Carbon Copies and Handwritten Wills: A Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on the "Autograph" Requirement

Date of Judgment: October 19, 1993 (Heisei 5)

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench, Case No. Heisei 4 (o) No. 818 (Claim for Confirmation of Will Invalidity)

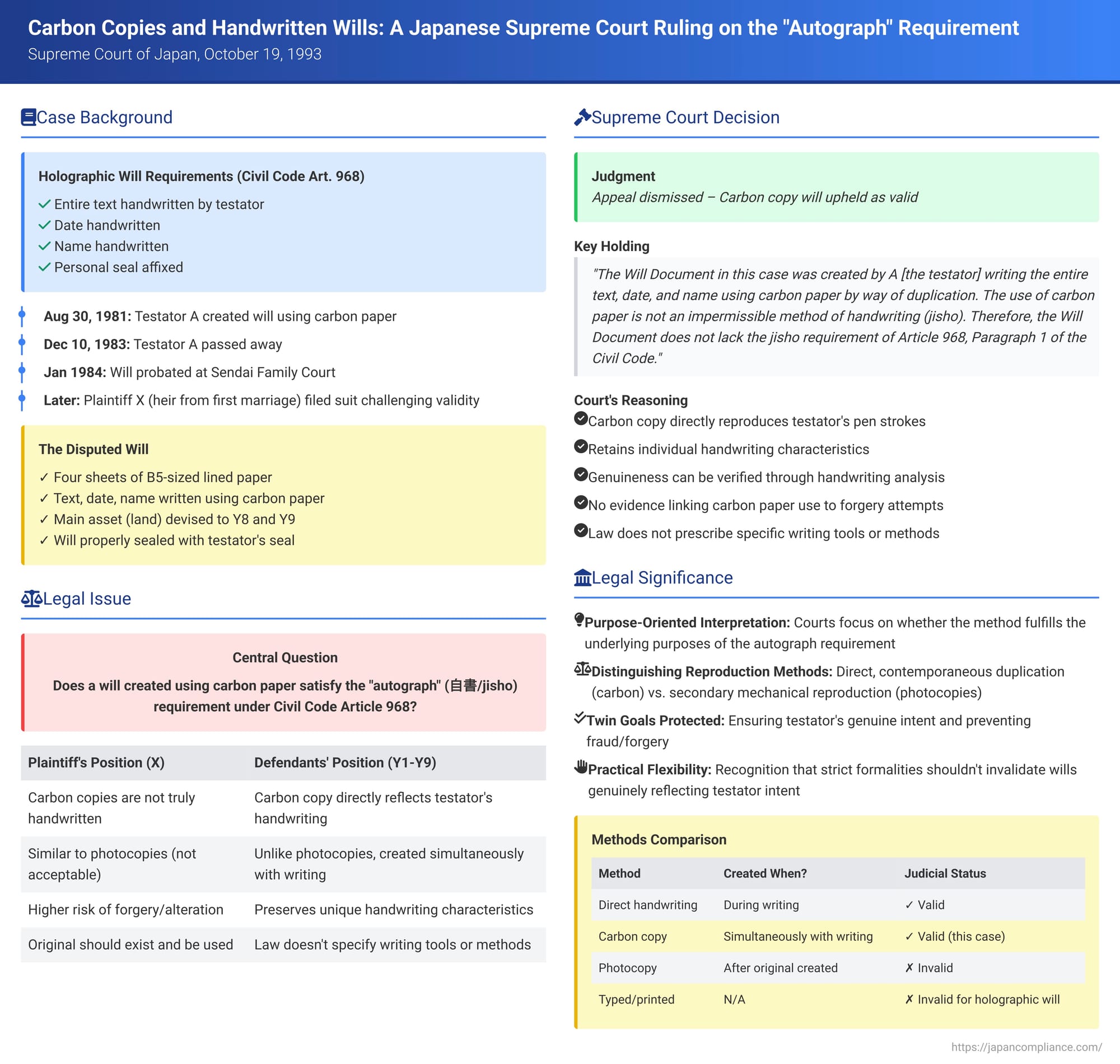

Holographic wills (自筆証書遺言 - jihitsu shōsho igon), which are wills entirely handwritten by the testator, represent a common and accessible method for individuals in Japan to stipulate the distribution of their estate. To ensure their authenticity and prevent fraud, Article 968, Paragraph 1 of the Japanese Civil Code imposes strict formal requirements: the testator must handwrite the entire text, the date, and their name, and affix their personal seal. A significant question that arose before the Supreme Court in 1993 was whether a will created using carbon paper to produce a duplicate of the handwritten portions satisfies the crucial "autograph" (自書 - jisho, meaning "handwritten by oneself") requirement.

