Challenging a Father's Name After Death: Japan's Supreme Court on Belated Paternity Invalidation Claims

Judgment Date: April 6, 1989 (Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench)

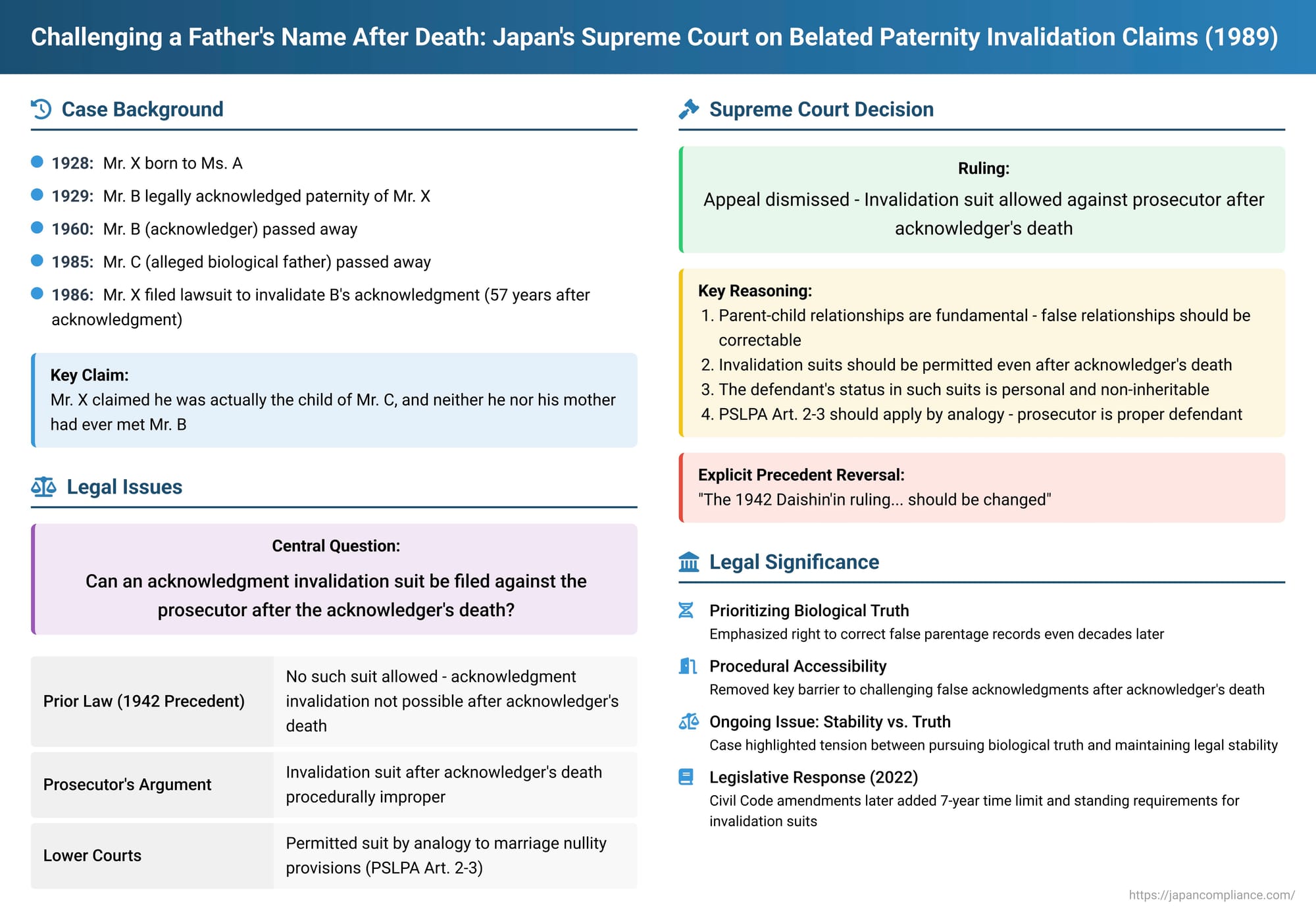

In a significant 1989 decision, the Supreme Court of Japan addressed a complex and long-debated issue: can an individual, decades after a legal acknowledgment of paternity was made and long after the acknowledger has died, still bring a lawsuit to invalidate that acknowledgment by suing the public prosecutor? The Court's affirmative answer in this "Claim for Invalidation of Acknowledgment, etc." case marked a pivotal shift in Japanese family law, prioritizing the pursuit of biological truth in parentage matters over strict procedural impediments and overturning a nearly 50-year-old precedent.

A Decades-Old Acknowledgment and a Quest for Truth: The Facts

The case concerned Mr. X, the plaintiff. He was officially registered as having been born to his mother, Ms. A, on January 16, 1928. Subsequently, on April 19, 1929, a legal acknowledgment of paternity by a Mr. B was registered for Mr. X. Mr. B, the acknowledger, passed away in 1960.

Many years later, around 1986—approximately 57 years after the acknowledgment and 26 years after Mr. B's death—Mr. X filed a lawsuit to have Mr. B's acknowledgment declared invalid. He named the public prosecutor, Y, as the defendant, which is a common procedural path in certain types of status litigation when a direct party is deceased. Mr. X's central claim was that he was actually the child of his mother, Ms. A, and another man, Mr. C, and that neither he nor his mother had ever even met Mr. B. Mr. C had reportedly died in 1985. Complicating matters, Mr. X had also initiated a separate suit seeking posthumous acknowledgment from Mr. C (also against the prosecutor), which was initially joined with the invalidation suit against Mr. B's acknowledgment but later separated. It appears that Mr. C's own child and grandchild participated in the invalidation suit as auxiliary intervenors supporting the defendant prosecutor.

The Legal Hurdles: Can Such a Late Claim Even Be Heard?

