Choosing Your Court: Japanese Supreme Court Upholds International Jurisdiction Agreement in Shipping Case

Date of Judgment: November 28, 1975

Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

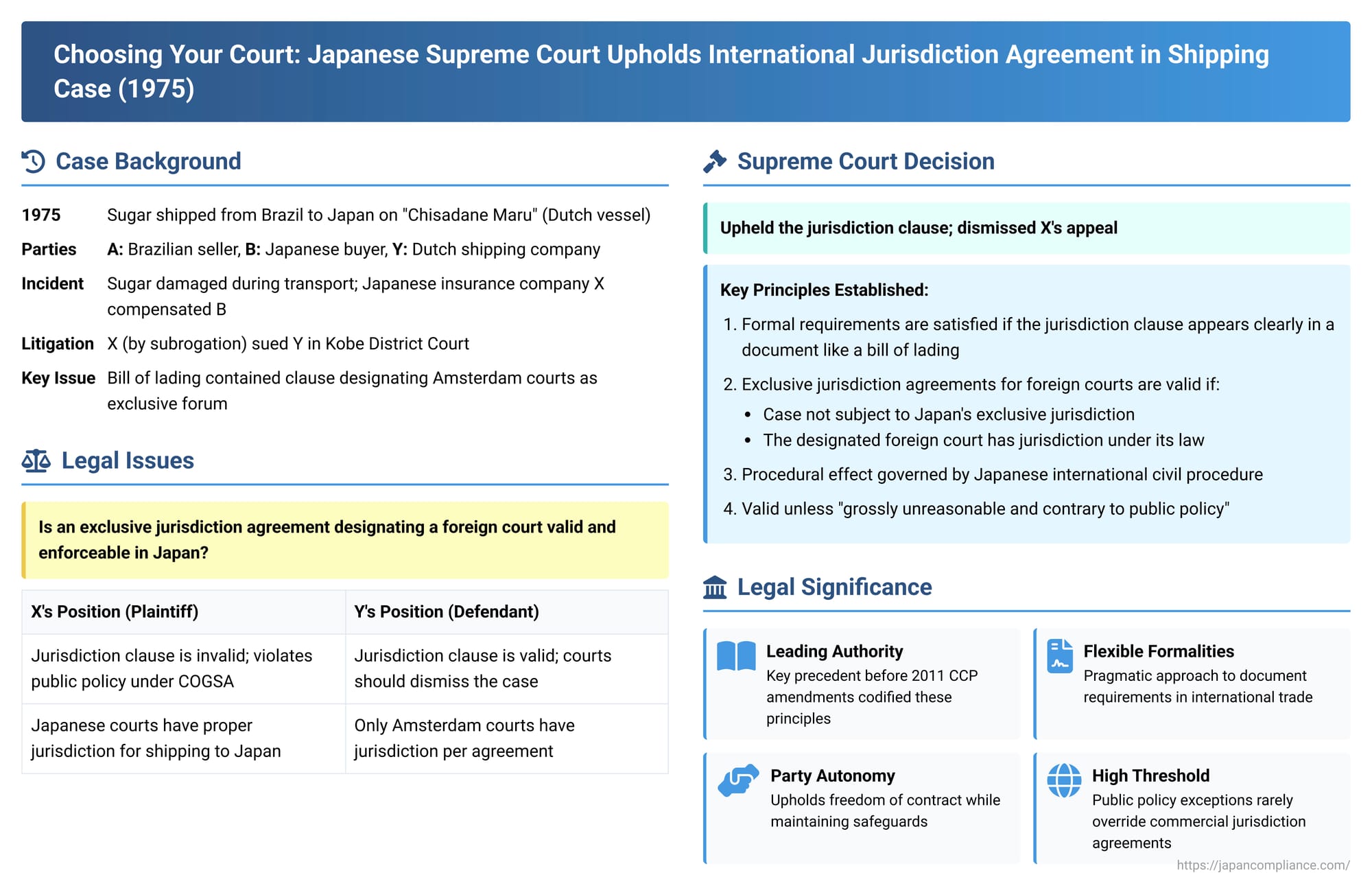

In the realm of international trade and commerce, parties often seek to create predictability by agreeing in advance where potential disputes arising from their contracts will be heard. These "choice-of-court agreements" or "jurisdiction agreements" (合意管轄 - gōi kankatsu) are vital tools for managing legal risk. A landmark decision by the Japanese Supreme Court on November 28, 1975, often referred to as the "Chisadane Maru case," established foundational principles for the validity and effect of such agreements in Japan, particularly those designating a foreign court as the exclusive forum, long before specific statutory rules were codified.

