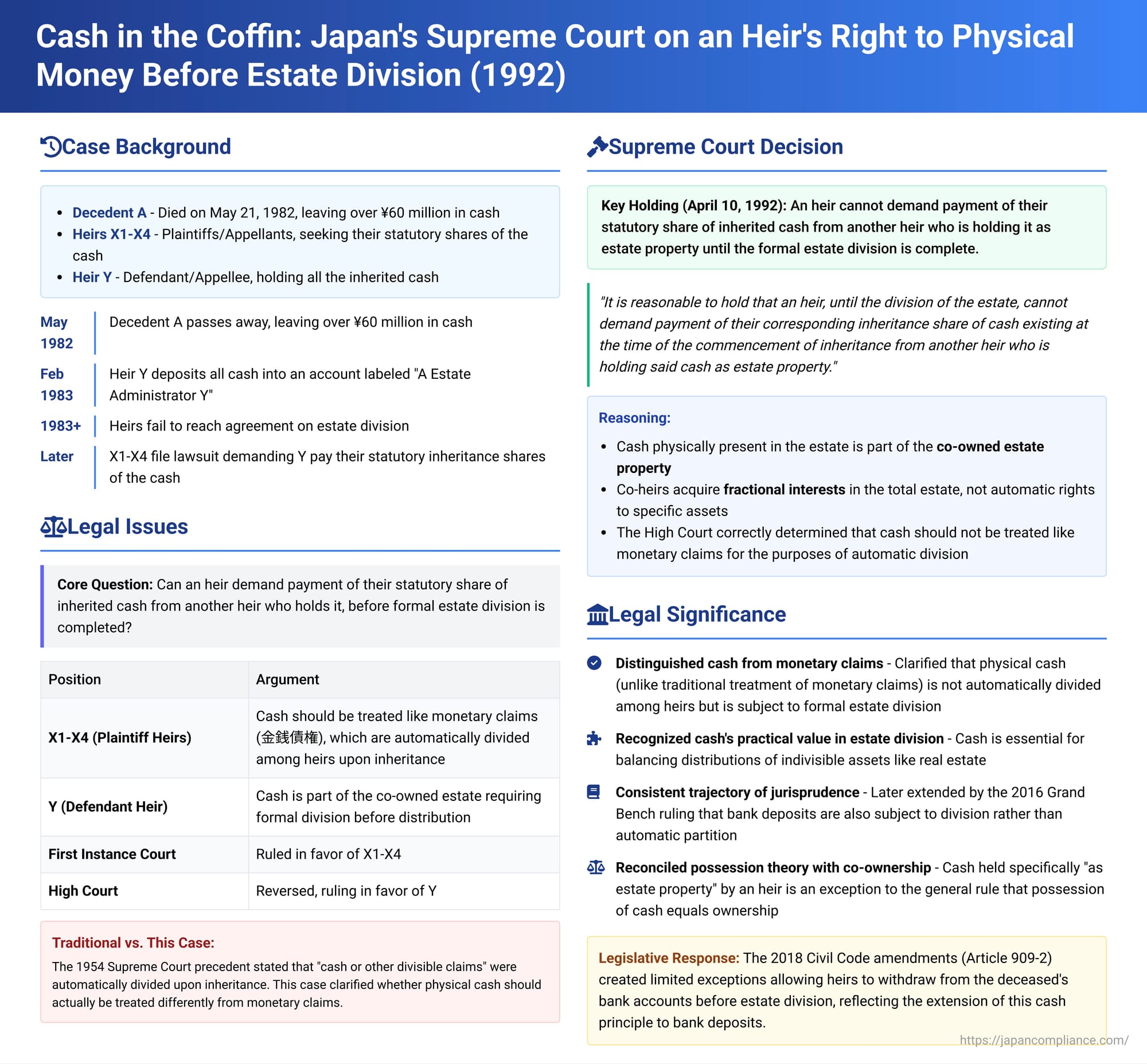

Cash in the Coffin: Japan's Supreme Court on an Heir's Right to Physical Money Before Estate Division

Date of Judgment: April 10, 1992

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench, Case Nos. Heisei 1 (o) No. 433, No. 602 (Claim for Return of Retained Money)

When an individual passes away leaving behind cash, a seemingly straightforward asset, its treatment within an undivided inherited estate can present complex legal questions. Is physical cash immediately divisible among heirs according to their statutory shares, similar to how certain monetary claims were traditionally viewed? Or does it form part of the collective co-owned estate, requiring formal division procedures? The Supreme Court of Japan addressed this issue directly in its decision on April 10, 1992, clarifying that physical cash belonging to an estate is subject to formal estate division and cannot be claimed by individual heirs based on their shares before such division is complete.

