Causation by Omission: Japan's Supreme Court on Abandonment, Stimulants, and the "Eight or Nine out of Ten" Chance of Survival

Date of Decision: December 15, 1989

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

Case Name: Stimulant Control Law Violation, Abandonment by a Guardian Resulting in Death Case

Case Number: 1989 (A) No. 551

I. Introduction: When Inaction Leads to Death – The Question of Causation

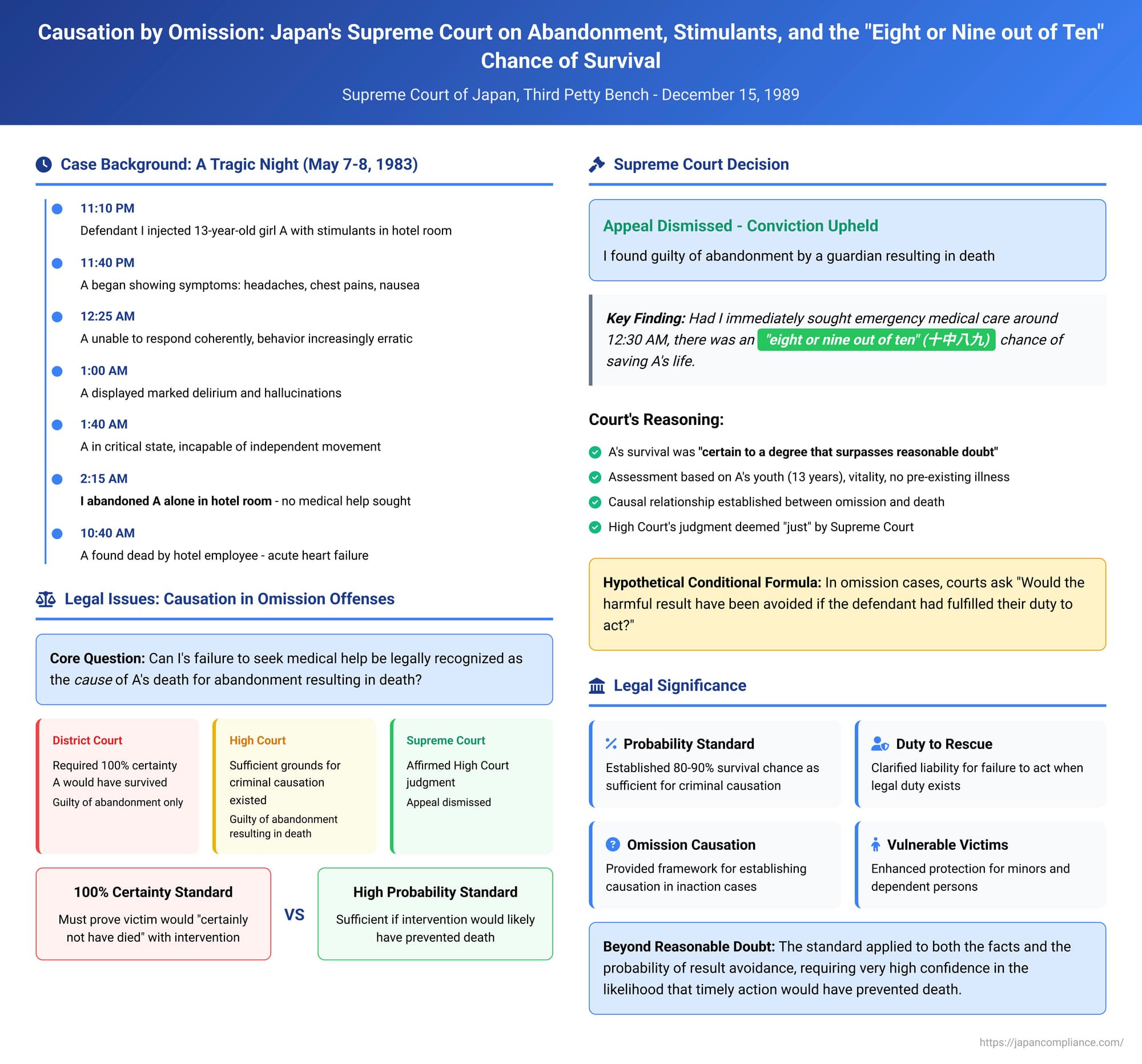

On December 15, 1989, the Third Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan issued a critical decision in a case that tragically involved a 13-year-old girl, A, who died after being injected with stimulants by the defendant, I, and subsequently abandoned by him. While I's actions in administering the drugs were a clear violation, the core legal battleground was whether his subsequent failure to act—his omission to seek medical help as A's condition deteriorated—could be legally recognized as the cause of her death, thereby holding him responsible for abandonment by a guardian resulting in death. This case delves into the complexities of establishing criminal causation for offenses of omission, particularly the degree of certainty required to prove that timely action would have prevented the fatal outcome.

