Capturing the Scene: Admissibility of Crime Scene Photographs in Japanese Law

Date of Decision: December 21, 1984

Introduction

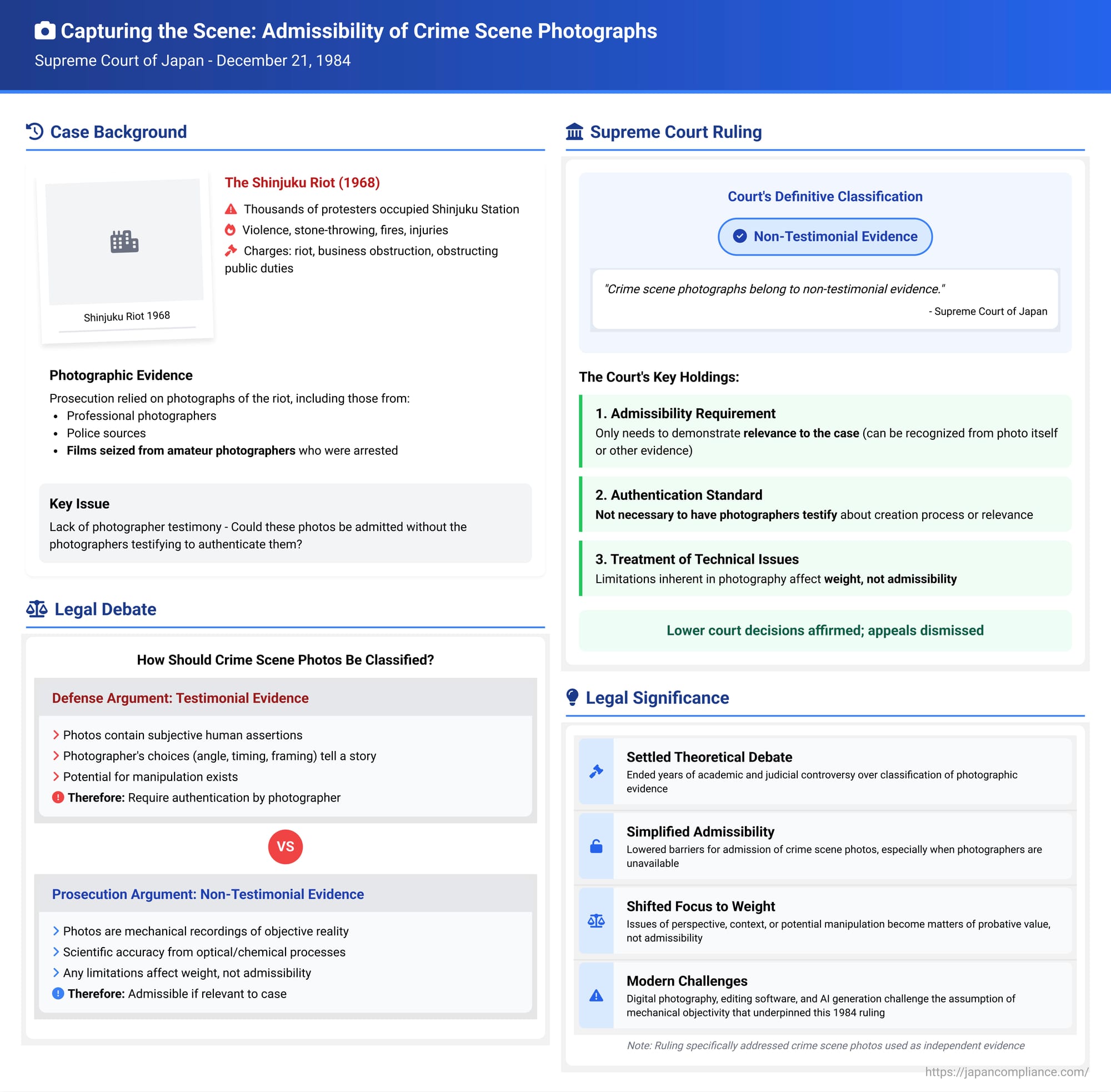

Photographs often play a pivotal role in criminal trials, offering a visual record of crime scenes, evidence, or events. From stark images of a crime scene to photos depicting the progression of a public disturbance, such visual evidence can profoundly impact fact-finding. However, the legal classification and admissibility of photographs have historically been subjects of debate. Are photographs inherently objective, mechanical recordings (non-testimonial evidence), or do they carry an element of human assertion (testimonial evidence) requiring stricter rules for admission, similar to witness statements? A significant decision by the Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench, on December 21, 1984, arising from the turbulent Shinjuku Riot case, provided a clear answer regarding the admissibility of crime scene photographs used as independent evidence.

Factual Background: The Shinjuku Riot and Photographic Evidence

The case stemmed from the "Shinjuku Riot" (新宿騒乱事件 - Shinjuku sōran jiken), a large-scale disturbance that occurred on October 21, 1968, during the "International Anti-War Day" protests. Thousands of students and other individuals engaged in demonstrations around Shinjuku Station in Tokyo, eventually occupying the station premises. The ensuing events involved acts of violence, including throwing stones, setting fires, injuring numerous police officers, and damaging train and station facilities, causing widespread chaos and fear.

Several individuals, including the appellants in this case, were charged with offenses under the Penal Code, including leading or assisting a riot (騒擾指揮・助勢 - sōjō shiki/josei), forcible obstruction of business, and obstruction of the performance of public duties.

During the trial, a key evidentiary issue involved numerous photographs depicting the events within and around Shinjuku Station during the riot. These photographs were crucial for the prosecution to establish the nature and scale of the disturbance and the actions of the participants. Notably, some of these photographs originated from film seized by police from amateur photographers who were arrested at the scene. The police subsequently developed and printed these films.

