Caught in the Middle: When a Head Lease Fails, What Happens to the (Approved) Sub-Lease in Japan?

Date of Judgment: February 25, 1997

Case Name: Claim for Building Rent, etc. (Main Suit); Counterclaim for Return of Security Deposit

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

Introduction

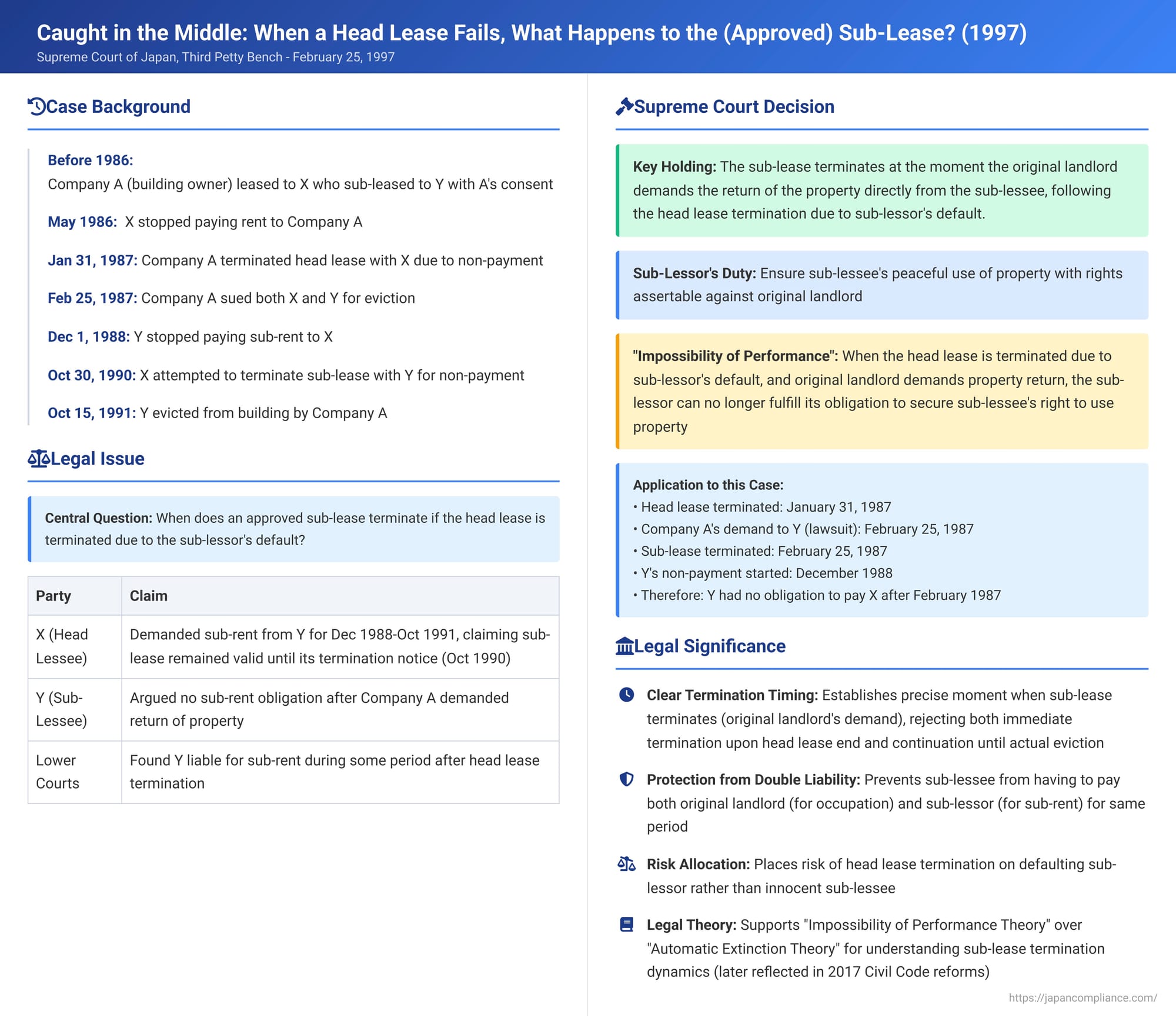

In complex commercial leasing arrangements, sub-leases are common. However, the position of a sub-tenant can become precarious if their direct landlord (the head lessee) defaults on their obligations to the original property owner, leading to the termination of the main (or "head") lease. A key question that arises is: what happens to the sub-lease, even if it was approved by the original property owner? A Japanese Supreme Court decision on February 25, 1997, provided crucial clarification on when such an approved sub-lease terminates and the extent of the sub-tenant's obligations.

