Child Support and Visitation in Japan: Procedural Reforms and Enforcement Challenges

TL;DR: Japan’s 2024–26 family-law reforms tighten child-support enforcement with statutory liens, salary-garnishment orders and a new automatic-payment system. They also streamline visitation mediation and introduce fines for visitation obstruction. Success will hinge on court capacity and accurate income disclosure.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Strengthening Child-Support Enforcement

- Streamlining Visitation and Contact Procedures

- Remaining Enforcement Challenges

- Comparisons with Other Jurisdictions

- Conclusion

Introduction

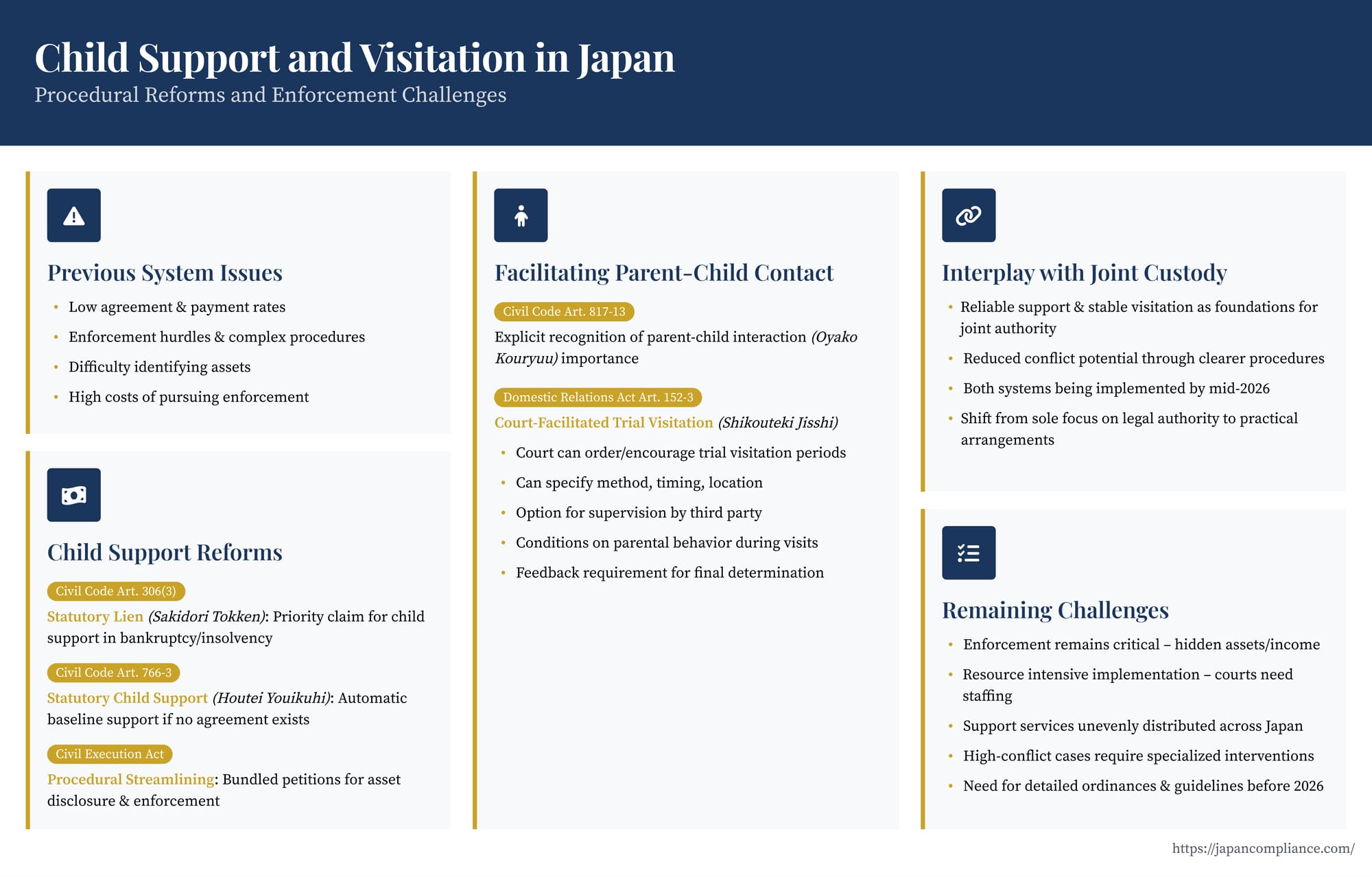

Beyond the headline-grabbing introduction of optional joint parental authority (joint custody), Japan's comprehensive 2024 family law reform (Act No. 33 of 2024, enacted May 2024, effective by mid-2026) includes critical changes aimed directly at improving the practical realities for children after parental separation or divorce. Two key areas addressed are the often-problematic issues of child support (youikuhi 養育費) and parent-child contact, often referred to as visitation (oyako kouryuu 親子交流).

For decades, Japan has faced persistent challenges in these areas. Child support payment rates have remained stubbornly low, contributing significantly to child poverty, particularly in single-mother households. Enforcement of existing support orders was often difficult and costly for custodial parents. Simultaneously, disputes over visitation arrangements were frequent, sometimes leading to the complete cessation of contact between a child and one parent, often amidst high parental conflict.

The 2024 reforms introduce a suite of substantive and procedural changes designed to tackle these issues head-on. They aim to make child support obligations more secure and easier to enforce, while also providing new tools to facilitate appropriate and safe contact between children and both parents. This article examines these crucial reforms related to child support and visitation, explaining the new legal mechanisms and highlighting the ongoing challenges in ensuring their effectiveness.

1. Addressing Chronic Child Support Issues: The Problem

The impetus for reforming child support mechanisms stemmed from widely recognized problems:

- Low Agreement & Payment Rates: A significant percentage of divorcing parents failed to establish formal child support agreements. Even when agreements or court orders existed, compliance rates were notoriously low compared to many other developed nations.

