Japan Supreme Court on Medical‑Fee Reductions (1978): Why ‘Genten’ Isn’t an Administrative Disposition

TL;DR

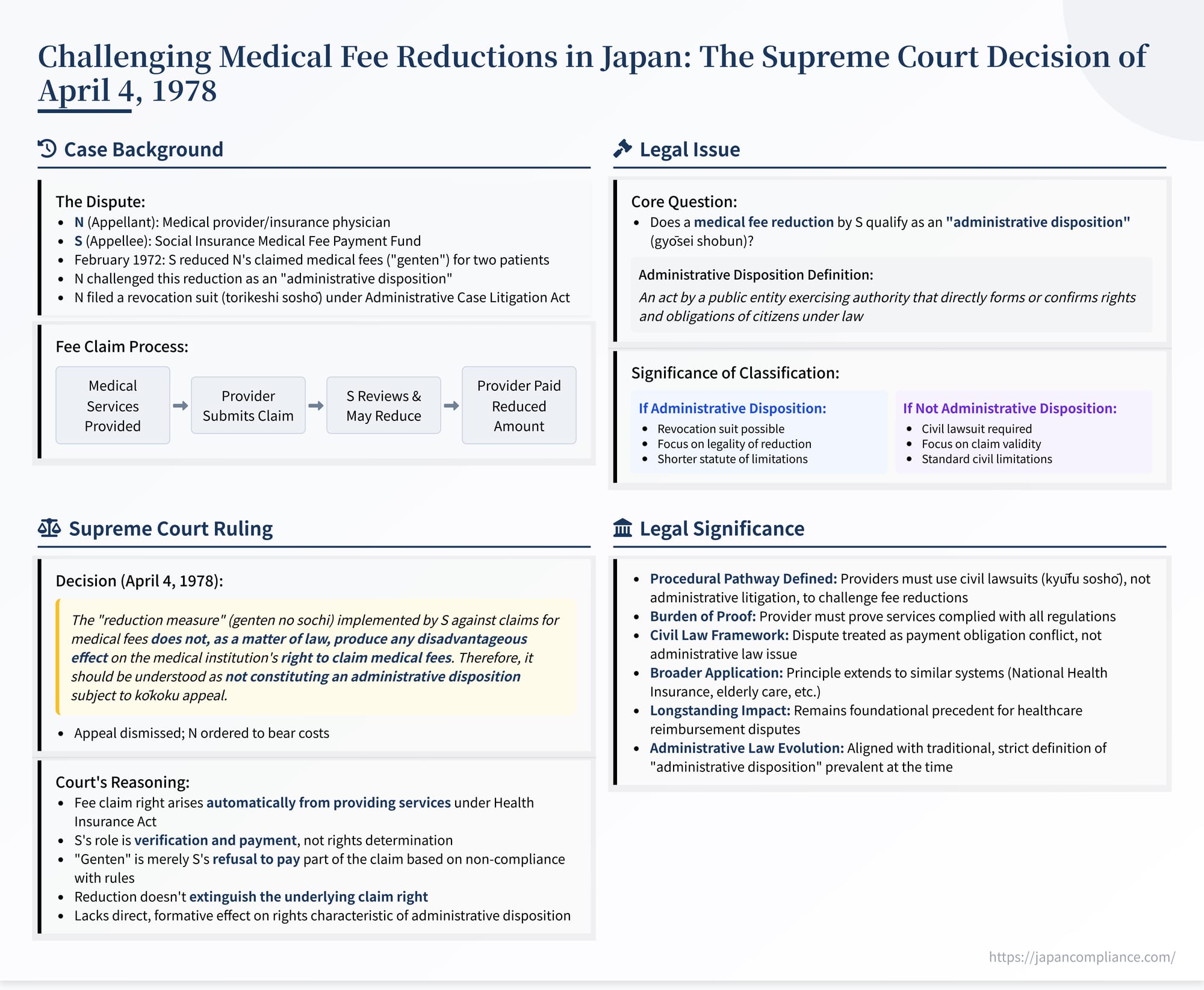

The 1978 Supreme Court clarified that fee “reductions” (genten) imposed by the Social Insurance Medical Fee Payment Fund are not administrative dispositions. Providers therefore must sue in ordinary civil court—rather than file an administrative revocation suit—to recover any amounts they believe were wrongly withheld.

Table of Contents

- Background: A Dispute Over Reduced Reimbursement

- Procedural History: Lower Courts Deny "Administrative Disposition" Status

- The Legal Question: What Constitutes an "Administrative Disposition"?

- Supreme Court's Ruling and Reasoning (April 4 1978)

- Elaboration and Implications of the Ruling

- Conclusion

On April 4, 1978, the Third Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan rendered a judgment in a case titled "Administrative Action Revocation Case" (1977 (Gyo-Tsu) No. 69). This decision addressed a critical procedural question within the Japanese healthcare system: Can a reduction in the amount of medical fees reimbursed to a healthcare provider by the designated review and payment body be considered an "administrative disposition" (行政処分 - gyōsei shobun)? The answer to this question determines the appropriate legal avenue for providers to challenge such reductions. The Supreme Court's concise ruling clarified that these reductions are not administrative dispositions, significantly shaping how disputes over medical billing are handled in Japan. This analysis delves into the case's background, the legal framework, and the implications of this judgment.

