Casting a Wide Net: Japan's Supreme Court on the Reach of Prefectural Fishing Rules

A First Petty Bench Ruling from April 22, 1971

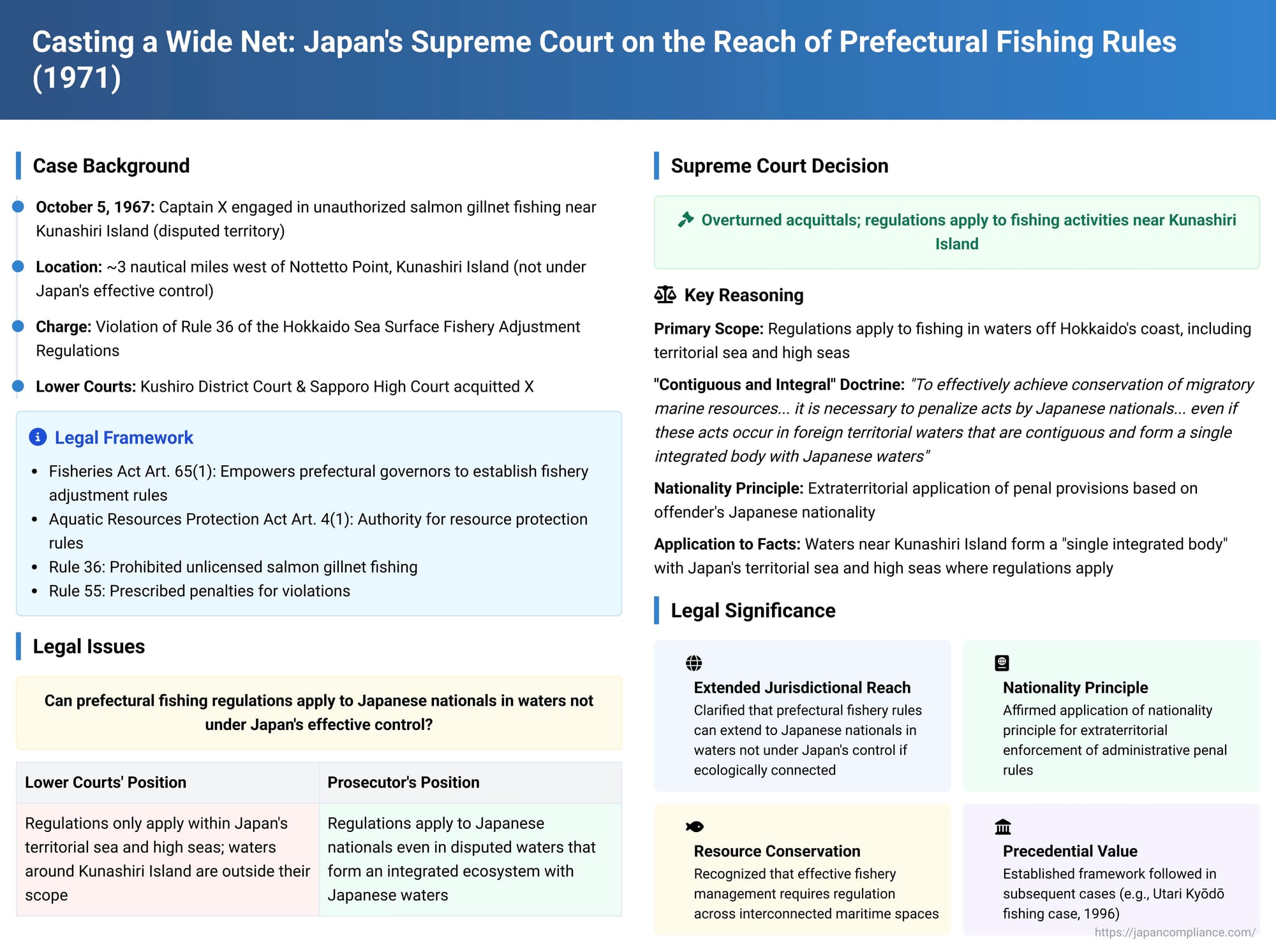

Regulating activities like fishing, which often occur across or near maritime boundaries, presents complex legal challenges regarding the geographical reach of domestic laws and regulations. A key Japanese Supreme Court decision from its First Petty Bench on April 22, 1971 (Showa 44 (A) No. 2736), addressed such a challenge, clarifying the extent to which a Hokkaido prefectural fishery regulation could apply to the actions of a Japanese national. The case specifically concerned fishing activities conducted in waters near Kunashiri Island, one of the Northern Territories administered by Russia but claimed by Japan, raising questions about the applicability of Japanese rules in areas not under Japan's effective administrative control.

The Case of X and the Salmon Gillnet

The defendant, X, was the captain and fishing master of a vessel named the No. 12 Sanko Maru. On October 5, 1967, he was engaged in salmon gillnet fishing (さけ刺し網漁業 - sake sashi-ami gyogyō) in a sea area approximately three nautical miles west of Nottetto Point (ノッテット崎 - Nottetto-saki) on Kunashiri Island (国後島 - Kunashiri-tō). X did not possess a fishing right or license authorizing this specific activity in that area. At that time, Japan's declared territorial sea extended to three nautical miles from its coastline (it has since been extended to twelve nautical miles).