The public prosecutor, Y, argued that a lawsuit to invalidate an acknowledgment, filed against the prosecutor after the death of the acknowledger, was procedurally improper and should not be allowed.

However, the lower courts found in favor of Mr. X:

- The first instance court permitted the lawsuit, applying by analogy Article 2, Paragraph 3 of the old Personal Status Litigation Procedure Act (PSLPA of Meiji 31, Law No. 13), which allowed for the prosecutor to be sued in certain marriage-related cases if a spouse was deceased. On the merits of the case, the court found that Ms. A's actual partner was not Mr. B and thus granted Mr. X's claim to invalidate the acknowledgment.

- The appellate court dismissed the prosecutor's appeal, upholding the first instance court's decision.

The prosecutor then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision: Overturning Precedent to Allow the Suit

The Supreme Court dismissed the prosecutor's appeal, thereby affirming the lower courts' decisions and allowing Mr. X's suit to proceed against the prosecutor. This ruling was significant because it directly overturned a 1942 Daishin'in (pre-WWII Supreme Court) precedent that had barred such suits.

The Supreme Court's reasoning was as follows:

- Fundamental Nature of Parent-Child Relationships: Parent-child relationships are the bedrock of family status. If an acknowledged paternity is contrary to the biological truth, the acknowledged person (in this case, Mr. X) has a legitimate legal interest in having that false relationship declared non-existent. This is crucial for resolving current legal disputes that arise from the effects of the incorrect acknowledgment.

- Appropriateness of Post-Mortem Suits: Given this legal interest, it is appropriate to permit a suit to invalidate an acknowledgment even after the death of the person who made the acknowledgment.

- Defendant's Status is Personal: The role of the defendant in an acknowledgment invalidation suit (i.e., the acknowledger) is personal to that individual and is not a status that can be inherited by their heirs. This is analogous to the defendant's role in suits for the nullity or annulment of a marriage.

