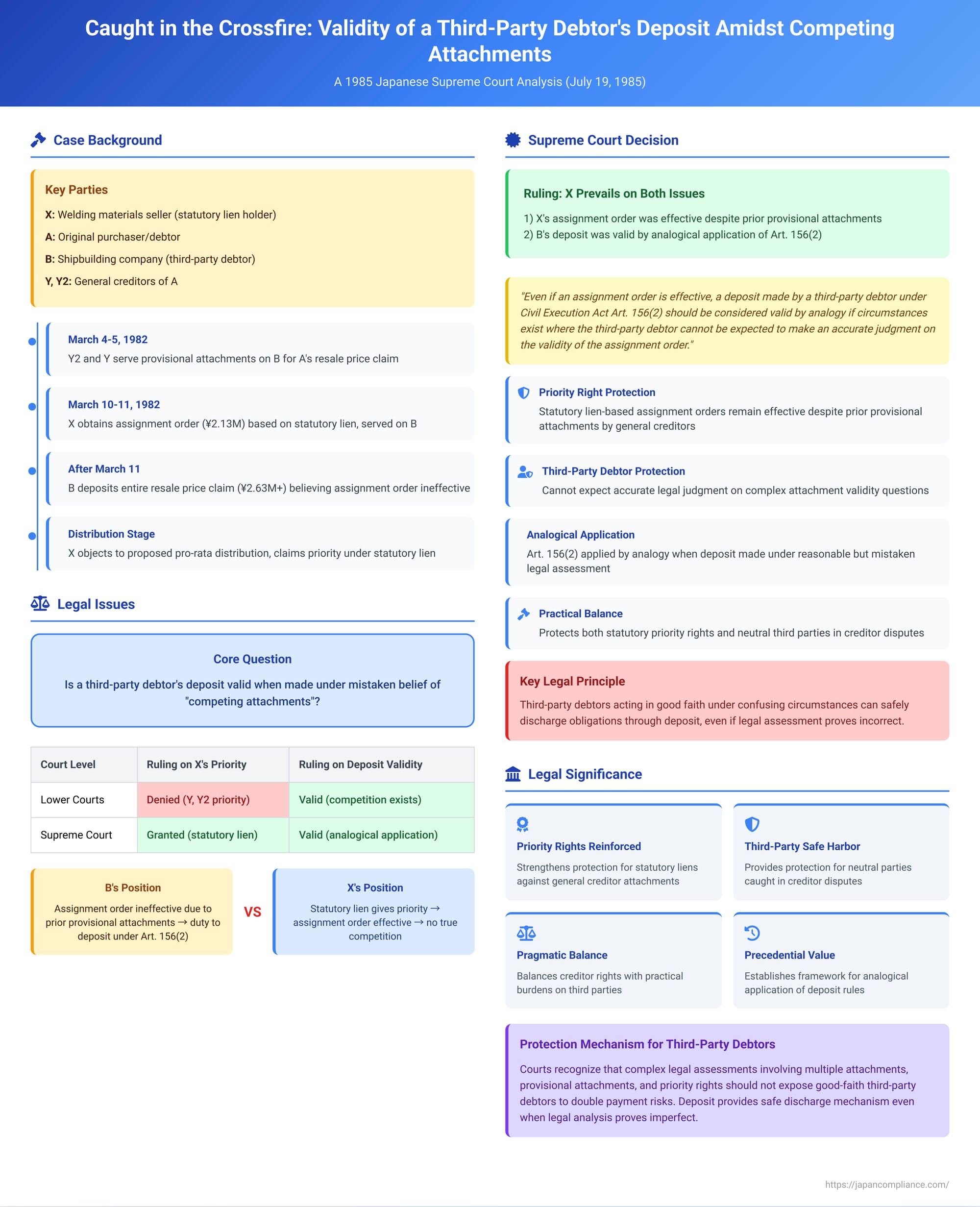

Caught in the Crossfire: Validity of a Third-Party Debtor's Deposit Amidst Competing Attachments – A 1985 Japanese Supreme Court Analysis

Date of Judgment: July 19, 1985

Case Name: Distribution Objection Case

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

Case Number: 1983 (O) No. 1548

Introduction

Imagine being a company (a "third-party debtor") that owes money to another business. Suddenly, you're bombarded with court orders from various creditors of that business, each trying to seize the funds you owe. One creditor might have a provisional attachment, another a final attachment, and yet another might present an "assignment order" claiming direct ownership of the debt. Navigating this legal minefield is fraught with peril; paying the wrong party or mishandling the situation can lead to being forced to pay twice. In such complex scenarios, when can a third-party debtor safely discharge their obligation by depositing the owed amount with the court?

