Causation in Medical Omissions: Japan's Supreme Court on Delayed Cancer Diagnosis and Patient Death

Date of Judgment: February 25, 1999 (Heisei 11)

Case Reference: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench, 1996 (O) No. 2043

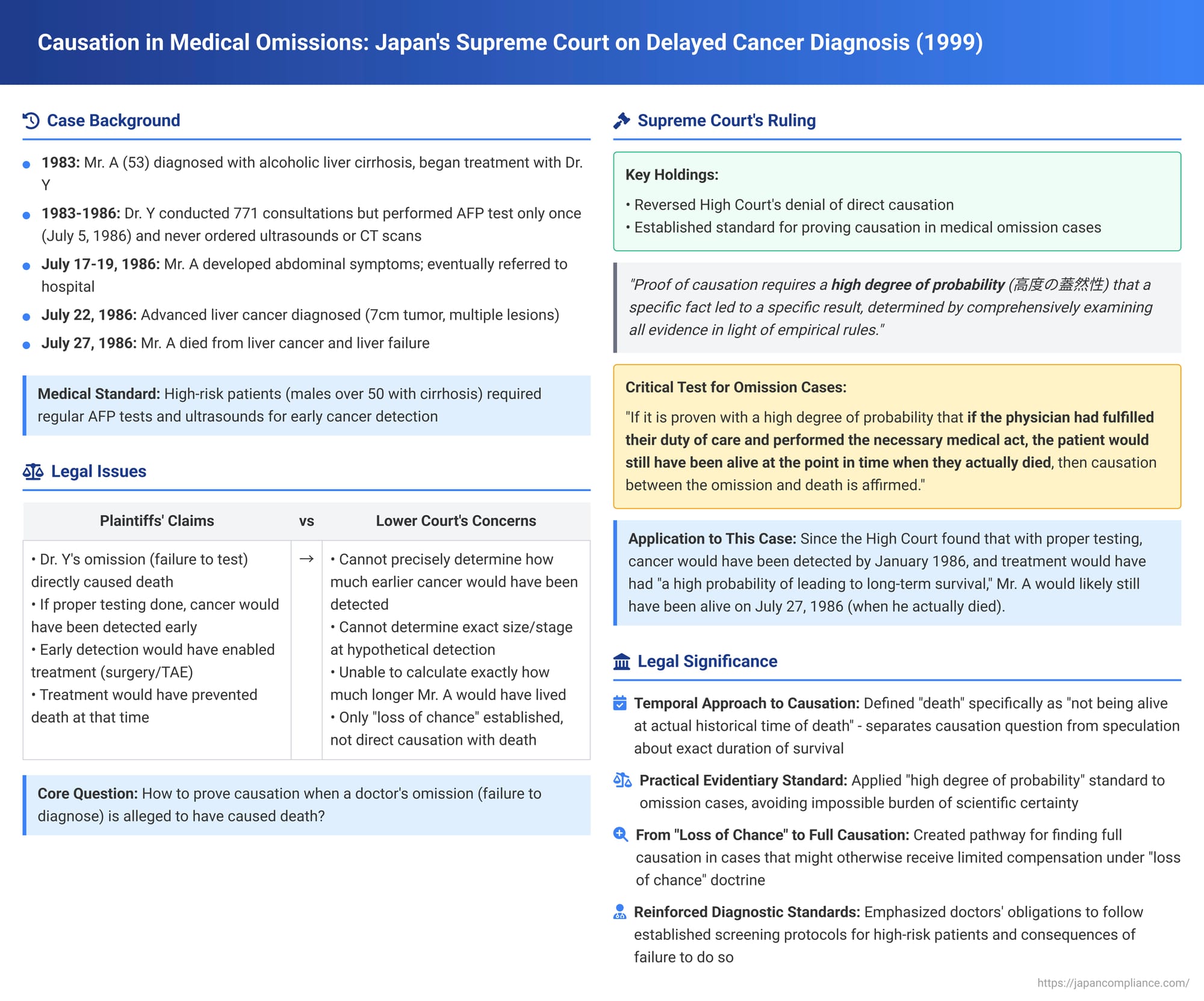

In a significant ruling on February 25, 1999, the Supreme Court of Japan addressed the complex issue of establishing a causal link between a physician's failure to perform necessary diagnostic procedures (an omission) and the subsequent death of a patient. This case, involving a delayed diagnosis of liver cancer in a high-risk patient, is notable for clarifying how causation should be approached when timely medical intervention might have prolonged life, even if it could not guarantee a complete cure. The Court reaffirmed its standard of proving causation by a "high degree of probability" and applied it specifically to situations of medical omission.

