Claiming Every Last Yen: Supreme Court on Extending Default Interest in Japanese Debt Distribution Proceedings – A 2009 Case

Date of Judgment: July 14, 2009

Case Name: Distribution Objection Case

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

Case Number: 2008 (Ju) No. 1134

Introduction

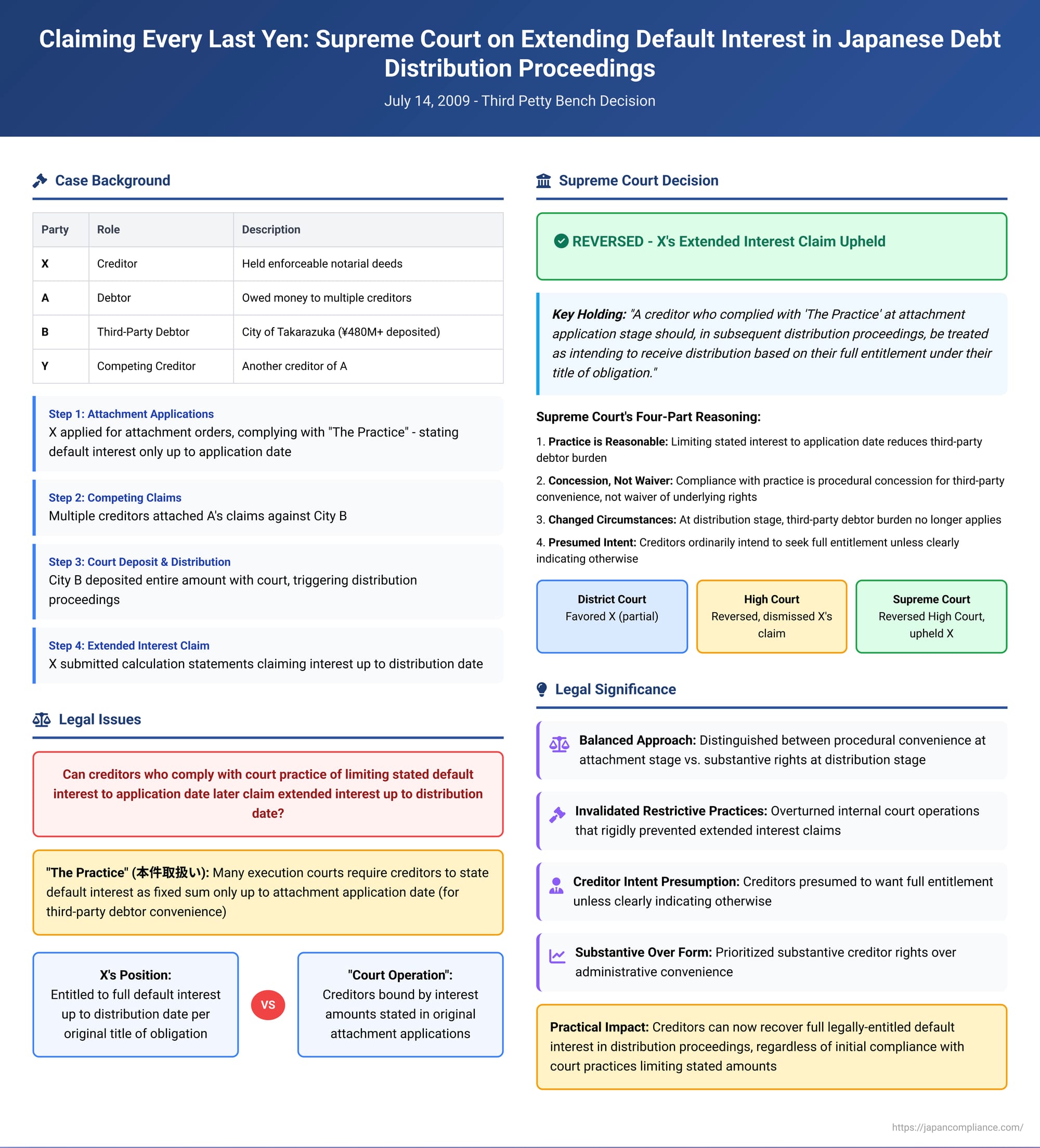

When a creditor enforces a monetary claim that includes ongoing default interest (damages for late payment), a practical question often arises during the attachment process: how much default interest should be specified in the initial court application? Many Japanese execution courts have, for practical reasons, adopted a common practice of requiring creditors to state default interest only up to the date of their application for an attachment order, even if their underlying enforceable title (like a judgment or notarial deed) entitles them to such interest until the principal is fully paid.

