Challenging Tax Assessments: Japanese Supreme Court Expands Rights of Secondarily Liable Parties

Judgment Date: January 19, 2006

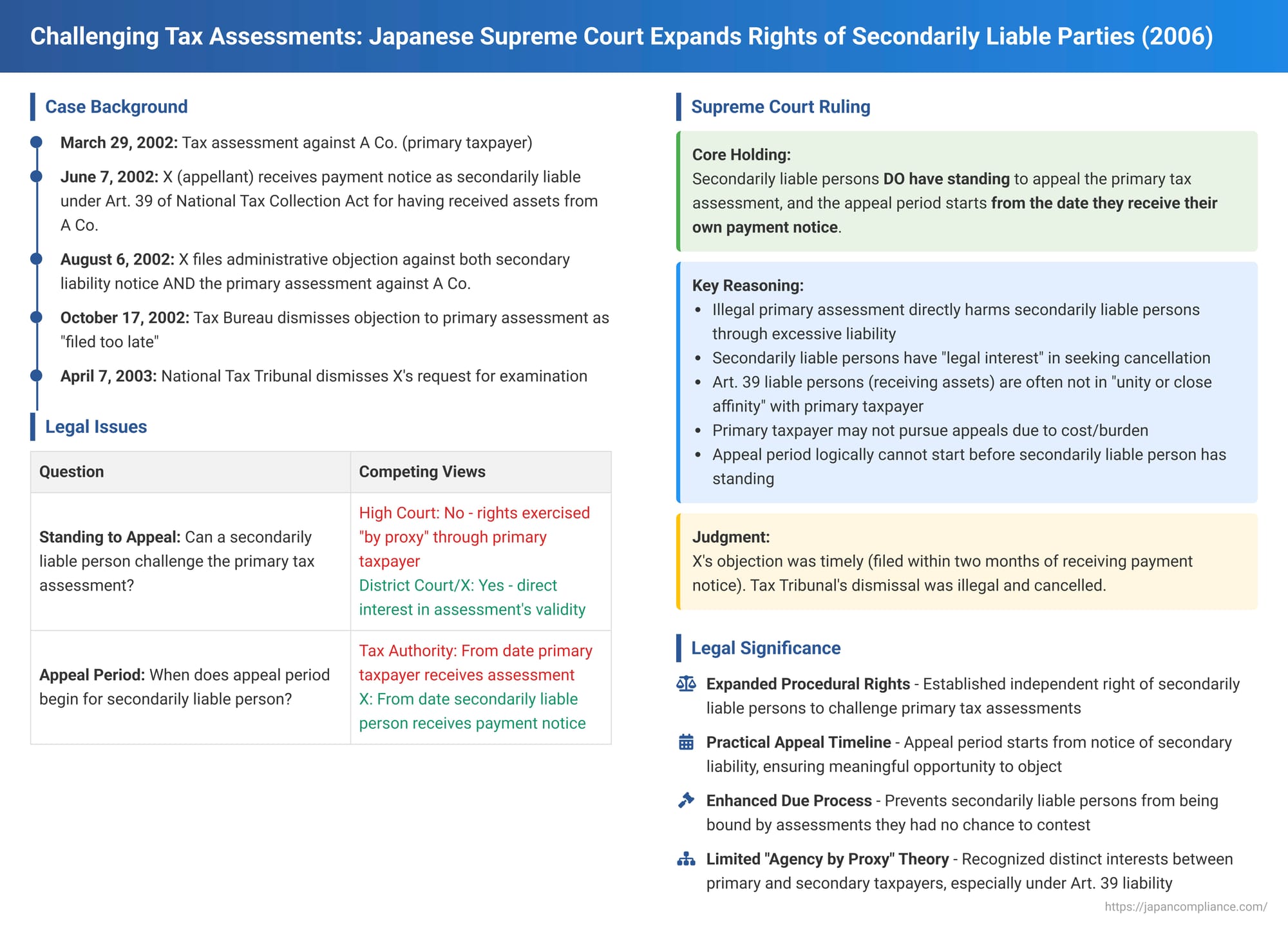

In a significant decision for Japanese tax procedure, the First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan clarified and expanded the rights of individuals and entities held secondarily liable for another taxpayer's delinquent taxes. The Court ruled that such secondarily liable parties have the standing to administratively appeal the original (primary) tax assessment levied against the main taxpayer, and crucially, that the time limit for filing such an appeal begins when the secondarily liable party receives their own notice of secondary liability, not when the primary taxpayer was initially assessed.