- Enforcement Hurdles: Custodial parents seeking to enforce support obligations faced numerous obstacles:

- Obtaining Orders: Court procedures to establish or modify support could be time-consuming and require legal assistance.

- Identifying Assets: Locating the non-paying parent's income source or assets (bank accounts, employment) for enforcement purposes was often difficult, especially if the parent was self-employed or changed jobs frequently.

- Cost and Burden of Enforcement: Initiating legal enforcement actions (like wage garnishment or seizure of assets) required obtaining a formal legal title (saimu meigi - e.g., court judgment, notarized agreement), paying court fees, and managing the process, which could be burdensome for the custodial parent.

- Financial Hardship: The lack of reliable support payments contributed significantly to financial instability and higher poverty rates among single-parent families, disproportionately affecting children's well-being and opportunities.

2. Key Child Support Reforms: Enhancing Security and Enforcement

The 2024 reform introduces several key measures to strengthen child support:

2.1. Enhancing Priority: The Statutory Lien (Sakidori Tokken)

- The Change (Revised Civil Code Art. 306(3), 308-2): A new general statutory lien (ippan no sakidori tokken) is created for child support obligations. This lien attaches automatically to the debtor parent's general property.

- Scope: The lien applies only up to a "standard necessary amount" for child-rearing expenses. This standard amount will be defined by government ordinance, likely reflecting basic living costs for a child based on age and number of children, rather than the full amount potentially agreed upon or ordered based on parental income.

- Effect: The primary impact occurs in insolvency situations (bankruptcy, civil rehabilitation). The statutory lien gives the child support claim higher priority than general unsecured debts (like credit card debt or general loans), meaning the custodial parent has a better chance of recovering at least the standard support amount from the debtor's limited assets.

- Enforcement: While primarily relevant in insolvency, the existence of the lien might also slightly simplify enforcement outside bankruptcy, potentially allowing direct seizure of assets based on proof of the lien and the underlying obligation (up to the standard amount) without first needing a separate court judgment in some cases, although the practical procedures remain to be fully developed.

