Challenging Progress: Why Citizens Couldn't Directly Sue Over a Shinkansen Plan Approval in 1970s Japan

Judgment Date: December 8, 1978

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

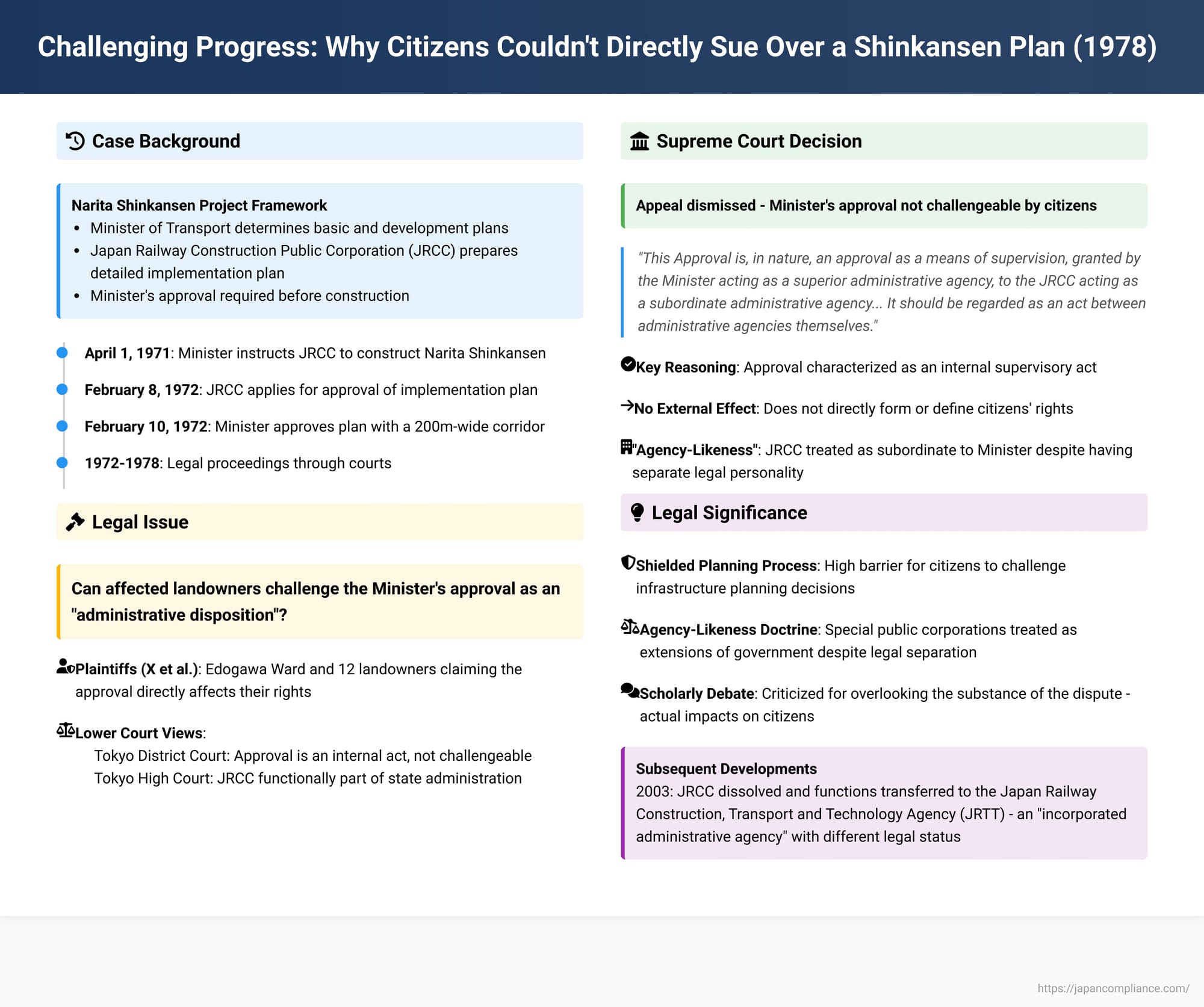

Can citizens directly challenge a governmental approval for a major public works project, like a Shinkansen (bullet train) line, when that approval is granted to a specially established public corporation? This was the central question in a pivotal 1978 Supreme Court case concerning the planned Narita Shinkansen. The Court's decision shed light on the legal status of such public corporations and the nature of ministerial approvals, ultimately restricting the avenues for direct legal recourse by affected residents.

