Chanel in a Snack Bar? Japan's Supreme Court on 'Broad-Sense Confusion' and Famous Brands

Judgment Date: September 10, 1998

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

Case Number: Heisei 7 (O) No. 637 (Claim for Prohibition of Unfair Competitive Acts)

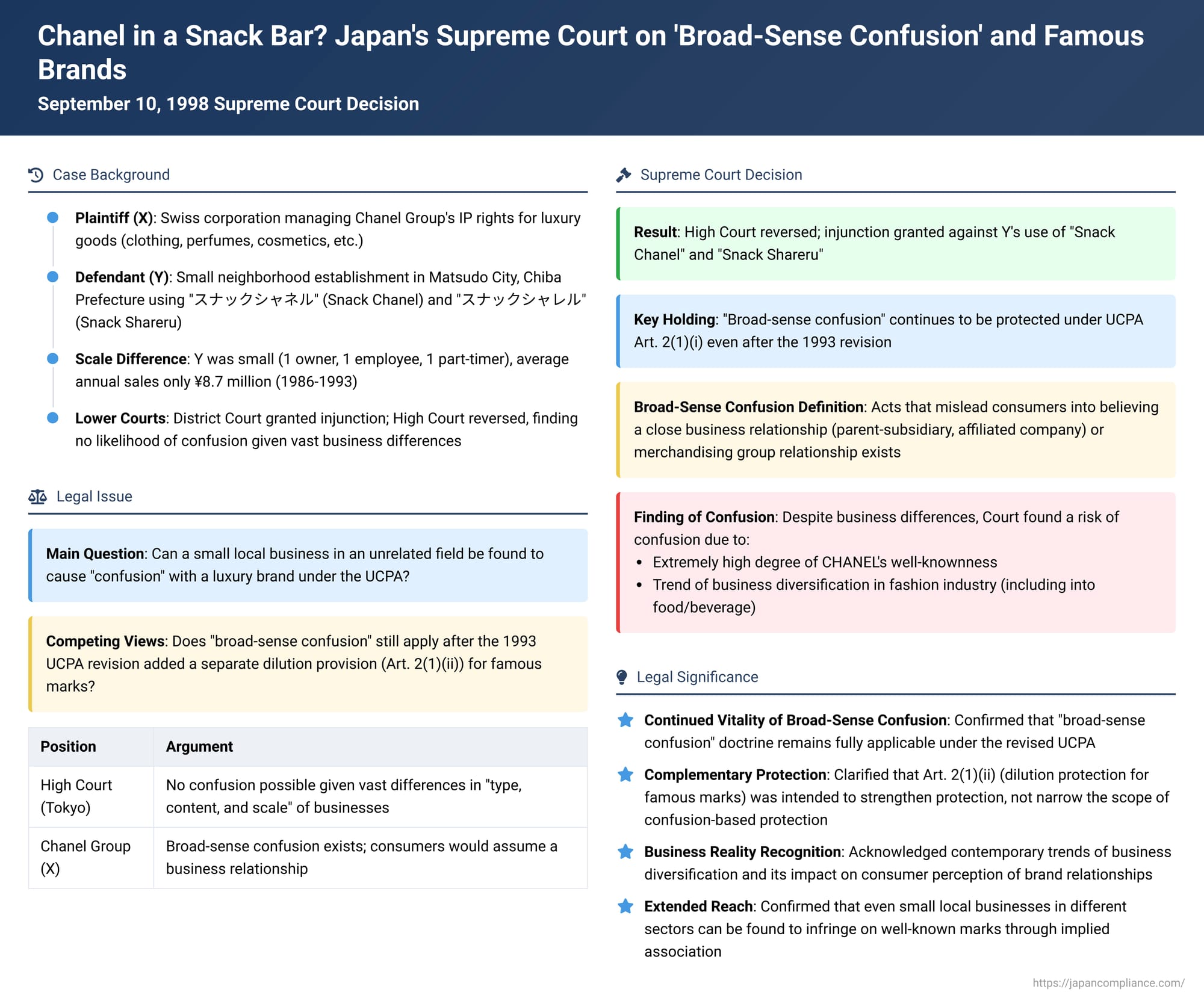

The "Snack Chanel" case (スナックシャネル事件), decided by the Japanese Supreme Court in 1998, is a pivotal judgment that reinforced the scope of protection for well-known brands under Japan's Unfair Competition Prevention Act (UCPA). The Court notably affirmed that the concept of "broad-sense confusion" (広義の混同 - kōgi no kondō)—where consumers mistakenly believe a business affiliation or sponsorship exists, even if they don't confuse the entities outright—remains a vital part of UCPA Article 2, Paragraph 1, Item 1. This was significant because it came after the 1993 revision of the UCPA, which had introduced a new, separate provision (Article 2, Paragraph 1, Item 2) to protect famous marks against dilution, even without proof of confusion. The Snack Chanel decision clarified that this new provision did not narrow the existing protections for "well-known" marks under the confusion-based standard.

The "Chanel" Brand vs. "Snack Chanel": A Clash of Worlds

The factual background presented a stark contrast in the nature and scale of the businesses involved:

- The Plaintiff (Company X): Company X was a Swiss corporation responsible for managing the intellectual property rights of the globally renowned "Chanel Group." The Chanel Group, a bastion of Parisian haute couture, is famous worldwide for its luxury goods, including high-fashion women's clothing, perfumes, cosmetics, handbags, shoes, accessories, and watches, all marketed under the iconic "CHANEL" indication. The "CHANEL" brand had been well-known (周知 - shūchi) in Japan since the early 1950s and was universally associated by consumers with an image of high quality and luxury. The Court also noted a prevailing trend in the fashion industry, to which the Chanel Group belonged, for companies to diversify their operations, including expanding into the food and beverage sector.

- The Defendant (Company Y): Company Y operated a small neighborhood establishment in Matsudo City, Chiba Prefecture. This business used the indications "スナックシャネル" (Snack Chanel) and, after the lawsuit was initiated, also "スナックシャレル" (Snack Shareru – a slight phonetic variation) on its signboards (collectively, "Y's Business Indications"). Company Y's operation was modest: typically staffed by Y, one employee, and one part-time worker, serving a few groups of customers daily. Its average annual sales between 1986 and 1993 were approximately JPY 8.7 million. This was a world away from the global luxury empire of the Chanel Group.