Background: Secondary Tax Liability and a Disputed Appeal Period

The appellant, X, was subjected to secondary tax liability under Article 39 of Japan's National Tax Collection Act. This provision allows tax authorities to pursue collection from a third party who received assets from a delinquent taxpayer either gratuitously or for a significantly low price, if the delinquent taxpayer's remaining assets are insufficient to cover their tax debt.

The sequence of events was as follows:

- Primary Tax Assessment on A Co. On March 29, 2002, the Kojimachi Tax Office Chief issued a corporate tax assessment (including non-filing penalties) against "A Co." for unpaid taxes. This "primary tax assessment" was formally notified to A Co. on April 3, 2002.

- X's Transaction with A Co. X had received shares from A Co. under circumstances that allegedly made X liable under Article 39 (i.e., a low-value transfer).

- Notice of Secondary Liability to X: On June 7, 2002, the Tokyo Regional Tax Bureau Chief issued a "payment notice" (nōfu kokuchi - 納付告知) to X. This notice informed X of their secondary tax liability for A Co.'s delinquent national taxes. The notice was delivered to X on June 8, 2002.

- X's Administrative Appeals: On August 6, 2002—within two months of receiving the payment notice for secondary liability—X filed an administrative objection (igi mōshitate - 異議申立て) with the Tokyo Regional Tax Bureau Chief. X objected not only to the payment notice imposing secondary liability on X but also, critically, to the underlying primary tax assessment that had been issued against A Co.

- Dismissal of Objection to Primary Assessment: On October 17, 2002, the Tokyo Regional Tax Bureau Chief dismissed X's objection concerning the primary tax assessment against A Co. The reason given was that the objection was filed out of time. The tax authority contended that the two-month period (the standard appeal period at the time, now generally three months under the Act on General Rules for National Taxes) for objecting to the primary tax assessment began when A Co. was notified on April 3, 2002, meaning X's objection in August was too late. (The objection to X's own secondary liability notice led to a partial modification of the amount but is not the focus here).

- Dismissal of Request for Examination: X then filed a request for examination (shinsa seikyū - 審査請求) with the Head of the National Tax Tribunal (Y, the appellee, representing the tax authority) seeking to overturn the primary tax assessment against A Co. On April 7, 2003, the National Tax Tribunal dismissed this request. It reasoned that X's initial objection to the primary tax assessment had been untimely and therefore invalid, meaning the request for examination was not preceded by a legally proper objection, a prerequisite for review by the Tribunal.

- X's Lawsuit: X filed a lawsuit seeking the cancellation of the National Tax Tribunal's decision to dismiss the request for examination.

(It's also noted that A Co. itself had filed an untimely objection to the primary tax assessment, which was dismissed, and A Co. later withdrew its subsequent request for examination.)

The Core Legal Issues Before the Courts

The case presented two fundamental questions concerning the procedural rights of a party held secondarily liable for taxes:

- Standing to Appeal: Does a person subjected to secondary tax liability (specifically under Article 39 of the National Tax Collection Act) have the legal standing to file an administrative appeal challenging the merits of the primary tax assessment issued against the original, delinquent taxpayer?

- Commencement of Appeal Period: If such standing exists, when does the statutory period for filing this appeal begin for the secondarily liable person? Does it start from the date the primary taxpayer was notified of the original assessment, or from the date the secondarily liable person received their own notice of secondary liability?