The Framework for Shinkansen Construction and the Narita Plan

At the time, the Nationwide Shinkansen Railway Development Act (hereinafter "Shinkansen Act") laid out a specific procedure for building new bullet train lines. The Minister of Transport was responsible for determining basic plans (Article 5) and more detailed development plans (整備計画 - seibi keikaku, Article 7). Following this, the Minister would instruct the Japan Railway Construction Public Corporation (日本鉄道建設公団 - JRCC) to undertake the construction (Article 8). The JRCC, a "special public corporation" (特殊法人 - tokushu hōjin) established by law for specific public purposes, would then prepare a detailed "works implementation plan" (工事実施計画 - kōji jisshi keikaku), which required the Minister of Transport's approval (認可 - ninka) before construction could commence (Article 9).

On April 1, 1971, Y (the Minister of Transport) instructed the JRCC to construct the Narita Shinkansen line. Subsequently, on February 8, 1972, the JRCC applied to Y for approval of the "Works Implementation Plan Part 1" for the Tokyo-Narita Airport section of this new line. This approval (hereinafter "the Approval") was swiftly granted just two days later, on February 10, 1972.

The approved works implementation plan detailed various aspects of the project, including the route name, construction sections, total track length, and construction methodologies. Critically for local residents, the plan also indicated the proposed railway line's location on a 1/200,000 scale map with a line approximately 1mm wide. When translated to the actual ground, this seemingly narrow line represented a corridor about 200 meters wide, potentially impacting properties within this band.

The Landowners' Lawsuit

X et al. (a group including Edogawa Ward of Tokyo and 12 other individuals and entities who owned land within the planned Narita Shinkansen route) filed a lawsuit seeking the revocation of the Approval granted by Y (the Minister of Transport) to the JRCC. They aimed to stop the project by challenging the legal validity of this key ministerial green light.

The Journey Through the Lower Courts

First Instance Court (Tokyo District Court, December 23, 1972):

The Tokyo District Court dismissed the plaintiffs' lawsuit. The court characterized the Approval as an internal act between Y (the Minister) and the JRCC. It reasoned that the Approval served to confirm the plan devised by JRCC for essential matters concerning the Narita Shinkansen construction and to grant JRCC the authority to proceed with construction based on that plan. However, it was not considered a concrete "administrative disposition" (行政処分 - gyōsei shobun, an official act by an administrative agency that directly affects the rights and duties of citizens) aimed at specific members of the public. Furthermore, the court found that the Approval did not, by itself, have any impact on the rights and obligations of citizens and that the dispute lacked sufficient "ripeness" to be considered a litigious case. Therefore, it concluded that the Approval did not constitute an administrative disposition that could be challenged through a kōkoku appeal (抗告訴訟 - a type of lawsuit specifically designed to seek the revocation of an administrative disposition).

Appellate Court (Tokyo High Court, October 24, 1973):

The Tokyo High Court upheld the District Court's decision to dismiss the suit, also denying the "administrative disposition" nature of the Approval. The High Court elaborated on the status of the JRCC. It noted that while the JRCC was formally a legal entity independent of the state and distinct from national administrative organs, it should, in substance, be considered as one with the state. The High Court described the JRCC as a kind of government-affiliated agency, functionally constituting a subordinate organization to the Minister of Transport and forming part of the broader national administrative structure. Based on this characterization, the High Court employed reasoning similar to that later adopted by the Supreme Court to deny that the Approval was an externally challengeable administrative disposition.

X et al. appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Verdict: Appeal Dismissed

On December 8, 1978, the Supreme Court, Second Petty Bench, dismissed the appeal by X et al., upholding the lower courts' decisions. The costs of the appeal were to be borne by the appellants.

Unpacking the Supreme Court's Reasoning

The Supreme Court's reasoning was concise but definitive. It affirmed the High Court's judgment, stating:

"This Approval is, in nature, an approval as a means of supervision, granted by Y, the Minister of Transport, acting as a superior administrative agency, to the Japan Railway Construction Public Corporation, acting as a subordinate administrative agency, after examining the consistency of the submitted works implementation plan with the development plan (整備計画). It should be regarded as an act between administrative agencies themselves. It does not have external effect as an administrative act, nor does it entail the effect of directly forming the rights and duties of citizens or defining their scope. Therefore, the judgment of the lower court, which held that this Approval does not constitute an administrative disposition subject to a kōkoku appeal, can be affirmed as correct, and the lower court's judgment contains no illegality as argued by the appellants."

