Causation, Negligence, and "Induced" Acts: A Deep Dive into a Landmark Japanese Supreme Court Decision

Decision Date: December 17, 1992

Case Number: 1992 (A) No. 383

Case Name: Professional Negligence Resulting in Death

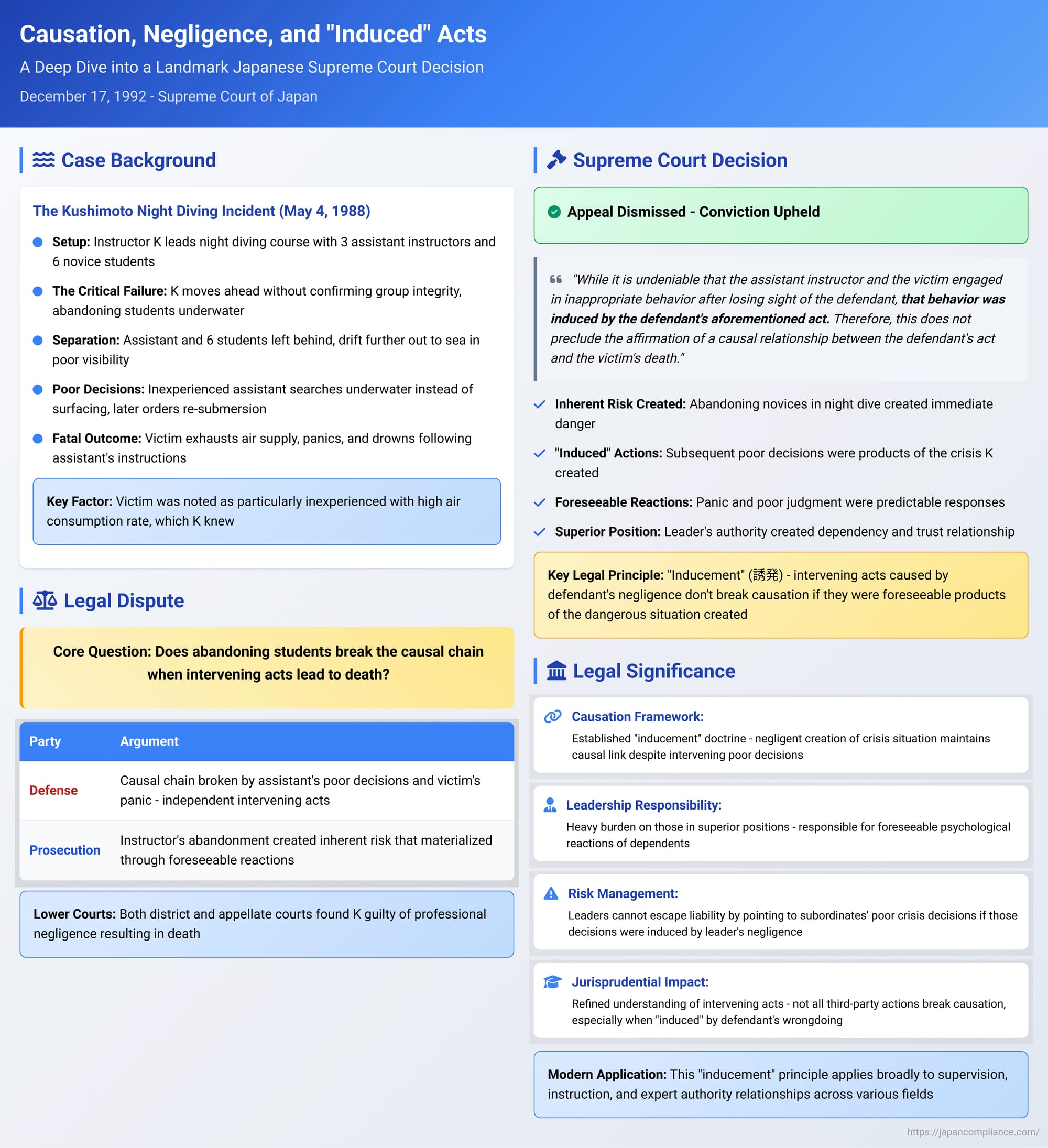

In the intricate world of negligence law, the concept of causation—the link between a negligent act and the resulting harm—is often a battlefield of legal argument. How far does responsibility extend? What happens when another person's actions, or even the victim's own choices, intervene between the initial negligence and the final, tragic outcome? A pivotal 1992 decision by the Supreme Court of Japan delves into this very question, offering a profound analysis of responsibility in high-stakes environments. The case, involving a fatal scuba diving incident, introduces a crucial concept: that of an intervening act being "induced" by the defendant's initial failure, thereby keeping the chain of causation intact.