X was subsequently charged with violating Rule 36 of the Hokkaido Sea Surface Fishery Adjustment Regulations (北海道海面漁業調整規則 - Hokkaidō Kaimen Gyogyō Chōsei Kisoku, hereinafter "the Hokkaido Regulations"). The core legal question was whether these prefectural regulations, designed to manage fisheries off the coast of Hokkaido, could be applied to fishing activities in the waters near Kunashiri Island, given the island's disputed status and lack of effective Japanese administrative control.

The Legal Framework: Fisheries Act, Resource Protection, and Prefectural Rules

The authority for the Hokkaido Regulations stemmed from national laws:

- The Fisheries Act (漁業法 - Gyogyō Hō, then Article 65, paragraph 1) empowered prefectural governors to establish rules for fishery adjustment.

- The Aquatic Resources Protection Act (水産資源保護法 - Suisan Shigen Hogo Hō, then Article 4, paragraph 1) provided similar authority for rules aimed at the protection and cultivation of aquatic resources.

Acting under these delegations, the Governor of Hokkaido had established the Hokkaido Regulations. Rule 36 of these regulations prohibited ten types of fishing, including salmon gillnet fishing, unless conducted under a specific fishing right or license. Rule 55, paragraph 1, prescribed penalties for violations of these prohibitions. (These specific regulations have since been superseded by new rules following revisions to the Fisheries Act ).

Lower Courts' Acquittals

The initial court proceedings resulted in acquittals for X:

- The Kushiro District Court (first instance) found X not guilty. It reasoned that the Hokkaido Regulations were generally intended to apply only within Japan's territorial sea and on the high seas. The territorial waters around Kunashiri Island, being under effective foreign administration despite Japan's territorial claim, were treated as analogous to foreign territorial waters for the purpose of the regulations' applicability and thus considered outside their scope. Furthermore, the prosecution had not definitively proven that X's fishing activities had occurred on the high seas beyond Kunashiri's three-nautical-mile limit.

- The Sapporo High Court (second instance) upheld the District Court's acquittal, largely endorsing its reasoning.

The public prosecutor appealed this decision to the Supreme Court, highlighting a conflicting precedent from the Sapporo High Court in a similar case (known as the "No. 8 Kitajima Maru case") where a guilty verdict had been rendered under comparable circumstances.

The Supreme Court's Decision of April 22, 1971

The Supreme Court overturned the acquittals by the lower courts and remanded the case back to the Kushiro District Court for retrial. The Court's judgment provided a significant interpretation of the geographical scope of such prefectural fishery regulations.

Core Reasoning on the Scope of Application:

- Primary Scope of the Regulations: The Court first established that Rule 36 of the Hokkaido Regulations, enacted under the authority of the Fisheries Act and the Aquatic Resources Protection Act, was primarily intended to apply to fishing activities in the sea areas off the coast of Hokkaido ("北海道地先海面" - Hokkaidō chisen kaimen). This includes areas where:

- Fishery adjustment measures and the protection and cultivation of aquatic resources are deemed necessary.

- The relevant Minister or the Governor of Hokkaido can effectively conduct fishery enforcement.

Within these geographical confines, the regulations naturally apply to: - Fishing activities conducted within Japan's territorial sea.

- Fishing activities conducted by Japanese nationals on the high seas.

- Extension to "Contiguous and Integral" Foreign or Disputed Waters: The Supreme Court then addressed the crucial issue of application in waters not under Japan's effective control but adjacent to its jurisdictional areas.

- It acknowledged that if a Japanese vessel engages in fishing within the territorial waters of a foreign state, Japan, as a general principle and in the absence of specific agreements, cannot exercise its enforcement powers (such as on-site inspections) within those foreign waters.

- However, the Court reasoned that to effectively achieve the objectives of the Fisheries Act, the Aquatic Resources Protection Act, and the Hokkaido Regulations—namely, the conservation of migratory marine resources and the maintenance of orderly fishing practices in the vast, borderless ocean—it is sometimes necessary to penalize acts by Japanese nationals that violate rules like Rule 36, even if these acts occur in foreign territorial waters. This necessity arises particularly when such foreign territorial waters are "contiguous and form a single integrated body" (連接して一体をなす - rensetsu shite ittai o nasu) with the Japanese territorial sea and the high seas where the regulations clearly apply.

- Therefore, the Court interpreted Rule 36 (the fishing prohibition) and Rule 55 (the penalty provision) of the Hokkaido Regulations as being intended to apply to fishing activities undertaken by Japanese nationals in such contiguous foreign territorial waters.

- Specifically, Rule 55 was understood to authorize punishment for violations of Rule 36 committed by Japanese nationals not only within Japan's territorial sea and the relevant high seas but also in foreign territorial waters that are geographically and ecologically connected to these areas. This constitutes an instance of extraterritorial application of penal provisions based on the nationality of the offender (a concept related to 国外犯 - kokugaihan, or offenses committed outside national territory).