The Factual Background: A Damaged Cargo and a Bill of Lading Clause

The dispute arose from an international shipment of raw sugar:

- A Brazilian company, A, sold raw sugar to a Japanese trading company, B.

- A entrusted the maritime transport of the sugar from Santos, Brazil, to Osaka, Japan, to Y, a Dutch shipping company (Koninklijke Java-China-Paketvaart Lijnen N.V. Amsterdam, operating as Royal Interocean Lines).

- A shipped the sugar on Y's vessel, the "Chisadane Maru." Y issued a bill of lading (船荷証券 - funani shōken) to A, who then delivered it to B.

- The sugar was allegedly damaged during the voyage. X, a Japanese insurance company, compensated B for the loss and, through subrogation, acquired B's claims against Y for damages arising from breach of contract and tort.

- X subsequently filed a lawsuit against Y in the Kobe District Court in Japan.

- The bill of lading, however, contained a jurisdiction clause stating: "All actions under this contract of carriage shall be brought before the Court at Amsterdam and no other Court shall have jurisdiction with regard to any such action unless the Carrier appeals to another jurisdiction or voluntarily submits himself thereto" (the "Jurisdiction Clause").

- Y invoked this clause, arguing that it established Amsterdam as the exclusive forum for disputes and that Japanese courts therefore lacked jurisdiction.

The Kobe District Court and the Osaka High Court both sided with Y, upholding the Jurisdiction Clause and dismissing X's suit in Japan. X then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Core Legal Question: Is the Exclusive Jurisdiction Agreement for Amsterdam Courts Valid and Enforceable in Japan?

The central issue before the Supreme Court was whether the Jurisdiction Clause in the bill of lading, which purported to grant exclusive jurisdiction to the courts in Amsterdam, was valid and effective to oust the jurisdiction of Japanese courts.

The Supreme Court's Key Rulings

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal, affirming the validity of the exclusive jurisdiction agreement. Its reasoning laid down several important principles:

1. Formalities of International Jurisdiction Agreements:

The Court addressed the formal requirements for such agreements. It held that for an international jurisdiction agreement to be valid in terms of form:

- It is sufficient if a court of a specific country is explicitly designated in a document prepared by at least one of the parties (such as a bill of lading issued by the carrier).

- The existence and content of the agreement between the parties must be clear from this documentation.

- It is not necessary that both the offer and acceptance of the jurisdiction agreement be evidenced by a document bearing the signatures of both parties. This pragmatic approach recognized the realities of international shipping, where bills of lading are standard documents issued by carriers and accepted by shippers.

2. Interpretation as an Exclusive Agreement:

The Supreme Court considered whether the Jurisdiction Clause was merely an agreement for an additional possible forum or if it was intended to be exclusive.

- It noted that in this case, both Amsterdam (as Y's head office location) and Japan (where Y had a business office) could potentially have statutory jurisdiction.

- The wording of the clause ("...no other Court shall have jurisdiction...") clearly indicated an intention to retain jurisdiction only in Amsterdam for claims against the carrier and to exclude other courts.

- Therefore, the agreement was properly construed as an exclusive jurisdiction agreement (専属管轄合意 - senzoku kankatsu gōi).

3. General Validity of International Exclusive Jurisdiction Agreements Designating a Foreign Court:

The Court established the general conditions under which an international agreement granting exclusive jurisdiction to a foreign court and ousting Japanese jurisdiction would be considered valid in Japan:

* (a) The case must not be subject to Japan's exclusive domestic jurisdiction. Certain matters, such as those involving title to real estate in Japan, are reserved for Japanese courts alone.

* (b) The designated foreign court must have jurisdiction over the case under its own foreign law. This ensures that the parties are not left without a competent forum.

