Whose Security Interest Prevails over the Unpaid Goods?

The central dispute on appeal to the Supreme Court concerned the Unpaid Goods. The High Court had already ruled in favor of X Finance concerning the Paid Goods, reasoning that once A Industries had paid Y Metals for those goods, ownership had passed to A Industries, and these goods therefore became validly subject to X Finance's pre-existing security transfer over A Industries' inventory. However, for the Unpaid Goods, the High Court held that Y Metals' retained ownership prevailed, meaning A Industries had never acquired ownership of these specific goods, and thus could not have subjected them to X Finance's security transfer. X Finance appealed this part of the decision concerning the Unpaid Goods.

The Supreme Court's Judgment (December 7, 2018): Retained Title Holds Strong (for Unpaid Goods)

The Supreme Court dismissed X Finance's appeal, affirming the High Court's decision that Y Metals' retained ownership over the Unpaid Goods took precedence over X Finance's security transfer interest.

I. Nature and Scope of Y Metals' Title Retention:

The Court carefully analyzed the Sales Agreement between Y Metals and A Industries[cite: 100].

- It found that the title retention clause was specific and linked to payment cycles: ownership of the metal scrap delivered within a particular monthly period was retained by Y Metals only until the purchase price for that specific period's deliveries was fully paid[cite: 100]. The agreement did not intend for ownership of one batch of goods to be retained as security for payment of different, earlier or later, batches of goods[cite: 100].

- The Court characterized such a title retention clause in an ongoing sales contract for movables as a means for the seller to secure payment for goods delivered, operative from the time of delivery until full payment for that specific consignment[cite: 100].

II. Effect of A Industries' Authority to Resell the Scrap:

The Court considered the fact that Y Metals had granted A Industries comprehensive consent to resell the scrap in its ordinary course of business[cite: 100].

- It interpreted this consent as being primarily for the purpose of enabling A Industries to generate the necessary funds to pay Y Metals for the supplied scrap[cite: 100].

- Crucially, the Court stated that this authority to resell did not mean that ownership of the scrap had transferred from Y Metals to A Industries before A Industries had actually paid Y Metals for those specific goods[cite: 100].

III. Conclusion on Ownership of the Unpaid Goods and Priority:

Based on the above, the Supreme Court concluded:

- "Ownership of the Movables (the Unpaid Goods) herein, as stipulated by the [title retention] clause in this case, is reasonably construed as not transferring from Y [Metals] to A [Industries] until their purchase price is fully paid[cite: 100].

- "Therefore, X [Finance] cannot assert the security transfer right herein against Y [Metals] with respect to the Movables herein[cite: 100]."

In essence, because A Industries had not paid Y Metals for the Unpaid Goods, A Industries never acquired ownership of those particular goods. Since A Industries did not own them, it could not effectively include them within the scope of the security transfer it had granted to X Finance. X Finance's security interest (its floating lien on inventory) could only attach to assets that A Industries actually owned or subsequently acquired full ownership of.

Key Takeaways: Title Retention vs. Floating Security Interest on Inventory

This Supreme Court judgment provides critical clarifications on the interplay between two common commercial security devices:

- Specificity and Linkage in Title Retention: The effectiveness of Y Metals' title retention was significantly bolstered by the fact that the Sales Agreement linked the retention of title for each batch of goods specifically to the payment for that same batch. This prevented the title retention from being construed as an overly broad security interest covering unrelated debts, which might have made it more vulnerable to challenge. Sellers using title retention should ensure their clauses clearly define the scope of retention and its connection to specific payment obligations.

- Buyer's Power of Disposition vs. Ownership: A buyer's (A Industries') authority from a title-retaining seller (Y Metals) to process and resell goods in the ordinary course of business is a practical necessity for ongoing commerce. However, this judgment underscores that such a power of disposition does not equate to the buyer acquiring ownership of the goods before making payment, especially for the purpose of granting security interests over those specific unpaid goods to other creditors (like X Finance). The buyer cannot grant a security interest in something it does not yet own.