The Japanese Supreme Court's decision on July 19, 1985, provides crucial guidance on this issue, particularly concerning the validity of a deposit made by a third-party debtor who reasonably, but perhaps not with perfect legal accuracy, perceives a "competition of attachments." This case highlights the balance between protecting diligent creditors and safeguarding third-party debtors caught in the procedural crossfire.

The Factual Vortex: A Statutory Lien, an Assignment Order, and Competing Provisional Attachments

The case involved several parties and a complex series of events:

- X (Plaintiff/Appellant): A company that sold welding materials to A.

- A (Debtor): The original purchaser of the welding materials from X.

- B (Third-Party Debtor): A shipbuilding company that purchased the welding materials from A.

- Y and Y2 (Defendants/Appellees): General creditors of A.

Here’s how the situation unfolded:

- X's Initial Claim and Statutory Lien: X was owed over JPY 2.13 million by A for welding materials. A subsequently resold these materials to B for a sum exceeding JPY 2.63 million (referred to as the "Resale Price Claim"). Under Japanese law (Civil Code Art. 304(1)), a seller of movables can have a statutory lien (動産売買先取特権, dōsan baibai sakidori tokken) on the price if the goods are resold. This lien can be exercised against the resale price payable by the third-party purchaser (B) through a process known as "subrogation to proceeds" or "object dation" (物上代位, butsujō daii).

- X's Assignment Order: Exercising this statutory lien, X obtained a court-issued attachment order and, importantly, an assignment order (転付命令, tenpu meirei) on March 10, 1982. This assignment order transferred over JPY 2.13 million of A's Resale Price Claim (owed by B) directly to X. These orders were served on B on March 11, 1982, and the assignment order later became final and binding.

- Prior Provisional Attachments by Y, Y2, and X: Before X's assignment order was served, several provisional attachment orders had already been served on B concerning A's Resale Price Claim:

- Y had a provisional attachment for a claim of over JPY 6.06 million against A, served on B on March 5, 1982.

- Y2 had a provisional attachment for a claim of over JPY 2.29 million against A, served on B on March 4, 1982.

- X itself also had an earlier provisional attachment (for a different sales credit claim of JPY 500,000 against A), served on B on March 5, 1982.

- B's Deposit with the Court: Faced with these various orders, B (the third-party debtor) formed the view that X's assignment order was likely ineffective. This was because Article 159(3) of the Civil Execution Act generally renders an assignment order ineffective if, by the time it's served on the third-party debtor, other creditors have already executed attachments, provisional attachments, or made demands for distribution. Believing there was a "competition of attachments" (差押えの競合, sashiosae no kyōgō), B decided to deposit the entire amount of the Resale Price Claim (over JPY 2.63 million) with the competent legal affairs bureau (acting as a depository for the court). B cited this perceived competition as the basis for the deposit, intending to invoke Civil Execution Act Art. 156(2), which obliges a third-party debtor to make such a deposit under certain conditions of competing claims. B duly notified the execution court of this deposit.

- The Execution Court's Initial Distribution Plan: The execution court, apparently sharing B's view that X's assignment order was ineffective due to the prior provisional attachments by Y and Y2, prepared a distribution table (配当表, haitō-hyō). This table proposed to distribute the deposited funds (after deducting procedural costs) proportionally among X (presumably for its JPY 500,000 provisional attachment) and Y and Y2, based on their respective claim amounts. X's larger claim, purportedly secured by the assignment order, was not given priority.

- X's Lawsuit (Distribution Objection): X disagreed strongly, arguing that its assignment order, rooted in a statutory lien, was effective and granted it priority. X filed a lawsuit objecting to the proposed distribution, seeking to have the JPY 2.13 million covered by its assignment order paid out to it preferentially.