Factual Background: A Patient with Liver Cirrhosis and Missed Cancer Detection

The case concerned Mr. A, who was born in September 1930. Around October 1983 (Showa 58), he was diagnosed with alcoholic liver cirrhosis. On November 4, 1983, Mr. A entered into a medical care contract with Dr. Y, a physician specializing in liver diseases, for the ongoing management of his condition.

It was recognized that Mr. A, being a male in his 50s with liver cirrhosis, belonged to a high-risk group for developing hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), a type of liver cancer. This meant that diligent monitoring for the early detection of HCC was a critical part of his medical care. The established medical best practices at the time for early HCC detection in such high-risk patients included:

- Regular blood tests to measure Alpha-Fetoprotein (AFP) levels, a tumor marker.

- Regular abdominal ultrasound examinations, to be used in conjunction with AFP tests.

- If cancer was suspected based on these screening tests, further diagnostic procedures such as CT scans were necessary to confirm the diagnosis and determine the extent of the disease.

Dr. Y, as a liver specialist, was aware of these diagnostic requirements and the importance of early detection for improving prognosis in HCC cases.

Dr. Y's Actual Course of Treatment for Mr. A (November 1983 – July 19, 1986):

Over a period spanning from November 4, 1983, to July 19, 1986 (Showa 61), Dr. Y conducted a total of 771 consultations with Mr. A. However, the care provided during these numerous visits primarily consisted of prescribing liver-protective medications and performing physical examinations (palpations). Critically, with respect to the recommended HCC screening tests:

- Dr. Y performed an AFP blood test on Mr. A only once, on July 5, 1986.

- No abdominal ultrasound examinations or CT scans were initiated or recommended by Dr. Y for Mr. A throughout this nearly three-year period.

The AFP test conducted on July 5, 1986, showed a moderately elevated level (110 ng/ml, where normal is <20 ng/ml), but Dr. Y reportedly informed Mr. A that the cancer reaction was negative.

Late Diagnosis and Patient's Death:

Around July 17, 1986, Mr. A began to develop symptoms such as abdominal distension and pain in the right upper quadrant. He consulted Dr. Y, who initially diagnosed muscle pain. As his condition worsened, Dr. Y referred Mr. A to B Hospital on July 19.

At B Hospital, investigations revealed that Mr. A had advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. A definitive diagnosis was made on July 22, 1986. Imaging studies showed multiple tumors in his liver, with the largest being approximately 7cm x 7cm, and others around 2.6cm x 2.5cm, as well as other lesions and tumor thrombus in the portal vein. Due to the advanced stage of the cancer, curative treatment options were no longer feasible.

Mr. A passed away on July 27, 1986. The causes of death were recorded as hepatocellular carcinoma and liver failure.

Mr. A's surviving family members (X et al.) filed a lawsuit against Dr. Y, seeking approximately 70 million yen in damages. Their primary claim was based on tort (medical negligence), with a secondary claim for breach of the medical care contract. They argued that Dr. Y's failure to perform the necessary cancer screening tests led to a delay in diagnosis, depriving Mr. A of the opportunity for timely and potentially life-prolonging treatment.

Lower Court Proceedings: Wrestling with Causation and Lost Life Expectancy

- First Instance Court (Fukuoka District Court, Kokura Branch): The trial court found in favor of the plaintiffs on their primary claim (tort) and awarded partial damages of 3.6 million yen.

- High Court (Fukuoka High Court): The High Court upheld the first instance court's decision, dismissing appeals from both the plaintiffs and Dr. Y. Its key findings were:

- Negligence Established: Dr. Y had breached his duty of care. As a specialist treating a high-risk patient like Mr. A, he should have conducted regular AFP tests and abdominal ultrasounds (at least twice a year) and followed up with further investigations like CT scans if cancer was suspected. His failure to do so over nearly three years constituted clear negligence.

