Challenging Withholding Tax: Rights of Employers and Employees under Japanese Law

A First Petty Bench Ruling from December 24, 1970

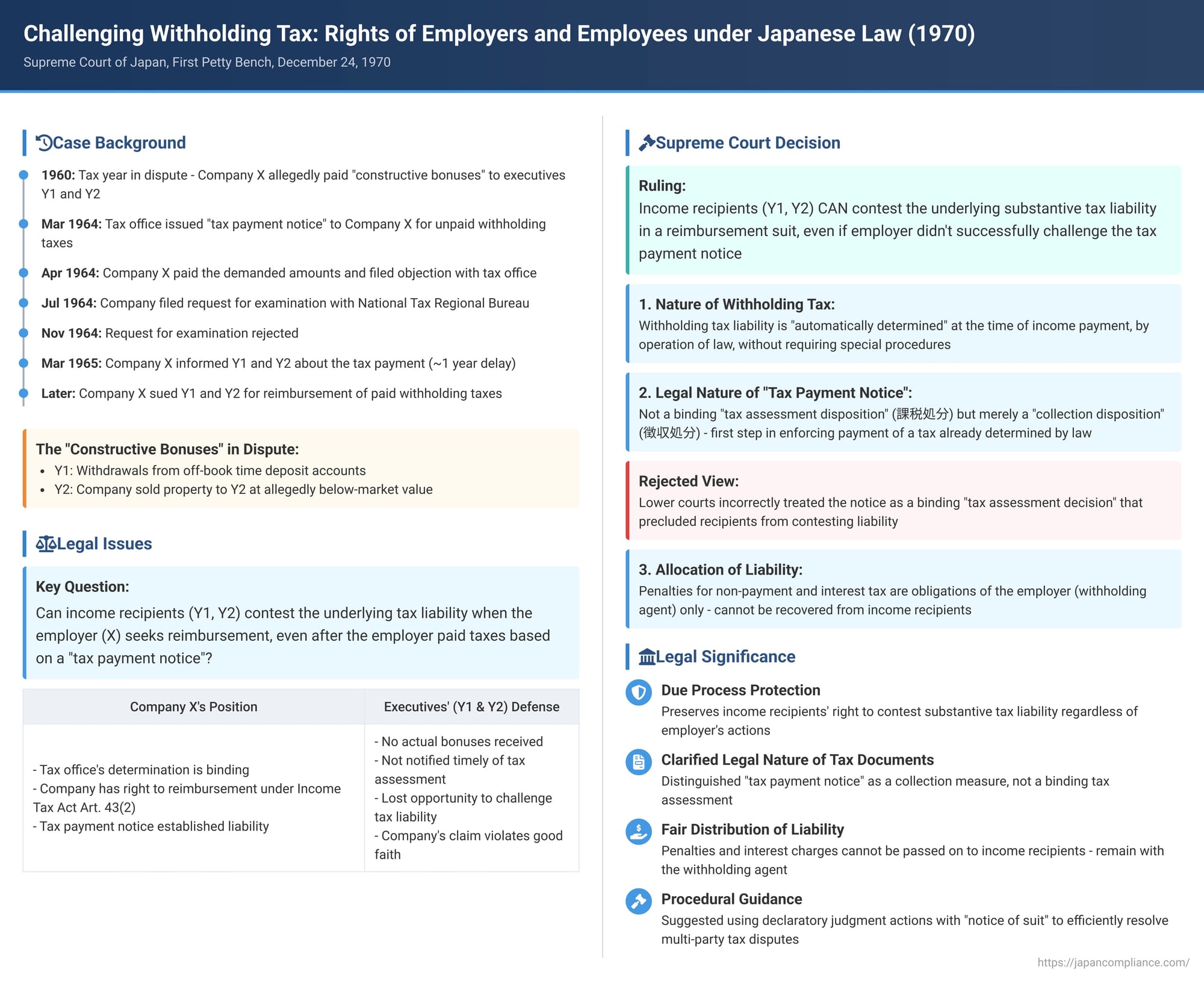

The withholding tax system, where employers deduct income taxes directly from employees' salaries and pay them to the government, is a common feature of modern tax administration. It's generally efficient, but complexities can arise when tax authorities determine that certain payments, not initially treated as salary or bonus by a company, should indeed be classified as taxable income subject to withholding. A 1970 Supreme Court of Japan decision by its First Petty Bench (Showa 43 (O) No. 258) delved into the legal ramifications of such a situation, particularly clarifying the nature of the "tax payment notice" issued to employers and the rights of both employers and employees to dispute the underlying tax liability.