This case provides a compelling study for anyone involved in managing risk, overseeing operations, or providing expert guidance. It illustrates how Japanese jurisprudence assigns a heavy burden of care to those in positions of superior knowledge and authority, especially when they lead others into inherently dangerous situations.

The Factual Background: A Night Dive Gone Wrong

The case centered on the actions of K, a certified scuba diving instructor. The incident took place on the evening of May 4, 1988, during a night diving course conducted in the coastal waters of Kushimoto, Wakayama Prefecture.

The Participants and Conditions:

- The Instructor (Defendant K): A certified instructor leading the course.

- The Assistant Instructors: Three assistants, who held advanced diver certifications but were participating in the course to gain a higher-level qualification. They had very limited experience as instructors, especially in night diving.

- The Students: A group of six students, including the victim. While they held a basic certification from a recognized organization, they were still considered novices.

- The Victim: Noted as being particularly inexperienced among the students, with limited dive history and no prior experience with night diving. The defendant, K, was aware that the victim consumed air at a higher rate than the other students.

- The Environment: The dive occurred at night. Visibility was poor due to the time of day and recent rainfall. A consistent wind of about 4 meters per second was present on the surface.

The Sequence of Events:

The course began with K leading the entire group—three assistants and six students—underwater. K had assigned one assistant instructor to supervise every two students. After advancing about 100 meters, K stopped to catch a fish to show the students.

It was at this moment that the critical failure occurred.

K decided to resume the dive, moving forward under the assumption that the entire group would simply follow him. He gave no specific instructions to his assistants and, crucially, failed to look back to confirm that the group was intact. After proceeding some distance, he turned around to discover that only two of his three assistants were behind him. The rest of the group was gone.

Unbeknownst to K, the remaining assistant instructor and all six students had been distracted by the fish K had caught. They failed to notice his departure and were left behind. Compounding the problem, an ocean swell began to push the separated group further out to sea.

In the confusion, this lone assistant instructor, tasked with supervising students but now without his lead instructor, made a fateful decision. Instead of surfacing as general safety protocols for separation would suggest, he began moving further out to sea, searching for K underwater. The six novice students followed his lead.

K, meanwhile, had returned to the point of separation but could not find the missing members of his team, as they had already drifted and then actively swam in the opposite direction. He had lost them completely.

The separated group, now led by the inexperienced assistant, swam several dozen meters further offshore. The assistant checked the victim's air pressure gauge and noted it was running low. He then led the group to the surface. However, faced with choppy water and wind, he deemed it too difficult to move on the surface and instructed the students to submerge once again to continue moving underwater.

The victim, following these instructions, re-submerged. Already low on air and in an increasingly stressful situation, the victim exhausted their air supply, fell into a state of panic, and was unable to take appropriate life-saving measures. They subsequently drowned.

The Legal Proceedings and the Central Issue: Causation

K was charged with and convicted of professional negligence resulting in death in the lower courts. The case was appealed to the Supreme Court. The defense argued that K's actions were not the direct cause of the victim's death. They contended that the chain of causation was broken by the intervening—and arguably poor—decisions of the assistant instructor (choosing to search for K underwater instead of surfacing immediately, and later ordering a re-submersion on low air) and the victim's own panic.

The core legal question for the Supreme Court was this: Was the defendant's negligent act of abandoning his students causally linked to the victim's death, or were the subsequent actions of the assistant and the victim independent, intervening causes that absolved the defendant of ultimate responsibility?

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Upholding Causation Through "Inducement"

The Supreme Court rejected the appeal and upheld the conviction. The court's reasoning provides a masterclass in the nuanced application of causation principles.

The Court held:

"The defendant's act, in the course of a night diving lecture, of carelessly moving away from and losing sight of the students without paying attention to their movements, was in itself an act that possessed the inherent risk of causing the victim—who was likely unable to take appropriate measures to adapt to the situation without proper instruction and guidance from a leader—to exhaust their air underwater and, consequently, die without being able to take appropriate action. While it is undeniable that the assistant instructor and the victim engaged in inappropriate behavior after losing sight of the defendant, that behavior was induced by the defendant's aforementioned act. Therefore, this does not preclude the affirmation of a causal relationship between the defendant's act and the victim's death."

The key word here is "induced" (誘発された, yūhatsu sareta). The Court did not view the actions of the assistant and the victim as fresh, independent choices made in a vacuum. Instead, it saw them as direct and foreseeable consequences of the perilous situation the defendant had single-handedly created.

Deconstructing the "Inducement" Doctrine

The Court's decision hinges on a sophisticated understanding of how a leader's negligence can create a cascade of failures. Let's break down the core components of this reasoning.

1. The Creation of an Inherently Dangerous Situation

The Court first established that the defendant's act was not merely a minor lapse. By losing his students during a challenging night dive, he did more than just break a rule; he fundamentally altered the nature of the activity. A guided night dive for novices is a managed risk. An unguided night dive where novices are lost at sea is a crisis.