Lower Court Rulings:

- The Tokyo District Court (first instance) ruled in favor of X. It affirmed that a secondarily liable person does have standing to appeal the primary tax assessment. Crucially, it held that the appeal period for such a person starts from the day after they receive the payment notice establishing their own secondary liability. Thus, X's objection was timely.

- The Tokyo High Court (appellate court) reversed this decision, ruling against X. It held that a secondarily liable person lacks standing to appeal the primary assessment. The High Court's reasoning was that the right to contest the primary tax liability is, in a sense, "exercised by proxy" by the primary taxpayer. Once the collection phase for the primary tax debt is reached, the secondarily liable person is merely obligated to fulfill that established liability and cannot independently challenge its basis.

X appealed the High Court's decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Expanding Procedural Rights

The Supreme Court overturned the Tokyo High Court's decision and effectively reinstated the first instance court's judgment in favor of X, affirming X's right to challenge the primary tax assessment within a timeframe calculated from the notice of X's own secondary liability.

I. Standing of the Secondarily Liable Person to Appeal the Primary Tax Assessment

The Court firmly established the standing of a person in X's position:

- Impact of Primary Assessment on Secondary Liability: The Court began by noting that when a primary tax liability is determined by a primary tax assessment, this assessment forms the fundamental basis for the secondary tax liability. "If an illegal primary tax assessment leads to an excessive determination of the primary tax liability, the amount uncollectible from the original taxpayer will naturally be larger, and the scope of the secondary tax liability will also become excessive. In such cases, the secondarily liable person is at risk of suffering direct and concrete prejudice."

- Legal Interest in Cancellation: Conversely, if the primary tax assessment is cancelled or reduced due to illegality, the secondary liability will correspondingly be extinguished or reduced. "Therefore," the Court stated, "the secondarily liable person has their rights or legally protected interests infringed, or is at risk of such inevitable infringement, by the primary tax assessment, and has a legal interest in seeking its cancellation to recover from such infringement."

- Conclusion on Standing: "Thus, it is appropriate to conclude that a person subjected to secondary tax liability under Article 39 of the National Tax Collection Act can file an administrative appeal against the primary tax assessment pursuant to Article 75 of the Act on General Rules for National Taxes."

II. Critiquing the "Agency by Proxy" Theory

The Supreme Court specifically addressed and largely rejected the High Court's theory that the primary taxpayer "exercises by proxy" the secondary taxpayer's right to appeal, especially in the context of Article 39 secondary liability:

- While acknowledging that, abstractly, secondary liability is imposed on those with a special relationship to the primary taxpayer where shared responsibility seems fair, the nature of these relationships can vary. The Court found it inappropriate to completely negate the independent legal personality of the secondarily liable person in all scenarios.

- Specifically for Article 39 liability (arising from receiving property gratuitously or at low value), the secondarily liable person is merely a counterparty to a transaction. They are "not always in a relationship of unity or close affinity with the original taxpayer." The mere receipt of a benefit does not automatically justify treating them as identical for procedural purposes.

- Furthermore, the primary taxpayer, being delinquent, "may not necessarily pursue appeals or other legal challenges against the primary tax assessment, even if it is flawed, due to the burden of time and expense." Therefore, "it is difficult to assume that the secondary taxpayer's right to sue is adequately represented by the original taxpayer."

- The Court also noted that even if the primary tax liability was fixed by the primary taxpayer's own declaration (rather than an assessment), and the secondary taxpayer has no direct means to challenge that declaration, this shouldn't lead to denying them a remedy if their rights are infringed by an illegal exercise of administrative power.

III. Starting Point of the Appeal Period for the Secondarily Liable Person

This was the second crucial element of the decision:

- Standing Precedes Appeal Period Commencement: The Court reasoned that a person can only be deemed to have standing to appeal a primary tax assessment from the point at which "they have received a payment notice and their status as a secondarily liable person is confirmed, or at least from the point when they can objectively recognize that receiving such a notice establishing their secondary liability is certain."