The Disputed Bonuses and Tax Demands

The case involved Company X (the appellee) and two of its former executives, Y1 and Y2 (the appellants). Following a tax investigation into Company X's income for fiscal year 1960, the chief of the competent tax office, A, made a determination on March 10, 1964. A concluded that certain withdrawals from off-book time deposit accounts by Y1, and losses incurred by the company from selling property to Y2 at a low value, constituted "constructive bonuses" (認定賞与 - nintei shōyo) paid by Company X to Y1 and Y2, respectively.

As a result of this determination, A issued a "tax payment notice" (納税の告知 - nōzei no kokuchi) to Company X. This notice, a formal demand for payment, asserted that Company X, as the withholding agent (徴収義務者 - chōshū gimusha), was liable for withholding income tax on these deemed bonuses, as well as for non-payment penalty tax (不納付加算税 - funōfu kasanzie) and interest tax (利子税 - rishizei). Company X complied and paid the amounts demanded by the government on April 9, 1964, and a further amount for new interest tax on August 14, 1964.

Company X did attempt to challenge the tax office's determination through administrative appeals. It filed an objection (異議申立て - igi mōshitate) with the tax office chief A on April 11, 1964, which was rejected on June 18 of that year. Company X then pursued a request for examination (審査請求 - shinsa seikyū) with the competent National Tax Regional Bureau, B, on July 11, but this too was rejected on November 26. Importantly, Company X did not subsequently file a lawsuit in court to seek the annulment of the tax payment notice.

A crucial fact was that Company X did not inform its former executives, Y1 and Y2, about these tax assessments, payments, or the unsuccessful appeals until around March 8, 1965, nearly a year after the initial payments were made.

The Lawsuit: Company Seeks Reimbursement from Executives

Having paid the assessed withholding taxes and associated charges, Company X filed a lawsuit against Y1 and Y2. The company sought to recover the amounts it had paid to the government, basing its claim on Article 43, paragraph 2 of the old Income Tax Act (a provision which generally allowed a payer who had withheld and paid tax to seek reimbursement from the income recipient).

Y1 and Y2 raised several defenses:

- They argued that, substantively, no taxable bonus had actually been received. Y1 claimed the off-book deposits were personal funds, and Y2 argued the property sale was not at an unduly low value. Thus, they contended there was no underlying income subject to withholding tax.

- They asserted that Company X's failure to inform them in a timely manner about the tax office's assessment and the subsequent payment deprived them of the opportunity to cooperate in the company's tax appeals or to take their own steps to challenge the assessment. They argued that Company X, by failing to provide such notice and then pursuing reimbursement after the administrative appeal routes were exhausted (and the time for judicial appeal of the notice had likely passed for the company), was acting in violation of the principle of good faith and was abusing its rights.

- Alternatively, Y1 and Y2 claimed that Company X's failure to notify them constituted a tortious act that deprived them of their constitutional right to access the courts (under Article 32 of the Constitution) to contest the tax determination. They argued they suffered damages equal to the amount Company X was claiming and sought to offset this against the company's demand.

The lower courts—the Nagoya District Court (first instance) and the Nagoya High Court (second instance)—ruled in favor of Company X. They largely rejected Y1 and Y2's defenses, generally treating the tax office chief's action as a binding "tax assessment decision" (課税決定 - kazei kettei) and implying that since Y1 and Y2 eventually became aware of this "income tax decision" (所得税の決定 - shotokuzei no kettei), they could have initiated their own appeals or legal actions at that point. Y1 and Y2 appealed this outcome to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision of December 24, 1970

The Supreme Court partially quashed and modified the lower court judgments concerning the amounts recoverable (specifically regarding penalties and the interest rate on delay damages) but, more importantly, it provided a detailed exposition of the legal nature of the withholding tax system and the "tax payment notice," which significantly impacted the rights of the parties.