- Probability of Earlier Detection: Had Dr. Y fulfilled his diagnostic duties, there was a "high degree of probability" that Mr. A's HCC could have been detected much earlier, at the latest by January 1986.

- Potential Efficacy of Early Treatment: The High Court acknowledged that if HCC is detected at an early stage (e.g., tumors less than 2cm in diameter), surgical resection offers a significant chance of cure or long-term survival. Other treatments like Transarterial Embolization (TAE) could also be effective for larger tumors (e.g., over 3cm) or in combination with other therapies to achieve some prolongation of life. Thus, if Mr. A's cancer had been detected earlier through Dr. Y's due care, he could have received appropriate treatment that offered "some degree of life-prolonging effect."

- Direct Causation with Death Denied: Despite these findings, the High Court concluded that it could not affirm a "considerable causal relationship" (相当因果関係 - sōtō inga kankei) between Dr. Y's negligence (failure to test) and Mr. A's death. The reasoning was that due to various uncertainties—such as the precise size and stage the cancer would have been at the time of hypothetical earlier detection, and the variable growth rates of HCC—it was impossible to definitively confirm how much longer Mr. A might have lived. The High Court rejected the plaintiffs' attempt to calculate damages based on 5-year survival rates for cancers detected under 2cm, as it was not definitively established that Mr. A's cancer would have been found at that very early stage.

- Compensation for "Loss of Chance": Because direct causation with death (defined as death at that specific point versus some unascertainable later point) was denied, the High Court instead awarded damages based on the concept of "loss of chance." It found that Mr. A had been deprived of the opportunity to receive appropriate treatment that could have offered a possibility of prolonged life. For this infringement, it awarded 3 million yen in consolation money (for Mr. A's mental suffering) and 600,000 yen for attorney's fees.

The plaintiffs, dissatisfied with the denial of full compensation for wrongful death, appealed to the Supreme Court, arguing that a direct causal link between Dr. Y's negligence and Mr. A's death should have been recognized.

The Supreme Court's Decision (February 25, 1999)

The Supreme Court overturned the High Court's judgment with respect to the plaintiffs' losing portion (i.e., the denial of full compensation for death due to lack of direct causation) and remanded the case for further proceedings. The Court's decision provided a crucial clarification on how to approach causation in cases of medical omission.

1. Reaffirming the Standard of Proof for Causation (判旨Ⅰ - Hanshi I):

The Court began by reiterating its established standard for proving causation in litigation, quoting its own landmark ruling in the 1975 Lumbar Puncture Cerebral Hemorrhage Causation Case (Supreme Court, Showa 50.10.24 – Case 59 in the PDF series):

"Proof of a causal relationship in litigation does not require natural scientific proof that permits no single doubt whatsoever. Rather, it is the proof of a high degree of probability (高度の蓋然性 - kōdo no gaizensei) that a specific fact led to the occurrence of a specific result, which is to be determined by comprehensively examining all evidence in light of empirical rules (経験則 - keikensoku). The determination thereof requires that an ordinary person could hold a conviction of its truthfulness to a degree that leaves no room for doubt, and this is sufficient."

2. Applying the Standard to Medical Omissions and Patient Death (判旨Ⅱ - Hanshi II):

The Supreme Court explicitly extended this standard to situations involving a physician's omission (a failure to perform a necessary medical act) and the patient's subsequent death:

- "The above [standard of proof] is no different in determining the existence or non-existence of a causal relationship between a physician's omission to perform a medical act that should have been performed in accordance with the duty of care, and the patient's death."

- The Key Formulation for Causation in Omission Cases: "If it is proven with a high degree of probability—upon comprehensive examination of all evidence including statistical data and other medical knowledge in light of empirical rules—that the physician's said omission resulted in the patient's death at that particular point in time; in other words, that if the physician had fulfilled their duty of care and performed the [necessary] medical act, the patient would still have been alive at the point in time when they actually died, then the causal relationship between the physician's omission and the patient's death is to be affirmed."

- Separation of Causation from Quantum of Damages: "For what period the patient might have survived beyond that point [the actual time of death] is primarily a matter to be considered in calculating lost profits and other damages; it does not directly affect the determination of the existence or non-existence of the aforementioned causal relationship [with death at that specific time]."