Company X sued Company Y, alleging that Y's use of "Snack Chanel" and "Snack Shareru" constituted unfair competition. The claim was initially based on Article 1, Paragraph 1, Item 2 of the old UCPA (pre-1993 revision), which prohibited the use of a business indication identical or similar to another's well-known business indication in a way that caused confusion. Company X sought an injunction to stop Y's use of these names and also claimed monetary damages.

Lower Court Rulings:

- First Instance (Chiba District Court, Matsudo Branch): The District Court partially found in favor of Company X, granting an injunction against the use of "Snack Chanel" and awarding some damages.

- Second Instance (Tokyo High Court): On appeal (Company X appealed on the quantum of damages, and Company Y filed a cross-appeal), the Tokyo High Court reversed the first instance decision and dismissed Company X's claims entirely. The High Court, while acknowledging the legal concept of "broad-sense confusion," ultimately found that it did not apply in this case. It reasoned that given the vast differences in the "type, content, and scale" of Company Y's business (a small local snack bar) compared to the Chanel Group's business (a global purveyor of luxury goods), it was "hardly conceivable that general consumers would misunderstand Company Y as having any business, economic, or organizational relationship" with the Chanel Group. Thus, the High Court concluded there was no likelihood of actionable confusion.

Company X appealed this High Court decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Reversal: Broad-Sense Confusion Reaffirmed and Applied

The Supreme Court partially overturned the Tokyo High Court's decision. It found that an injunction should be granted against Company Y's use of "Snack Chanel" and "Snack Shareru" and remanded the damages portion of the case to the High Court for recalculation.

I. Reiteration of "Broad-Sense Confusion" under the Old UCPA:

The Court began by referencing its own established precedents, notably the Nippon Woman Power case (1983) and the Football Symbol Mark case (1984). These cases had firmly established that "acts causing confusion" under the old UCPA Article 1, Paragraph 1, Item 2 were not limited to "narrow-sense confusion" (where consumers mistake one business entity for another entirely). Instead, the term also encompassed "broad-sense confusion," which includes acts that mislead consumers into believing that:

- A close business relationship exists between the parties (e.g., that of a parent company and subsidiary, or an affiliated company).