The Supreme Court further noted that the appellants' arguments concerning alleged unconstitutionality were premised on the assumption that the Approval directly formed or defined the rights and duties of citizens, a premise the Court found to be lacking. The Court dismissed the appellants' arguments as merely advancing their own unique interpretations to criticize the lower court's decision and, therefore, unadoptable.

Broader Implications and Scholarly Analysis

This Supreme Court decision is significant for its understanding of the legal status of special public corporations like the JRCC and its impact on citizens' ability to challenge large-scale public projects.

1. The "Agency-Likeness" of Special Public Corporations:

The ruling effectively denied the "administrative disposition" character of the Minister's approval by framing it as an internal supervisory act within the administrative hierarchy. This was based on viewing the JRCC not as a fully independent entity in this context, but as akin to a subordinate administrative organ to the Minister of Transport. The core idea is that interactions between such entities are internal to the government and not typically subject to judicial review initiated by third parties. The JRCC was thus placed in a position analogous to an agency within the administrative machinery of the state, and its relationship with the state regarding this approval was characterized as an internal administrative matter.

This concept of "agency-likeness" (gyōsei kikansei) leading to a denial of justiciability echoed in earlier precedents and academic theories.

- A 1959 Supreme Court case had similarly found that a fire chief's consent to a building permit application (given to the prefectural governor) was an internal act between administrative organs and not a disposition challengeable by citizens.

- The 1974 Supreme Court decision concerning the National Health Insurance system (discussed in a previous post) also characterized the relationship between a municipal insurer and the NHI Review Commission as analogous to that of subordinate and superior administrative agencies in the context of reviewing benefit decisions.

- Prominent administrative law scholar Professor Jiro Tanaka, writing before this judgment, had developed an academic concept of "independent administrative corporations" (a term distinct from the later statutory "incorporated administrative agencies"). He viewed these as proxy organs possessing a degree of unity with the state or local governments. Consequently, directives, permissions, or approvals from the state to such corporations were considered internal acts, not subject to ordinary administrative grievance appeals or kōkoku lawsuits.

The 1978 JRCC decision can be understood as aligning with this theoretical stream, emphasizing the JRCC's "agency-likeness" in its relationship with the state concerning the Shinkansen construction project and thereby denying the external, challengeable nature of the ministerial approval.

2. Criteria for "Agency-Likeness" and the Nature of the Act:

While the Supreme Court itself did not explicitly detail the criteria for deeming JRCC "agency-like," the High Court decision it affirmed had pointed to factors such as the JRCC's establishment by a specific law, the contribution of state capital, the Minister of Transport's power to appoint and dismiss its officers, and the Minister's overall supervision, all leading to the conclusion that the JRCC was "part of the national administrative structure".

However, some scholars argue that such a purely organizational approach—looking at the general legal status of the entity—might lack the necessary clarity and precision for determining the nature of specific acts. An alternative or complementary approach, as suggested by Professor Hiroshi Shiono, would involve an analytical examination of the particular act in question (the Approval) by interpreting the empowering statute (the Shinkansen Act) to determine its specific legal properties.

Indeed, the Supreme Court's own investigating judge for this case offered an interpretation focusing on the Shinkansen Act's provisions. He noted that under the Act, the JRCC did not autonomously or voluntarily plan and execute Shinkansen construction. Instead, the Minister of Transport made the fundamental decision to build and issued instructions, and the JRCC was then responsible for the concrete construction work. This perspective frames the JRCC's role (including the creation of the works implementation plan) as essentially carrying out the Minister's prior decision, thereby reinforcing its "agency-like" character in this specific function.

3. The Internal vs. External Administrative Relationship Debate:

The judgment appears to treat a legal entity with administrative functions, like the JRCC, when interacting with the state, as an "organ" (kikan) subject to internal administrative processes, rather than as a "legal subject" (hōshutai) whose disputes with the state would be resolved by courts applying legal rules in an "external relationship". Despite the JRCC being a distinct legal personality separate from the state, the Court seemed to equate its role as an administrative entity with "agency-likeness," thereby classifying the relationship as internal for the purpose of this approval.

This approach has been debated. As a general proposition, it's not universally accepted that the relationship between an administrative legal entity (like a public corporation) and the state is always an internal one. The possession of a separate legal personality is typically a significant indicator of "legal subjecthood". Some influential scholars, including Professor Shiono, contend that when the legislature grants an entity independent legal personality, it generally signifies an acknowledgment of its status as a distinct legal subject. Consequently, disputes between such an entity and the state should, in principle, be considered legal disputes amenable to judicial resolution.