The Layered Lease Structure and its Collapse

The dispute unfolded through the following sequence of events:

- The Parties and the Leases:

- Company A: The owner of a commercial building (the "Subject Building").

- X (King Kabushiki Kaisha): X leased the Subject Building from Company A (the head lease). X then renovated the building into a swimming facility.

- Y (Koma Sports K.K. and an affiliate, collectively "Y"): X entered into what was effectively a sub-lease agreement with Y, allowing Y to operate a swimming school in the Subject Building. This sub-lease had the consent of Company A, the original building owner.

- Default and Termination of Head Lease: X, the head lessee, defaulted on its rent payments to Company A from May 1986. Consequently, on January 31, 1987, Company A terminated the head lease agreement with X due to this non-payment.

- Eviction Proceedings by Original Landlord: On February 25, 1987, Company A initiated a lawsuit against both X (the head lessee) and Y (the sub-lessees) demanding that they vacate the Subject Building.

- Sub-Lessee Stops Paying Sub-Rent: From December 1, 1988 – notably, after Company A had sued them for eviction – Y stopped paying sub-lease rent to X.

- Purported Termination of Sub-Lease by Sub-Lessor: On October 30, 1990, X (the sub-lessor) attempted to terminate its sub-lease agreement with Y, citing Y's non-payment of the sub-rent.

- Actual Eviction: The lawsuit by Company A eventually succeeded. On June 12, 1991, a court order for eviction was issued against Y, which became final. Company A enforced this judgment, and Y was physically evicted from the Subject Building on October 15, 1991.

- Sub-Lessor Sues Sub-Lessee: X then sued Y, primarily seeking:

- Payment of unpaid sub-rent from December 1, 1988, up to X's purported termination of the sub-lease on October 30, 1990.

- Damages equivalent to the sub-rent for the period from X's purported termination until Y's actual eviction by Company A on October 15, 1991.

X also made an alternative claim for unjust enrichment for the same total amount.

- Lower Court Rulings: The first and second instance courts partially found in favor of X, holding Y liable for some portion of the claimed sub-rent/damages. Y appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Definitive Ruling

The Supreme Court, on February 25, 1997, overturned the lower courts' judgments that had favored X. It dismissed X's claims against Y entirely.

The Court's core reasoning was as follows:

- Essence of an Approved Sub-Lease: In a sub-lease approved by the original landlord, the sub-lessee's right to use and occupy the property must be a right that can be asserted against that original landlord. This is the fundamental protection an approved sub-lease offers.

- Sub-Lessor's Duty: The sub-lessor (X) has a primary contractual duty to the sub-lessee (Y) to ensure that Y can peacefully use and benefit from the property.

- Breach of Duty by Sub-Lessor: When the sub-lessor (X), through its own default (like non-payment of head lease rent to Company A), causes the head lease to be terminated, and as a result, the sub-lessee (Y) can no longer assert its sub-lease rights against the original landlord (Company A), the sub-lessor has fundamentally breached its duty to the sub-lessee.

- Consequences of Original Landlord's Demand on Sub-Lessee:

- Once the head lease is terminated due to the sub-lessor's default, and the original landlord (Company A) directly demands that the sub-lessee (Y) return the property, several legal consequences arise:

- The sub-lessee (Y) becomes obligated to return the property to the original landlord (Company A).

- For any continued use of the property from, at the latest, the time of this demand until actual vacation, the sub-lessee (Y) becomes liable directly to the original landlord (Company A) for damages (under tort principles) or for unjust enrichment.

- Impossibility of Sub-Lessor's Performance: Crucially, once the original landlord has made such a direct demand on the sub-lessee, it is no longer realistic to expect the sub-lessor (X) to somehow remedy the situation and restore the sub-lessee's (Y's) ability to lawfully occupy the premises against Company A (e.g., by X quickly re-establishing a new head lease with Company A). At this juncture, the sub-lessor's obligation to allow the sub-lessee to use the property effectively becomes impossible to perform (履行不能 - rikō funō), judged by societal common sense and business norms.

- Once the head lease is terminated due to the sub-lessor's default, and the original landlord (Company A) directly demands that the sub-lessee (Y) return the property, several legal consequences arise:

- Termination of the Sub-Lease: Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded: When a head lease is terminated due to the sub-lessor's default, an approved sub-lease will, as a general rule, terminate at the moment the original landlord demands the return of the property directly from the sub-lessee. This termination occurs due to the sub-lessor's impossibility of performing its core obligations to the sub-lessee.

- Application to the Facts:

- The head lease between Company A and X was terminated on January 31, 1987, due to X's rent default.