Facts of the Case

The dispute arose from the estate of A, who passed away on May 21, 1982, leaving behind more than 60 million yen in cash.

- The Heirs: The co-heirs of A were X1, X2, X3, and X4 (the plaintiffs/appellants) and Y (the defendant/appellee).

- Handling of the Cash: In February of the year following A's death, Y deposited the entirety of this cash into a bank account under the name "A Estate Administrator Y."

- The Dispute and Lawsuit: The co-heirs had not yet reached an agreement on the division of A's estate (遺産分割協議 - isan bunkatsu kyōgi). X1-X4 initiated a lawsuit against Y, claiming that Y was holding the estate's cash and demanding that Y pay them their respective statutory inheritance shares of this money.

- Lower Court Rulings:

- The court of first instance ruled in favor of X1-X4.

- However, the High Court (on appeal by Y) overturned this decision, ruling in favor of Y. The High Court reasoned that cash, like other movable and immovable properties, becomes the co-owned property of the heirs upon the deceased's death. Heirs acquire a fractional interest (持分権 - mochibunken) in the total estate, not an automatic right to a divided portion of specific assets like cash merely based on their statutory shares. It held that even if the cash was subsequently deposited into a bank account, this did not retroactively transform it into a divisible monetary claim from the moment of death for the purpose of immediate distribution. Therefore, since the estate division was still pending, X1-X4 could not demand their shares of the cash.

- Appellants' Arguments to the Supreme Court: X1-X4 appealed to the Supreme Court. They argued that the High Court's decision created an imbalance with established case law concerning monetary claims (which were generally considered automatically divided among heirs upon inheritance). They further contended that physical cash is easily divisible and possesses characteristics distinct from other movable and immovable assets, warranting different treatment.

The Supreme Court's Decision

The Supreme Court dismissed the appeal by X1-X4.

The Court succinctly stated its core principle:

"It is reasonable to hold that an heir, until the division of the estate, cannot demand payment of their corresponding inheritance share of cash existing at the time of the commencement of inheritance from another heir who is holding said cash as estate property."

Applying this principle, the Court found that X1-X4 were demanding their shares of estate cash held by Y before the estate division was complete. The Supreme Court affirmed the High Court's judgment that X1-X4's claim was unfounded, finding no error in its reasoning.

Legal Background and Commentary

The brevity of the Supreme Court's direct reasoning in this case belies the complex legal principles at play. The accompanying legal commentary provides essential context:

1. Fundamental Principles of Japanese Inheritance Law:

To understand the 1992 decision, several background points from Japanese case law are crucial:

* Nature of Estate Co-ownership: The co-ownership of inherited property by multiple heirs (as stipulated in Article 898 of the Civil Code) is generally considered to be no different in its fundamental nature from ordinary co-ownership (as defined in Article 249 et seq. of the Civil Code).

* Divisible Monetary Claims (Traditional View): A long-standing Supreme Court precedent (Showa 29.4.8 - April 8, 1954) established that if an inherited estate includes "cash or other divisible claims" (金銭その他の可分債権 - kinsen sonota no kabun saiken), such claims are automatically divided by law upon inheritance, with each co-heir succeeding to their respective share. If a co-heir collected more than their share, they would be liable to other heirs for unjust enrichment or tort.

* Estate Division Procedure: The division of an inherited estate among co-heirs, if not settled by agreement, is determined by the Family Court through an adjudication process (審判 - shinpan), not by a civil court lawsuit for partition of co-owned property (as per Article 258 of the Civil Code, which applies to ordinary co-ownership disputes).

* Ownership of Cash (Possession Theory): There's a prevailing theory in Japanese law that, in the absence of "special circumstances" (特段の事情 - tokudan no jijō), the owner of physical cash is presumed to be the person who possesses it, irrespective of the legitimacy of that possession.

