Supreme Court Clarifies Welfare Termination Requires Explicit Written Instructions (Japan, Oct 23 2014)

Japan's Supreme Court (Oct 23 2014): welfare aid may end only for violating a clear written instruction, protecting recipients' rights.

TL;DR

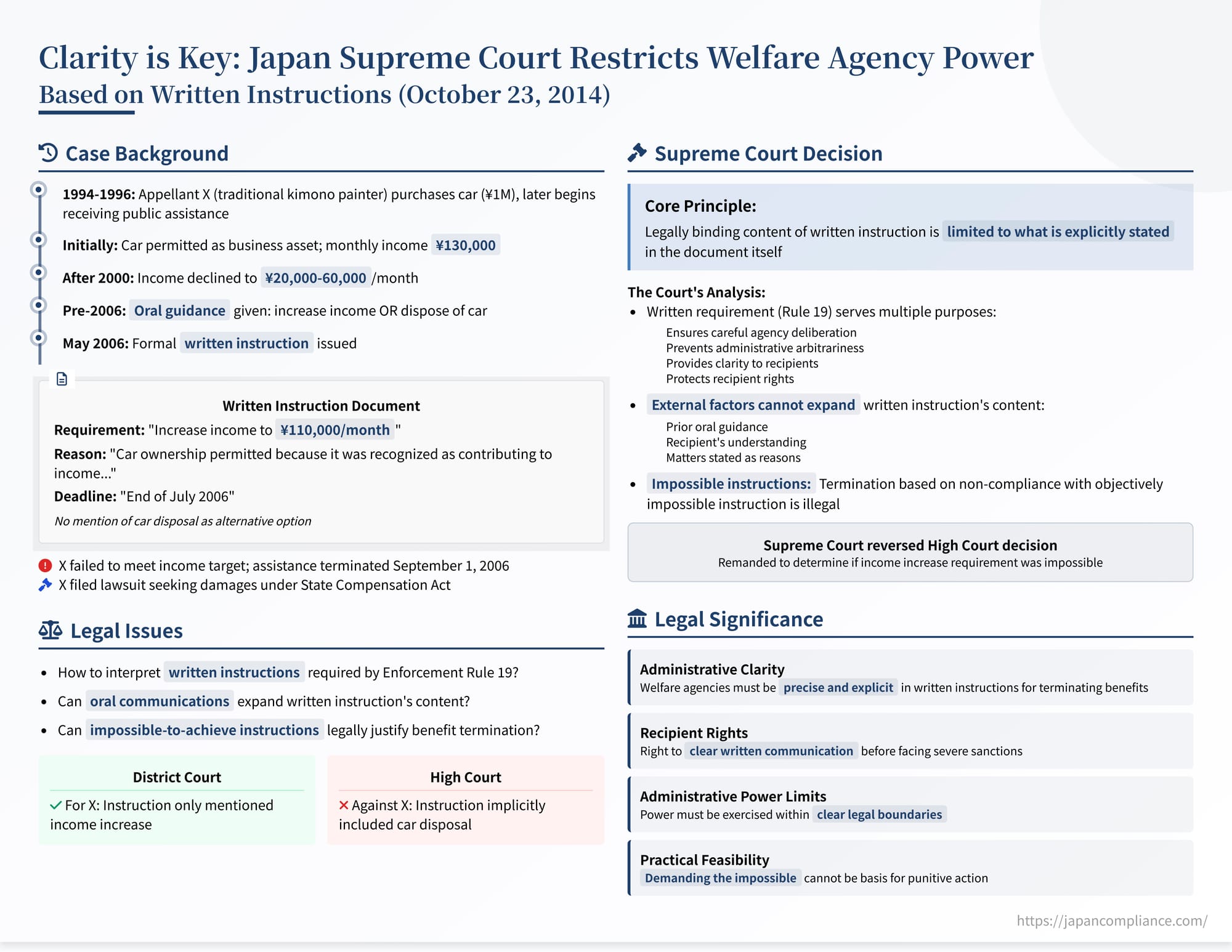

Japan’s Supreme Court ruled on 23 Oct 2014 that welfare benefits can only be terminated when recipients violate the precise content of a written instruction under the Public Assistance Act, rejecting reliance on unwritten context and reinforcing both administrative clarity and recipient rights.

Table of Contents

- Case Background: An Artisan, a Car, and a Written Demand

- The Legal Challenge: An Impossible Instruction?

