Clash of Creditors: Assignment for Security over Inventory vs. Seller's Statutory Lien in Japan

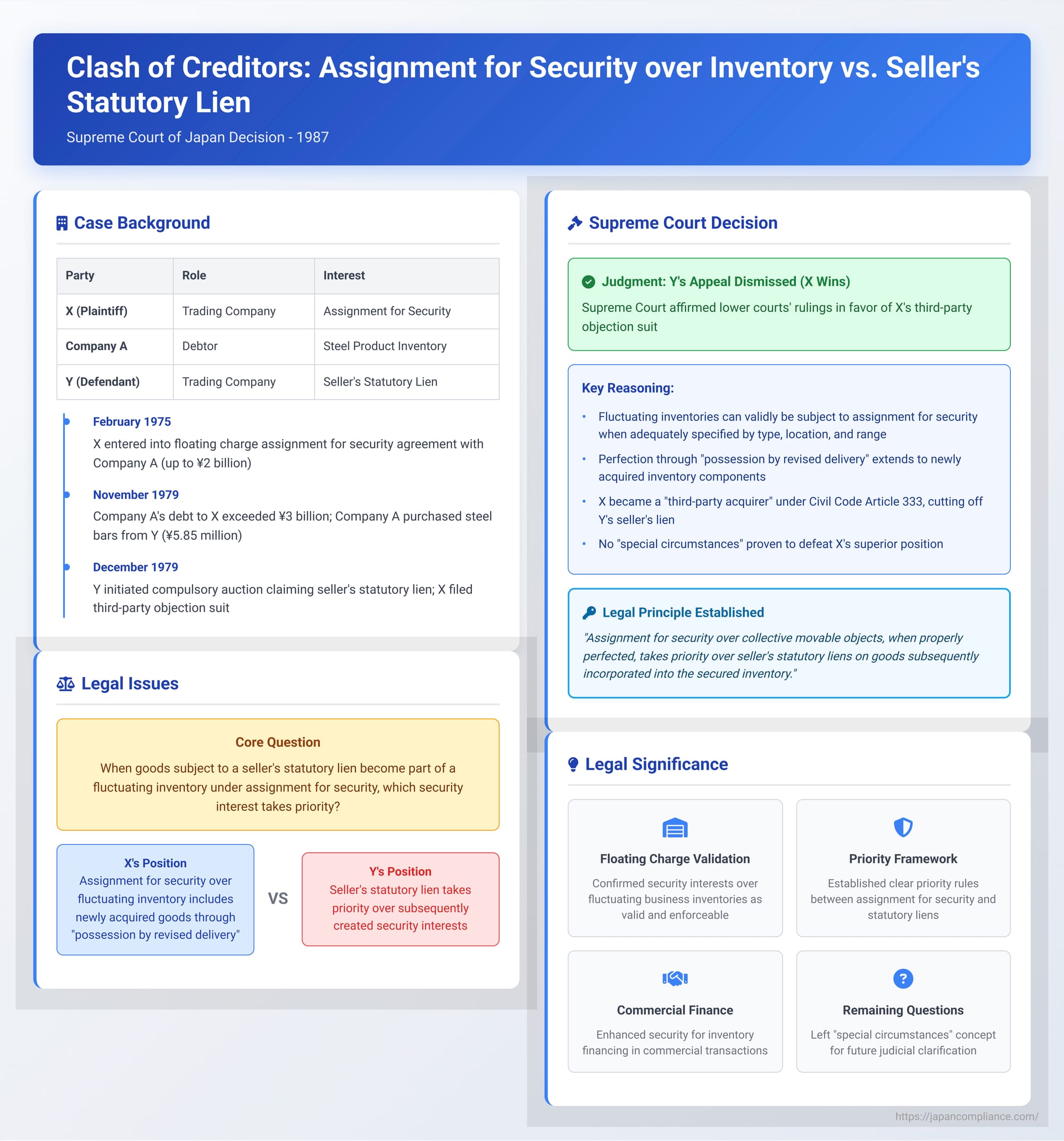

In the complex world of commercial finance and debt recovery, disputes often arise when multiple creditors assert conflicting security interests or claims over the same assets of a debtor. A significant 1987 decision by the Supreme Court of Japan addressed such a conflict, specifically the priority contest between a creditor holding an "assignment for security" (譲渡担保 - jōto tanpo) over a fluctuating inventory of goods and another creditor seeking to enforce a "statutory lien for the sale of movables" (動産売買先取特権 - dōsan baibai sakidori tokken) against specific items that had become part of that inventory. The case was resolved within the framework of a "third-party objection suit" (第三者異議の訴え - daisansha igi no uttae), a crucial remedy for third parties whose property rights are threatened by an execution levied against a debtor.

