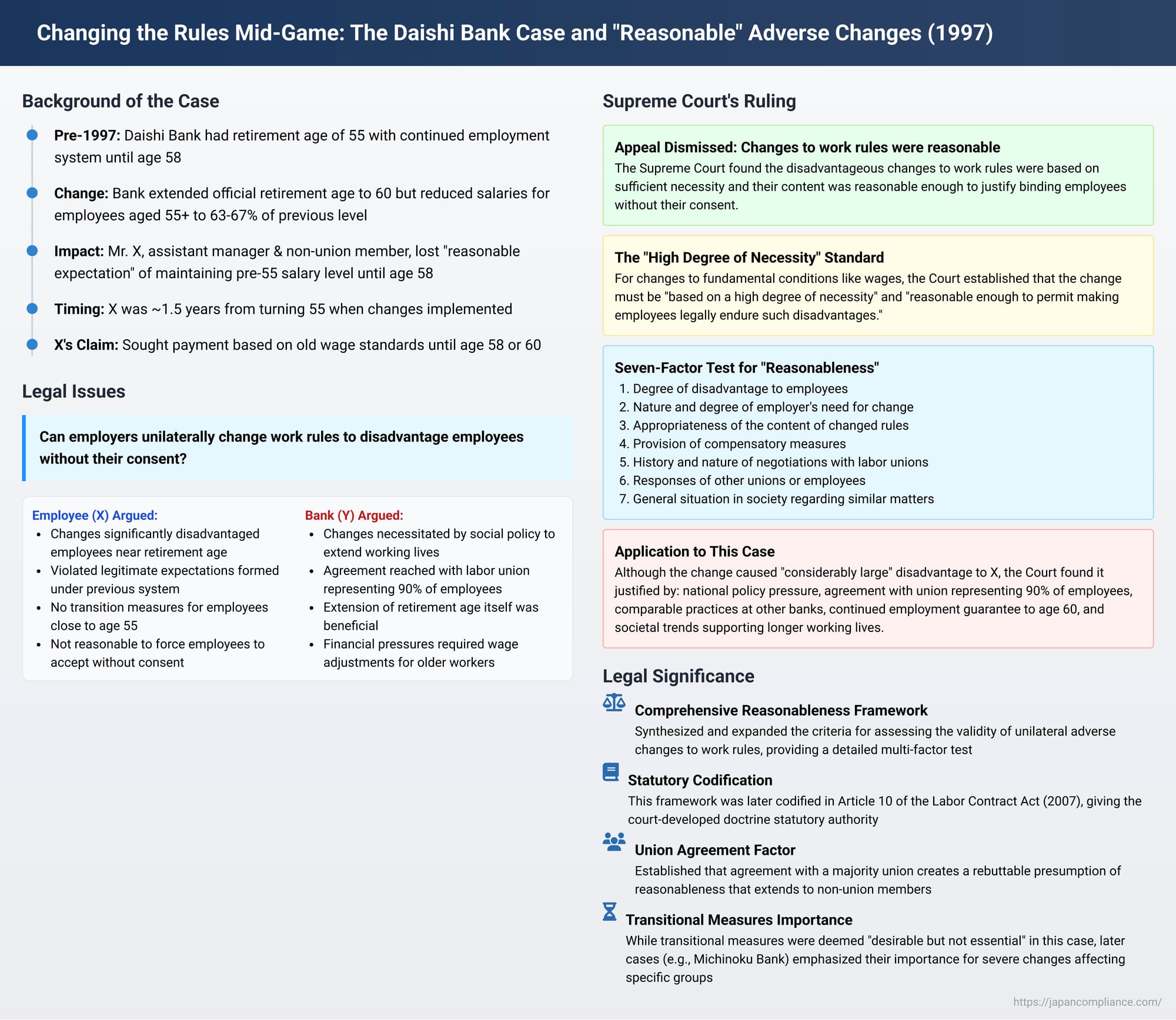

Changing the Rules Mid-Game: Japan's Daishi Bank Case and "Reasonable" Adverse Changes to Work Rules

Altering established employment conditions, particularly those concerning core elements like wages and retirement, presents a significant challenge for employers. While businesses often need to adapt to changing economic landscapes, employees rely on the stability of their terms. In Japan, where work rules (就業規則 - shūgyō kisoku) can be changed by employers, the legal system has developed doctrines to balance these competing interests. The Supreme Court of Japan's decision in the Daishi Bank case on February 28, 1997, is a pivotal judgment that consolidated and extensively elaborated on the criteria for determining when an employer's unilateral, disadvantageous change to work rules can be deemed "reasonable" and thus binding on employees, even those who do not consent.