- Application to the Waters Near Kunashiri Island: Applying this interpretation to the facts of the case:

- The Court noted that although Japan currently does not exercise effective administrative control over Kunashiri Island (meaning the Hokkaido Governor cannot issue licenses or conduct on-site inspections within its three-nautical-mile territorial sea), the specific sea area where X conducted his fishing activities does belong to the sea area that is contiguous and forms a single integrated body with Japan's territorial sea and the relevant high seas where Japanese regulations apply to its nationals.

- Consequently, the Supreme Court concluded that Rule 36 of the Hokkaido Regulations prohibits Japanese nationals from engaging in the listed unlicensed fishing activities in this specific area near Kunashiri Island, and violators are subject to penalties under Rule 55.

The lower courts had therefore erred in their interpretation and application of the law by concluding that X could not be held culpable.

Understanding Territoriality and Extraterritoriality in Japanese Law

This decision touches upon fundamental principles of how laws apply geographically:

- Territoriality Principle (属地主義 - zokuchi shugi): This is the general rule that a state's laws apply within its own territory (its land, territorial sea, and airspace).

- Nationality Principle (属人主義 - zokujin shugi): This principle allows a state to apply its laws to its own nationals, regardless of where they commit an act. While the Japanese Penal Code has specific provisions for certain crimes committed by Japanese nationals abroad, the application of administrative penal laws (like fishery regulations) extraterritorially based on nationality is less common and generally requires clear justification.

- Extraterritorial Application of Administrative Law: The commentary accompanying the case notes that explicit provisions for the extraterritorial application of Japanese administrative laws are limited, though examples exist (e.g., in foreign exchange and trade law). The permissibility of such application generally requires a balancing of factors, including the necessity for achieving the domestic law's purpose, the potential impact on foreign legal systems, and the foreseeability for the individuals concerned.

The Supreme Court, in this case, justified the extraterritorial application of the Hokkaido fishery regulations to a Japanese national based on the specific nature of fisheries (migratory resources in interconnected marine environments) and the overarching public interest in resource conservation and orderly fishing. The inability to conduct direct enforcement (like on-site inspections) in waters not under Japan's effective control was not seen as a bar to subsequent prosecution and punishment in Japan for violations committed there by its nationals.

Significance of the Ruling

The 1971 Supreme Court decision in this case is significant for several reasons:

- Clarification on Reach of Prefectural Fishery Rules: It established that prefectural fishery regulations, enacted under national enabling laws, can extend their reach to Japanese nationals operating in certain foreign territorial waters or disputed waters, provided those waters are contiguous and integral to areas where Japan does exercise jurisdiction.

- Affirmation of Nationality Principle in Administrative Penal Law: The ruling affirmed the application of the nationality principle for the extraterritorial enforcement of domestic administrative penal rules when deemed necessary to achieve the underlying legislative objectives, particularly in contexts like fisheries management where resources and activities transcend strict territorial lines.

- Distinction from Prior Approaches: Legal commentary points out that this approach, grounding extraterritoriality in the nationality principle for acts in foreign waters, differs from some earlier precedents which might have relied more on the "flag state" principle (treating acts on Japanese-flagged vessels as occurring within Japanese jurisdiction, a form of territoriality under Article 1, paragraph 2 of the Penal Code).

- Setting a Precedent: This judgment's reasoning regarding the extraterritorial application of fishery regulations to Japanese nationals was subsequently followed and reinforced in similar cases, such as the Utari Kyōdō fishing case decided by the Supreme Court in 1996, solidifying this as an established judicial interpretation in Japan. It demonstrates that while territoriality is the primary basis for legal jurisdiction, the nationality principle can be invoked for the application of Japanese administrative laws under specific circumstances, guided by the law's purpose, the nature of the regulated activity, and the interest being protected.

Broader Implications

This decision reflects a pragmatic judicial approach to regulatory jurisdiction in inherently transboundary contexts like fisheries management. It acknowledges that effective resource conservation and the maintenance of fishery order sometimes require a state to regulate the conduct of its own nationals even when they are operating in maritime areas beyond its direct enforcement capabilities. The commentary with the source material briefly touches upon the theoretical question of whether such logic could extend to non-nationals under certain doctrines (like the "effects doctrine" seen in competition law), but notes the significant international law and legal stability considerations that would make such an extension highly complex and necessitate extreme caution.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1971 ruling in the Hokkaido Sea Surface Fishery Adjustment Regulations case is a key decision in Japanese administrative law, particularly concerning the geographical application of domestic regulations. It clarifies how Japan balances the primary principle of territorial jurisdiction with the necessity of regulating its nationals' activities in interconnected maritime spaces to achieve important public policy goals like resource conservation and the maintenance of orderly fisheries. The concept of applying rules to nationals in "contiguous and integral" sea areas, even those not under Japan's effective administrative control, demonstrates a flexible approach tailored to the unique challenges of managing shared and migratory natural resources.