The defense contested the admissibility of these "crime scene photographs" (genba shashin). They argued, among other things, that photographs should be treated as testimonial evidence, akin to statements. Consequently, they contended that admitting the photos required proper authentication, specifically through the testimony of the photographers regarding the circumstances of the shooting (when, where, what), the development process, and the relevance to the case. They highlighted the potential for manipulation or distortion in photographs and argued that without the photographer's testimony confirming authenticity and context, the photos lacked the necessary foundation for admissibility. Some photos were particularly challenged because the police officer involved in processing them invoked official secrecy regarding certain details during testimony.

The first-instance court (Tokyo District Court) and the High Court (Tokyo High Court) rejected these arguments. They held that crime scene photographs are essentially mechanical recordings of objective reality. The High Court explicitly stated that photographs are fundamentally different from testimonial evidence due to their scientific accuracy derived from optical and chemical processes. It classified them as non-testimonial evidence (hi-kyōjutsu shōko), admissible as long as their relevance to the case could be established. The High Court further reasoned that limitations inherent in photography (like color/contrast variations, fixed perspectives, lack of continuous recording) affect the weight or probative value of the photos, not their fundamental admissibility. The defendants appealed this point, among others, to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Photographs as Non-Testimonial Evidence

The Supreme Court dismissed the appeals. While finding most arguments to be improper grounds for appeal (e.g., mere assertions of legal violation or factual error), it specifically addressed the issue of crime scene photographs in a sua sponte (on its own initiative) statement within its reasoning.

The Court decisively resolved the long-standing debate, aligning itself with the High Court's view:

- Classification: "So-called crime scene photographs depicting the circumstances of the offense, etc., belong to non-testimonial evidence."

- Admissibility Requirement: "As long as relevance to the case (事件との関連性 - jiken tono kanrensei) can be recognized from the photograph itself or other evidence, they possess evidentiary capacity."

- Authentication: "To adopt these as evidence, it is not necessarily required to have the photographer(s) testify about the creation process of the scene photographs or their relevance to the case."

This ruling clearly established that, for the purpose of admissibility as independent evidence, crime scene photographs are treated as objective recordings, not as statements requiring the stringent authentication typically associated with testimonial evidence under hearsay rules (like those in Article 321 of the Code of Criminal Procedure).