Background: A Dispute Over Reduced Reimbursement

The appellant, N, was the operator of an insurance medical institution and also an insurance physician under Japan's Health Insurance Act. The appellee, S (Social Insurance Medical Fee Payment Fund), was the entity entrusted by insurers (such as health insurance associations) with the administrative tasks of reviewing and paying claims for medical service fees (診療報酬 - shinryō hōshū) submitted by providers like N.

Around February 1972, S sent N a document titled "Monthly Points Increase/Decrease Notice." This notice informed N that S had decided to reduce (make a "genten" 減点) the points claimed, and thus the reimbursement amount, for services N had provided to two specific patients covered by insurance.

Believing this reduction was unjustified, N sought to challenge S's decision. N's legal strategy was predicated on the argument that S's act of reducing the claimed fee constituted an "administrative disposition." If correct, this classification would allow N to file a specific type of lawsuit under Japan's Administrative Case Litigation Act, known as a "revocation suit" (取消訴訟 - torikeshi soshō), directly challenging and seeking to nullify S's reduction decision. N accordingly filed such a suit.

Procedural History: Lower Courts Deny "Administrative Disposition" Status

The case progressed through the lower courts before reaching the Supreme Court.

First Instance (Gifu District Court): The District Court dismissed N's lawsuit. Its reasoning was that a provider's right to claim medical fees arises automatically based on laws and regulations whenever the provider performs a medical service covered by insurance. S's function, the court found, is to review whether the submitted claim conforms to these established standards. If S determines that a claim, or part of it, does not meet the standards, it implements a reduction ("genten") as a way of refusing payment for the non-compliant portion. This act of refusal, the court concluded, does not legally alter or affect the existence or scope of N's underlying right to claim fees; it is merely an expression of S's intent not to pay the full amount based on its review. As such, it did not constitute an "administrative disposition or other exercise of public authority" as defined in Article 3, Paragraph 2 of the Administrative Case Litigation Act, which is a prerequisite for filing a revocation suit.

Second Instance (Nagoya High Court): N appealed the dismissal, but the High Court affirmed the District Court's decision. The High Court reiterated that S's review process and the subsequent increase/decrease notification do not determine or finalize the amount of the medical fee claim right itself. Therefore, the reduction measure taken by S does not qualify as an administrative disposition. N's appeal was dismissed.

Undeterred, N appealed to the Supreme Court of Japan.

The Legal Question: What Constitutes an "Administrative Disposition"?

The crux of the appeal lay in the definition and scope of "administrative disposition" (gyōsei shobun) under Japanese administrative law. This concept is fundamental because the primary form of administrative litigation in Japan, the revocation suit (torikeshi soshō), can generally only be filed to challenge actions that qualify as administrative dispositions.

An administrative disposition is typically understood, based on established case law (e.g., Supreme Court judgment of October 29, 1964), as an act performed by the state or a public entity exercising public authority, which directly forms or confirms the rights and obligations of citizens under law. It is an official act with direct external legal effect on a specific individual's legal status or rights. Acts that are merely internal administrative processes, factual actions without direct legal consequences, or expressions of intent without binding legal force generally do not qualify.

The question before the Supreme Court was whether the "genten" measure – the act by S of reviewing a provider's claim and deciding to pay less than the amount requested based on non-compliance with rules – met this definition. Was it an exercise of public authority that directly and legally impacted N's rights, or was it something else?

Supreme Court's Ruling and Reasoning (April 4, 1978)

The Supreme Court delivered its judgment on April 4, 1978. The outcome was the dismissal of N's appeal.

The Court's reasoning was remarkably brief, stating essentially:

"The so-called 'reduction measure' (genten no sochi) implemented by the Appellee, Social Insurance Medical Fee Payment Fund, against claims for medical fees from insurance medical institutions does not, as a matter of law, produce any disadvantageous effect on the insurance medical institution's right to claim medical fees or its other rights and obligations. Therefore, it should be understood as not constituting an administrative disposition subject to kōkoku appeal [a category including revocation suits]."

The Court concluded that the judgment of the lower court (the Nagoya High Court) holding the same view was correct and that there was no legal error in the original judgment. N's arguments were thus rejected. The appeal was dismissed, and N was ordered to bear the costs of the appeal.

Elaboration and Implications of the Ruling

While the Supreme Court's text is concise, its alignment with the lower courts' reasoning and subsequent commentary provide a clearer understanding of the underlying rationale and the decision's significant implications.

