Choking on Mochi: A Japanese Supreme Court Case on 'External Accidents' and Illness Exclusions in Insurance

Date of Judgment: July 6, 2007

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench, Case No. 95 (Ju) of 2007 (Compensation Claim Case)

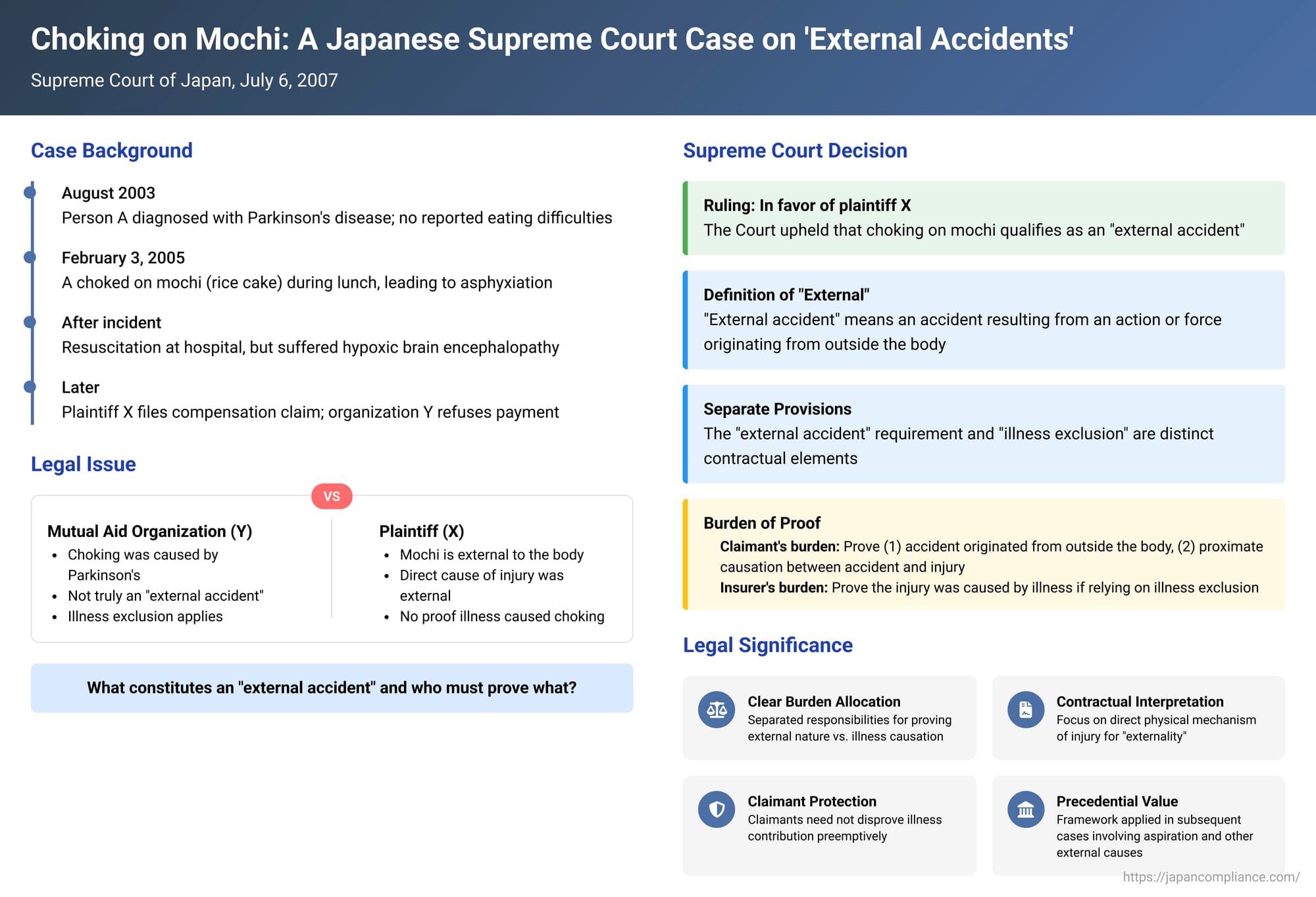

Accident insurance policies, and similar mutual aid agreements, are designed to provide benefits when an insured person suffers an injury due to an accident. A common requirement for coverage is that the injury must result from an "external accident." This term seems straightforward, but its interpretation can become complex, particularly when the insured person has a pre-existing illness that might have contributed to the incident. A notable decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on July 6, 2007, delved into the meaning of "external accident" and clarified who bears the burden of proof for this element, especially in relation to policy clauses that exclude coverage for injuries caused by illness.