This practice simplifies matters for the third-party debtor (e.g., a bank holding the debtor's funds), who then knows a fixed amount being claimed. However, what happens if, due to competing claims from multiple creditors, the third-party debtor deposits the entire attached sum with the court, triggering formal distribution proceedings? Can the initial creditor then "update" their claim to include the default interest that has accrued since their original application date up to the actual distribution date? Or are they bound by the amount stated in their initial attachment application? This was the central issue tackled by the Japanese Supreme Court in a significant judgment on July 14, 2009.

The Facts: An Enforceable Title, a Court Practice, and a Fight for Full Interest

The case involved the following key parties and sequence of events:

- X (Plaintiff/Appellant): The creditor seeking to recover its debt.

- A (Debtor): The individual or entity owing money to X and other creditors.

- B (Third-Party Debtor): The City of Takarazuka, which owed a sum of money (a damages claim) to A.

- Y (Defendant/Appellee): Another creditor of A, competing with X for the funds held by B.

The procedural journey:

- X's Enforceable Titles and Attachment Applications: X held several enforceable notarial deeds against A. These deeds entitled X to claim principal amounts plus default interest calculated until the principal was fully paid. X applied to the Osaka District Court, Sakai Branch, for attachment orders against A's damages claim owed by City B.

- Compliance with "The Practice": The Sakai Branch, like many execution courts, followed a common procedure ("the Practice" - 本件取扱い, honken toriatsukai). This Practice required attaching creditors, in their applications for attachment orders, to specify the amount of default interest as a fixed sum calculated only up to the date of the application. X complied with this Practice in its various attachment applications, stating default interest only up to each respective application date.

- Competing Attachments and Deposit by Third-Party Debtor: Several creditors, including X and Y, had competing attachment orders against A's claim on City B. Faced with these multiple claims, City B deposited the entire amount it owed to A (over JPY 480 million) with the Legal Affairs Bureau on behalf of the court, as permitted under Article 156(2) of the Civil Execution Act. This deposit initiated formal distribution proceedings (配当手続, haitō tetsuzuki) to divide the funds among the eligible creditors.

- X's Calculation Statement for Extended Interest: In the ensuing distribution proceedings, X submitted "calculation statements" (計算書, keisansho) to the Sakai Branch. In these statements, X claimed default interest that had accrued after its initial application dates, right up to the designated distribution date (配当期日, haitō kijitsu).

- The Court Clerk's "Court Operation": However, the Sakai Branch had an internal administrative policy or operational rule ("the Court Operation" - 本件運用, honken un'yō). According to this Operation, even if a creditor who had initially complied with "the Practice" (by limiting default interest to the application date in the attachment order) later submitted a calculation statement claiming further accrued default interest up to the distribution date, the court clerk would not include this additional interest when calculating that creditor's share of the distributable funds. Consequently, the court clerk prepared a distribution table that limited X's default interest to the amounts stated in its original attachment applications.

- X's Distribution Objection Lawsuit: X objected to this distribution table and filed a "distribution objection lawsuit" (配当異議の訴え, haitō igi no uttae) against Y and the other competing creditors. X argued it was entitled to a larger share based on the inclusion of default interest up to the distribution date, as per its calculation statements and underlying titles of obligation.

The Lower Courts' Diverging Views

- First Instance Court (Osaka District Court, Sakai Branch): Partially ruled in favor of X. It ordered a modification of the distribution table, increasing X's allocated share by recognizing some or all of the additional default interest claimed.