Facts of the Case: A Carbon-Copied Will and a Family Dispute

The case involved the estate of A, who passed away on December 10, 1983.

- The Testator and His Family: A had a complex family structure. His legal heirs included:

- X (Haruo AR in the judgment, the plaintiff/appellant), a child from A's first marriage to the deceased B.

- Y1 (Hanako AR in the judgment), A's second wife.

- Y2 and Y3, other children from A's first marriage.

- Y4 through Y8, children from A's marriage to Y1.

- Y9 (Matsuko AR et al. in the judgment, along with Y1 and others, were the defendants/appellees), who was Y8's husband and had been adopted by both A and Y1.

There were a total of ten heirs.

- The Will in Question: A left a holographic will dated August 30, 1981. This will primarily devised A's main asset, a parcel of land, to Y8 and Y9. The will underwent probate proceedings at the Sendai Family Court, Kesennuma Branch, in January 1984.

- Method of the Will's Creation: The will document itself consisted of four sheets of B5-sized lined paper, bound together. Crucially, the text, date, and the testator's name on these sheets were written using carbon paper, creating a duplicate impression. (A secondary issue, ultimately rejected by all courts and not the focus of this analysis, was that the fourth sheet was styled as a will in Y9's name, leading to a claim that it was an impermissible joint will under Article 975 of the Civil Code).

- The Legal Challenge by Heir X: X, one of A's children from his first marriage, filed a lawsuit to have the will declared invalid. X raised several arguments, but the two central ones were:

- Handwriting Authenticity: X alleged that there were unnatural aspects to the handwriting in the will, questioning whether A had personally handwritten the "entire text" as mandated by law.

- Carbon Copy as "Autograph": X contended that a document created using carbon paper to produce a duplicate does not meet the "autograph" (jisho) requirement of Article 968, Paragraph 1 of the Civil Code.

- Lower Court Rulings Upholding the Will:

- First Instance Court: This court dismissed X's claims and upheld the will's validity.

- On the issue of handwriting authenticity (Claim 1), the court considered not only the appearance of the handwriting itself but also the surrounding family circumstances. It noted that X and other children from A's first marriage had moved away, and A lacked a successor. Y8 and Y9 had subsequently moved from Tokyo to live with A and Y1 around September 1980, with Y9 being formally adopted by A and Y1 in October 1980, positioning them as successors. Considering these factors, the court found it plausible that A had indeed handwritten the entire will.

- On the carbon copy issue (Claim 2), the court found no evidence suggesting that the use of carbon paper was linked to any attempt at forgery. It reasoned that the law does not prescribe specific methods or tools for handwriting a will. Since a carbon copy directly reproduces the testator's pen strokes and retains their individual handwriting characteristics, genuineness can be relatively easily determined through handwriting analysis. The court also opined that the risk of fraudulent alteration to a carbon copy was not particularly high. Therefore, it concluded that a will created using carbon paper can satisfy the "autograph" requirement.

- High Court (Original Appeal): The High Court also dismissed X's appeal, affirming the will's validity.

- Regarding Claim 1, it concurred that given the family dynamics (Y8 and Y9 becoming designated successors), A devising significant property to them was not inherently unnatural.

- Regarding Claim 2, it reaffirmed the first instance court's view: even if created with carbon paper, the testator's handwriting characteristics are preserved, allowing for verification by handwriting experts, and the risk of forgery is not significantly elevated. Thus, a carbon copy can qualify as "autograph."

- First Instance Court: This court dismissed X's claims and upheld the will's validity.

- X's Appeal to the Supreme Court: X appealed to the Supreme Court, largely reiterating the previous arguments. Concerning the carbon copy issue, X drew an analogy to photocopies, which are generally not accepted as "autograph" for holographic wills. X argued that carbon copies, like photocopies, can be easily produced by tracing an original document. This, X contended, could result in handwriting that mimics the stroke and character formation of an original but lacks the natural variations in pen pressure and flow, making it very difficult to ascertain true authenticity and increasing the risk of forgery. X also suggested that if a carbon copy will exists, an original (top sheet) likely also exists, meaning that disallowing carbon copies as valid wills would impose no undue hardship on testators, who could simply use the original.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Carbon Copy Method Deemed Permissible

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal, thereby upholding the validity of the carbon-copied holographic will.

The Court's reasoning on the two main points was concise:

- On Handwriting Authenticity: The Supreme Court affirmed the High Court's factual determination that A had indeed handwritten the will. It found no error in the High Court's assessment of the evidence leading to this conclusion.