The Unfortunate Lunch: Facts of the Case

The plaintiff, X, was a member of Y, a foundational juridical person that provided disaster compensation to its members, a system analogous to accident insurance. The covered person under this mutual aid agreement was an individual named A. According to Y's rules, a "disaster" was defined as an injury sustained due to a "sudden, accidental, and external accident" (急激かつ偶然の外来の事故 - kyūgeki katsu gūzen no gairai no jiko). The rules also contained a crucial exclusion: Y would not pay compensation for injuries "caused by the covered person's illness" (疾病 - shippei).

In August 2003, A was diagnosed with Parkinson's disease. While Parkinson's disease can sometimes lead to swallowing difficulties (dysphagia), A had reportedly experienced no particular problems with eating or drinking, and his doctors had not provided any specific dietary instructions or guidance related to his condition.

The incident in question occurred on February 3, 2005. During lunch, A choked on a piece of mochi (a sticky rice cake). This led to asphyxiation (referred to as "the present accident"). He received immediate resuscitation at a hospital, but the lack of oxygen resulted in hypoxic brain encephalopathy, leaving him with a persistent vegetative state that required constant nursing care.

X, representing A, filed a claim for compensation benefits with Y. However, Y refused to pay. Y's primary argument was that the choking incident was caused by A's pre-existing Parkinson's disease, asserting that potential swallowing difficulties associated with the illness meant the incident was not truly an "external accident" but rather a consequence of an internal, illness-related cause.

The lower courts, including the Tokyo High Court which largely affirmed the Tokyo District Court's findings on the relevant points, ruled in favor of X. The High Court reasoned that "external," in the context of an accident, means the cause of the injury is an action from outside the body, intended to exclude injuries stemming from internal bodily conditions like illness. It held that while the claimant (X) must allege and prove the "externality" of the accident, they do not need to go further and prove the absence of any contributing internal cause. It is sufficient for the claimant to demonstrate, based on the circumstances leading to the injury, that the injury was primarily due to external factors. In A's case, the courts found that the injury (hypoxic encephalopathy) was directly caused by the mochi (an object external to his body) lodging in his trachea—an action from outside the body. The High Court also noted a lack of sufficient evidence to conclude that A's Parkinson's disease directly caused the choking incident. Y then appealed this decision to the Supreme Court, arguing that the High Court's interpretation conflicted with past precedents.

The Legal Definition of "External Accident"

The core of the dispute lay in defining "external accident" and determining how this definition interacts with a separate clause excluding coverage for injuries caused by illness. The central questions were:

- Does "external" refer only to the immediate physical trigger of the injury being from outside the body (like the mochi in this case)?

- Or does it also require the claimant to prove that no internal condition, such as an illness, played a significant role in bringing about the accident?

- How does the burden of proof operate when both an "external accident" requirement and an "illness exclusion" clause are present in the policy?

The Supreme Court's Clarification: Separating "External Accident" from "Illness Exclusion"

The Supreme Court dismissed Y's appeal, upholding the lower courts' decisions in favor of X. The Court provided the following key interpretations:

- Definition of "External Accident": The Court stated that an "external accident," according to the literal wording of Y's rules, means an accident resulting from an action or force originating from outside the covered person's body.

- Illness Exclusion as a Distinct Provision: The Court emphasized that Y's rules contained a separate and distinct provision that explicitly excluded compensation for injuries caused by the covered person's illness. This was not merely part of the definition of "external accident" but a standalone exclusion.

- Burden of Proof Allocation: Given this contractual structure—a definition of "external accident" and a separate illness exclusion—the Supreme Court clarified the burden of proof as follows:

- Claimant's Burden (X): The claimant needs to allege and prove two things: (a) that an accident occurred due to an action from outside the covered person's body, and (b) that there is a proximate causal relationship between that external accident and the injury sustained. Crucially, the claimant does not bear the burden of proving that the injury was not caused by the covered person's pre-existing illness.

