Challenging "Guidance": Japan's Supreme Court on the Reviewability of Hospital Opening Recommendations (2005)

TL;DR

Japan’s Supreme Court held in 2005 that a seemingly non‑binding recommendation under the Medical Care Act becomes a reviewable “administrative disposition” when it predictably leads to denial of national health‑insurance designation, effectively blocking a new hospital from operating.

Table of Contents

- Background: Health Planning, Recommendations, and Insurance Designation

- The Facts of the Case: Recommendation Ignored, Permit Granted, Warning Issued

- The Legal Challenge: Seeking Review of the Recommendation and Warning

- The Supreme Court’s Decision: Recommendation Found Reviewable

- Significance and Analysis

- Conclusion

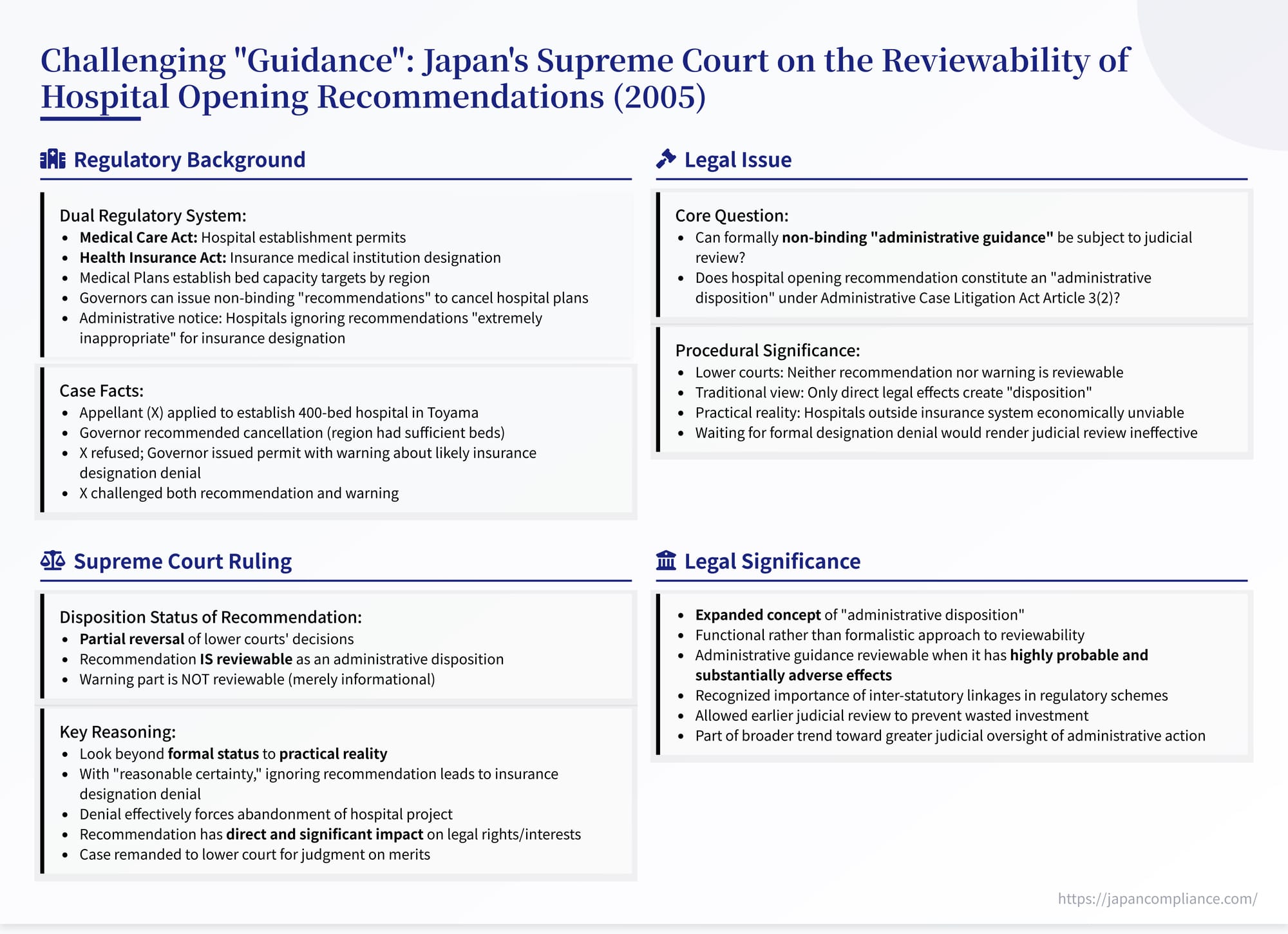

Administrative agencies often use various tools beyond formal permits or denials to influence private activity, including issuing guidance or non-binding recommendations. A crucial question in administrative law is when such "soft law" instruments cross the line and become subject to judicial review as formal "administrative dispositions" that directly affect legal rights. If guidance, while technically non-binding under one statute, carries predictable and severe negative consequences under another related regulatory regime, can it be challenged in court? Japan's Supreme Court addressed this complex issue in a significant 2005 decision involving a recommendation issued under the Medical Care Act advising against the opening of a new hospital due to regional bed surplus. This case, formally the Case Concerning Request for Revocation of Recommendation, etc. (Supreme Court, Second Petty Bench, Heisei 14 (Gyo-Hi) No. 207, July 15, 2005), expanded the scope of judicially reviewable administrative actions by looking beyond the formal label of the guidance to its practical impact within the interconnected healthcare regulatory system.

Background: Health Planning, Recommendations, and Insurance Designation

Japan operates a dual system for regulating the establishment and operation of hospitals. First, under the Medical Care Act (医療法, Iryō Hō), anyone wishing to open a hospital must obtain a permit from the prefectural governor. The criteria for this permit historically focused primarily on ensuring the facility meets required standards for staffing, equipment, and structure to guarantee patient safety.