The Daishi Bank Scenario: Retirement Age Up, Pay Down

The case involved Company Y (The Daishi Bank, Ltd.), a regional bank, and its employee, Mr. X. Y had an official retirement age of 55. However, it also operated a "post-retirement continued employment system," under which healthy male employees could typically continue working until age 58, with their working conditions, including salary, not falling below what they received at age 54. Mr. X, a department assistant manager who was not eligible for union membership under the existing collective agreement, reasonably expected to benefit from this system.

Driven by national policy and societal trends encouraging longer employment, Y decided to extend its official retirement age to 60. Concurrently with this extension, and following negotiations and a formal agreement with its labor union, Y amended its work rules. These amendments introduced significant changes for employees aged 55 and older: their monthly salaries and bonuses were reduced, resulting in their annual income dropping to approximately 63-67% of their earnings at age 54. The practical effect was that employees now had to work nearly to the new retirement age of 60 to accumulate the earnings they had previously expected to achieve by age 58. Mr. X was about a year and a half away from turning 55 when these changes were implemented.

X sued Y, arguing that these adverse changes to the work rules should not apply to him. He sought payment of the wage difference based on the old standards, primarily until he reached age 60, or secondarily, until age 58. The Niigata District Court found the changes unreasonable but dismissed X's claim due to the general binding effect of the collective agreement reached with the union. The Tokyo High Court, however, found the changes reasonable and also dismissed X's appeal. X then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's 1997 Comprehensive Framework for "Reasonableness"

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal, ultimately upholding the validity of the work rule changes. In doing so, it provided a detailed and synthesized framework for assessing the "reasonableness" of unilateral adverse changes to work rules, building upon its earlier jurisprudence, notably the Shuhoku Bus case.

The Court began by reaffirming the established principle: while an employer generally cannot unilaterally deprive employees of vested rights or impose disadvantageous working conditions through the creation or alteration of work rules, an exception exists if the specific rule change is "reasonable." If deemed reasonable, individual employees cannot refuse its application merely because they do not consent.

The Court then elaborated on what constitutes a "reasonable" change. Such a change, considering both its necessity for the employer and its content, must possess a degree of rationality that allows its legal normativity within the specific labor-management relationship to be affirmed, even when factoring in the extent of the disadvantage incurred by the employees.

The "High Degree of Necessity" Standard:

Crucially, the Court introduced a more stringent standard for changes affecting fundamental employment conditions. It stated that for work rule modifications causing substantial disadvantages to important rights and conditions, such as wages and retirement benefits, the change can only take effect if it is "based on a high degree of necessity" and its content is "reasonable enough to permit making employees legally endure such disadvantages".

The Seven Key Factors for Assessing Reasonableness:

The Supreme Court outlined a comprehensive list of factors to be considered in judging this reasonableness:

- The degree of disadvantage incurred by the employees.

- The nature and degree of the employer's need for the change.

- The appropriateness of the content of the changed work rules themselves (e.g., whether it is excessively harsh or an aberration from common practice).

- The provision of compensatory measures and improvements in other related working conditions.

- The history and nature of negotiations with labor unions or other employee representatives.

- The responses and attitudes of other labor unions or employees within the company to the change.

- The general situation in Japanese society regarding similar matters (e.g., prevailing industry practices or responses to societal demands).

Applying the Framework to Daishi Bank's Changes

The Supreme Court meticulously applied this multi-factor test to the Daishi Bank's work rule amendments:

- Nature of X's Interest: The Court acknowledged that while the change didn't extinguish a "vested right" in the strictest legal sense, it did undermine X's "reasonable expectation" of continued earnings under the old post-retirement system. This frustration of expectation was deemed "tantamount to an adverse change in working conditions," thus triggering the "high degree of necessity and reasonable content" standard.

- Disadvantage to Employees (Factor 1): The Court recognized the disadvantage as "considerably large," particularly for employees like X who were close to the former retirement age of 55 and had made future life plans based on the existing system.

- Employer's Necessity (Factor 2): There was a "high degree of necessity" for Y to extend the retirement age to 60, given that it was a national policy objective and a strong societal demand at the time. Y also faced requests from the labor minister, the prefectural governor, and its own union for such an extension. Simultaneously, the bank demonstrated a high degree of necessity to revise the wage structure for employees aged 55 and older to manage the inevitable increase in personnel costs and prevent organizational stagnation due to an aging workforce and limited senior positions. The Court found that modifying only the conditions for those aged 55 and above was an unavoidable approach for the smooth introduction of the extended retirement age.

- Content Appropriateness (Factor 3): The Court noted that the previous terms for those over 55 were not absolute vested rights. The new conditions for employees aged 55-60 under the 60-year retirement system were largely similar to those implemented by many other regional banks undergoing similar changes. Furthermore, Y's wage levels, even after the reduction, remained comparatively high when benchmarked against other banks and general societal wage levels.