- Company A filed an eviction lawsuit against Y (the sub-lessees) on February 25, 1987. This lawsuit constituted a formal demand for the return of the property.

- Thus, the sub-lease between X and Y had already terminated by February 25, 1987, due to X's impossibility of performance.

- Consequently, X's claim against Y for sub-rent payments from December 1, 1988, onwards was unfounded because the sub-lease agreement (and Y's obligation to pay sub-rent to X) no longer existed by that date. X's alternative claim for unjust enrichment against Y was also dismissed, presumably because any benefit Y derived from occupying the premises after Company A's demand would be owed to Company A, not to X.

Untangling the Legal Relationships: Further Analysis

This Supreme Court decision helps clarify the distinct legal relationships and the timing of their unraveling.

Original Landlord (A) vs. Sub-Lessee (Y)

When the head lease is validly terminated, the sub-lessee's right to occupy the property, which is derived from the head lessee's rights, loses its legal foundation against the original landlord. The original landlord can then directly pursue eviction against the sub-lessee. As the Supreme Court noted, once the original landlord demands the return of the property, the sub-lessee's continued occupation can lead to liability for damages or unjust enrichment owed to the original landlord. Legal commentary suggests that, prior to such a demand, if the sub-lessee was unaware of the head lease termination, they might be considered a "good faith possessor" and potentially not liable to the original landlord for usage fees during that specific interim period.

Sub-Lessor (X) vs. Sub-Lessee (Y) – The Core of the Judgment

The termination of the sub-lease agreement itself was the central issue for X's claim against Y.

- Prevailing "Impossibility of Performance" Theory: While an old theory suggested a sub-lease automatically ends with the head lease (the "Automatic Extinction Theory"), modern Japanese legal thought, and this Supreme Court judgment, leans towards the "Impossibility of Performance Theory." This theory posits that the sub-lessor's primary duty is to enable the sub-lessee to use the property. If the head lease collapses due to the sub-lessor's fault, this duty becomes impossible.

- When Does Impossibility (and thus Sub-Lease Termination) Occur? There were several views:

- At the moment the head lease is terminated.

- At the moment the original landlord demands the return of the property from the sub-lessee. (This is the Supreme Court's adopted position.)

- At the moment the sub-lessee actually vacates or loses use of the property. (This was the approach of the lower courts in this case, which the Supreme Court rejected.)

- Rationale for the Supreme Court's Timing: The Court chose the moment of the original landlord's demand on the sub-lessee as the trigger for the sub-lease's termination because, at that point, any realistic prospect of the sub-lessor salvaging the situation and restoring the sub-lessee's rights vanishes. This approach also prevents the inequitable scenario where a sub-lessee might face double liability (to the original landlord for use/occupation and to the sub-lessor for sub-rent for the same period) or where the sub-lessor is unjustly enriched by collecting sub-rent for a period during which they cannot provide a legitimate right of occupancy assertable against the original landlord.

- Automatic Termination vs. Right to Terminate: The judgment implies that this impossibility of performance leads to an automatic termination of the sub-lease. It doesn't merely give the sub-lessee a right to actively terminate. This aligns with developments in Japanese contract law (codified in the 2017 Civil Code reforms, e.g., Article 616-2, reflecting prior case law) where certain types of impossibility in lease agreements are treated as direct causes of termination.

A Note on Investment Recovery

In this specific case, X (the sub-lessor) had invested in converting the building into a swimming facility, which likely allowed X to charge Y a sub-rent higher than the head rent X owed to Company A. Some legal arguments in similar contexts suggest that allowing a sub-lease to continue for as long as the sub-lessee actually uses the property might enable a sub-lessor to recoup such investments. However, the Supreme Court's stance (and related legal commentary) generally indicates that recovery of capital investments made in leased property should typically be pursued through statutory mechanisms, such as a claim for reimbursement of beneficial expenses (有益費償還請求権 - yūekihi shōkan seikyūken) against the party who ultimately benefits from those improvements (often the original landlord), rather than by artificially prolonging a sub-lease that has fundamentally lost its legal basis.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1997 decision provides clear and significant guidance for a common but complex scenario in commercial leasing. It establishes that an approved sub-lease terminates due to the sub-lessor's impossibility of performance at the point when the original landlord, having already terminated the head lease due to the sub-lessor's default, makes a direct demand upon the sub-lessee for the return of the property. From this moment, the sub-lessee's obligation to pay sub-rent to the defaulting sub-lessor ceases. This ruling emphasizes the derivative nature of sub-lease rights and allocates risks in a manner that aims to prevent unjust enrichment and double liability, while marking a clear end-point for the sub-lease relationship when its foundation collapses due to the sub-lessor’s failure.