- On Carbon Copy as "Autograph" (Jisho): Regarding the central legal question, the Supreme Court stated:

"The Will Document in this case was created by A [the testator] writing the entire text, date, and name using carbon paper by way of duplication. The use of carbon paper is not an impermissible method of handwriting (jisho). Therefore, the Will Document does not lack the jisho requirement of Article 968, Paragraph 1 of the Civil Code."

Legal Principles and Significance

This 1993 Supreme Court decision provided important clarification on what constitutes "autograph" handwriting for the purpose of holographic wills in Japan.

- Purpose of the "Autograph" Requirement: The stringent requirement under Articles 960 and 968(1) of the Civil Code that a holographic will be entirely handwritten by the testator (along with the date, name, and seal) serves two primary functions:

- To ensure the genuineness of the testator's intent regarding the disposition of their property upon death.

- To prevent forgery, alteration, and disputes by making the document uniquely attributable to the testator through their distinct handwriting.

As a Supreme Court decision from Showa 62 (1987) (cited in the PDF commentary) articulated, the purpose of requiring the testator to handwrite the full text, date, and name is to clarify the will's content, ensure the certainty of the testator's intent, and make it easy to identify the testator, thereby preventing disputes and fraud.

- Defining "Autograph" (Jisho) in Context:

- The term "autograph" or "handwriting by oneself" (jisho) is fundamentally contrasted with having the will written by another person (代書 - daisho, or dictation). Other forms of wills in Japan, such as notarized wills (公正証書遺言 - kōsei shōsho igon) or secret wills (秘密証書遺言 - himitsu shōsho igon), allow for the text to be written by someone other than the testator (e.g., a notary or a third party) precisely because these alternative methods involve other formal safeguards, like the presence of notaries and witnesses, to ensure authenticity and prevent fraud.

- Whether a copy produced by the testator's own physical act of writing qualifies as "autograph" is not immediately obvious from the term itself. The PDF commentary suggests that this determination must be made by considering the underlying purpose of the autograph requirement.

- Why a Carbon Copy Can Fulfill the "Autograph" Requirement: The Supreme Court's affirmation of the lower courts' reasoning rests on several key points:

- Direct Reflection of Penmanship: A carbon copy is created simultaneously with an original (the top sheet) or another carbon copy through the direct physical pressure and movement of the testator's hand using a writing instrument. It is not a subsequent mechanical reproduction like a photocopy.

- Preservation of Handwriting Characteristics: Because it is a direct impression of the testator's writing act, a carbon copy retains the individual and unique characteristics of their handwriting—stroke formation, style, etc.

- Verifiability: These preserved handwriting characteristics allow for graphological analysis (handwriting expertise) to determine the authenticity of the will, i.e., whether it was indeed written by the testator.

- Risk of Forgery/Alteration: The courts in this case did not find that the use of carbon paper inherently presented a significantly higher risk of forgery or undetectable alteration compared to a will written directly with ink on a single sheet. In fact, some might argue that altering a carbon impression without leaving traces could be more difficult than altering an ink original.

- Distinction from Photocopies and Other Mechanical Reproductions: The appellant (X) attempted to equate carbon copies with photocopies. However, there is a critical distinction. A photocopy is a secondary, mechanical reproduction of an existing document. It does not involve the testator's contemporaneous physical act of forming the letters and words. A carbon copy, in contrast, is a direct, contemporaneous result of the testator's own writing process.

- Focus on Ensuring Testator's Intent and Preventing Fraud: Ultimately, the courts concluded that if a carbon-copied document reliably reproduces the testator's own handwriting and there are no other suspicious circumstances, the core legislative aims of ensuring the testator's genuine intent and preventing fraud can still be adequately met.

- Practical Considerations: Disallowing carbon copies as a valid method of "handwriting" could potentially lead to the invalidation of wills genuinely intended by testators who might have used this method for practical reasons, such as creating a simultaneous duplicate for their records.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1993 decision provides valuable guidance by confirming that a holographic will created using carbon paper can satisfy the "autograph" (jisho) requirement of Article 968, Paragraph 1 of the Civil Code. The ruling emphasizes that as long as the method used results in a document that directly and verifiably reflects the testator's own handwriting and thereby serves the underlying purposes of the autograph requirement—ensuring authenticity and preventing fraud—it can be deemed permissible. This decision reflects a practical approach, distinguishing between direct manual duplication methods like carbon copying and indirect mechanical reproductions, in the context of Japan's strict formalities for holographic wills.