- Compensatory Measures/Other Improvements (Factor 4): The extension of the retirement age from 55 to 60 was a clear benefit for female employees (who were generally not part of the old post-retirement scheme) and for male employees whose health might have precluded them from the old scheme. For healthy male employees like X, the guarantee of stable employment for an additional two years (to age 60), even if their health slightly declined, was deemed a "not insignificant" benefit. Additionally, welfare benefits were extended and enhanced, and a special loan system for older employees was introduced. While not direct financial compensation for the wage cut, these measures were related to the new retirement system and helped mitigate the overall negative impact.

- Negotiation History (Factor 5) and Employee Response (Factor 6): The work rule changes were implemented after extensive negotiations and a formal collective agreement with the labor union, which represented approximately 90% of Y's employees (including about 60% of those aged 50 and over). The Court stated that such an agreement with a majority union creates a prima facie inference that the revised work rules are reasonable, reflecting a bargained adjustment of interests between labor and management. This inference generally extends to non-union members like X, unless there are specific circumstances demonstrating that the rules are particularly unreasonable for them. The Court found no such circumstances for X.

- Overall Assessment: Weighing all these factors, the Supreme Court concluded that although the changes caused X considerable disadvantage, especially given his proximity to the old retirement age, they were nonetheless based on a "high degree of necessity" and their content was "reasonable." Therefore, making X legally endure such disadvantages was deemed unavoidable in the broader context.

- Lack of Transitional Measures: The Court acknowledged that providing transitional measures for employees nearing 55 would have been desirable. However, it reasoned that the collective nature of work rules generally calls for a degree of uniformity. Since the change affected "reasonable expectations" rather than divesting strictly defined "vested rights," the absence of specific transitional measures for X did not, in this instance, negate the overall finding of reasonableness. (It is noteworthy that Justice Kawai Shinichi provided a dissenting opinion, arguing that X's interest was very close to a right or legal status and that the lack of transitional measures, without special justification, rendered the change unreasonable for him ).

Key Takeaways and Developments

The Daishi Bank case is a landmark because it meticulously synthesized and articulated the multifaceted test for the reasonableness of adverse work rule changes, a doctrine that had been evolving since the Shuhoku Bus case.

- Codification in the Labor Contract Act (LCA): This judicially developed multi-factor "reasonableness" test was subsequently codified in Article 10 of the Labor Contract Act of 2007. The legislative intent was reportedly to enact the existing case law "without addition or subtraction," meaning the factors listed by Daishi Bank are considered encompassed within the LCA's provisions. For example, "appropriateness of the content of the changed work rules" includes "compensatory measures and improvements in other related working conditions" and "the general situation in Japanese society regarding similar matters," while "status of negotiations with a labor union, etc." includes "responses of other labor unions or other employees".

- The Role of Majority Union Agreement: The Daishi Bank judgment gave significant weight to the agreement with the majority union, suggesting it creates a rebuttable presumption of reasonableness. However, subsequent case law, such as the Michinoku Bank case (Supreme Court, 2000), has shown that such an agreement is not always decisive. In Michinoku Bank, despite majority union consent, a wage system change imposing very severe and concentrated disadvantages on a particular group of older employees without adequate transitional measures was found unreasonable. Thus, union agreement is a strong, but not conclusive, factor, and its weight is assessed within the overall context.

- "Reasonable Expectation" vs. "Vested Right" and Transitional Measures: The Daishi Bank Court's characterization of the affected employee interest as a "reasonable expectation" rather than a "vested right" influenced its assessment of the lack of transitional measures. The dissent, and later the Michinoku Bank ruling (which described similar pre-change wage expectations as having become "part of the working conditions"), highlighted that the nature and severity of the disadvantage are critical in determining the necessity and adequacy of transitional arrangements. If a change disproportionately harms a specific group, especially concerning critical conditions like wages, the lack or inadequacy of measures to cushion the blow becomes a more significant factor in the reasonableness assessment.

Conclusion

The Daishi Bank case provides an extensive and authoritative roadmap for evaluating the "reasonableness" of an employer's unilateral decision to adversely change work rules. It underscores that while employers have a degree of flexibility to adapt to changing circumstances, this power is constrained by the need to demonstrate a high level of necessity and overall fairness, especially when critical employment terms are at stake. The multi-factor test it laid out, now reflected in Article 10 of the Labor Contract Act, ensures a comprehensive judicial review, balancing the employer's operational needs against the employees' right to fair and stable working conditions. It remains a crucial precedent for both employers and employees navigating the complexities of modifying employment terms in Japan.