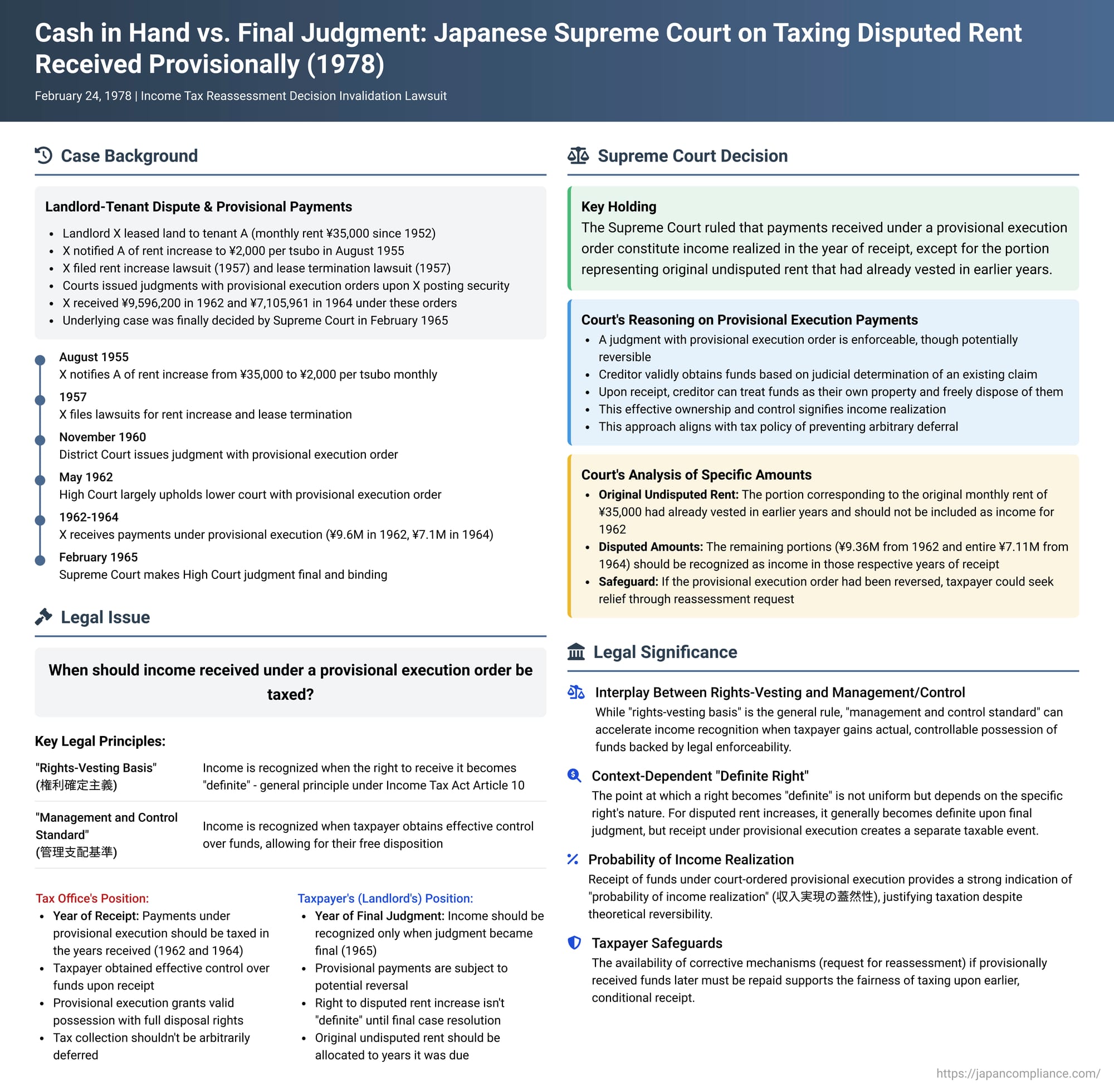

Cash in Hand vs. Final Judgment: Japanese Supreme Court on Taxing Disputed Rent Received Provisionally

Date of Judgment: February 24, 1978

Case Name: Income Tax Reassessment Decision, etc. Invalidation Lawsuit (昭和50年(行ツ)第123号)

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

In a significant ruling on February 24, 1978, the Supreme Court of Japan addressed a complex issue concerning the timing of income recognition for tax purposes. The case involved a landlord who received payments for disputed rent increases and post-termination damages from a tenant under a "provisional execution order" (仮執行宣言 - kari shikkō sengen) while the underlying court judgment was still under appeal. The Supreme Court's decision clarified the interplay between the "rights-vesting basis" (kenri kakutei shugi)—the general principle for income recognition—and the "management and control standard" (kanri shihai kijun), ultimately holding that such provisionally received funds constitute taxable income in the year of receipt.