Key Rulings on Withholding Tax Mechanics:

- Withholding Tax is "Automatically Determined": The Court first clarified a fundamental aspect of Japan's withholding income tax system. When income subject to withholding is paid, the payer (the employer, Company X in this case) incurs an obligation to withhold the income tax and remit it to the state. This tax liability of the payer, and the precise amount of tax to be withheld, "is established at the time of the said income payment, and simultaneously with its establishment, the tax amount to be paid is determined without requiring special procedures" (判旨1). This means the tax amount is considered "automatically determined" (自動的に確定する - jidōteki ni kakutei suru) by operation of law, based on the amount of income paid and the applicable tax rates and rules. This automatic determination is distinct from tax systems where liability is only fixed after a taxpayer's declaration or a formal assessment disposition (like a correction, determination, or imposition decision) by the tax authorities. This principle, the Court noted, is an inherent premise of the withholding tax system, even predating its explicit codification in Article 15 of the General Act of National Taxes (国税通則法 - Kokuzei Tsūsoku Hō).

- "Tax Payment Notice" is Not a Tax Assessment Disposition: The Court then addressed the legal nature of the "tax payment notice" (nōzei no kokuchi) issued by the tax office chief (A) to Company X. When a tax office chief believes that a payer has underpaid withholding tax or has failed to pay it, this view is officially communicated to the payer through such a notice. The Court acknowledged that this notice "presents an appearance as if it were analogous to a correction or determination in the case of a self-assessment tax system" (判旨3). However, because the amount of withholding income tax is, as explained above, "automatically determined," it is not determined or fixed by this subsequent tax payment notice. Therefore, the Court held, "this tax payment notice should be said not to possess the character of a tax assessment disposition (課税処分たる性質を有しない - kazei shobun taru seishitsu o yūshinai) such as a correction or determination" (判旨3).

- Consequences of this Distinction for Payer and Recipient: The Court elaborated on the implications of the notice not being a tax assessment. If it were an assessment, its legal finality (if not successfully annulled by the payer through litigation) would definitively establish the payer's obligation to withhold and pay the specified amount. This, in turn, would mean that the income recipient (Y1 and Y2) could not then refuse the payer's claim for reimbursement. The tax liability of both the payer (as withholding agent) and the recipient (as the ultimate taxpayer on that income) would be effectively fixed by the notice to the payer. However, the Court found this outcome "not permissible under current law" (判旨3). It would contradict the fundamental principle that withholding tax liability crystallizes at the time of income payment. Furthermore, if a notice to the payer were to finalize the recipient's tax liability as well, then logically, such a notice should be served on both the payer and the recipient. Yet, tax law designates only the payer as the "taxpayer" (納税者 - nōzeisha) for the purposes of the withholding obligation, and the tax payment notice is only served on the payer. To conclude that a notice served only on the payer could, with binding legal force (kōteiryoku), determine the scope of the recipient's tax liability without their knowledge, was "an outcome that cannot possibly be construed as intended by the law" (判旨3).

- Nature of the Notice as a Collection Measure and the Payer's Right to Appeal It: Generally, a "tax payment notice" (as stipulated in Article 36 of the National Tax Collection Act) is the first step in the tax collection process for delinquent taxes and is an indispensable prerequisite for subsequent enforcement actions like seizure of assets. Its nature is that of a demand for payment of an already determined national tax liability—it is a "collection disposition" (徴収処分 - chōshū shobun). (An exception exists for taxes under the "official assessment system" - 賦課課税方式 fuka kazei hōshiki - where the notice of tax due can simultaneously serve as the tax amount determination). For withholding income tax, since the tax amount is automatically determined at the time of payment, the subsequent "tax payment notice" is the first official expression of the tax office chief's opinion as to what that automatically determined amount is. If the payer disagrees with this amount, they can challenge it to prevent collection. The Court stated that the payer can do this through administrative appeals (objection or request for examination under the General Act of National Taxes) and also by filing an "annulment lawsuit" (kōkoku soshō) against the notice. In such a lawsuit, the payer can dispute the existence or scope of their underlying withholding tax obligation, as there is no prior binding assessment disposition that would preclude them from doing so (判旨4).