Broader Context: Defining Riot

While the main evidentiary focus was on photographs, the decision also touched upon the legal definition of the crime of riot (騒擾罪 - sōjōzai) under Article 106 of the Penal Code, affirming the lower courts' interpretations:

- Multiple Groups, Single Riot: Even if composed of different groups acting at slightly different times and places, a series of violent acts can constitute a single riot if the later acts are inspired by, adopt, and continue the earlier violence in close temporal and spatial proximity, demonstrating an overall shared intent.

- Disturbance in "One Locality": The required disturbance of public peace must occur in "one locality" (ichi chihō). The Court clarified that "locality" is not defined merely by geographic size or population but involves considering the area's social importance, public usage patterns, workforce activities (dynamic and functional factors), and whether the disturbance caused fear beyond the immediate vicinity. Shinjuku Station, a major transportation hub, and its surroundings were deemed such a locality.

Analysis and Implications: Settling a Debate, Facing New Challenges

The 1984 Supreme Court decision was highly significant for its clear adoption of the non-testimonial evidence theory for crime scene photographs used independently.

- Resolution of Theoretical Debate: It settled the long-standing academic and judicial debate in favor of treating photographs primarily as mechanical recordings rather than statements. This view emphasizes the scientific process of photography as producing an objective trace of reality, distinct from the fallible human processes of perception, memory, and narration involved in testimony.

- Simplified Admissibility Standard: By setting "relevance" as the primary threshold and stating that photographer testimony is not mandatory, the ruling simplified the process for admitting crime scene photos. This is particularly important in situations like the Shinjuku Riot case, where photos might come from various sources (including amateurs, confiscated film, or unknown photographers) whose testimony might be difficult or impossible to obtain. Relevance could potentially be established through the content of the photo itself (e.g., recognizable landmarks, time indicators) or through other corroborating evidence.

- Focus Shifts to Weight: The decision effectively shifts the focus from admissibility challenges based on lack of photographer testimony to arguments about the weight or probative value of the photograph. Issues like potential distortion, limited perspective, lack of context, or possibility of manipulation become matters for the fact-finder to consider when evaluating how much importance to give the photographic evidence, rather than bars to its admission.

- Criticisms Remain: Despite becoming the prevailing view, the non-testimonial theory is not without criticism. Some argue that the photographer's choices (framing, timing, lens selection) inevitably introduce a subjective element, akin to a statement about the scene. Others point out that allowing relevance to be judged "from the photo itself" risks conflating the initial admissibility question (is it relevant?) with the ultimate assessment of its value (what does it prove?).

- The Digital Age Challenge: A crucial point, highlighted in later commentary (like Prof. Kurosawa's), is that this 1984 decision was grounded in the era of film photography. The advent of digital photography, sophisticated editing software, and now AI image generation tools dramatically increases the ease and potential undetectability of manipulation. This technological shift fundamentally challenges the assumption of inherent mechanical objectivity and accuracy that underpinned the 1984 ruling. Does the non-testimonial classification and the relaxed authentication standard still hold adequately protective in an age where photographic "reality" can be convincingly fabricated? This leads some contemporary scholars to argue for revisiting the issue, perhaps demanding stronger authentication even for photographic evidence.

- Scope Limitations: It's important to note the decision's specific context: crime scene photographs used as independent evidence. The ruling does not necessarily dictate the treatment of photographs used differently, such as reenactment photos meant to illustrate testimony (addressed in the 2005 decision discussed previously) or photos embedded within expert reports.

Conclusion

The 1984 Supreme Court decision in the Shinjuku Riot case provided a landmark clarification in Japanese evidence law, classifying crime scene photographs as non-testimonial evidence admissible upon a showing of relevance, without mandating testimony from the photographer. This ruling streamlined the admission of crucial visual evidence, particularly from complex events with multiple sources. However, while it settled the debate based on the technology of its time, the digital revolution and the rise of sophisticated image manipulation techniques pose significant new challenges to the assumptions underlying this precedent. The legal framework governing digital evidence, including photographs, continues to evolve as courts and legislators grapple with ensuring both the admissibility of relevant information and the reliability of evidence in the modern technological landscape.