2.2. Bridging the Gap: "Statutory Child Support" (Houtei Youikuhi)

- The Change (Revised Civil Code Art. 766-3): This introduces a novel default mechanism. If parents divorce without having made an agreement or obtained a court order regarding child support, the parent primarily caring for the child can automatically claim a legally determined baseline amount of support from the other parent, starting from the month following the divorce.

- Purpose:

- Prevent Gaps: Ensures some level of financial support flows immediately, bridging the potentially lengthy period while parents negotiate or await a court decision on the final support amount.

- Establish Minimum Standard: Provides a safety net based on essential child-rearing costs, ensuring a minimum level of contribution even before a formal agreement.

- Calculation: The specific monthly amount will be calculated according to methods set by government ordinance, considering factors like the standard cost of living for a child and the number of children. It is intended to reflect a minimum necessary amount, likely lower than amounts typically calculated using the standard court tables which consider both parents' incomes.

- Duration: This statutory claim continues monthly until either (a) the parents reach a formal agreement on support, (b) a court issues a support order, or (c) the child reaches adulthood.

- Debtor's Defense: The paying parent is not automatically locked into this amount. They have the right to refuse payment (in whole or part) if they can prove to the court that they lack the financial ability to pay or that payment would cause them "significant hardship" (ichijirushii konkyuu). The court can then modify or waive the statutory amount based on the debtor's circumstances. This provides a crucial fairness check.

2.3. Streamlining Enforcement: Procedural Reforms

Amendments to related procedural laws aim to make enforcing any child support obligation (whether statutory, agreed upon, or court-ordered) less burdensome for the receiving parent:

- Easier Information Access (Revised Domestic Relations Case Procedure Act Art. 152-2): Family Courts are given explicit power to order parties involved in child support determination proceedings to disclose information regarding their income and assets when necessary for calculating or modifying support. Failure to comply without legitimate reason can result in an administrative fine (karyou).

- Bundled Enforcement Petitions (Revised Civil Execution Act Art. 167-17, 193(2)): This significant procedural change allows a creditor holding a valid support title (like a court order or potentially relying on the statutory lien for the standard amount) to file a single petition that combines multiple steps:

- Requesting debtor asset information (either through the formal property disclosure procedure where the debtor lists assets under court supervision, or through requests to third parties like employers for wage information).

- Requesting enforcement action (like wage garnishment or bank account seizure) against assets identified through the disclosure process.

- Aim: To reduce the number of separate court filings and associated costs and delays previously required (i.e., get an order -> separately file for disclosure -> separately file for seizure).

- Limitation: Initially, the bundled third-party information request is limited to obtaining employment/wage information. Obtaining bank account details via third-party request still requires a separate step after initial enforcement attempts are unsuccessful, although future system integration might expand this.

These procedural changes aim to make the often-daunting process of enforcing child support orders more efficient and accessible.

3. Facilitating Parent-Child Contact (Oyako Kouryuu)

The reforms also introduce measures aimed at promoting stable and safe contact between children and non-resident parents, while addressing high-conflict situations.

- The Challenge: Disputes over the frequency, duration, location, and conditions of visitation are common after divorce. Concerns about parental alienation, ensuring the child's safety during visits (especially where DV has been a factor), and managing parental conflict often create barriers to establishing or maintaining contact.

- Codifying Importance of Contact (Revised Civil Code Art. 817-13): While not creating an absolute "right" to visitation, the law now more explicitly recognizes the general principle that considering arrangements for parent-child interaction (kouryuu) is part of determining the child's best interests in custody matters.

- New Procedural Tool: Court-Facilitated Trial Visitation (Shikouteki Jisshi) (Revised Domestic Relations Case Procedure Act Art. 152-3): This is perhaps the most significant procedural innovation regarding visitation.

- Mechanism: During Family Court proceedings related to custody or visitation (either mediation - choutei or adjudication - shinpan), the court now has the explicit authority to order or encourage trial periods of visitation between the child and the non-resident parent.

- Purpose: This tool is intended primarily for investigative purposes by the court. It aims to:

- Gather objective information about the parent-child relationship and the feasibility of contact.