Second, the Medical Care Act also mandates that prefectures establish Medical Plans (医療計画, iryō keikaku). These plans are designed to promote the rational allocation of healthcare resources and the efficient provision of quality care. A key component involves dividing the prefecture into healthcare regions and establishing target numbers for necessary hospital beds within each region based on population needs. To help achieve these planning goals, Article 30-7 of the Medical Care Act (at the time) empowered the prefectural governor, after consulting with the prefectural medical council, to issue a recommendation (kankoku) to entities applying to open a new hospital or increase bed capacity, advising them to cancel or modify their plans if deemed necessary to promote the Medical Plan (e.g., if the region already had sufficient or excess beds). Importantly, the Medical Care Act itself stipulated no direct legal penalty or disadvantage for disregarding such a recommendation; it was formally positioned as non-binding administrative guidance (gyōsei shidō).

However, a separate regulatory layer exists under the Health Insurance Act (健康保険法, Kenkō Hoken Hō). For a hospital to treat patients under Japan's universal public health insurance system (which covers the vast majority of the population) and receive reimbursement, it must obtain designation as an Insurance Medical Institution (保険医療機関, hoken iryō kikan) from the relevant authority (at the time, typically the prefectural governor acting under delegation from the national government). Without this designation, operating a hospital is generally not economically viable. The Health Insurance Act (Art. 43-3(2) in the pre-1998 version relevant here) allowed the designating authority to refuse designation on several grounds, including a catch-all clause if the facility was deemed "otherwise... extremely inappropriate" (其ノ他…著シク不適当ト認ムルモノナルトキ).

Crucially, long-standing administrative practice, formalized by a 1987 notice from the Ministry of Health and Welfare's Insurance Bureau Director (昭和62年保険局長通知, Shōwa 62nen Hoken-kyokuchō Tsūchi), explicitly linked the Medical Care Act's recommendation system to the Health Insurance Act's designation process. This notice guided designating authorities to consider a hospital opened despite receiving a cancellation recommendation under MCA Art. 30-7 as falling under the "extremely inappropriate" category for HIA designation purposes, and to consult the regional social insurance medical council regarding denial on these grounds.

The Facts of the Case: Recommendation Ignored, Permit Granted, Warning Issued

The appellant, X, planned to establish a large, 400-bed hospital in Takaoka City, Toyama Prefecture. X duly applied to the Governor of Toyama Prefecture (Y, the appellee/defendant) for the necessary establishment permit under the Medical Care Act in March 1997.

In October 1997, the Governor (Y) issued a formal recommendation (本件勧告, honken kankoku) to X under MCA Article 30-7, advising X to cancel the hospital opening. The stated reason was that the number of existing hospital beds in the Takaoka healthcare region already met the target set in the prefectural Medical Plan.

