Causation, Confusion, and Complicity: Japan's Supreme Court on Gang Assaults and Homicide

Case Title: Case of Injury, Injury Causing Death

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

Decision Date: March 24, 2016

Introduction

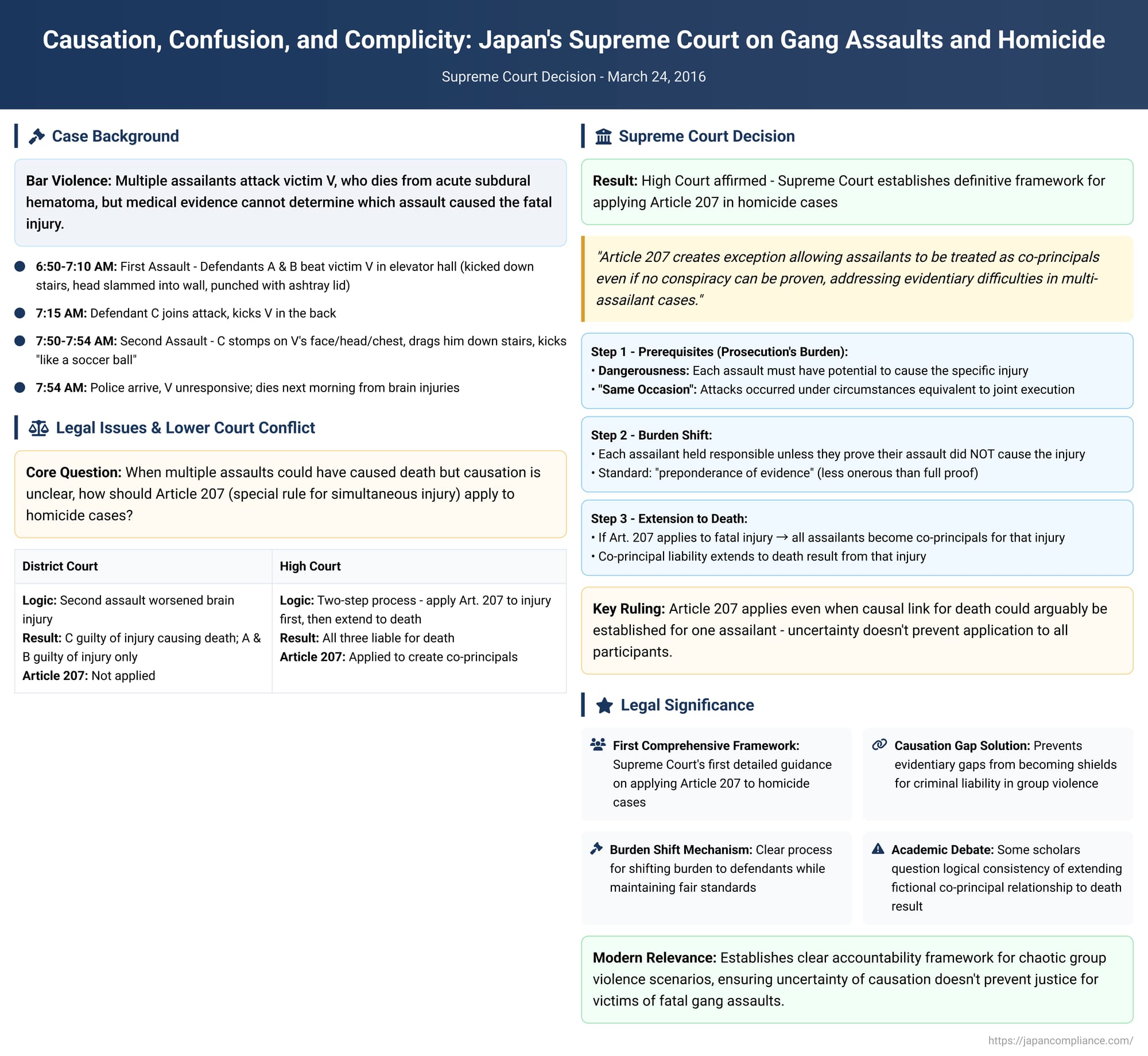

Imagine a chaotic, violent scenario: a victim is attacked by multiple assailants, none of whom are acting in a coordinated conspiracy. The victim tragically dies from a specific injury, but forensic evidence cannot determine which of the several attacks delivered the fatal blow. In such a case, who is legally responsible for the death? Can all assailants be convicted of homicide, or does the uncertainty of causation allow some, or even all, to escape liability for the gravest consequence of their actions?

This evidentiary nightmare is what Article 207 of the Penal Code of Japan, known as the "special rule for simultaneous injury," is designed to solve. In a landmark decision on March 24, 2016, the Supreme Court of Japan provided its first comprehensive framework for how this rule applies in cases of injury causing death (shōgai chishi). The Court clarified the rule’s purpose, its prerequisites, and its method of application, establishing a definitive approach to ensure accountability in the fog of a multi-assailant attack.

The Facts: A Brutal and Complicated Assault

The case arose from a violent altercation at a bar in a commercial building. The facts, as established by the courts, paint a grim picture:

- The First Assault: In the early morning hours, a dispute over a credit card payment arose between the victim, V, and employees of the bar, defendants A and B. After V left the bar, A and B pursued him into the building’s elevator hall. Between approximately 6:50 AM and 7:10 AM, A and B, acting in concert, subjected V to a vicious beating. A kicked V down a flight of stairs, slammed his face into an elevator wall, and, after V was on the floor, punched him with his fists and an ashtray lid, and smashed his head against the floor. B also hit V's head on a stand-up ashtray, kicked him, and beat him while mounted on top of him.