- "Nemo Dat Quod Non Habet" Principle: The underlying principle is fundamental: one cannot give what one does not have. X Finance's security transfer was granted by A Industries. If A Industries never acquired ownership of the Unpaid Goods from Y Metals, then X Finance's security interest simply could not attach to those specific goods, regardless of how broadly its security agreement was worded concerning "all inventory."

Broader Context: Legal Nature of Title Retention and Perfection

While the Supreme Court focused on the direct ownership question, legal commentary around such cases often delves into the theoretical nature of title retention.

- Is title retention full ownership or a security interest? There are various academic theories. Some view the seller as retaining full, undiluted ownership until final payment (with the buyer having perhaps only a contractual right or an "expectancy" to acquire title). Others see the buyer as acquiring a form of beneficial ownership upon delivery, with the seller retaining a security title akin to a mortgage. This judgment, by stating that ownership "does not transfer" to the buyer until payment, appears to lean towards a strong interpretation of the seller's retained ownership concerning the specific unpaid goods.

- Perfection: X Finance had perfected its security transfer over A Industries' general inventory through both constructive delivery and statutory registration. Y Metals' title retention, by its nature as a reservation of its own ownership, does not require the same kind of "perfection" acts against the buyer (A Industries) to be effective between Y Metals and A Industries. The issue arises when a third party like X Finance claims an interest through A Industries. The Supreme Court's decision indicates that if A Industries never owned the goods, X Finance's perfection acts are futile with respect to those specific goods.

Some legal scholars discuss whether, in certain situations (e.g., if a seller's title retention is unusually broad or secures debts not directly related to the specific goods – lacking "connectedness" or kenrensei), the seller's retained title might itself need to be treated as a security interest requiring some form of perfection to be effective against third-party creditors of the buyer who might otherwise be misled. However, this judgment, emphasizing the specific linkage between the Unpaid Goods and the unpaid price for those goods, did not find Y Metals' title retention to be overreaching in that respect.

The Court also did not need to delve into whether X Finance could have acquired an interest in the Unpaid Goods through "immediate acquisition" (sokuji shutoku), as X Finance was primarily asserting its rights based on the security transfer from A Industries. As a general rule, immediate acquisition is difficult to establish when perfection is by constructive delivery or through the movable assignment registration system, as these typically do not involve the type of direct, good-faith possession by the acquirer that the doctrine of immediate acquisition often requires.

Practical Implications

This judgment has important practical implications for parties involved in inventory financing and supply chains:

- For Financiers Taking Floating Liens (like X Finance): It underscores the importance of conducting due diligence on the debtor's title to its inventory components. A floating lien over "all inventory" may not capture items that are physically present in the debtor's warehouse but for which the debtor has not yet acquired clear ownership from its own suppliers due to effective title retention clauses. Lenders may need to consider the terms under which their borrowers acquire inventory.

- For Suppliers Using Title Retention (like Y Metals): The decision reinforces the strength of a well-defined and specific title retention clause, particularly when it clearly links retention of title for specific goods to the payment for those same goods. It shows that such a clause can effectively protect the supplier's interest in unpaid goods, even if those goods have been intermingled with a larger inventory pool that is subject to a financier's floating security interest. The key is that the buyer cannot grant a security interest over assets it does not truly own.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court of Japan's judgment of December 7, 2018, provides a crucial clarification on the priority between a supplier's specifically retained title over unpaid goods and a financier's broadly defined floating security interest (security transfer) over a buyer's inventory. The Court's decision to uphold the supplier's retained ownership in these circumstances hinges on the fundamental principle that the buyer (the grantor of the inventory security interest) cannot encumber goods to which it has not yet acquired title from its own supplier. This ruling emphasizes the importance of clear contractual drafting in title retention clauses and highlights the limits of a floating lien when faced with a superior, pre-existing reservation of ownership by an unpaid seller.