- Recipient's Right to Contest Substantive Liability in Reimbursement Suit: This was the crucial point for Y1 and Y2. Since the "tax payment notice" issued to Company X (the payer) was merely a collection disposition and not a tax assessment that definitively fixed the payer's substantive tax liability, any failure by Company X to successfully appeal that notice "can have no effect whatsoever on the existence or scope of the withholding tax liability of the recipients" (Y1 and Y2) (判旨5).

Therefore, when Company X (the payer), having paid the tax demanded by the notice, sought reimbursement from Y1 and Y2 (the recipients), Y1 and Y2 were fully entitled to "dispute their own non-liability for withholding tax or the scope of such liability, and to refuse all or part of the payer's claim" (判旨5).

The Supreme Court found that the lower courts had misunderstood the legal nature of the "tax payment notice," incorrectly treating it as a "tax assessment decision." Consequently, the lower courts had erred in concluding that Y1 and Y2's opportunity to contest the tax was foreclosed. The Supreme Court clarified that Company X's failure to notify Y1 and Y2 earlier of the tax office's actions did not, in fact, prejudice Y1 and Y2's fundamental right to contest the substantive basis of their alleged tax liability (i.e., whether the payments were indeed taxable bonuses to them). This substantive defense could and should have been fully considered in the civil reimbursement suit initiated by Company X.

Regarding Penalties and Interest:

The Supreme Court also ruled that penalties for non-payment (不納付加算税 - funōfu kasanzie) and interest tax (利子税 - rishizei) are statutory obligations imposed on the payer (Company X) for its own failure to properly withhold and remit tax by the due date. These are not part of the tax liability of the recipients (Y1 and Y2). Therefore, Company X could not seek reimbursement from Y1 and Y2 for these additional amounts. Any delay damages Company X could claim from Y1 and Y2 on the principal amount of withholding tax (if Y1 and Y2 were found liable for it) would be calculated at the general civil statutory interest rate (then 5% per annum), not the higher commercial statutory rate.

Significance of the Ruling

This 1970 Supreme Court decision holds considerable importance in Japanese tax law:

- It definitively clarified the legal nature of the "tax payment notice" (nōzei no kokuchi) in the context of withholding income tax, distinguishing it from a formal tax assessment disposition (kazei shobun). It is primarily a "collection disposition."

- It robustly protected the substantive due process rights of income recipients (employees/executives) by affirming their right to contest the underlying basis of their withholding tax liability in a civil suit for reimbursement by the payer, even if the payer had not successfully challenged the tax payment notice received from the tax authorities. The administrative process between the tax authority and the payer does not, by itself, finalize the recipient's substantive tax obligations.

- The judgment provided clear guidance on the allocation of responsibility for ancillary tax liabilities such as non-payment penalties and interest tax, placing them firmly on the withholding agent (payer) for their own procedural failings.

- The Court also offered a procedural suggestion for payers facing potential disputes on two fronts (with the tax office over the notice, and with the recipient over reimbursement): the payer could file a declaratory judgment action against the state concerning their own tax liability and give "notice of suit" (soshō kokuchi) to the recipient, thereby seeking to bind the recipient to the outcome or at least share responsibility for establishing the facts.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's judgment in this case meticulously dissected the mechanics of the withholding income tax system in Japan, particularly the role and legal effect of a "tax payment notice." By characterizing it as a collection measure rather than a substantive tax assessment against the payer that would also bind the recipient, the Court preserved the crucial right of the income recipient to have their actual tax liability determined on its merits in appropriate legal proceedings. This decision underscores a careful balance: while the withholding system is designed for efficient tax collection by placing primary compliance duties on the payer, it does not strip the ultimate taxpayer (the income recipient) of their right to dispute the substantive basis of a tax claimed from them. It also highlights the importance of clear distinctions between procedural collection acts and substantive liability-creating acts in tax administration.