II. A Tragic Night: The Facts of the Case

The events leading to A's death unfolded on the night of May 7, 1983, and into the early hours of May 8. According to the findings of the first instance court:

- Around 11:10 PM on May 7, in a hotel room, I injected A, a 13-year-old girl, with an aqueous solution containing stimulants.

- By approximately 11:40 PM, A began to exhibit distressing symptoms, including headaches, chest pains, and nausea.

- Her condition worsened significantly, and by 12:25 AM on May 8, she was unable to respond coherently to I's questions, and her behavior became increasingly erratic.

- From around 1:00 AM, A displayed marked delirium, consistent with hallucinatory symptoms induced by the stimulants.

- By approximately 1:40 AM, A was in a critical state, incapable of normal independent movement.

Despite this rapidly deteriorating situation, I made no effort to secure medical attention for A. He did not call a doctor or ambulance, nor did he alert the hotel staff to her grave condition. Instead, around 2:15 AM, I left A alone in the hotel room and departed from the premises. Later that morning, around 10:40 AM, A was discovered dead by a hotel employee. The cause of death was acute heart failure due to the stimulants.

III. The Legal Journey: Conflicting Views on Causation

The central legal question as the case progressed through the courts was whether I's failure to seek medical assistance for A constituted a legally sufficient cause of her death.

- First Instance (Sapporo District Court – April 11, 1986): The District Court approached the issue of causation with a demand for a very high degree of certainty. It reasoned that for I to be held criminally liable for A's death due to his abandonment by omission, it had to be proven that A "certainly would not have died" had I not abandoned her by failing to act. The court noted that expert medical testimonies, while suggesting a possibility of survival with timely emergency care, could not definitively state that A would have been saved with 100% certainty. There was also an inability to rule out the possibility that A might have died shortly after I left, regardless of any intervention at that point. Given this, the court concluded that reasonable doubt remained as to whether A's life would have been saved even if medical help had been sought immediately when her abnormal symptoms first appeared. Consequently, I was convicted of abandonment by a guardian (hogo sekininsha iki), but not the more severe offense of abandonment by a guardian resulting in death (hogo sekininsha iki chishi).

- Appellate Court (Sapporo High Court – January 26, 1989): The High Court took a different view. It stated that the critical determination was whether A's death could be "evaluated under criminal law" as having been caused by I's failure to provide protection. The High Court opined that the inability of medical experts to guarantee a 100% chance of survival, or to pinpoint the exact moment at which intervention would have ensured survival, did not automatically negate the existence of criminal causation. Finding "sufficient grounds to recognize criminal causation," the High Court overturned the District Court's decision on this count and found I guilty of abandonment by a guardian resulting in death. I subsequently appealed this judgment to the Supreme Court.

IV. The Supreme Court's Stance: "Eight or Nine out of Ten" as Sufficient Certainty

The Supreme Court of Japan dismissed I's appeal. In its decision, the Court specifically addressed the issue of causation for the charge of abandonment resulting in death, reviewing the High Court's findings ex officio (on its own initiative).

The Supreme Court highlighted the following key aspects from the High Court's findings:

- Around 12:30 AM, when A had fallen into a delirious state due to the stimulants administered by I (and his accomplices, as mentioned in the Supreme Court text), had I immediately sought emergency medical care, there was an "eight or nine out of ten" (十中八九 - jitchū hakku) chance of saving A's life. This assessment took into account her youth (13 years old at the time), her strong vitality, and the absence of any particular pre-existing illnesses.

Based on this probability, the Supreme Court concluded:

- A's survival, had prompt medical action been taken, was "certain to a degree that surpasses reasonable doubt" (合理的な疑いを超える程度に確実 - gōritekina utagai o koeru teido ni kakujitsu).

- Therefore, it was appropriate to recognize a causal relationship under criminal law between I's omission—his act of leaving A unattended in the hotel room without seeking necessary medical help—and her subsequent death from acute heart failure due to stimulants, which occurred sometime between approximately 2:15 AM and 4:00 AM in that room.

The Supreme Court thus affirmed the High Court's judgment, finding I guilty of abandonment by a guardian resulting in death, as just.

V. The Challenge of Causation in Omission Offenses

This case underscores the inherent difficulties in establishing causation for crimes of omission. An omission offense occurs when an individual fails to perform a legally mandated action, and this failure results in a prohibited harm. Unlike commission offenses, where there's often a direct physical link between the defendant's act and the result (e.g., pulling a trigger and a bullet hitting a victim), causation in omission cases is more abstract. It involves a counterfactual, hypothetical inquiry: what would have happened if the defendant had performed the required action?

The generally accepted method for determining this is often referred to as the "hypothetical conditional formula". This involves asking: If the defendant had fulfilled their duty to act, would the harmful result have been avoided? If the answer is yes, then a causal link can, in principle, be established. This contrasts with the standard "but-for" test (condition sine qua non) used as a starting point for commission offenses, which asks whether the result would have occurred "but for" the defendant's positive act. In omission cases, removing the (non-)act doesn't change the outcome; instead, one must hypothetically add the required action and assess its likely impact.