The lower courts sided against X, holding that its statutory lien could not be asserted against Y and Y2 because their provisional attachments were served first. X appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Twin Pronouncements

The Supreme Court, in its judgment of July 19, 1985, overturned the lower courts' decisions and ruled entirely in favor of X. The judgment had two critical components:

- Effectiveness of X's Assignment Order (The Priority Issue):

The Court first clarified a vital point regarding X's assignment order. It held that an assignment order obtained by a creditor exercising a statutory lien on movables through subrogation to proceeds (like X did) is indeed effective, even if it is served on the third-party debtor (B) after other general creditors (like Y and Y2) have served provisional attachment orders. This means the general rule in Civil Execution Act Art. 159(3) (which would invalidate an assignment order in such circumstances) does not apply when the assignment order is based on such a pre-existing priority right. X, therefore, had a valid and prior claim to the JPY 2.13 million portion of the Resale Price Claim. - Validity of B's Deposit with the Court (The Focus of this Analysis):

Despite finding X's assignment order fully effective (meaning there wasn't truly a "competition of attachments" regarding the JPY 2.13 million that would oblige B to deposit that portion under Art. 156(2)), the Supreme Court nevertheless held that B's deposit of the entire sum was valid.

The Court's reasoning for upholding the deposit was based on an analogical application of Civil Execution Act Art. 156(2). It stated:

"Even if an assignment order is effective, and thus legally there is no competition of attachments, a deposit made by a third-party debtor under Civil Execution Act Art. 156(2) should be considered valid by analogy if circumstances exist where the third-party debtor cannot be expected to make an accurate judgment on the validity of the assignment order."In B's specific situation, X's assignment order was served after Y and Y2's provisional attachments. The Supreme Court recognized that it would be "difficult to expect the third-party debtor (B) to make an accurate judgment" on the complex legal question of whether X's assignment order was valid despite the prior provisional attachments (i.e., to know about the special exception for statutory lien-based assignments). Therefore, B’s deposit, made under the reasonable (though ultimately mistaken) belief that X's assignment was ineffective and that there was a full competition of attachments, was deemed valid.

Deep Dive into the Validity of the Third-Party Debtor's Deposit

The Supreme Court's decision to validate B's deposit, even when X's assignment order was effective, hinges on protecting the third-party debtor placed in a perplexing situation.

General Rules for Deposits by Third-Party Debtors:

The Civil Execution Act provides two main scenarios for deposits:

- Permissive Deposit (Art. 156(1)): A third-party debtor has the right (but not a duty) to deposit the owed amount with the court if any attachment order (including one underlying a later assignment order) is served on them. This allows the third-party debtor to discharge their liability and avoid complications arising from the payment prohibition that an attachment imposes (Art. 145(1)).

- Obligatory Deposit (Art. 156(2)): A third-party debtor has a duty to deposit the owed amount if multiple final attachments are served, or if a combination of attachments and demands for distribution occurs, and the total sum of these claims exceeds the debt owed by the third-party debtor (or if the claims are for non-monetary assets that cannot be divided). This is a true "competition of attachments" that necessitates a formal distribution process by the court.

- Importantly, as legal commentary points out, provisional attachments alone, even if numerous and exceeding the debt, generally do not trigger the duty to deposit under Art. 156(2). This section is primarily concerned with competing final claims that require immediate distribution.

Why B's Situation Didn't Strictly Mandate Deposit (for the full sum under Art. 156(2)):

Once the Supreme Court determined that X's assignment order for JPY 2.13 million was effective, that portion of the Resale Price Claim was legally transferred to X. It was no longer A's asset and thus not available to A's general creditors (Y and Y2). Therefore, regarding this JPY 2.13 million, there was no "competition of attachments" that would oblige B to deposit it under Art. 156(2). The remaining portion of the Resale Price Claim (around JPY 500,000) was subject to competing provisional attachments by X, Y, and Y2, but as noted, this alone wouldn't typically create a duty to deposit under Art. 156(2).

The "Analogical Application" and Protection of the Third-Party Debtor:

The Supreme Court validated B's deposit by analogously applying Art. 156(2). The rationale was:

- Difficulty of Accurate Judgment: The legal landscape involving multiple attachments, provisional attachments, and an assignment order based on a nuanced priority right (statutory lien) is complex. B, as a third-party debtor, could not reasonably be expected to possess the legal expertise to definitively determine whether X's assignment order was valid despite the earlier provisional attachments by Y and Y2. B's assumption that the assignment order was ineffective under the general rule of Art. 159(3) was understandable, even if incorrect in this specific, exceptional circumstance.