Background of the Dispute

The plaintiff, X (a major trading company), had entered into a "floating charge assignment for security agreement" (根譲渡担保権設定契約 - ne-jōto tanpoken settei keiyaku) with Company A in February 1975. This comprehensive agreement was designed to secure all present and future debts owed by Company A to X, arising from various transactions such as product sales, promissory note obligations, damages, and advance payments, up to a maximum secured amount of 2 billion yen.

Key terms of this security arrangement stipulated:

- Company A assigned the ownership (both internally between the parties and externally against third parties) of its entire existing inventory of steel products (such as plain bars and deformed bars) located within its specified Warehouses 1 through 4 and the associated premises and yards, to X as security.

- "Delivery" of this inventory to X was deemed to have been completed by the method of "possession by revised delivery" (占有改定 - sen'yū kaitei). This is a form of constructive delivery where the assignor (Company A) continues to physically possess the goods but now holds them on behalf of the assignee (X), for example, as X's agent or bailee. This is a common method for perfecting security interests over movables that need to remain in the debtor's operational control.

- The agreement also stipulated that any similar steel products that Company A manufactured or acquired in the future were, as a general rule, to be brought into these designated storage locations, and these future goods would automatically become part of the collateral under the assignment for security.

X continuously supplied steel products to Company A. By November 30, 1979, Company A's outstanding debt to X for these sales had reached over 3 billion yen, exceeding the 2 billion yen secured limit.

Meanwhile, Company A had also purchased specific deformed steel bars (referred to as the "Goods in Question"), valued at approximately 5.85 million yen, from another major trading company, Y (the defendant). Company A subsequently moved these Goods in Question into one of the warehouse locations already designated under its security agreement with X.

Claiming it held a statutory lien for the sale of movables over these Goods in Question for the unpaid purchase price, Y initiated a compulsory auction of these specific goods in December 1979. This auction was filed under Article 3 of the then-Auction Act (a provision now found in Article 190 of the Civil Execution Act, which allows for the enforcement of certain liens, including a seller's statutory lien over movables, through a simplified auction process).

In response, X filed a third-party objection suit. X argued that, by virtue of the comprehensive assignment for security agreement, it had acquired ownership of the Goods in Question (as they had become part of the specified, fluctuating inventory) and had perfected this ownership interest against third parties through possession by revised delivery. X asserted that its rights were superior to Y's statutory lien and that Y's auction against these goods should therefore be prohibited.

Both the court of first instance and the appellate court ruled in favor of X, upholding X's objection. Y then appealed this decision to the Supreme Court of Japan.

The Supreme Court's Decision

The Supreme Court of Japan dismissed Y's appeal, affirming the judgments of the lower courts that had ruled in favor of X. The Court's reasoning addressed several key legal points concerning assignments for security over fluctuating inventories and their priority:

- Validity of Assignment for Security over Fluctuating Inventory (集合動産譲渡担保 - shūgō dōsan jōto tanpo):

The Court began by reaffirming its established precedent (citing a 1978 Supreme Court decision) that even a fluctuating mass of movables (a "collective movable object") can be validly made the subject of an assignment for security, provided that the scope of the collateral is adequately specified. This specification can be achieved by methods such as defining the type of goods, their location, and their quantitative range. When so specified, such a mass of goods can be treated as a single, collective object for the purpose of creating a security interest. - Perfection and Continuing Effect of the Security Interest:

The Court elaborated on how such a security interest is perfected and how its effect continues despite changes in the inventory's composition. When a security assignment agreement over such a collective object is concluded, and it includes an understanding that the creditor (X) will acquire possession by "possession by revised delivery" whenever the debtor (Company A) acquires possession of goods that become constituent parts of that mass, then the creditor is deemed to have perfected their security interest over the entire collective object once the debtor initially possesses existing constituent parts under this arrangement. Critically, the Court held that the effect of this initial perfection continues to apply to the collective object as a whole, even if its individual constituent parts subsequently change over time (e.g., through sales and new acquisitions), as long as the identity of the collective object as such is maintained (i.e., it remains the specified type of goods in the specified location and within the specified range). This perfection thus extends to newly acquired items that become part of the identified and continuous collective object. - Priority over a Seller's Statutory Lien for Movables:

Applying these principles to the conflict at hand, the Supreme Court concluded that if movables that are subject to a pre-existing seller's statutory lien for their purchase price subsequently become a constituent part of a collective object that is already encumbered by a perfected assignment for security, the holder of the assignment for security (X) can assert their security rights over those specific movables as having been "delivered" to them (constructively, via possession by revised delivery as part of the collective mass).