The court specifically recognized the heightened dangers:

- Environmental Factors: Poor visibility and darkness increase anxiety and fear.

- Psychological Impact: This fear accelerates air consumption.

- Skill Deficiency: Novice divers, especially the victim, lacked the experience and composure to handle an emergency on their own. They were entirely dependent on the instructor's guidance for everything from navigation to air management and emergency procedures.

K's act of moving on without confirming his group was intact instantly plunged them into this high-risk scenario. His negligence was not passive; it actively created the conditions for a fatal outcome. The "risk" the Court speaks of was not just a theoretical possibility but a potent and immediate danger.

2. The Superior Position and Duty of the Defendant

A critical, though implicit, element of the ruling is the power dynamic. K was not just another diver; he was the expert, the leader, the person in command. The students and the assistant instructors had placed their safety and trust in his hands. He possessed superior knowledge, skill, and experience.

This hierarchical relationship is central to the "inducement" concept. The Court recognized that when such a leader suddenly disappears, it creates a vacuum of command and a sense of desperation. The remaining individuals are not operating as free agents. Their actions are colored by the panic, confusion, and psychological pressure that stems directly from the leader's abandonment.

The assistant instructor's decision to search for K underwater, while flawed in hindsight, is understandable as a panicked reaction aimed at restoring the proper order of command—finding the leader. The students' choice to follow the assistant was similarly not a fully independent decision but an act of reliance on the only remaining figure of authority, however inexperienced.

3. "Inducement" vs. A Simple Intervening Act

This is where the court's logic is most refined. In many negligence cases, a "grossly negligent" intervening act by a third party can break the chain of causation. One might argue that the assistant instructor's decision to order a re-submersion when he knew the victim's air was low constituted such an act.

However, the Supreme Court's "inducement" framework reframes this. The assistant's poor judgment was not an isolated event. It was a product of the crisis environment K had created. The assistant, who the court noted was himself very inexperienced as a leader, was forced into a decision-making role for which he was unprepared, precisely because of K's negligence. K's failure did not just create the physical danger of being lost at sea; it also created the psychological conditions that would lead an inexperienced subordinate to make poor decisions under extreme pressure.

Therefore, the assistant's actions and the victim's subsequent panic were not seen as superseding causes but as tragic, foreseeable links in the causal chain that K himself had forged. They were part of the very risk he unleashed when he failed in his primary duty of care: to keep his students safe and accounted for.

Broader Implications in Japanese Jurisprudence

This case is often studied alongside another significant decision concerning causation, the "Judo Practitioner Case" (Decision of the Supreme Court, May 11, 1988). In that case, a judo practitioner provided "treatments" for a patient's common cold that were described as "utterly bizarre." The patient, placing absolute trust in the practitioner, followed the instructions faithfully, his condition worsened, and he died. The court found causation, reasoning that the defendant's position of authority and the victim's absolute reliance meant the victim's actions (following the harmful advice) were not truly independent choices that would break the causal chain.

The Scuba Diving case builds on this foundation. It takes the principle from the controlled environment of a patient-practitioner relationship and applies it to the chaotic, high-risk environment of an outdoor activity. In both instances, the courts affirmed that a person in a position of superior knowledge and trust bears a heavy responsibility. Their negligence can be seen as the legal cause of a harmful outcome, even if that outcome is immediately precipitated by the actions of others, if those actions were "induced" by the trust placed in, and the crisis created by, the defendant.

This contrasts with other causation scenarios, such as the "Osaka Nanko Case" (Decision of the Supreme Court, November 20, 1990). In that case, the defendant inflicted a mortal wound on the victim, and subsequent medical malpractice only served to hasten the death that was already made inevitable by the initial injury. There, causation was affirmed because the defendant's act had already created the "cause of death."

The Scuba Diving case is more nuanced. The defendant's act did not create an inevitable death. It created a risk of death that was realized through the induced, faulty actions of others. It holds the defendant responsible not just for the physical situation he created, but for the predictable human reactions to that situation.

Conclusion: A Heavy Mantle of Responsibility

The 1992 Supreme Court decision on the Kushimoto scuba diving incident is a powerful statement on the nature of duty and causation. It establishes that a leader's responsibility does not end at simply performing a task; it extends to managing the entire environment of risk, which includes the foreseeable psychological reactions of those under their care.

The "inducement" doctrine serves as a vital legal tool to prevent a negligent actor from deflecting blame onto the panicked or flawed responses that their own negligence predictably provokes. For anyone in a position of leadership, instruction, or expert authority—be it a corporate manager, a financial advisor, or a wilderness guide—the message is clear: when you create the mission, you are not only responsible for your own actions but also for the foreseeable, and induced, reactions of those who have placed their trust in you. Your failure can become their failure, but the ultimate responsibility may still lie at your feet.