- The parties belong to the same group conducting a merchandising business under a common indication.

The Court also reiterated that a direct competitive relationship between the plaintiff and defendant is not a necessary prerequisite for such confusion to arise.

II. "Broad-Sense Confusion" Applies Equally under the New (Post-1993) UCPA Article 2(1)(i):

A crucial aspect of the Snack Chanel judgment was its clarification that this understanding of broad-sense confusion remains fully applicable under the revised UCPA, which came into effect in 1993. (Due to transitional provisions, the new UCPA was applicable to the Supreme Court's decision in this case). The specific provision in the new law is Article 2, Paragraph 1, Item 1.

The Supreme Court explicitly held that the phrase "acts causing confusion" in the new UCPA Article 2(1)(i) should be interpreted identically to how it was interpreted under the old law's Article 1(1)(ii)—meaning it continues to include broad-sense confusion.

The Court provided a three-part rationale for this consistency:

- Same Legislative Purpose: Both the old provision and the new Article 2(1)(i) share the same fundamental purpose: to prevent the legitimate interests of users of well-known business indications from being unjustly harmed by the unauthorized use of identical or similar indications by others.

- Continued Need for Protection: The prior Supreme Court rulings that established the doctrine of broad-sense confusion were grounded in the evolving economic and social landscape. This included factors like increasing business diversification, the formation of corporate groups united by common branding, and the rise of powerful, famous brands. The Court reasoned that the need to protect well-known business indications from such broader forms of misassociation remains undiminished under the new UCPA.

- Effect of the New Article 2(1)(ii): The 1993 UCPA revision introduced a new provision, Article 2, Paragraph 1, Item 2. This new item provides protection for famous (著名 - chomei, a higher standard than merely "well-known") indications against acts such as dilution or tarnishment, even if there is no likelihood of confusion. The Supreme Court stated that the creation of this new, distinct cause of action for famous marks was intended to strengthen and expand the protection for highly reputed indications. It was not intended to, and should not be interpreted as, narrowing the scope of protection afforded to "well-known" indications under Article 2(1)(i) (e.g., by excluding broad-sense confusion from the ambit of Art. 2(1)(i)).

III. Finding Broad-Sense Confusion in the "Snack Chanel" Case:

Applying these principles, the Supreme Court then assessed the specific facts of the dispute:

- While acknowledging that the nature and scale of Company Y's snack bar business were indeed different from the Chanel Group's luxury goods operations, the Court gave significant weight to two factors:

- The extremely high degree of well-knownness of the "CHANEL" indication in Japan.

- The recognized trend of business diversification within the fashion industry, where it was not uncommon for fashion houses to expand into related lifestyle areas, including the food and beverage sector.

- Conclusion on Confusion: Based on these considerations, the Supreme Court concluded: "Under the factual circumstances of this case, the use of Y's Business Indications ('Snack Chanel,' 'Snack Shareru') by Company Y created a risk that general consumers would misunderstand that a close business relationship or a relationship of belonging to the same merchandising group existed between Company Y and the enterprises of the Chanel Group."

Therefore, the Supreme Court held that Company Y's use of its business indications constituted an "act causing confusion" under (the new) UCPA Article 2, Paragraph 1, Item 1, and thereby infringed upon Company X's business interests.

Understanding Broad-Sense Confusion in the Post-Revision UCPA Era

The Snack Chanel decision is particularly important for affirming the continued vitality of the broad-sense confusion doctrine under UCPA Article 2(1)(i) even after the 1993 introduction of Article 2(1)(ii).

- What is "Broad-Sense Confusion"?

- Narrow-sense confusion typically occurs when consumers mistake the defendant's business directly for the plaintiff's business. This often, though not always, implies a competitive relationship.