If the holder of the statutory lien (Y) then attempts to initiate a compulsory auction of these specific movables based on their lien, the holder of the assignment for security (X), in the absence of special circumstances, is to be considered a "third-party acquirer" (第三取得者 - daisan shutokusha) within the meaning of Article 333 of the Civil Code. Article 333 of the Civil Code provides that a statutory lien over movables (like a seller's lien) cannot be exercised against a third party who has acquired the movables once those movables have been delivered to that third-party acquirer.

Therefore, X, as such a third-party acquirer through the perfected assignment for security, could successfully bring a third-party objection suit to demand that Y's auction be prohibited. - Application to the Specific Facts:

The Supreme Court found that:- The agreement between X and Company A validly created an assignment for security over the fluctuating inventory of specified steel products within the clearly designated warehouse locations.

- X had perfected this security interest through possession by revised delivery when Company A initially held possession of the inventory components under the agreement.

- The Goods in Question, sold by Y to Company A, were subsequently brought into the designated warehouse and became part of this secured fluctuating inventory. The overall inventory maintained its identity as the specified collective object.

- Consequently, X's perfected security interest extended to these Goods in Question.

- Given the substantial amount of X's secured claim (over 3 billion yen, far exceeding the value of the Goods in Question, which was approximately 5.85 million yen) and the fact that Y had not alleged or proven any "special circumstances" that might alter this priority, X was entitled to be treated as a third-party acquirer to whom "delivery" (constructive delivery as part of the collective inventory) had been made.

- Therefore, X had the right to prevent Y's auction based on Y's subordinate statutory lien. The High Court's judgment in favor of X was thus correct.

Significance and Analysis of the Decision

This 1987 Supreme Court decision is of considerable importance in Japanese commercial and execution law. It solidified the legal framework for using fluctuating inventories as collateral through the mechanism of assignment for security and clarified its priority over sellers' statutory liens under specific conditions.

- The Nature of a Third-Party Objection Suit:

This lawsuit, provided for in Article 38 of the Civil Execution Act, is a crucial remedy for a third party who claims ownership or other rights that would prevent the sale or delivery of property that has been targeted for compulsory execution against a judgment debtor. The execution agency (e.g., a court bailiff) typically initiates execution based on apparent circumstances, such as the debtor's possession of movables. If these appearances do not reflect the true substantive rights, the third party whose rights are infringed can sue the executing creditor to have the execution against that specific property disallowed. - Why Typical Secured Creditors Often Cannot Use This Suit:

The PDF commentary provides context by explaining that holders of ordinary statutory security interests, such as mortgagees or pledgees, generally cannot use a third-party objection suit to stop execution by a general creditor against the collateral. Their rights are usually protected in other ways:- If their security interest "survives" the execution sale (e.g., certain mortgages under a "take-over principle" where the buyer takes the property subject to the mortgage), their right is not impaired by the sale itself.

- If their security interest is "extinguished" by the execution sale (e.g., most liens, pledges, and some mortgages under an "elimination principle"), they are typically protected by a right to receive preferential payment from the proceeds of the sale. The execution system has mechanisms to ensure this, such as requiring a minimum sale price that covers their claim or by direct distribution priority.

- Assignment for Security (Jōto Tanpo) – A Hybrid Character:

Jōto tanpo is a non-statutory security device extensively developed through case law in Japan. It is structured as a transfer of legal ownership of the collateral to the creditor for security purposes. For movable property, this "transfer of ownership" is perfected against third parties by "delivery." "Possession by revised delivery" (sen'yū kaitei) is commonly used, allowing the debtor to retain physical possession and use of the goods while legally holding them on behalf of the creditor-assignee.

While jōto tanpo takes the outward form of an ownership transfer, the prevailing modern legal understanding in Japan, as noted in the PDF commentary, is to emphasize its functional reality as a security interest. Consequently, there is a strong trend in case law and academic theory to treat jōto tanpo as analogous to statutory security rights wherever possible, especially in its effects and priorities. - The Evolving Treatment of Jōto Tanpo Holders in Executions by Other Creditors:

The PDF commentary traces the historical evolution of how Japanese courts have treated jōto tanpo holders when general creditors of the debtor attempt to seize the assets assigned for security.- Early 20th-century precedents generally allowed jōto tanpo holders, based on their transferred "ownership," to file third-party objection suits to stop such executions, irrespective of the value of the collateral relative to the secured debt.