- High Court (Osaka High Court): Y appealed this decision. The High Court reversed the first instance judgment and dismissed X's claim entirely. It gave weight to the fact that "the Court Operation" (disallowing later extension of default interest) was an established practice. The High Court reasoned that allowing X's claim for extended interest would create unfairness towards other creditors who had also complied with "the Practice" but might not have submitted similarly extended calculation statements.

X then obtained leave to appeal to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Clarification: Creditors Can Claim Full Interest at Distribution

The Supreme Court, in its judgment of July 14, 2009, reversed the High Court's decision (in the part unfavorable to X) and effectively reinstated the first instance court's judgment which had favored X. The Supreme Court's decision provided crucial clarification on the rights of creditors in distribution proceedings.

The Court's reasoning was structured in two main parts:

I. The Reasonableness of "The Practice" at the Attachment Application Stage:

- Consideration for Third-Party Debtors: The Court began by acknowledging that compulsory execution against monetary claims (where a third-party debtor like City B is involved) imposes significant burdens on that third party. They are prohibited from paying their original creditor (A) and are instead obligated to pay the attaching creditor (X) or deposit the funds with the court (Civil Execution Act Arts. 145, 147, 155, 156). Therefore, procedural considerations must take into account the third-party debtor's burden.

- "The Practice" is Reasonable (but not Legally Mandated): The Court found that "the Practice" of requiring creditors to state default interest in their attachment applications as a fixed sum calculated up to the application date, while not based on any specific statutory provision, is reasonable from the perspective of alleviating the third-party debtor's burden. It prevents a situation where the third-party debtor would have to independently calculate ongoing default interest to determine the exact amount they must pay to the attaching creditor.

- Creditor's Concession, Not Waiver: When a creditor, whose title of obligation actually entitles them to default interest until full payment, complies with "the Practice," they are essentially making a concession for the benefit of the third-party debtor's convenience. They are deemed to have accepted this limitation on the stated default interest only to the extent of this consideration for the third-party debtor.

- Underlying Right to Full Interest Remains: The Court emphasized that a creditor with an enforceable title for principal plus default interest until full payment fundamentally has the right to seek an attachment order covering all such interest. Furthermore, if competing attachments lead to distribution proceedings, such a creditor is generally entitled to receive a distribution calculated on the basis of their full claim as per their title of obligation – i.e., including default interest up to the distribution date. This entitlement exists regardless of whether they submit a specific calculation statement for the extended interest (citing Civil Execution Act Arts. 166(2), 85(1), (2)).

II. Creditor's Intent at the Distribution Stage and the Flaw in "The Court Operation":

- Changed Circumstances at Distribution: The Supreme Court then addressed the situation where, due to competing attachments, the third-party debtor deposits the entire attached sum with the court, and formal distribution proceedings commence. In this scenario, the original rationale for "the Practice" – easing the third-party debtor's calculation burden – no longer applies. The third-party debtor has discharged their obligation by depositing the funds, and the task of calculation now falls to the court and the creditors within the distribution process.

- Presumed Intent of the Creditor: Given this change, the Court stated it is reasonable to assume that a creditor who initially complied with "the Practice" ordinarily intends to seek distribution based on the full amount to which their title of obligation entitles them (i.e., including default interest up to the distribution date).

- The Rule for Distribution: Therefore, the Supreme Court laid down the following rule: A creditor who complied with "the Practice" at the attachment application stage should, in subsequent distribution proceedings, be treated as intending to receive a distribution based on their full entitlement under their title of obligation. They are entitled to receive a distribution calculated on default interest accrued up to the distribution date, generally irrespective of whether they explicitly submit a calculation statement detailing this extended interest.

- Exception: This general entitlement to full interest applies unless the creditor has clearly expressed an intention to receive distribution based only on the fixed default interest amount stated in their original attachment application (e.g., by submitting a calculation statement that explicitly limits their claim to that earlier, fixed amount), or if other special circumstances indicating such a limiting intent exist.