- Analogous Application of Procedural Law for Prosecutors as Defendants: Because the defendant's role is personal and non-inheritable, when the acknowledger dies, a procedural mechanism is needed to allow the suit to proceed. Therefore, Article 2, Paragraph 3 of the old PSLPA—which provided for the public prosecutor to be the defendant in marriage nullity or annulment suits if a spouse was deceased—should be applied by analogy to acknowledgment invalidation suits. This means that if the acknowledger has died, the public prosecutor should be named as the defendant.

- Overturning Precedent: The Court explicitly stated that its interpretation differed from the 1942 Daishin'in ruling (Daishin'in, January 17, 1942, Minshu Vol. 21, No. 1, p. 14), and that the old precedent "should be changed".

The Significance: Why This Ruling Mattered

This 1989 Supreme Court decision was a critical development in Japanese family law for several reasons:

- It resolved a long-standing procedural ambiguity under the old Personal Status Litigation Procedure Act regarding who, if anyone, could be sued to invalidate an acknowledgment after the acknowledger's death.

- The ruling aligned the Supreme Court's stance with the prevailing academic opinion and the evolving practice in lower courts and family register procedures, which had already begun to allow such suits against the prosecutor.

- Most importantly, it signaled a judicial emphasis on the importance of biological truth in parentage matters, allowing individuals to correct the legal record even decades later, rather than being indefinitely bound by a false acknowledgment due to procedural hurdles.

Historical Context: Evolving Views on Posthumous Challenges to Parentage

The path to the 1989 decision was paved by a gradual evolution in legal thought and practice:

- Restrictive Past: Early Daishin'in precedents had generally held that if the necessary party (the acknowledger, or both the acknowledger and the acknowledged person in suits by third parties) had died, an invalidation suit could not be brought against the prosecutor. The 1942 Daishin'in case, specifically overturned by the 1989 ruling, argued that the truth of the blood relationship could only be properly investigated with the acknowledger as a party.

- Influence of 1942 Reforms: A significant turning point was the 1942 revision of the Civil Code and the old PSLPA, which, among other things, allowed children to file suits for posthumous acknowledgment of paternity against the public prosecutor after the alleged father's death. This development led many legal scholars to argue that, by analogy, suits to invalidate an acknowledgment should also be permissible against the prosecutor after the acknowledger's death.

- Parallel Developments: A similar shift occurred in cases concerning the confirmation of parent-child relationships where no acknowledgment had ever been made. Initially restrictive, the Supreme Court eventually permitted such suits against the prosecutor when a party was deceased.

The 1989 decision was thus a culmination of these trends, reflecting a broader movement within Japanese family law.

The Rationale for Allowing Post-Mortem Invalidation Suits

Several substantive reasons supported the Supreme Court's 1989 decision:

- Preventing Injustice: If suits to invalidate an acknowledgment were purely "formative" (i.e., they create a new legal status of non-parentage), then disallowing them after the acknowledger's death could lead to significant injustice. An individual might be permanently bound by a false paternity, potentially blocking their ability to establish their true parentage (as Mr. X sought to do with Mr. C). It would also render testamentary acknowledgments (acknowledgments made in a will) entirely unchallengeable after the acknowledger's death.

- Legal Interest in Accuracy: Even if such suits are viewed as "declaratory" (confirming an existing state of invalidity due to lack of biological connection), the acknowledged person has a clear legal interest in correcting a false public record of their parentage.

- Shift Towards Fact-Based Parentage: The decision reflected a broader trend in Japanese acknowledgment law away from "intent-based" theories (where the act of acknowledgment itself was paramount) towards a "fact-based" or "blood-tie" approach, where the underlying biological reality is given greater weight.

- Addressing Concerns about Truth-Finding: The old Daishin'in's concern that truth could not be found without the acknowledger was largely mitigated by the fact that other types of posthumous parentage suits (e.g., suits against the acknowledged child if the acknowledger died, suits to establish paternity against the prosecutor, posthumous acknowledgment suits by children) were already permitted, indicating that courts were equipped to handle evidence in such situations.