Rationale Revisited:

- Nature of the Fee Claim Right: The courts operate on the premise that the right of an insurance medical institution to claim fees arises directly from providing medical services in accordance with the Health Insurance Act and associated regulations (like the Rules for Insurance Medical Care Organs and Doctors in Charge of Insurance Medical Care - 療養担当規則, Ryōyō Tantō Kisoku). This right exists independently of S's review.

- Role of the Payment Fund (S): S's role, delegated by insurers, is primarily one of verification and payment. It examines the submitted claims against the established rules (covering medical necessity, adherence to standards of care, correct coding, etc.).

- Reduction as Refusal of Performance: The "genten" or reduction is interpreted not as an act that legally diminishes or alters N's pre-existing claim right, but rather as S's determination that a portion of the claim does not meet the regulatory requirements for payment. It is, in essence, a statement of non-liability for that specific part of the claim and a refusal to perform the payment obligation for that part. It's akin to a debtor asserting that a claimed amount is not actually due under the terms of an agreement or governing rules.

- Lack of Direct Legal Effect on Rights: Because the reduction itself doesn't extinguish N's underlying legal claim (if N believes the full amount is compliant with the rules), it lacks the direct, formative effect on rights and obligations characteristic of an administrative disposition. N remains free to assert the validity of the full claim through other legal means.

Consistency with Administrative Law Principles: This interpretation aligns with the traditional, relatively strict definition of "administrative disposition" prevalent at the time. While Japanese administrative law has seen some evolution towards broader interpretations of what constitutes a reviewable administrative act, particularly after amendments to the Administrative Case Litigation Act in 2004, the core principle applied here – that an act must directly alter legal rights to be a disposition – remains a key consideration. The judgment contrasts with situations where a statute explicitly grants an administrative body the power to determine the amount payable (as seen in some social welfare contexts, like medical aid under the Public Assistance Act, where decisions on fee amounts have been found to be administrative dispositions). The Health Insurance Act, at the time and arguably still, framed the payment process more as verification and payment of claims arising under regulations, rather than a formal determination of rights by S.

Practical Consequences for Providers:

- No Revocation Suit: The most significant practical implication is that healthcare providers cannot use the administrative revocation suit (torikeshi soshō) to challenge fee reductions made by S (or similar bodies like the National Health Insurance Organization Federations, which were later subject to a similar Supreme Court ruling). Revocation suits often have advantages, such as potentially shorter statutes of limitations (though sometimes stricter) and procedures focused specifically on the legality of the administrative act itself.

- Civil Lawsuit Required: Instead of administrative litigation, providers who disagree with a fee reduction must pursue their claim through ordinary civil litigation. They need to file an "action for performance" (給付訴訟 - kyūfu soshō) against S, demanding payment of the unpaid (reduced) amount.

- Burden of Proof: In such a civil suit, the provider (plaintiff) bears the burden of proving that the medical services rendered fully complied with all relevant regulations and guidelines, and therefore, the full claimed amount is legally due. The dispute shifts from reviewing the legality of S's "reduction act" to proving the substantive validity of the original fee claim itself under the governing healthcare rules within the framework of a civil trial.

- Statute of Limitations: The standard civil statute of limitations for claims (which has changed over time but is generally longer than the typical period for administrative revocation suits) would apply.

Scope and Enduring Relevance: This ruling's principle extends beyond the Health Insurance Act to other similar systems in Japan where review/payment bodies handle claims based on fee schedules and regulations, such as National Health Insurance, healthcare for the elderly, and potentially Long-Term Care Insurance (介護保険 - Kaigo Hoken) and services under the Comprehensive Support for Persons with Disabilities Act (障害者総合支援法 - Shōgaisha Sōgō Shien Hō), where similar payment mechanisms involving delegated review exist. While administrative law evolves, this 1978 decision remains a foundational precedent establishing that routine payment adjustments based on regulatory compliance review within Japan's social insurance systems are generally treated as matters of payment obligation fulfillment (or refusal) subject to civil, not administrative, judicial review.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's decision on April 4, 1978, firmly established that the reduction of medical fee claims by the Social Insurance Medical Fee Payment Fund (S) does not constitute an "administrative disposition" under Japanese law. By classifying these reductions as essentially a refusal to pay a portion of a claimed debt based on non-compliance with rules, rather than an act directly altering the provider's legal rights, the Court mandated that disputes over such reductions must be resolved through standard civil lawsuits seeking payment, not through administrative revocation actions. This procedural clarification has had a lasting impact, defining the legal pathway for healthcare providers in Japan seeking to challenge reimbursement decisions made by intermediary payment organizations.

- Japan Supreme Court 2023 Pension‑Cut Ruling: Balancing Sustainability and Recipient Rights

- Japan’s Supreme Court Upholds Compulsory National Health Insurance (1958)

- Japan Supreme Court 2017 Survivor‑Pension Case: Why Age Rules for Widowers Survived an Equality Challenge

- 審査支払機能の在り方に関する検討会(第1回)議事録 – 厚生労働省

- レセプト振替・分割に係る概要(PDF) – 厚生労働省