- However, particularly after World War II, and influenced by Supreme Court decisions that began to treat jōto tanpo more like a security interest in insolvency proceedings (e.g., a 1966 corporate reorganization case) and in the context of preliminarily registered security over real estate (a 1967 case limiting the security holder's assertion to the scope of obtaining priority satisfaction of their claim), the legal landscape shifted. Some lower courts started to restrict the ability of jōto tanpo holders to completely block executions by general creditors, especially if the jōto tanpo holder's claim could be satisfied through priority payment from the auction proceeds. There was a period where third-party objections were often allowed only if the value of the collateral was less than the secured debt (meaning no surplus would be available for the general creditor anyway).

- A significant turning point, or rather a swing back towards strengthening the jōto tanpo holder's position, came with a 1981 Supreme Court decision (Showa 56.12.17). This decision stated that a jōto tanpo holder, "absent special circumstances," can file a third-party objection suit to prevent compulsory execution initiated by a general creditor of the assignor against the secured property. This principle was reiterated in a 1983 Supreme Court case decided under the current Civil Execution Act, which allowed such an objection when "special circumstances" were not proven by the executing general creditor.

- Contribution of the 1987 Decision: The present 1987 Supreme Court decision builds upon this 1981/1983 line of reasoning by:

- Explicitly extending this principle to assignments for security over fluctuating inventories of movables.

- Clarifying that such a third-party objection by the jōto tanpo holder can be successful even against an auction initiated by a creditor holding a seller's statutory lien for movables, provided the goods subject to the lien have been incorporated into the perfected fluctuating security mass. The Court achieved this by classifying the jōto tanpo holder as a "third-party acquirer" to whom "delivery" had occurred for the purposes of Civil Code Article 333, thereby effectively cutting off the statutory lien.

- The Enigma of "Special Circumstances":

A remaining point of discussion, as highlighted in the PDF commentary, is the precise meaning of "special circumstances" that might bar a jōto tanpo holder from successfully bringing a third-party objection suit. The Supreme Court has not yet fully elucidated this. The core of the debate is whether the mere fact that the jōto tanpo holder could receive full satisfaction of their secured debt through priority payment from the proceeds of an auction initiated by another creditor constitutes such "special circumstances."- Arguments for allowing the third-party objection even if full monetary satisfaction is possible often emphasize the jōto tanpo holder's potential interest in acquiring the collateral itself (especially in non-liquidation type security arrangements), their interest in maintaining the ongoing business of the debtor if the collateral is essential ("business continuity interest" or "benefit of continuing the secured transaction"), or their freedom to choose the timing and method of liquidation.

- However, the PDF commentary critically notes that Japanese security and execution law does not generally appear to prioritize these types of interests (control over asset, specific timing of liquidation by secured party) over the right of other creditors to execute, as long as the secured creditor's financial claim is fully protected by priority payment. It also questions the argument that general creditors should simply wait for the jōto tanpo holder to enforce their security and then try to attach any surplus; the law generally allows general creditors to initiate execution even if prior security interests exist (subject to satisfying those prior rights).

- The commentator suggests that if "special circumstances" are found to exist that would negate a full third-party objection (i.e., stop the execution entirely), the judgment should at least confirm the jōto tanpo holder's right to receive preferential payment of their entire secured claim from the proceeds of the other creditor's execution.

- It is generally understood that the burden of proving these "special circumstances" rests on the executing creditor (like Y in this case) who is trying to proceed with their execution despite the jōto tanpo. However, the burden of proving the amount of the debt secured by the jōto tanpo likely falls on the jōto tanpo holder (X).

Conclusion

The 1987 Supreme Court decision significantly bolstered the position of creditors holding an assignment for security over fluctuating inventories in Japan. It confirmed that such security interests, when properly specified and perfected through constructive possession, can take priority over a seller's statutory lien if the goods subject to the lien are subsequently integrated into the secured inventory. By allowing the holder of the assignment for security to file a third-party objection suit and be treated as a "third-party acquirer" under Civil Code Article 333, the Court provided a strong mechanism to protect this form of floating charge against subordinate claims. While the precise scope of "special circumstances" that might limit this right remains a subject for future clarification, this ruling provides crucial guidance for structuring and enforcing security interests over dynamic business assets.