- The Supreme Court's Analysis: The Primacy of the Written Word

- Remand and Broader Implications

Japan's Public Assistance Act (Seikatsu Hogo Hō) empowers local welfare offices to provide necessary guidance and instructions (shidō mata wa shiji) to recipients to help them maintain their livelihood, improve their situation, or achieve other goals aligned with the Act (Article 27, Paragraph 1). While recipients are generally obligated to follow such guidance (Article 62, Paragraph 1), failure to comply can lead to severe consequences, including the modification, suspension, or even termination of their assistance benefits (Article 62, Paragraph 3). Recognizing the gravity of these consequences, the Act's Enforcement Regulations impose a crucial procedural safeguard: the power to terminate benefits for non-compliance can only be exercised if the preceding guidance or instruction under Article 27(1) was issued in writing (Rule 19).

A Supreme Court of Japan decision dated October 23, 2014, delved into the precise meaning and legal effect of this written requirement. The case examined how strictly the content of a formal written instruction should be interpreted and whether unwritten context or prior discussions could alter a recipient's legal obligations under such an instruction.

Case Background: An Artisan, a Car, and a Written Demand

The appellant, X, had been engaged in Tegaki Yuzen (a traditional craft of hand-painting designs onto kimono fabric) as a home-based piecework business since 1986. In January 1996, X applied for and began receiving public assistance from the welfare office (B Office) administered by the appellee city, Y (Kyoto City).

Crucially, X owned a small car purchased in 1994 for approximately ¥1 million, which was used for the Yuzen business (e.g., transporting materials and finished products). When initially approving X's assistance, the welfare office director (A, the "disposing administrative agency") explicitly permitted X to retain the car as a necessary business asset.

At the start of assistance in January 1996, X's net monthly income from the business was around ¥130,000. However, from the year 2000 onwards, X's income declined significantly, generally ranging between ¥20,000 and ¥60,000 per month. This substantial drop in income raised concerns at the welfare office about the continued justification for retaining the car, as its contribution to X's earnings appeared diminished.

According to the High Court's findings (later overturned by the Supreme Court but relevant for context), the welfare office had repeatedly provided oral guidance to X, suggesting two alternative paths: either significantly increase income from the Yuzen business to justify keeping the car, OR dispose of the car. X reportedly understood this oral guidance.

In May 2006, the situation escalated. The welfare office director (A) issued a formal written instruction to X pursuant to Article 27(1) of the Act. This document (the "Instruction Document") explicitly stated:

- Content of Instruction: "Please increase the income from your Yuzen work to ¥110,000 per month (excluding necessary expenses)."

- Reason for Instruction: "Ownership of the automobile has been permitted since February 2006 because it was recognized as contributing significantly to the household's income increase, but although three months have passed, the objective has not been achieved."

- Compliance Deadline: "End of July 2006."

The document also warned that failure to comply could result in modification, suspension, or termination of assistance.

Notably, the written instruction made no mention of disposing of the car as an alternative means of compliance.

X failed to increase income to the specified level by the deadline. On September 1, 2006, the welfare office director (A) issued a formal decision terminating X's public assistance (the "Termination Decision"), citing "non-compliance with guidance/instruction" as the reason.

The Legal Challenge: An Impossible Instruction?

X subsequently filed a lawsuit against the city (Y), seeking damages under the State Compensation Act. X argued that the Termination Decision was illegal because the underlying written Instruction – demanding an increase in monthly net income to ¥110,000 – was objectively impossible to achieve given the nature of the Yuzen business and prevailing economic conditions.

The legal journey saw conflicting interpretations:

- District Court (Kyoto): The trial court found in favor of X. It reasoned that Enforcement Rule 19 requires the instruction forming the basis of termination to be in writing. Since the Instruction Document only mentioned increasing income, the termination could not legally be based on X's failure to dispose of the car (an option discussed orally but absent from the formal written demand). The court focused on the literal content of the written instruction.

- High Court (Osaka): The appellate court reversed the trial court's decision. It held that the written Instruction Document should be interpreted in light of the preceding oral guidance and the stated reason, which referenced the car's permitted ownership. The High Court concluded that the instruction implicitly included the option to dispose of the car. Since X could have complied by selling the car, the High Court reasoned, the instruction (viewed holistically) was not impossible to fulfill. Therefore, the Termination Decision was deemed lawful.

X appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Analysis: The Primacy of the Written Word

The Supreme Court sided with X, overturning the High Court's judgment and emphasizing the critical importance of the written requirement in Rule 19.

The Purpose of Written Instructions (Rule 19):

The Court began by analyzing the legislative intent behind requiring instructions under Article 27(1) to be in writing before assistance could be terminated under Article 62(3). It identified several key purposes:

- Ensuring Careful Agency Deliberation: Requiring a written document promotes careful and rational decision-making by the welfare office regarding both the instruction itself and any subsequent termination decision.