- Illogicality of Premature Start: "Therefore, it would be illogical (hairi - 背理) for the appeal period to start running for such a person at a stage when they do not yet have standing to appeal [the primary assessment as it affects them]."

- Effect of the Payment Notice: For a person subject to Article 39 secondary liability, who may not have a close relationship with the primary taxpayer, they cannot reliably know they have standing to appeal until their own secondary liability is fixed by a payment notice. "However, once the payment notice is received, they become definitively aware of the existence of the primary tax assessment and the establishment of their own secondary liability. At that point, at least, they can clearly be said to 'have come to know that the disposition had been made' [quoting the statutory language for the start of the appeal period]."

- Conclusion on Start Date: "Thus, when a person subject to secondary tax liability under Article 39 of the National Tax Collection Act files an administrative appeal against the primary tax assessment, the phrase 'the day on which [the person] came to know that the disposition had been made' as stipulated in Article 77, Paragraph 1 of the Act on General Rules for National Taxes refers to the day on which the payment notice for secondary liability (service of the payment notice document) was made to the said secondarily liable person. The appeal period should be calculated as starting from the day following the date such payment notice was made."

Judgment and Its Broader Significance

Based on this reasoning, the Supreme Court found that X's objection to the primary tax assessment against A Co. was indeed filed within the statutory period, as it was filed within two months of X receiving the payment notice for secondary liability. The National Tax Tribunal's decision to dismiss X's request for examination (on grounds that the initial objection was untimely) was therefore illegal and should be cancelled. The Supreme Court reversed the High Court's judgment and, exercising its power of self-judgment (haki jihan - 破棄自判), effectively reinstated the first instance court's decision which had found X's appeal timely.

This 2006 Supreme Court judgment is of significant importance:

- Affirmation of Appeal Rights: It definitively establishes that individuals or entities held secondarily liable for taxes under Article 39 of the National Tax Collection Act have an independent legal standing to challenge the merits of the underlying primary tax assessment that forms the basis of their derivative liability.

- Clarification of Appeal Period for Secondary Parties: The ruling is crucial for its clear pronouncement that the statutory time limit for such an appeal begins when the secondarily liable party receives their own formal notice of secondary liability, not from the earlier date when the primary taxpayer was assessed. This ensures that the right to appeal is practical and meaningful, not illusory due to the expiry of a deadline before the secondary party is even formally implicated.

- Enhancement of Procedural Fairness: This decision significantly bolsters the procedural due process rights for a category of taxpayers who are drawn into tax disputes due to their dealings with, or relationship to, a primary delinquent taxpayer. It prevents them from being bound by a primary assessment they had no effective opportunity to contest.

- Limitation of the "Agency by Proxy" Rationale: The Court's careful differentiation of Article 39 secondary liability from potentially closer relationships (where an "agency by proxy" argument for appeal rights might be more tenable) shows a nuanced approach to different types of derivative tax liabilities.

Justice Izumi's Concurring Opinion

Justice Tokuji Izumi issued a concurring opinion, agreeing with the majority's conclusion on the timeliness of X's appeal but offering a slightly different legal rationale. He argued that a payment notice for secondary liability, while aimed at collecting the primary tax, also serves to newly establish and confirm the secondary taxpayer's own distinct tax liability. Therefore, the secondary taxpayer should be able to contest the legality of the primary tax assessment (as an embedded component of their own secondary liability) directly within an appeal against the payment notice issued to them. This would mean they might not necessarily need separate standing to appeal the primary assessment itself, but could raise its defects as a defense against their own secondary liability. Justice Izumi suggested that a prior Supreme Court precedent (from 1975), which held that secondary taxpayers could not dispute the established primary tax debt when appealing their own payment notice, should be reconsidered. The majority, however, opted to grant direct standing to appeal the primary assessment.

Overall, this Supreme Court judgment represents a significant development in protecting the rights of those affected by secondary tax liability, ensuring they have a fair opportunity to challenge the very basis of the obligation imposed upon them.