X promptly notified the Governor of the intent to refuse the recommendation and demanded issuance of the establishment permit. Since non-compliance with the recommendation was not, under the Medical Care Act itself, grounds for denying the permit, the Governor granted the hospital establishment permit in December 1997 (本件許可処分, honken kyoka shobun).

However, on the very same day the permit was issued, the Director of the Prefectural Health Department (acting on behalf of the Governor) sent X a separate document. This document included standard clauses urging compliance with the Medical Care Act and cooperation with the Medical Plan, but it also contained a specific warning (referred to as 本件通告部分, honken tsūkoku bubun): "Furthermore, please be advised that, according to Ministry of Health and Welfare notices (specifically, the 1987 Insurance Bureau Director Notice...), in cases where a hospital is opened despite a cancellation recommendation, designation as an Insurance Medical Institution is to be refused." This effectively put X on notice that proceeding with the opening, while legally permitted under the MCA, would likely result in being barred from participating in the essential public health insurance system.

The Legal Challenge: Seeking Review of the Recommendation and Warning

X filed suit against the Governor (Y), seeking the revocation (torikeshi) of both:

- The initial recommendation to cancel the opening, arguing it was illegally issued under MCA Art. 30-7 (presumably challenging the assessment of need or the basis for the recommendation).

- The warning part (tsūkoku bubun) included with the permit, arguing this effectively turned the permit into a conditional one, illegally burdening X's right to operate.

The lower courts (Toyama District Court and Nagoya High Court, Kanazawa Branch) dismissed X's entire lawsuit, finding that neither the recommendation nor the warning part constituted an "administrative disposition" (shobun) – defined under Article 3(2) of the Administrative Case Litigation Act (ACLA) as an "act of an administrative agency or other exercise of public authority" – that could be subject to judicial review via a revocation lawsuit (torikeshi soshō). They viewed the recommendation as mere non-binding administrative guidance and the warning as simply conveying information about potential future consequences, neither directly altering X's legal rights or obligations at that stage. X appealed this dismissal to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Recommendation Found Reviewable

The Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court partially reversed the lower courts. While it agreed that the warning part (tsūkoku bubun) was not itself a reviewable disposition, it crucially held that the initial hospital opening cancellation recommendation (honken kankoku) under MCA Article 30-7 does constitute an administrative disposition subject to judicial review under ACLA Article 3(2).

Consequently, the Court:

- Upheld the dismissal of the lawsuit concerning the warning part.

- Overturned the dismissal of the lawsuit concerning the recommendation.

- Vacated the first-instance (District Court) judgment regarding the recommendation part.

- Remanded that part of the case back to the Toyama District Court for a trial on the merits (i.e., to determine whether the recommendation itself was legally valid).

Reasoning on the Disposition Status of the Recommendation:

The Court's reasoning for finding the formally non-binding recommendation reviewable is the most significant aspect of the judgment:

- Formal Status vs. Practical Reality: The Court acknowledged that under the Medical Care Act alone, the recommendation is framed as administrative guidance, which the recipient is legally free to ignore without direct penalty under that Act.

- Interconnected Regulatory System: However, the Court looked beyond the MCA in isolation and considered the practical operation and interconnection between the MCA's planning/recommendation system and the Health Insurance Act's designation system, particularly as implemented through the 1987 administrative notice.

- Predictable Consequence: This interconnectedness meant that receiving an MCA cancellation recommendation created a situation where, with "reasonable certainty" (sōtō teido no kakujitsu-sa), disregarding the recommendation would lead to the denial of HIA designation. The administrative notice essentially pre-determined the outcome of the designation application based on compliance with the earlier recommendation.

- Severity of Non-Designation: The Court then emphasized the drastic practical consequences of being denied HIA designation. Citing the reality of Japan's universal health insurance system as "public knowledge," it stated that hospitals operating outside the insurance system are virtually non-existent. Therefore, denial of designation effectively forces the applicant to "abandon the hospital opening itself."

- Combined Effect = Disposition: Considering the combined effect – the recommendation's predictable impact on the essential HIA designation, and the critical importance of that designation for the hospital's very existence – the Court concluded that the recommendation itself directly and significantly impacts the recipient's legal rights and interests related to opening and operating a hospital. This impact is sufficiently direct and legally relevant to qualify the recommendation as an "administrative disposition or other exercise of public authority" under ACLA Article 3(2), despite its formal label as non-binding guidance under the MCA.