The Landlord-Tenant Dispute and Provisional Payments

The plaintiff and appellee, X (the landlord), had been leasing land ("the subject land") to a tenant, A. The rent had been ¥35,000 per month since 1952. In August 1955, X notified A of an intent to increase the rent to ¥2,000 per tsubo (a unit of area) per month, effective September 1955. Subsequently, on January 8, 1957, X filed a lawsuit in the Sendai District Court seeking payment of the increased rent. Furthermore, on October 6, 1957, X declared the lease agreement terminated due to A's non-payment of rent and, on October 7, 1957, filed another lawsuit for the removal of buildings from the land, vacation of the land, and payment of damages equivalent to rent.

In the ensuing litigation concerning the rent and eviction (referred to as the "separate case"):

- The Sendai District Court, on November 18, 1960, ordered A to remove the buildings, vacate the land, and pay overdue rent and damages. Crucially, this judgment included a provisional execution order, conditional on X providing security.

- A appealed to the Sendai High Court. On May 28, 1962, the High Court largely upheld the lower court, confirming that the rent was increased (to ¥131,066.25 per month effective September 1955), the lease was terminated as of October 6, 1957, and specified amounts of damages equivalent to rent were due post-termination. This High Court judgment also carried a provisional execution order, conditional on X posting security of ¥1.98 million ("the separate case second instance judgment").

- A further appealed to the Supreme Court, which ultimately dismissed A's appeal on February 19, 1965, making the High Court's judgment final and binding.

While A's appeal in the separate case was still pending before the Supreme Court, X received payments from A under the provisional execution order of the High Court:

- During 1962, X received ¥9,596,200.

- During 1964, X received ¥7,105,961.

These amounts (collectively "the subject amounts") were applied towards the satisfaction of the claims recognized in the separate case second instance judgment.

The head of the tax office (Y, the appellant in the Supreme Court tax case) determined that these amounts received by X should be recognized as income in the respective years of receipt (1962 and 1964). Accordingly, Y issued corrective income tax assessments and underpayment penalties for those years.

X challenged these tax assessments. The Sendai High Court, in the tax litigation, ruled in favor of X, overturning a first instance decision that had upheld the tax office. The High Court reasoned that payments received under a provisional execution order were merely provisional and subject to reversal if the main judgment was overturned on final appeal. Therefore, it concluded, the right to such income could not be considered "definite" (kakutei) at the time of payment. It held that the portion of the payments corresponding to the original, undisputed rent should be attributed to the income of the years those original rents were due, while the remainder (related to the disputed rent increase and damages) should be recognized as income only in 1965, the year the separate case judgment became final. The tax office (Y) appealed this High Court decision to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Principles: "Rights-Vesting" vs. "Management and Control"

The Supreme Court's decision delved into the fundamental principles of income recognition timing under the old Income Tax Act (the law applicable at the time).

- The Rights-Vesting Basis (Kenri Kakutei Shugi): The Court affirmed that the old Income Tax Act, by referring to the "amount to be received" (収入すべき金額 - shūnyū subeki kingaku) in Article 10, paragraph 1, adopted the "rights-vesting basis" as the general principle for income recognition. This means that income is deemed to be realized and becomes taxable in the year the right to receive that income becomes "definite," even if the cash has not yet been actually received.

- Determining When a Right Becomes "Definite": The Court noted that the precise timing when a right becomes "definite" must be determined by considering the specific characteristics of the right in question. For claims concerning increased rent that are disputed by the tenant, the right to the increased portion is generally considered to become definite when a court judgment recognizing the existence of that claim becomes final and binding. This is because, during the dispute, both the legitimacy of the rent increase and its exact amount are uncertain, making it unreasonable to compel the taxpayer to report and pay tax on it, or for the tax authority to independently determine it. The same logic applies to disputed claims for damages equivalent to rent after lease termination.