2. Cash vs. Monetary Claims: A Key Distinction:

The 1992 Supreme Court judgment implicitly clarifies a crucial point regarding the Showa 29 precedent. By ruling that physical cash within an estate is not automatically divided but is subject to formal estate division, the Court effectively signaled that the phrase "cash or other divisible claims" in the older precedent should be interpreted as "monetary claims or other divisible claims." This means that physical cash held by the deceased at the time of death is treated differently from, for example, a bank deposit owed to the deceased by a financial institution (which would be a monetary claim). The former becomes part of the co-owned pool of estate assets requiring division; the latter, under the traditional view, was seen as automatically partitioning.

The Supreme Court, in choosing to align the treatment of physical cash with other non-divisible assets like real estate rather than with monetary claims, made a significant choice. The commentary suggests strong grounds for this:

* The easy divisibility of cash is not a sufficient reason to treat it exceptionally. Other assets, like a quantity of rice, are also easily divisible but are undisputed subjects of formal estate division.

* Monetary claims involve a third-party debtor, adding complexity. Physical cash, however, is primarily an internal matter among co-heirs.

* Crucially, in practical estate division negotiations, cash is an extremely useful asset for adjusting imbalances that arise from the division of indivisible properties (like real estate). If cash were deemed automatically divided, it would significantly complicate and hinder the flexibility needed for effective estate division agreements.

3. Reconciling Co-ownership of Cash with the Possession Theory:

A theoretical challenge arises: if cash is co-owned by the heirs, how does this square with the principle that the possessor of cash is generally its owner, especially when one heir (Y, in this case) is holding all of it?

The commentary suggests that the Supreme Court's phrasing "cash existing at the time of the commencement of inheritance held by another heir as estate property" (相続財産として保管している) provides the key. This situation is likely considered one of the "special circumstances" that acts as an exception to the general cash-possession-equals-ownership rule. When an heir holds cash in a custodial capacity for the benefit of the estate, and it's not intended for general circulation by that heir but is being preserved, their possession does not automatically translate into sole ownership. This aligns with academic theories distinguishing custodial holding of money from money in general circulation.

4. Evolution of Case Law and the 1992 Judgment's Place:

The legal landscape concerning divisible assets in inheritance has continued to evolve since this 1992 decision. The PDF commentary highlights a landmark Supreme Court Grand Bench decision from Heisei 28.12.19 (December 19, 2016). This later ruling overturned the traditional view for certain types of monetary claims, holding that ordinary bank deposits (普通預金債権 - futsū yokin saiken) and ordinary savings accounts (通常貯金債権 - tsūjō chokin saiken) belonging to the deceased are not automatically divided among heirs. Instead, they become part of the estate subject to formal division.

One of the reasons cited in the 2016 decision was that bank deposits, in their function, are close to cash and, like cash, have little uncertainty in valuation, making them useful for adjustments during estate division.

The 1992 judgment on physical cash can thus be seen as an early step in a broader jurisprudential trend towards prioritizing the practical needs and facilitation of comprehensive estate division. While the 2016 decision also heavily emphasized the specific contractual nature of bank deposits, the functional similarity to cash and the utility in division were acknowledged factors.

The 2018 amendments to the Civil Code, particularly the introduction of Article 909-2 (allowing heirs to make limited withdrawals from the deceased's bank accounts before estate division), also operate on the premise established by these later Supreme Court rulings that such accounts are generally part of the divisible estate.

Even though Y had deposited the physical cash into an account titled "A Estate Administrator Y," the Supreme Court’s 1992 ruling treated the underlying asset as estate cash. The act of depositing it into a clearly designated estate custodial account did not, in itself, alter its character as an asset subject to the collective claims of all heirs through the estate division process, rather than individual, immediate claims.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1992 decision provides a clear rule for the treatment of physical cash found within an inherited estate: it is considered a co-owned asset subject to formal estate division, and individual heirs cannot demand their pro-rata shares before this division is completed. This ruling distinguishes physical cash from the traditional (though now partly revised) treatment of monetary claims against third parties. By keeping cash within the divisible pool, the Court recognized its practical importance in facilitating fair and flexible estate settlements. This judgment, viewed alongside later developments in case law concerning bank deposits, reflects a consistent judicial effort to ensure that the estate division process can effectively address the entirety of a deceased's assets in a manner that best serves equity among heirs.