4. Effect of the Agreement Governed by Forum Law (Japanese International Civil Procedure Law):

The Supreme Court affirmed the High Court's stance that the question of whether such a jurisdiction agreement actually has the effect of excluding Japanese courts' jurisdiction is a procedural matter to be determined by Japan's international civil procedure law (as the law of the forum where the suit was brought). (Academic commentary notes that this pertains to the procedural effect of the agreement, while the contractual formation and validity of the agreement itself might be governed by a separate body of substantive contract law chosen by the parties or by conflict-of-law rules for contracts).

5. Public Policy and Reasonableness Check:

X had argued that the Jurisdiction Clause was contrary to public policy (公序法 - kōjo hō), particularly the provisions of the International Carriage of Goods by Sea Act (COGSA) aimed at preventing carriers from unfairly limiting their liability. The Supreme Court addressed this by stating:

- An international exclusive jurisdiction agreement that designates the courts of the defendant's general forum (in this case, Y's head office in Amsterdam) as the exclusive court of first instance is, in principle, valid.

- This aligns with the widely accepted principle of "actor sequitur forum rei" (the plaintiff follows the forum of the defendant).

- It also recognizes that for an international shipping carrier, seeking to limit jurisdiction for disputes arising from its widespread international transactions to the courts of a specific country (often its principal place of business) is a legitimate and protectable business policy.

- Such an agreement would only be invalidated if it were "grossly unreasonable and contrary to public policy" or if other similar exceptional circumstances existed.

- In this case, the clause designating Amsterdam was not found to be grossly unreasonable or to violate public policy, even considering the points X raised concerning COGSA. The provisions of COGSA are primarily aimed at substantive liability, not necessarily jurisdiction clauses that designate a competent, albeit foreign, court.

Significance and Lasting Principles

The "Chisadane Maru" judgment was a foundational precedent in Japanese law concerning international jurisdiction agreements for many years and its core principles remain influential:

- Leading Authority: It was the sole Supreme Court decision on this topic before Japan's Code of Civil Procedure was significantly amended in 2011 to include detailed provisions on international jurisdiction, including rules for choice-of-court agreements (e.g., Article 3-7 of the current Code of Civil Procedure). The principles from this case are largely consistent with these later statutory rules.

- Flexible Approach to Formalities: The Court's flexible interpretation of the writing requirement for jurisdiction agreements—not strictly requiring signatures from both parties if the agreement's existence and terms are otherwise clear from documents like a bill of lading—is particularly relevant for international trade practices and is reflected in the spirit of current Japanese law (e.g., CCP Art. 3-7(2)).

- Upholding Party Autonomy (with Limits): The decision strongly supports the ability of parties in international contracts to choose their forum, thereby promoting legal certainty and predictability. However, it also maintained safeguards by requiring that the chosen foreign court actually have jurisdiction under its own laws and by subjecting the agreement to a public policy/reasonableness check.

- Public Policy as a High Threshold: The "grossly unreasonable" standard set for invalidating a jurisdiction agreement on public policy grounds indicates that such challenges will rarely succeed, especially when the chosen forum is commercially reasonable (like the defendant's home jurisdiction). While later legislation introduced more specific protections for weaker parties like consumers and employees in jurisdiction agreements (CCP Art. 3-7(5) & (6)), thus reducing the need to rely on the general public policy doctrine in those specific contexts, the underlying principle of a high threshold for invalidating commercial jurisdiction agreements remains.

- Governing Law Considerations: Professor Takahashi's commentary highlights the ongoing academic discussion regarding the law applicable to the jurisdiction agreement itself. While its procedural effect in conferring or ousting jurisdiction is a matter for forum law, the contractual validity, formation, and interpretation of the clause may be subject to the substantive law chosen by the parties for their main contract or determined by other conflict-of-law rules for contracts.

Conclusion

The 1975 "Chisadane Maru" Supreme Court decision was instrumental in shaping Japan's approach to international exclusive jurisdiction agreements. It established a balanced framework that respected party autonomy in choosing a judicial forum for their disputes, while also ensuring that such agreements were clearly evidenced, designated a competent foreign court, and were not grossly unfair or contrary to Japan's fundamental public policy. These principles provided essential guidance for decades and continue to resonate within Japan's current, more codified, legal framework for international civil procedure.