VI. "Beyond Reasonable Doubt" vs. Probability of Avoidance

A significant point of discussion arising from the Supreme Court's decision is its use of the phrase "certain to a degree that surpasses reasonable doubt." This phrase is the well-established standard of proof required in criminal trials in Japan (and many other jurisdictions) for a court to convict a defendant; every element of the crime must be proven to this high standard.

In this case, the Supreme Court applied this phrase to describe the likelihood of A's survival if I had acted. This raises a nuanced conceptual point:

- The degree of probability of result avoidance: This refers to how likely it must be that the required action would have averted the harm. Is a 50% chance enough? 75%? 99%? This is a question about the substantive legal definition of causation in omission offenses.

- The standard of proof: This refers to the level of confidence the court must have in the facts presented to it. For example, if the law requires an 80% probability of result avoidance for causation, then the fact that there was indeed an 80% probability must itself be proven "beyond reasonable doubt."

These two concepts are theoretically distinct. However, in the context of omission offenses, where the causal link itself is not a directly observable physical process but rather a hypothetical reconstruction, the line between the substantive requirement for causation (degree of probability) and the evidentiary standard for proving it can appear blurred. The court must be convinced beyond reasonable doubt that a sufficiently high probability of avoidance existed.

VII. Interpreting "Eight or Nine out of Ten"

The Supreme Court's reliance on the "eight or nine out of ten" (roughly 80-90%) chance of survival is central to its finding. The question arises: what does this specific probability signify in establishing causation "beyond reasonable doubt"?

- One interpretation is that the Supreme Court considered an 80-90% chance of survival to be, in itself, a level of certainty that satisfies the legal requirement for causation in such grave circumstances. This might imply that 100% certainty of survival is not required, and a very high probability suffices.

- Another way to view it is that the evidence supporting the "eight or nine out of ten" chance was so strong that the Court was convinced beyond reasonable doubt that this high probability indeed existed. The Court then deemed this very high, and confidently established, probability as legally sufficient to attribute causation for A's death to I's omission.

This phrasing has led to academic discussion about whether, by accepting an 80-90% probability (a figure sometimes associated with the "high probability" standard in civil litigation rather than the stricter criminal standard for ultimate facts), the Court might be subtly adjusting the threshold for establishing the causal link in omission cases, even while employing the familiar language of "beyond reasonable doubt." The practical consequence is that it provides a benchmark, albeit one open to interpretation, for future cases involving failures to act.

VIII. Broader Perspectives: The Definition of "Result" and Risk Theories

The analysis of causation in omission cases is further complicated by how one defines the "result" that must be avoided. In a death case, does the required action need to have guaranteed long-term survival, or is it sufficient if it would have merely prolonged life, even for a short period?

Some Japanese judicial precedents and legal commentaries suggest that preventing death "within a short period" or offering a significant "possibility of survival" might be enough in certain contexts, such as medical non-treatment cases involving vulnerable newborns. For example, a 1988 Supreme Court decision considered a scenario where a newborn had about a 50% chance of survival if proper medical equipment were used; the failure to provide such care, leading to death hours later, was discussed in terms of whether treatment would have prevented death "within a short period" and offered a "possibility of survival." If the legal standard for the "avoided result" is framed not as guaranteed ultimate survival but as a significant chance of continued life, even if temporary, this could influence how stringently the probability of avoidance needs to be proven.

This line of reasoning connects to broader legal theories of causation, such as "risk increase" or "chance reduction." From this perspective, a defendant's omission could be seen as causal if it significantly increased the risk of the prohibited harm occurring or substantially reduced the victim's chances of avoiding that harm, even if it cannot be proven with absolute certainty that the harm would have been completely averted by the defendant's action. The Supreme Court's acceptance of an "eight or nine out of ten" chance of survival in I's case might be interpreted by some as aligning with a focus on a substantial alteration of risk attributable to the defendant's inaction.

IX. Concluding Thoughts: Omissions, Certainty, and the Boundaries of Criminal Responsibility

The Supreme Court's 1989 decision in the case of I and A provides a significant, though debated, marker in Japanese criminal law for assessing causation in offenses of omission resulting in death. It illustrates the judiciary's task of forging a workable legal standard when an individual's failure to act, in breach of a legal duty, is followed by a tragic and preventable outcome.

The "eight or nine out of ten" probability, deemed "certain to a degree that surpasses reasonable doubt," highlights the Court's attempt to quantify a threshold for this hypothetical causal link. It underscores that while absolute, 100% certainty of outcome-avoidance is not mandated, a very high degree of probability is necessary. The decision also implicitly emphasizes the profound legal responsibility that can fall upon individuals, particularly when they have created a dangerous situation for another (as I did by administering stimulants) or stand in a special protective relationship to them, and then fail to take necessary actions to avert foreseeable harm. The case serves as a stark reminder of the severe consequences that can flow from inaction when a duty to act is clear and another's life hangs in the balance.