Illustrating a different facet of this issue, a 1994 Supreme Court decision concerning the National Finance Corporation (国民金融公庫 - Kokumin Kin'yū Kōko), another special public corporation, found that although the corporation served governmental administrative objectives, it was also an independent legal entity engaged in autonomous economic activities. The Court held that being a public corporation did not, by itself, prevent it from making claims against the state based on its own economic interests, particularly concerning its mandated lending activities. This suggests that the "internal vs. external" characterization can be nuanced and depends on the specific context and legal framework.

4. Alternative Perspectives on the Approval's Nature and the "Substance of the Dispute":

Interestingly, the first instance court in the JRCC case had stated that the Approval did grant the JRCC "the authority to implement the construction work based on the said plan". This language left open the possibility of interpreting the Approval as an administrative disposition directed towards the JRCC itself. If the Approval had been characterized this way—as an act that conferred specific rights or authorities upon the JRCC—then different legal questions might have come to the fore. These could include the standing of affected residents or local governments (like Edogawa Ward) to bring environmental lawsuits or to challenge the plan on other grounds, focusing on the potential harm caused by the JRCC's newly authorized activities.

Given that the actual interests at stake in this lawsuit were those of the local residents (concerning property rights and environmental interests) and the administrative interests of the local government (Edogawa Ward), rather than any internal interests of the JRCC, some commentators have suggested that an alternative theoretical construction—one that acknowledged the Approval's potential external effects via the JRCC's subsequent actions—might have better reflected the true substance of the conflict.

5. The Evolving Landscape: From JRCC to JRTT and Incorporated Administrative Agencies:

The commentary accompanying the judgment acknowledges that, at the time of the ruling (1978), positioning the JRCC as akin to an administrative organ was not entirely without rationale. The JRCC was specifically created to actively promote the construction of new railway lines, a function separated from the Japan National Railways (JNR), which then operated under a self-supporting accounting system. This establishment purpose suggested that the JRCC was intended to carry out public works projects on behalf of the government, free from the immediate profitability concerns that might constrain a purely commercial enterprise, thus fitting it somewhat into the national administrative framework.

However, the legal and administrative landscape in Japan has undergone significant changes since the 1970s. As part of broader administrative reforms, the JRCC was dissolved in 2003. Its functions were merged with those of the Corporation for Advanced Transport & Technology (運輸施設整備事業団) and transferred to a new entity: the Japan Railway Construction, Transport and Technology Agency (JRTT) (鉄道建設・運輸施設整備支援機構 - Tetsudō Kensetsu Un'yu Shisetsu Seibi Shien Kikō). Crucially, JRTT is structured as an "incorporated administrative agency" (独立行政法人 - dokuritsu gyōsei hōjin).

The incorporated administrative agency system represents a different model of public administration. It aims to separate policy planning functions (which generally remain with government ministries) from policy implementation functions. The latter are entrusted to these agencies, which are given independent legal personality and operate outside the direct hierarchical structure of national government organizations. The goals are to streamline the central government (vertical downsizing) and enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of public services. This model requires a careful delineation of the state's core tasks and a strict selection of functions that must be performed directly by national administrative organizations. (It is also noteworthy that current Shinkansen legislation allows the Minister of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism to instruct designated corporations other than JRTT to construct Shinkansen railways ).

These developments necessitate a re-evaluation of the 1978 judgment's contemporary significance. The legal nature of the relationship between the state and entities entrusted with administrative tasks, along with the broader theory of administrative legal personality, continues to evolve.

Conclusion: A High Bar for Challenging Approved Plans

The 1978 Supreme Court decision in the Narita Shinkansen case established a significant hurdle for citizens seeking to directly challenge ministerial approvals granted to special public corporations for large infrastructure projects. By characterizing the Japan Railway Construction Public Corporation as functionally subordinate to the Minister of Transport in this context, and the Minister's approval as an internal administrative act without direct external legal effect on citizens' rights, the Court effectively shielded such approvals from direct lawsuits by affected parties.

While the specifics of public corporation structures and administrative law have evolved in Japan, this case remains a key reference point for understanding the complexities of challenging governmental decisions involving specialized public entities and the distinction between internal administrative processes and externally reviewable administrative dispositions. It highlights the judiciary's traditional deference to the internal workings of the administration in the context of public works planning during that era, and the ongoing legal debate about how best to balance public project implementation with the protection of individual and community rights.