- Broad-sense confusion, as defined by the Supreme Court, occurs when consumers, while perhaps recognizing the plaintiff and defendant as distinct entities, are nonetheless misled into believing there is some form of significant commercial link between them. This could be a belief that one is a parent company or subsidiary of the other, that they are part of the same affiliated group, or that the defendant is an authorized licensee or otherwise officially connected to the plaintiff's well-known brand or merchandising activities.

- The Challenge of Dilution/Tarnishment under the Old UCPA: The PDF commentary explains that before the 1993 UCPA revision, it was often difficult to legally address situations where a famous mark was used by another on unrelated and often lower-quality or unsavory goods or services, thereby tarnishing the famous mark's image or diluting its distinctiveness (these are often called "mark tarnishment/dilution" acts - 標章汚染・希薄化行為 - hyōshō osen・kihakuka kōi). The old UCPA was primarily based on preventing confusion. In cases where actual consumer confusion about source or affiliation was tenuous, but the harm to the famous mark's reputation was evident, courts sometimes "stretched" the concept of broad-sense confusion to grant relief. Examples cited include the Yodobashi Porno case, the Nina Ricci Kissa (cafe) case, the Pornoland Disney case, and a Love Hotel Chanel case. However, this expansive application of "confusion" was criticized by some as doctrinally strained, and indeed, other courts sometimes denied broad-sense confusion when the businesses were too disparate. The Tokyo High Court in the Snack Chanel case itself had adopted such a more restrictive view.

- The Role of the New UCPA Article 2(1)(ii): The introduction of Article 2(1)(ii) in the 1993 UCPA was specifically intended to provide a more direct legal basis for protecting famous indications against acts like dilution, free-riding, or tarnishment, without the plaintiff needing to prove a likelihood of confusion. The rationale was that for marks that achieve a very high level of fame, the primary harm from unauthorized use on dissimilar goods/services is often to the mark's inherent selling power, uniqueness, and positive associations, rather than direct consumer confusion about source.

- Why Article 2(1)(i) and Broad-Sense Confusion Still Matter: The Supreme Court in Snack Chanel made it clear that the new Article 2(1)(ii) was meant to be an additional layer of protection for famous marks, not a provision that narrowed the existing scope of Article 2(1)(i) for "well-known" marks (a threshold generally considered lower than "famous"). Thus, if a mark is "well-known" but perhaps not "famous" enough for Art. 2(1)(ii), or if the plaintiff chooses to plead under Art. 2(1)(i), the doctrine of broad-sense confusion remains fully applicable. The Supreme Court's emphasis on continued business diversification trends supports the ongoing need for this type of protection.

- Ongoing Debate and Critique: The Snack Chanel decision, by finding broad-sense confusion plausible despite the considerable differences in the nature and scale of the businesses, could be seen by some as continuing a rather expansive interpretation of "broad-sense confusion." The PDF commentary alludes to a critique by Professor Tamura, suggesting that cases involving very tenuous links of confusion, especially with highly famous marks, might be more appropriately handled under Article 2(1)(ii) (which allows for a more direct balancing of interests when confusion is not the central issue). Over-stretching Article 2(1)(i) to cover such non-obvious confusion scenarios might, in this view, bypass the specific design and intent of Article 2(1)(ii). If Article 2(1)(ii) itself has perceived shortcomings in its current form that lead courts to rely on an expansive Art. 2(1)(i), then perhaps Article 2(1)(ii) should be revisited.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's judgment in the Snack Chanel case robustly reaffirmed the doctrine of "broad-sense confusion" as a cornerstone of unfair competition protection in Japan under Article 2, Paragraph 1, Item 1 of the Unfair Competition Prevention Act. It clarified that even with the introduction of separate protections for "famous" marks against dilution, "well-known" marks continue to be shielded from uses that, while not causing direct source confusion, are likely to mislead consumers into believing there is an affiliation, sponsorship, or other significant commercial relationship with the owner of the well-known indication. By considering factors such as the extreme fame of the "CHANEL" brand and prevailing industry trends towards diversification, the Court demonstrated that even a small, local business using a globally recognized luxury brand name for vastly different services could indeed trigger this form of actionable confusion. The decision underscores the UCPA's commitment to protecting established business goodwill against a wide spectrum of misleading commercial practices.