- The Second Assault: Around 7:04 AM, defendant C, a customer at the bar, appeared in the elevator hall. After a brief interval, he joined the attack. At approximately 7:15 AM, C kicked the prone victim in the back. A short while later, after V attempted to flee and was caught on a staircase by another employee, C escalated his assault. Between roughly 7:50 AM and 7:54 AM, C stomped on the face, head, and chest of the subdued victim, dragged him down the stairs by his legs, and repeatedly kicked his head and abdomen "like a soccer ball." He delivered a final kick to V's face as V began to snore heavily.

- The Fatal Result: When police arrived at 7:54 AM, V was unresponsive. He was rushed to the hospital and underwent emergency brain surgery but died the next morning. The cause of death was an acute subdural hematoma leading to acute cerebral swelling. Critically, while both the First Assault (by A and B) and the Second Assault (by C) were independently capable of causing this fatal injury, it was medically impossible to determine which specific assault was the cause.

The Legal Conundrum: A Clash of Courts

The impossibility of pinpointing the fatal blow created a legal challenge that led to conflicting judgments in the lower courts.

The District Court's Approach: Avoiding a "Gap in Liability"

The Nagoya District Court interpreted Article 207's purpose as being a tool to prevent an "unreasonable situation where no one is held responsible for the death". It reasoned that even if the fatal hematoma had been caused by the First Assault, the Second Assault by C surely worsened it. This, the court found, was sufficient to establish a causal link between C's actions and the death. Because C could be held responsible for the death, there was no "gap in liability" that needed to be filled by the special rule of Article 207.

Consequently, the District Court did not apply Article 207. It convicted A and B only of the lesser crime of causing injury (shōgai), while finding C guilty of the more serious crime of injury causing death (shōgai chishi).

The High Court's Reversal: A Two-Step Method

The Nagoya High Court rejected the District Court's logic and reversed its decision. It argued that the lower court had made a fundamental error by jumping straight to the question of causation for the death. The High Court noted that this approach ignored the plain text of Article 207, which is triggered by uncertainty regarding the cause of the injury. Under the District Court’s logic, a bizarre outcome would occur where no one was held responsible for causing the fatal subdural hematoma itself.

Instead, the High Court articulated a two-step process:

- First, focus only on the fatal injury (the hematoma). Since its cause is unknown, Article 207 applies to all three defendants. This treats them all as co-principals for the act of causing that specific injury.

- Second, because all three are legally deemed co-principals for the fatal injury, they must also bear responsibility as co-principals for the death that resulted from that injury.

The case was then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Definitive Framework for Article 207

The Supreme Court of Japan affirmed the High Court’s reasoning and, in doing so, laid out a clear and authoritative framework for applying Article 207 in homicide cases.

The Purpose of Article 207

The Court began by explaining the rule's rationale. In cases involving assaults by two or more people, it is often difficult to prove causation for the resulting injury. Article 207 addresses this by creating an exception, allowing the assailants to be treated as co-principals (kyōhan) even if no conspiracy can be proven.

Step 1: The Prerequisites (The Prosecution's Burden)

The Court clarified that before Article 207 can be invoked, the prosecutor must prove two essential prerequisites:

- Dangerousness: Each independent assault must have possessed the potential danger to cause the specific injury that resulted.

- "On the Same Occasion": The assaults must have been carried out "on the same occasion" (dōitsu no kikai). This means the attacks occurred under circumstances where they can be externally evaluated as being equivalent to a joint execution. The Court’s explicit articulation of this "same occasion" requirement was a significant clarification of the law.

Step 2: The Consequence (The Burden Shifts to the Defense)

Once the prosecution proves these two prerequisites, the legal consequence is a shift in the burden of proof.

- Each assailant is held responsible for the injury unless they can affirmatively prove that their own assault did not cause it. The Court’s use of the term risshō (to establish proof) rather than the stronger shōmei (to certify) has been interpreted to mean that the defendant may only need to meet a "preponderance of the evidence" standard, a less onerous burden. Indeed, the trial court in the remanded case adopted this very standard.

Step 3: Extending Liability to the Death Result

Finally, the Court cemented the two-step logic for homicide cases.

- If the prerequisites for Article 207 are met regarding the fatal injury, the rule applies, and all assailants are treated as co-principals for that injury.

- From there, liability extends to the ultimate consequence. The assailants, now legally responsible for the fatal injury, are also held responsible for the death that resulted from it.

- Crucially, the Court added that this rule applies even in cases like this one, where a causal link for the death could arguably be established for one of the assailants. The possibility of pinning the death on one person does not prevent the application of Article 207 to all participants.

Scholarly Debate and Conclusion

While the Supreme Court's decision provides a clear, practical solution, it has not been without academic critique. Some scholars argue there is a logical inconsistency in the Court's reasoning. They point out that Article 207 creates a fictional co-principal relationship for the "injury" only. The Court's framework then uses this legal fiction as a basis to extend liability to the separate result of "death," which is not explicitly covered by the rule's effect. These critics suggest that the only way to logically justify holding all parties liable for the death is to interpret the word "injury" in Article 207 as encompassing "death" itself—a position closer to the District Court’s initial approach.

Despite this academic debate, the 2016 Supreme Court decision stands as the authoritative guide. It establishes a clear, sequential process that resolves the dangerous evidentiary gap in multi-assailant homicides. By focusing first on the predicate injury and creating a shared responsibility for it, the Court ensures that all who participate in a chaotic and fatal group assault can be held accountable for the victim's death, reinforcing the principle that uncertainty of causation should not become a shield for criminal liability.