- Preventing Arbitrariness: The written format acts as a check against arbitrary or capricious actions by the agency.

- Clarity for the Recipient: It clearly defines what guidance or instruction has been given and what the recipient is expected to do.

- Protecting Recipient Rights: It prevents recipients from facing adverse consequences (like termination) based on instructions they may not have fully understood or even been aware of if communicated only orally or ambiguously.

- Ensuring Effectiveness: While protecting rights, the clarity provided by writing also helps ensure the guidance or instruction can be effectively implemented.

Strict Interpretation of Written Content:

Based on this understanding of Rule 19's purpose, the Supreme Court laid down a clear interpretive rule: The legally binding content of a guidance or instruction issued in writing under Article 27(1) (as required by Rule 19 for termination purposes) is limited to what is explicitly stated within that written document itself.

The Court explicitly rejected the High Court's approach of looking beyond the document's text. It stated that factors such as:

- The history leading up to the instruction,

- The content of prior oral guidance or instructions,

- The recipient's understanding or awareness of those prior discussions,

- Matters stated as the reason for the instruction in the written document,

...cannot be used to interpret the content of the formal written instruction as including requirements not actually written down as part of the instruction itself.

Application to the Case:

Applying this strict interpretation, the Court found:

- The Instruction Document explicitly stated only one requirement: increase income from the Yuzen business to ¥110,000 per month.

- There was no mention anywhere in the document that disposing of the car was part of the instruction or an acceptable alternative for compliance.

- Therefore, the only legally binding instruction under Rule 19 was the requirement to increase income.

- Even though the welfare office had previously discussed selling the car orally, X understood this, and the written reason referenced the car, these factors could not legally incorporate "dispose of the car" into the content of the formal written instruction.

The High Court had erred in law by expanding the scope of the written instruction based on extrinsic context.

Remand and Broader Implications

Having established that the instruction solely concerned increasing income, the Supreme Court then addressed the legality of the Termination Decision itself. It affirmed a crucial principle: If guidance or instruction issued under Article 27(1) is objectively impossible or extremely difficult for the recipient to achieve, then terminating assistance under Article 62(3) based on non-compliance with that instruction is illegal.

Since the High Court had wrongly considered the "sell the car" option, it had not properly assessed the feasibility of the actual written instruction (increasing income to ¥110,000/month). Therefore, the Supreme Court reversed the High Court's decision and remanded the case back to the Osaka High Court for further proceedings.

The High Court was directed to determine:

- Whether the instruction, correctly interpreted as requiring only the income increase, was objectively impossible or extremely difficult for X to fulfill by the deadline.

- If it was impossible or extremely difficult, then the Termination Decision based on non-compliance with that instruction would be illegal.

- If the Termination Decision is found illegal, whether this illegality also rises to the level required for state compensation liability under the State Compensation Act.

(On remand, the Osaka High Court subsequently found that the income increase requirement was indeed extremely difficult to achieve and ruled the Termination Decision illegal.)

Significance of the Ruling:

This Supreme Court decision carries significant weight. It strongly reinforces the procedural safeguards intended by the requirement for written instructions in the context of potential public assistance termination. Key takeaways include:

- Administrative Clarity: Welfare agencies must be precise and explicit in their written instructions if those instructions are to form the basis for terminating benefits. Ambiguity or reliance on unwritten understandings is not permissible.

- Recipient Rights: Recipients have the right to know exactly what is required of them through clear, written communication before facing the severe sanction of termination. They cannot be penalized for failing to comply with unwritten demands or interpretations.

- Limits on Agency Power: The ruling underscores that administrative power, even when aimed at promoting self-sufficiency, must be exercised within clear legal and procedural boundaries.

- Feasibility Matters: The court explicitly recognized that instructions must be achievable. Demanding the impossible cannot be a legitimate basis for punitive action.

The judgment highlights the importance of careful documentation and clear communication in administrative actions that profoundly affect individuals' lives. It serves as a reminder that procedural rules, like the written requirement in Rule 19, are not mere formalities but essential components of fairness and due process, particularly for vulnerable populations interacting with state agencies. While broader questions about procedural rights (such as the extent of hearing rights before termination) remain debated in the context of the Public Assistance Act, this decision firmly established the non-negotiable requirement for clarity and limitation in formal written instructions.

- When a Lie Becomes a Crime: Japan's Landmark Case on Lying for an Arrested Friend

- The Scapegoat Gambit: A Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Aiding an Arrested Criminal's Escape

- Memory vs. Truth: How Japan's High Court Defined Perjury Over a Century Ago

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare – Overview of Public Assistance System