The Question of Time Limits and Legal Stability

Mr. X's lawsuit was filed an exceptionally long time after the acknowledgment and the acknowledger's death, raising concerns about legal stability, which were voiced by the auxiliary intervenors through arguments of laches or abuse of rights.

- No Specific Time Limit for Invalidation (at the time): A key point is that, at the time of the 1989 ruling, the Japanese Civil Code did not prescribe a specific time limit for bringing a suit to invalidate an acknowledgment. This was in contrast to suits for posthumous acknowledgment by a child, which had (and still have) a three-year limitation period from the father's death (Civil Code Art. 787 proviso). The Supreme Court, by allowing Mr. X's suit, implicitly decided that this three-year limit did not apply by analogy to invalidation claims. The rationale for the three-year limit in acknowledgment claims (difficulty in gathering evidence over time, risk of fraudulent claims, and the need for stability in family relations) could arguably apply to invalidation claims as well.

- Tension Between Truth and Stability: Allowing challenges to long-standing family statuses, particularly when inheritance rights are affected, can create significant legal instability. While a suit by the acknowledged person themselves (like Mr. X) might raise fewer such concerns compared to suits by third parties aiming to dislodge an heir, the potential for disruption is always present. Even without fixed time limits, the doctrine of "abuse of rights" could be invoked as a judicial check on extremely delayed or vexatious claims. The Supreme Court had previously recognized the possibility of abuse of rights in suits for the confirmation of non-existence of parent-child relationships, and a later 2014 Supreme Court decision, which allowed an acknowledger to sue to invalidate his own non-biological acknowledgment, also mentioned abuse of rights as a potential constraint.

Legislative Update: The 2022 Civil Code Amendments – New Rules for Stability

While the 1989 Supreme Court decision clarified that suits for invalidating an acknowledgment could be brought against the prosecutor after the acknowledger's death, and the current Personal Status Litigation Act (PSLA of Heisei 15, Law No. 109) codified the prosecutor's defendant standing in such general terms, further legislative changes in 2022 specifically addressed the who and when of these invalidation suits.

The "Act to Partially Amend the Civil Code, etc." (Law No. 102 of Reiwa 4, effective 2022), driven by a desire to enhance the stability of family relationships affected by acknowledgments, introduced significant reforms:

- Defined Standing: The amendment specifies who can file a suit to invalidate an acknowledgment. As a general rule, this includes the child, the child's legal representative, the acknowledger, and the child's mother.

- Statutory Time Limits: Crucially, the amendment establishes time limits for bringing such suits. Generally, the action must be brought within seven years from the time of the acknowledgment or from when the party learned of the acknowledgment. For a child plaintiff, this period extends until they reach the age of 21.

- Restrictions Based on Child's Interests: The law also incorporates provisions that allow for the restriction of invalidation claims based on considerations such as the child's best interests.

These 2022 amendments aim to strike a more explicit balance between the possibility of correcting false acknowledgments and the need for legal certainty and stability in family relationships. While a suit against the prosecutor after the acknowledger's death, as permitted by the 1989 ruling, remains theoretically possible, its practical scope is now considerably narrowed by these new rules on standing and time limits. The general principle of abuse of rights may also continue to play a role in exceptional cases.

Conclusion: Prioritizing Truth, Evolving Towards Stability

The Supreme Court's 1989 decision was a landmark in Japanese family law, empowering individuals to challenge false acknowledgments of paternity even long after the acknowledger's death by establishing the public prosecutor as a proper defendant. This ruling underscored a judicial commitment to ensuring that legal parentage aligns with biological reality, even if it meant overturning long-standing precedents.

While this foundational decision opened the door for truth-seeking, the subsequent 2022 amendments to the Civil Code have refined the process, introducing specific rules on who can bring such challenges and imposing time limits. This legislative evolution reflects an ongoing effort to balance the fundamental right to an accurate legal identity with the societal need for stability and predictability in family relationships. The 1989 judgment remains a testament to the law's capacity to adapt, while the newer legislation seeks to channel that adaptability within a framework that also safeguards established ties.