- Preventing Undue Burden: Forcing third-party debtors to make such intricate legal assessments at their own peril would place an excessive burden on them. The deposit system is partly designed to allow them to extricate themselves safely from creditor disputes.

This pragmatic approach has received broad support from legal scholars.

Historical Parallels:

This line of reasoning—protecting a third-party debtor who makes a deposit based on a reasonable but legally imperfect understanding of a complex attachment scenario—is not entirely new.

- Under the old Code of Civil Procedure, a Supreme Court decision on December 15, 1970, addressed a situation where a third-party debtor deposited funds even though the conditions for a mandatory deposit were not strictly met (the total attached claims did not exceed the debt). The Court held that if a third-party debtor faced numerous attachments and found it objectively difficult to ascertain their validity or priority, a deposit made by them could be deemed valid by analogy, thereby granting them a discharge from liability.

- The 1985 judgment aligns with this philosophy of providing a safe harbor for third-party debtors acting in good faith under confusing circumstances.

Alternative Justification for the Deposit's Validity (Art. 156(1)):

Legal commentary suggests that B's deposit could also have been recognized as valid under the permissive deposit rule of Art. 156(1) of the Civil Execution Act.

- This provision allows a third-party debtor to deposit the funds if any attachment order is served. X's initial attachment order (which formed the basis of the assignment order) would qualify. B could have made the deposit under this provision to avoid potential liability for non-payment while the legal effects of the various orders were sorted out.

- Even if B made the deposit after X's assignment order had become final, deposit-taking offices in practice often accept such deposits unless the finality of the assignment order is unequivocally clear from the third-party debtor's deposit application. This is because third-party debtors are not always in a position to definitively know if an assignment order is final and unappealable, and it's considered unreasonable to burden them with an extensive duty to investigate this.

Implications for Distribution of the Deposited Funds

Since the Supreme Court found X's assignment order effective and B's deposit of the entire sum valid, the execution court would need to carry out formal distribution proceedings (配当手続, haitō tetsuzuki) as stipulated in Civil Execution Act Art. 166(1)(i).

The outcome of the distribution would be:

- The JPY 2.13 million covered by X's valid assignment order would be allocated to X due to its priority.

- The remaining balance of the deposited funds (approximately JPY 500,000 from the Resale Price Claim, less any procedural costs) would then be distributed proportionally among X (for its separate JPY 500,000 provisional attachment) and Y and Y2 (for their respective provisional attachments).

Procedurally, the execution court would typically require X to submit documentary proof of its attachment order and the finality of its assignment order. Based on this, the court would then prepare a revised distribution table reflecting X's priority.

Debate on Handling Assigned Funds Within Distribution:

There's some academic debate on how funds subject to an effective assignment order should be handled when a full deposit has been made:

- One perspective is that the assignee (X) should be able to claim their assigned portion directly from the deposited funds (e.g., through a request for refund of deposited money for that specific amount), without that portion being subjected to the formal distribution voting and objection process applicable to general creditors. Only the remainder would go through full distribution.

- Another view, which seems to be implicitly supported by the Supreme Court's approach in this and similar cases, is that the execution court should generally initiate distribution proceedings for the entire deposited sum. The court makes a preliminary assessment of the assignment order's validity and includes the assignee in the distribution table according to their priority. Any disagreements among creditors (e.g., if Y or Y2 still contested X's priority despite the Supreme Court's ruling on the legal principle) would then be resolved through formal objections within the distribution procedure or through separate lawsuits.

Broader Significance and Conclusion

The Supreme Court's July 19, 1985, decision serves as a vital precedent. It underscores the robust protection afforded to certain priority rights, such as those stemming from statutory liens, allowing them to prevail even when an assignment order is served after other provisional attachments. More centrally to this analysis, the judgment significantly reinforces the protection available to third-party debtors caught in the web of competing creditor claims.

By validating a deposit made due to a reasonable, albeit legally imperfect, assessment of a complex situation involving competing attachments and an assignment order of uncertain immediate effect, the Court acknowledged the practical difficulties faced by such parties. The "analogical application" of deposit rules in such circumstances allows third-party debtors to discharge their obligations safely and avoid the risk of double payment, without needing to be infallible legal experts. This decision strikes a pragmatic balance: ensuring the efficacy of priority rights in debt execution while also providing a necessary shield for neutral third parties ensnared in creditor disputes.