3. Application to Mr. A's Case (判旨Ⅲ - Hanshi III):

Applying this framework, the Supreme Court re-evaluated the High Court's findings:

- The Supreme Court noted that the High Court itself had found that if Dr. Y had conducted appropriate examinations, HCC of a degree where surgical resection was possible "could have been discovered, at the latest, by January 1986," approximately six months before Mr. A's actual death. The High Court had also acknowledged that if such treatment had been performed, "there was a high probability of leading to long-term survival," and that even with TAE therapy, "prolongation of life was also possible."

- Supreme Court's Interpretation of the High Court's Findings: The Supreme Court stated: "The purport of these [High Court] findings is understood to be that if Mr. A's hepatocellular carcinoma had been discovered in January 1986, it is recognized with a high degree of probability that by thereafter receiving ordinary medical treatment according to the medical standard of the time, he would still have been alive on July 27, 1986 [the actual date of his death]."

- Affirmation of Causation with Death (at that time): "This being the case, unless it were argued that treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma is entirely ineffective (which is not the situation in this case), it should be said that a causal relationship exists between Dr. Y's aforementioned breach of duty of care and Mr. A's death [on July 27, 1986]."

The Supreme Court thus found that the High Court, despite its own factual findings which strongly suggested that timely diagnosis and treatment would have allowed Mr. A to live beyond his actual date of death, had erred in its legal interpretation by denying a direct causal link to his death (as defined by the Supreme Court). The determination of how much longer he might have lived was a separate issue for the damages phase.

Analysis and Implications: A Pragmatic Approach to Causation in Medical Omissions

This 1999 Supreme Court decision is of profound importance in Japanese medical malpractice law, particularly for cases involving alleged harm due to a physician's failure to act:

- Clarifying Causation for Omissions: The judgment provides a clear and workable framework for establishing causation when a doctor's omission (e.g., failure to diagnose, failure to treat, failure to refer) is alleged to have resulted in a patient's death.

- Defining "Death" for Causation Purposes: The crucial analytical step taken by the Supreme Court was to define the "result" of death in a specific temporal context: the patient not being alive at the actual historical time of their death. If it can be shown with a high degree of probability that, but for the physician's omission, the patient would have been alive on that specific date, then causation between the omission and "death (at that time)" is established.

- Separating Fact of Death from Duration of Lost Life: This approach elegantly separates the factual question of whether the omission caused death (at that point in time) from the more speculative question of how much longer the patient would have lived. The latter becomes relevant primarily for quantifying damages (such as lost future income or the extent of non-pecuniary loss), not for the initial finding of causation with the fact of death. This resolved the High Court's difficulty in affirming full causation because it could not precisely determine the lost quantum of life.

- Consistent Application of the "High Degree of Probability" Standard: The ruling reaffirms the general standard of proof for causation laid down in the 1975 Lumbar Puncture Case and explicitly makes it applicable to cases of medical omission, ensuring consistency in judicial approach.

- Potential Shift from "Loss of Chance" to Full Causation: This decision provides a pathway for establishing full causation (and thus potentially full damages for wrongful death) in certain omission cases that might previously have been compensated only under the "loss of a substantial chance" doctrine. If the evidence supports a high probability that the patient would have survived beyond their actual date of death with proper care, then direct causation with that "timely death" is affirmed. The "loss of chance" doctrine might still apply where even this threshold is not met, but a significant possibility of a better outcome was nonetheless lost.

- Underlining the Importance of Adhering to Diagnostic Standards: While the case focused on causation, the underlying facts highlight the severe consequences of a physician's prolonged failure to adhere to established medical standards for screening and early detection of serious diseases in high-risk patients. Dr. Y's multi-year omission of standard HCC screening for a patient with liver cirrhosis was a clear and egregious breach of his duty of care.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's February 25, 1999, judgment is a critical precedent in Japanese medical malpractice law. By providing a pragmatic and legally sound framework for establishing causation in cases of medical omission leading to a patient's death, it ensures that the significant difficulties in proving exactly how long a patient might have lived do not preclude a finding that a physician's negligence indeed caused that patient's death at the time it occurred. This ruling underscores the judiciary's commitment to ensuring that patients or their families can obtain just redress when a physician's failure to act, in breach of their duty of care, leads to a premature and preventable death. It clarifies that the law will hold physicians accountable not only for negligent actions but also for negligent inactions that result in such tragic outcomes.