- The Management and Control Standard (Kanri Shihai Kijun) as an Exception: The Court then introduced a crucial qualifier. It observed that the rights-vesting basis was adopted partly for tax policy reasons – to prevent taxpayers from arbitrarily deferring taxation by delaying actual receipt of income and to ensure fairness in taxation. However, it reasoned that if, even while a claim (like one for increased rent or post-termination damages) is still being contested, the taxpayer actually receives the funds and a situation arises where income realization can be deemed to have occurred, then the income should be calculated for the year of actual receipt. This is often referred to as the "management and control standard."

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Receipt under Provisional Execution is Realization

Applying these principles, the Supreme Court held that payments received under a provisional execution order constitute income realized in the year of receipt.

The Court's specific reasoning was as follows:

- Nature of Provisional Execution Payments: A judgment with a provisional execution order, while potentially subject to reversal or modification by a higher court, is nonetheless an enforceable judgment. Payments made under such an order, though conditionally reversible, mean the creditor (X) validly obtains the funds based on a judicial determination of an existing, albeit not yet absolutely final, claim.

- Control and Disposition of Funds: Once the creditor receives these funds, they can treat them as their own property and freely dispose of them. This effective ownership and control signify that income has been realized.

- Consistency with Tax Policy: Recognizing income upon such receipt, even if the underlying legal right is not absolutely final, aligns with the tax policy rationale of preventing arbitrary deferral and ensuring fairness.

- Safeguard through Corrective Measures: The Court also pointed out that this approach does not lead to undue hardship for the taxpayer. If the provisional execution order or the main judgment is subsequently overturned or modified by a higher court, resulting in the creditor having to repay the provisionally received amounts, the income corresponding to the repaid portion is deemed not to have arisen in the original year of receipt (as per Article 10-6, paragraph 1 of the old Income Tax Act). The taxpayer can then seek relief through a request for reassessment (under Article 27-2 of the old Income Tax Act).

Applying this to the specifics of X's case, the Supreme Court determined:

- The portion of the payments received by X in 1962 that corresponded to the original, undisputed monthly rent of ¥35,000 had already vested in earlier years when those rent installments were initially due. This amount (¥236,774.20 as recalculated by the Supreme Court in its judgment ) should not be included as income for 1962.

- The remaining portion of the funds received in 1962 (¥9,359,425 after deducting the aforementioned original rent portion) and the entirety of the funds received in 1964 (¥7,105,961) – all of which pertained to the disputed rent increase and post-termination damages – should be recognized as income in those respective years of receipt, as they were received under the provisional execution order.

The Supreme Court, therefore, overturned the High Court's decision (in the tax case) and largely reinstated the tax office's approach, albeit with an adjustment for the previously vested original rent amounts.

Key Takeaways and Analysis

The Supreme Court's 1978 judgment is a seminal decision in Japanese tax law concerning the timing of income recognition.

- Interplay of "Rights-Vesting" and "Management and Control" Standards: The case clearly illustrates how these two fundamental principles interact. While the "rights-vesting basis" is the general rule, the "management and control standard" can effectively accelerate income recognition if the taxpayer gains actual, controllable possession of funds, particularly when this possession is backed by some form of legal enforceability, such as a provisional execution order.

- "Definite Right" is Context-Dependent: The Supreme Court acknowledged that the point at which a right becomes "definite" is not a one-size-fits-all concept but depends on the nature of the specific right. Its pronouncement that disputed rent increase claims generally become definite upon final judgment is specific to that context and not a universal definition applicable to all types of income.

- "Probability of Income Realization": Legal commentators suggest that an underlying factor for applying the management and control standard is the "probability of income realization" (shūnyū jitsugen no gaizensei). In this case, receiving funds under a court order that, although provisional, has granted enforceability, provides a strong indication of this probability. The fact that the payment was not purely voluntary but made under the duress of a provisionally enforceable judgment appears significant.

- Taxpayer Safeguards: The availability of corrective mechanisms, such as a request for reassessment if provisionally received funds later have to be repaid, is an important practical consideration that supports the fairness of recognizing income upon earlier, albeit conditional, receipt.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's ruling in this 1978 case provided crucial clarification on the complex issue of income recognition timing for disputed claims, especially when payments are made under provisional court orders. It established that once a taxpayer obtains effective possession and control over funds, allowing for their free disposition, income is generally considered realized for tax purposes, even if the underlying legal right is not yet absolutely final and irreversible. This decision balances the foundational "rights-vesting principle" with the economic reality of benefit received, ensuring that income is taxed in a timely manner while also providing avenues for correction if circumstances later change. It remains a key precedent in understanding the nuanced application of income timing rules in Japanese taxation.