- Insurer's Burden (Y): If the insurer wishes to deny the claim on the grounds that the injury was caused by an illness, then the insurer must allege and prove that the illness was indeed the cause, thereby invoking the specific illness exclusion clause.

Application to the Case:

In A's situation, the Supreme Court found it clear that the accident (choking on mochi) was an "accident due to an action from outside A's body". It was also clear that there was a proximate causal relationship between this choking incident and A's resulting injury (hypoxic brain encephalopathy). Therefore, X had met the initial burden. The question of whether A's Parkinson's disease was the legally relevant cause that would trigger the illness exclusion was a matter for Y to prove, which the lower courts had found Y had not sufficiently done.

Unpacking the Significance: Why This Distinction Matters

This Supreme Court decision is significant for its clear demarcation between the requirement of an "external accident" and the operation of an "illness exclusion clause."

- Clarity on "Externality": The ruling interprets "external accident" as focusing on the direct, immediate mechanism of injury. If an external object or force (like a piece of food, a falling object, a collision) is the direct means by which bodily injury occurs, the "external" element is satisfied. This shifts away from a broader interpretation where "external" might have also implied the absence of any internal contributing factors like disease.

- Independent Role of the Illness Exclusion Clause: The decision gives true independent meaning to the illness exclusion clause. It is not merely a confirmatory or cautionary restatement of what is implied by "external accident." Instead, it functions as a specific defense that the insurer can raise, but for which the insurer bears the burden of proof.

- Streamlined Claimant's Burden: This interpretation simplifies the initial evidentiary burden on the claimant. They need to demonstrate the external nature of the event that directly led to the injury, rather than having to preemptively disprove any potential involvement of underlying health conditions.

- Addressing Prior Ambiguity: Previous legal discourse sometimes conflated the concept of an "external" accident with the complete absence of any internal bodily contribution, particularly illness. This often led to debates about whether the claimant needed to prove that an illness was not the indirect cause of the external event. The Supreme Court's decision helps to disentangle these by treating "externality of the accident" and "causation by illness" as separate inquiries with distinct burdens of proof. The commentary notes that the traditional view tended to see "external cause" and "absence of internal (illness) cause" as two sides of the same coin, meaning the claimant had to prove the latter. The alternative view, which the Supreme Court appears to have adopted, focuses the "externality" requirement on the direct cause of the accident itself, leaving the issue of illness as an indirect cause to be handled by the specific illness exclusion clause.

The Broader Context: What "Causes" an Accident?

The Supreme Court's interpretation in this case centers on the direct cause of the physical injury. The piece of mochi directly caused the asphyxiation, which led to the brain injury. Whether an underlying condition (like Parkinson's disease, which can potentially affect swallowing) made A more susceptible to such an accident is a question that falls under the purview of the illness exclusion clause. It is not a factor that negates the "external" nature of the choking event itself. The accident—the physical act of choking on an external substance—remains "external" even if an internal condition might have increased its likelihood. The insurer would then need to prove that the illness was the legally operative cause of the injury to successfully invoke the exclusion.

Legal scholars have pointed out that the Supreme Court, by subtly rephrasing the High Court's language from "cause of injury is external" to "accident due to an action from outside the body," likely intended to underscore that only the direct cause of the accident itself is relevant for determining "externality," not more remote or indirect causes of the ultimate injury.

This approach has been followed in subsequent Supreme Court jurisprudence. For example, a later 2007 decision (Heisei 19.10.19) concerning a personal accident indemnity insurance policy that did not contain a specific illness exclusion clause nevertheless applied a similar interpretation to the "external accident" requirement. Another case in 2013 (Heisei 25.4.16) held that death by asphyxiation due to aspirating vomit also constituted an "external accident," although this particular application has generated some academic debate.

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court's 2007 decision in the "mochi choking" case provides vital guidance for interpreting "external accident" clauses in accident insurance and similar agreements, particularly when a pre-existing illness of the insured is a factor. By clearly separating the definition of an "external accident" from the operation of an "illness exclusion clause," and by allocating the burden of proof accordingly, the Court has established a more structured and arguably fairer framework. Claimants must demonstrate that the immediate cause of their injury was an external event, while insurers bear the responsibility of affirmatively proving that an illness was the legally relevant cause if they wish to rely on an illness-based exclusion. This ruling helps to clarify the pathway for claims and defenses in these often complex and tragic situations.