- Irrelevance of Later Challenge Opportunity: The Court explicitly rejected the argument that the ability to later challenge the actual designation denial (if and when it occurred) precluded review of the recommendation itself. Given the enormous financial investment required to build and equip a hospital before applying for designation, forcing applicants to wait for a near-certain denial risked rendering any subsequent judicial review meaningless, as the project would likely be abandoned due to the initial negative signal from the recommendation. Early review of the recommendation was necessary for effective relief.

Thus, the Court significantly broadened the scope of reviewable administrative actions, allowing a challenge to formally non-binding guidance based on its predictable and severe consequences within a linked regulatory framework.

(Outcome on Remand): As noted in commentary, when the case went back to the lower courts, they ultimately found the Governor's handling of X's application involved procedural flaws (violating the Administrative Procedure Act) leading up to the recommendation, and consequently revoked the recommendation itself.

Significance and Analysis

The 2005 Supreme Court decision on the reviewability of hospital opening cancellation recommendations is a landmark ruling in Japanese administrative law with important implications:

- Expanding the Concept of "Administrative Disposition": This case is a key example of the trend in Japanese courts since the early 2000s to adopt a more flexible and functional approach to determining what constitutes a reviewable "disposition" under the ACLA. It moved beyond the traditional, more rigid definition requiring a direct formation or confirmation of legal rights/duties based solely on the act itself, and instead considered the act's practical impact and predictable consequences within the broader regulatory landscape.

- Judicial Review of Administrative Guidance: It established that formally non-binding administrative guidance (gyōsei shidō), like a recommendation, can be subject to judicial review as a disposition if it is shown to have a highly probable and substantially adverse effect on the recipient's rights or legal interests, particularly due to established administrative practices or linkages with other regulatory decisions (like licensing or designation).

- Importance of Inter-statutory Linkages: The decision underscores the importance of analyzing how different laws and administrative practices interact. The recommendation under the MCA gained its dispositive character primarily because of its well-established linkage (via administrative notice) to the designation decision under the HIA.

- Need for Early Judicial Review: The Court recognized the potential inadequacy of remedies if review is only available at a much later stage (after designation denial), especially when significant investment and planning are involved. By allowing review of the recommendation, it provided an avenue for earlier legal certainty, potentially preventing wasted investment based on potentially unlawful guidance.

- Potential Scope and Limitations: While significant, the scope of this ruling might be context-dependent. Key factors included the high certainty of the negative consequence (designation denial) following non-compliance and the extreme severity of that consequence (effective impossibility of operating the hospital). Whether less certain or less severe consequences flowing from other forms of administrative guidance would trigger review remains an open question. Some legal scholars expressed concern that broadly treating guidance as a disposition could lead to unintended consequences related to legal doctrines like finality and statutes of limitation, though others argue these can be managed through careful application of legal principles like standing and ripeness, or by allowing different forms of legal action.

- Subsequent Legislative Changes: Notably, the specific linkage between MCA recommendations and HIA designation was later codified more explicitly in the Health Insurance Act itself (in a 1998 amendment mentioned by the Court), potentially reducing the need for this type of judicial interpretation regarding this specific connection in later years. However, the principle established by the case – looking at practical effects to determine disposition status – remains relevant for other forms of administrative guidance.

Conclusion

The 2005 Supreme Court judgment marked a significant development in Japanese administrative law by recognizing that a formally non-binding recommendation issued under the Medical Care Act could constitute a judicially reviewable administrative disposition. This conclusion was reached not by examining the recommendation in isolation, but by analyzing its practical and highly predictable adverse consequences within the interconnected system of healthcare regulation, particularly its near-certain impact on the essential health insurance designation required for a hospital's viability. The decision represents a move towards a more functional understanding of "disposition," allowing for earlier judicial review of administrative actions that, while labeled as guidance, effectively determine the fate of significant private undertakings due to their linkage with subsequent regulatory decisions.

- Sustainable Pensions vs. Recipient Rights: Japan’s Supreme Court Addresses Pension Cuts (2023)

- When a Lie Becomes a Crime: Japan’s Landmark Case on Lying for an Arrested Friend

- The Scapegoat Gambit: A Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Aiding an Arrested Criminal’s Escape

- National Health‑Insurance System — MHLW