- Assess potential risks and determine appropriate safeguards.

- Help break negotiation impasses by allowing for structured, observed contact.

- Inform the court's final decision on permanent visitation arrangements.

- Court Powers: The court can set specific conditions for the trial visits, including:

- Method (in-person, online).

- Frequency, duration, time, and place.

- Crucially, whether supervision or observation by a third party (e.g., a trained professional from a visitation support center, or a Family Court Investigator - katei saibansho chousakan) is required.

- Imposing conditions on parental behavior during visits (e.g., prohibiting arguments or harmful questioning of the child).

- Feedback: The court can require the parties to report back on how the trial visits went, providing valuable input for the final determination.

- Potential Impact: This mechanism gives courts a more proactive way to manage difficult visitation cases. When used appropriately with necessary safeguards (like supervision in high-conflict or potential risk cases), it could help establish safe and sustainable contact arrangements based on observed reality rather than just parental allegations. However, its effectiveness depends on careful judicial assessment and the availability of qualified supervisors and support services.

4. Interplay with Joint Custody and Remaining Challenges

These reforms to support and visitation are closely linked to the introduction of optional joint custody.

- Foundation for Joint Custody: Reliable child support payments and stable, predictable contact arrangements are often seen as essential prerequisites for making joint parental authority (kyoudou shinken) function effectively and cooperatively. Addressing these practical issues can potentially reduce sources of conflict that might otherwise preclude a joint authority arrangement.

- Enforcement Remains Critical: While the legal tools for support enforcement have been strengthened, their real-world impact depends on consistent application by courts and enforcement agencies. Challenges like debtors hiding assets or income, especially among the self-employed, persist. Further measures, perhaps involving stronger administrative enforcement powers (which were discussed but not adopted this time), might eventually be needed.

- Resource Intensive: Implementing these reforms effectively requires significant investment. Courts need adequate staffing (judges, investigators trained in family dynamics and risk assessment). Accessible and affordable support services – mediation centers, supervised visitation facilities, co-parenting counseling – are crucial for helping families navigate both support issues and the complexities of joint custody or difficult visitation schedules. These resources are currently unevenly distributed across Japan.

- Addressing High Conflict: Legal procedures can only go so far. Addressing the underlying causes of high parental conflict often requires therapeutic or specialized mediation interventions, which need to be integrated with the legal process. Protecting children from exposure to ongoing conflict remains a paramount concern, whether under sole or joint authority.

Conclusion

The 2024 amendments to Japan's family law represent a concerted effort to improve the financial security and emotional well-being of children following parental separation. The introduction of a statutory lien and a baseline statutory claim for child support, coupled with streamlined enforcement procedures, aims to tackle the long-standing problem of unpaid support. Simultaneously, the explicit recognition of parent-child contact's importance and the creation of a court-facilitated trial visitation mechanism provide new tools for managing complex visitation disputes while prioritizing child safety.

These changes, implemented alongside the introduction of optional joint parental authority, signal a significant modernization of Japan's approach to post-divorce family arrangements. The goal is to create a system that is more responsive to children's needs, ensuring they receive necessary financial support and maintain meaningful relationships with both parents whenever safe and appropriate.

However, the ultimate success of these reforms hinges on more than just legislative text. It requires diligent implementation through detailed ordinances and guidelines, substantial investment in judicial resources and family support services across the country, and a continued focus by legal professionals and courts on applying these new tools thoughtfully to serve the best interests of each individual child. As these reforms move towards full implementation by mid-2026, their practical impact on families navigating separation and divorce in Japan will be closely observed.

- Japan Overhauls Family Law: Introducing Joint Custody and Reforming Child Support

- Understanding Post-Divorce Parental Rights in Japan: Key Changes in the New Family Law

- Freedom to Resign vs. Training-Cost Clawbacks in Japan

- Ministry of Justice — Q&A on 2024 Child-Support Enforcement Reform (JP)

https://www.moj.go.jp/MINJI/minji07_00460.html