- Application to X's Case: In X's case, not only were there no such special circumstances indicating an intent to limit the claim, but X had proactively submitted calculation statements claiming default interest up to the distribution date. This clearly showed X's intention to pursue its full entitlement.

- High Court's Error: Consequently, the High Court's decision to deny X's claim for extended default interest based on the established "Court Operation" was an error of law that disregarded the creditor's underlying rights once the third-party debtor's convenience was no longer a factor.

Dissecting the Rationale and Its Impact

This Supreme Court judgment was significant for several reasons:

- Balancing Third-Party Convenience and Creditor Rights: It artfully balanced the practical need to simplify procedures for third-party debtors at the initial attachment stage with the substantive right of creditors to eventually recover the full amount due to them under their enforceable titles.

- Clarifying the Nature of "The Practice": It validated the common court practice of limiting stated default interest in attachment applications as a reasonable measure for third-party debtor convenience but underscored that this is a procedural concession by the creditor, not a forfeiture of their underlying right to claim full interest later.

- Overturning Restrictive "Court Operations": The decision effectively invalidated internal court operational rules (like "the Court Operation" at the Sakai Branch) that rigidly prevented creditors from claiming their full, legally-entitled default interest at the distribution stage. It prioritized substantive rights over entrenched but legally unsupported administrative convenience.

- Focus on Creditor's Presumed Intent: The Court's emphasis on the creditor's presumed intent to claim their full entitlement at the distribution stage is noteworthy. It shifts the burden: unless the creditor affirmatively indicates otherwise, they are assumed to want everything they are legally due.

- Irrelevance of Submitting (or not submitting) Extended Calculation Statement for Entitlement: A key takeaway is that the fundamental right to have default interest calculated up to the distribution date stems from the original title of obligation, not from the act of submitting a specific updated calculation statement during the distribution process. While submitting such a statement (as X did) clarifies the creditor's intent, its absence does not, by itself, extinguish the right to the full interest. What would extinguish it is a statement limiting the claim.

Academic and Practical Reception:

The decision was generally well-received by legal scholars, who had often criticized the overly restrictive practices of some courts that denied the extension of default interest. It aligned with the academic view that procedural formalities, while important, should not unduly trample on creditors' substantive rights, especially when the original justification for those formalities (third-party debtor burden) has ceased to exist.

The Follow-Up Issue: Appropriation of Payments

While the 2009 Supreme Court judgment clearly established that the amount of claimable default interest could be extended to the distribution date, it did not explicitly address a related, important question: When the distribution is made, can these newly recognized, extended default interest amounts be satisfied before the principal, in accordance with standard civil law rules of appropriation of payments (where payments are typically applied first to expenses, then interest, then principal)?

This became a point of differing practice among courts:

- The Tokyo District Court Civil Execution Center initially took a narrow view, interpreting the 2009 judgment as only affecting the calculation of the claim amount for distribution shares but not allowing the distributed funds to be preferentially applied to this "extended" portion of default interest.

- The Osaka District Court Civil Execution Center, however, reportedly took a more liberal view, allowing such appropriation.

This particular uncertainty was later resolved by another Supreme Court decision on October 10, 2017. That ruling affirmed that collected funds could be appropriated to cover default interest that accrued from the attachment application date up to the date of collection. Following this 2017 decision, the Tokyo practice was revised to align with allowing such appropriation.

Conclusion: Ensuring Full and Fair Recovery for Creditors

The Supreme Court's July 14, 2009, judgment represents a significant step towards ensuring that creditors can recover the full extent of their adjudicated claims, including all legally accrued default interest, within the context of distribution proceedings. It thoughtfully distinguishes between the procedural expediencies appropriate at the initial attachment stage (to protect third-party debtors) and the overriding need for accurate and complete satisfaction of creditors' rights when funds are actually being divided. By clarifying that initial compliance with court practices limiting stated interest does not bar a creditor from claiming their full due at the distribution stage, the Supreme Court reinforced the principle that procedural rules should serve, not subvert, substantive justice.